Case 3 Kering SA: Probing the Performance Gap with LVMH 461

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OPTIMAL VALUE R Eurozone Value Equity ISIN FR0012144590 MONTHLY REPORT AUGUST 31, 2021

MANDARINE OPTIMAL VALUE R Eurozone Value Equity ISIN FR0012144590 MONTHLY REPORT AUGUST 31, 2021 Risk profile 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Mandarine Optimal Value selects eurozone companies with two specific characteristics: stocks that are undervalued by the market and offer an improving financial and extra- financial outlook (positive momentum). +2.7% +24.2% 16.9% Performance Performance Volatility 1 month YTD 1 year PERFORMANCES AND RISKS The data presented relates to past periods, past performance is not an indicator of future results. Bench. Bench. Bench. +2.6% +20.3% 16.9% Statistical indicators are calculated on a weekly basis. Benchmark: EuroStoxx Large NR Evolution since inception 162.13EUR Fund Bench. Net asset value 80% Yohan Florian SALLERON ALLAIN 60% Even if some fears persist regarding the pace of future growth (thereby favouring stocks with 40% generally defensive profiles over the month), the eurozone stock markets pursued their rebounds, 20% consequently showing solid annual gains. 0% As could be expected, the best contributors to the fund’s performance over the month included -20% healthcare (Merck, Eurofins scientific) and public 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 services (Verbund). Our luxury goods stocks (LVMH, Moncler and Kering) suffered in August due to Chinese Annual performances statements evoking the idea of a better distribution of wealth in China. Fund Bench. 30% Despite the rather cyclical bias in our portfolio, +26.5 +24.2 which we are maintaining due to these stocks’ +20.3 +16.3 good financial momentum (which is not 15% +12.3 +10.8 weakening), the fund nevertheless succeeded in +6.2 slightly outperforming its benchmark index over +4.0 the month, thereby adding to its cumulative 0% outperformance since the beginning of the year. -

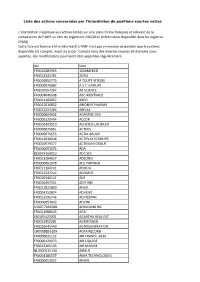

Liste Des Actions Concernées Par L'interdiction De Positions Courtes Nettes

Liste des actions concernées par l'interdiction de positions courtes nettes L’interdiction s’applique aux actions listées sur une plate-forme française et relevant de la compétence de l’AMF au titre du règlement 236/2012 (information disponible dans les registres ESMA). Cette liste est fournie à titre informatif. L'AMF n'est pas en mesure de garantir que le contenu disponible est complet, exact ou à jour. Compte tenu des diverses sources de données sous- jacentes, des modifications pourraient être apportées régulièrement. Isin Nom FR0010285965 1000MERCIS FR0013341781 2CRSI FR0010050773 A TOUTE VITESSE FR0000076887 A.S.T. GROUPE FR0010557264 AB SCIENCE FR0004040608 ABC ARBITRAGE FR0013185857 ABEO FR0012616852 ABIONYX PHARMA FR0012333284 ABIVAX FR0000064602 ACANTHE DEV. FR0000120404 ACCOR FR0010493510 ACHETER-LOUER.FR FR0000076861 ACTEOS FR0000076655 ACTIA GROUP FR0011038348 ACTIPLAY (GROUPE) FR0010979377 ACTIVIUM GROUP FR0000053076 ADA BE0974269012 ADC SIIC FR0013284627 ADEUNIS FR0000062978 ADL PARTNER FR0011184241 ADOCIA FR0013247244 ADOMOS FR0010340141 ADP FR0010457531 ADTHINK FR0012821890 ADUX FR0004152874 ADVENIS FR0013296746 ADVICENNE FR0000053043 ADVINI US00774B2088 AERKOMM INC FR0011908045 AG3I ES0105422002 AGARTHA REAL EST FR0013452281 AGRIPOWER FR0010641449 AGROGENERATION CH0008853209 AGTA RECORD FR0000031122 AIR FRANCE -KLM FR0000120073 AIR LIQUIDE FR0013285103 AIR MARINE NL0000235190 AIRBUS FR0004180537 AKKA TECHNOLOGIES FR0000053027 AKWEL FR0000060402 ALBIOMA FR0013258662 ALD FR0000054652 ALES GROUPE FR0000053324 ALPES (COMPAGNIE) -

Fashioning Gender Fashioning Gender

FASHIONING GENDER FASHIONING GENDER: A CASE STUDY OF THE FASHION INDUSTRY BY ALLYSON STOKES, B.A.(H), M.A. A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY AND THE SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES OF MCMASTER UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY c Copyright by Allyson Stokes, August 2013 All Rights Reserved Doctor of Philosophy (2013) McMaster University (Sociology) Hamilton, Ontario, Canada TITLE: Fashioning Gender: A Case Study of the Fashion Industry AUTHOR: Allyson Stokes BA.H., MA SUPERVISOR: Dr. Tina Fetner NUMBER OF PAGES: xii, 169 ii For Johnny. iii Abstract This dissertation uses the case of the fashion industry to explore gender inequality in cre- ative cultural work. Data come from 63 in-depth interviews, media texts, labor market statistics, and observation at Toronto’s fashion week. The three articles comprising this sandwich thesis address: (1) processes through which femininity and feminized labor are devalued; (2) the gendered distribution of symbolic capital among fashion designers; and (3) the gendered organization of the fashion industry and the “ideal creative worker.” In chapter two, I apply devaluation theory to the fashion industry in Canada. This chap- ter makes two contributions to literature on the devaluation of femininity and “women’s work.” First, while devaluation is typically used to explain the gender wage gap, I also address symbolic aspects of devaluation related to respect, prestige, and interpretations of worth. Second, this paper shows that processes of devaluation vary and are heavily shaped by the context in which work is performed. I address five processes of devaluation in fash- ion: (1) trivialization, (2) the privileging of men and masculinity, (3) the production of a smokescreen of glamour, (4) the use of free labor and “free stuff,” and (5) the construction of symbolic boundaries between “work horses” and “show ponies.” In chapter three, I use media analysis to investigate male advantage in the predomi- nantly female field of fashion design. -

BIODIVERSITY STRATEGY Bending the Curve on Biodiversity Loss KERING BIODIVERSITY STRATEGY

BIODIVERSITY STRATEGY Bending the Curve on Biodiversity Loss KERING BIODIVERSITY STRATEGY FOREWORD “How we solve the ongoing environmental crisis is likely the biggest challenge facing our generation. Given the scale of biodiversity loss sweeping the planet, we must take bold action. As businesses, we need to safeguard nature within our own supply chains, as well as champion transformative actions far beyond them to ensure that humanity operates within planetary boundaries. At Kering, our Houses’ products begin their lives in farms, fields, forests and other ecosystems around the world. The careful stewardship of these landscapes is fundamental to our continued success, and also linked to our responsibility on a broader global scale. With Kering’s biodiversity strategy, we are proud to put forth concrete targets to play our part in bending the curve on biodiversity loss, and helping to chart a course for our industry.” François-Henri Pinault Chief Executive Officer, Kering 1 KERING BIODIVERSITY STRATEGY CONTENTS Our Planet In Peril – p.03 Our Commitment – p.04 A Paradigm Shift – p.05 Taking Stock of Progress at Kering – p.06 Taking Action: Aligning To The Science Based Targets Network – p.07 Value Chain Mapping & Materiality Assessments – p.08 Environmental Profit & Loss (EP&L) Accounting – p.09 The Biodiversity Impact Metric – p.09 The Guiding Framework Stage 1: Avoid – p.10 Stage 2: Reduce – p.13 Stage 3: Restore & Regenerate – p.16 Stage 4: Transform – p.20 Monitoring, Reporting & Verification– p.23 Final Thoughts – p.23 References – p.24 Acknowledgements We wish to thank the many external reviewers who provided critical feedback to strengthen this strategy. -

Of Gucci, Crasi Vira- Le, Collisione Digitale Tra Il Social Del Momento Clubhouse Marchio, Questo Nome, Questa Saga

il primo quotidiano della moda e del lusso Anno XXXII n. 074 Direttore ed editore Direttore MFvenerdì fashion 16 aprile 2021 MF fashion Paolo Panerai - Stefano RoncatoI 16.04.21 CClub-Houselub-House UN LOOK DELLA COLLEZIONE ARIA DI GUCCI ooff GGucciucci DDalal SSavoyavoy a uunn EEdenden lluminosouminoso ddoveove ssii pprenderende iill vvolo.olo. IIll vvideoideo cco-direttoo-diretto ddaa AAlessandrolessandro MMicheleichele e ddaa FFlorialoria SSigismondiigismondi ssperimentaperimenta ppensandoensando aaii 110000 aanninni ddellaella mmaisonaison ddellaella ddoppiaoppia GG,, ssvelandovelando ll’inedito’inedito ddialogoialogo cconon DDemnaemna GGvasaliavasalia ddii BBalenciagaalenciaga o rrilettureiletture ddelel llavoroavoro ddii TTomom FFord.ord. TTrara lluccicanzeuccicanze ddii ccristalli,ristalli, ssartorialeartoriale ssensuale,ensuale, eelementilementi eequestriquestri ffetishetish e rrimandiimandi a HHollywoodollywood ucci gang, Lil Pump canta. Un innocente tailleur si avvicina al- la cam e svela the body of evidence. Glitter, cristalli, ricami, La scritta Balenciaga sulla giacca, le calze con il logo GG. Quei Gdue nomi uniti, che tanto hanno scatenato l’interesse di que- sti giorni alla fine sono comparsi (vedere MFF del 12 aprile). Gucci e Balenciaga, sovrapposti nei ricami e nelle fantasie, in una composizione che farà impazzire i consumatori. Kering ringrazia. Ma ringrazia anche per la collezione Aria che incomincia a svelare i festeggiamenti per i 100 anni della maison Gucci. Un mondo che è andato in scena in quel corto- metraggio co-diretto da Alessandro Michele e da Floria Sigismondi, la regista avantguard e visionaria dei videoclip musicali che aveva già col- laborato con la fashion house della doppia G. E in effetti la musica ha un grande peso, oltre al ritmo diventa una colonna sonora con canzoni che citano la parola Gucci a più riprese, super virale. -

Luxury Swiss Watchmaker Ulysse Nardin Partners with Ocearch, the Leading Scientific Shark Conservation Non-Profit

LUXURY SWISS WATCHMAKER ULYSSE NARDIN PARTNERS WITH OCEARCH, THE LEADING SCIENTIFIC SHARK CONSERVATION NON-PROFIT ULYSSE NARDIN’S ONGOING COMMITMENT TO PROTECT THE WORLD’S OCEANS IS FURTHERED THROUGH THIS PARTNERSHIP WITH OCEARCH WHICH TIRELESSLY STRIVES TO SAVE THE PLANET’S SHARK POPULATION CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD HI RES IMAGERY Miami, Florida – June 29, 2020 – Luxury Swiss watchmaker, ULYSSE NARDIN announces today its partnership and support of the non-profit research organization, OCEARCH. Continuing its commitment to supporting marine research, ULYSSE NARDIN, has teamed up with OCEARCH, a data and scientific driven organization that works collaboratively with researchers and educational institutions to better understand the movement and habits of sharks. As a watch brand with deep ties to the ocean symbolized by the shark, it was only natural for ULYSSE NARDIN to form a partnership with the very organization leading the charge in shark research and conservation. OCEARCH’s urgent mission is to accelerate the ocean’s return to balance and abundance through fearless innovation in scientific research, education, outreach, and policy, using unique collaborations of individuals and organizations in the U.S. and abroad. Their goal is to assist researchers in their work and provide invaluable resources to better understand the shark’s role as apex predator in the ocean’s fragile ecosystem. The art of watching a shark’s migratory movement and the science behind their effect on marine life has been mastered by the OCEARCH team. Their hard-work and dedication to the understanding of sharks piqued the interest of the U.S. president of ULYSSE NARDIN, François-Xavier Hotier, when he joined the brand in 2018. -

Devoir De Vigilance: Reforming Corporate Risk Engagement

Devoir de Vigilance: Reforming Corporate Risk Engagement Copyright © Development International e.V., 2020 ISBN: 978-3-9820398-5-5 Authors: Juan Ignacio Ibañez, LL.M. Chris N. Bayer, PhD Jiahua Xu, PhD Anthony Cooper, J.D. Title: Devoir de Vigilance: Reforming Corporate Risk Engagement Date published: 9 June 2020 Funded by: iPoint-systems GmbH www.ipoint-systems.com 1 “Liberty consists of being able to do anything that does not harm another.” Article 4, Declaration of the Rights of the Man and of the Citizen of 1789, France 2 Executive Summary The objective of this systematic investigation is to gain a better understanding of how the 134 confirmed in-scope corporations are complying with – and implementing – France’s progressive Devoir de Vigilance law (LOI n° 2017-399 du 27 Mars 2017).1 We ask, in particular, what subject companies are doing to identify and mitigate social and environmental risk/impact factors in their operations, as well as for their subsidiaries, suppliers, and subcontractors. This investigation also aims to determine practical steps taken regarding the requirements of the law, i.e. how the corporations subject to the law are meeting these new requirements. Devoir de Vigilance is at the legislative forefront of the business and human rights movement. A few particular features of the law are worth highlighting. Notably, it: ● imposes a duty of vigilance (devoir de vigilance) which consists of a substantial standard of care and mandatory due diligence, as such distinct from a reporting requirement; ● sets a public reporting requirement for the vigilance plan and implementation report (compte rendu) on top of the substantial duty of vigilance; ● strengthens the accountability of parent companies for the actions of subsidiaries; ● encourages subject companies to develop their vigilance plan in association with stakeholders in society; ● imposes civil liability in case of non-compliance; ● allows stakeholders with a legitimate interest to seek injunctive relief in the case of a violation of the law. -

New Concept Stores Anchor Luxury Retail Offerings at the Shoppes At

New concept stores anchor luxury retail offerings at The Shoppes at Marina Bay Sands Brioni, HUGO BOSS and Zara debut unique boutique concepts, enhancing The Shoppes’ existing selection of ready-to-wear fashion Singapore (23 August 2013) - The Shoppes at Marina Bay Sands recently welcomed two brand new concept stores to its fleet of 300-strong retail outlets. German luxury fashion label HUGO BOSS and Zara, one of the largest fashion retailers in the world, unveiled unique boutique concepts for the first time in Singapore last week at Asia’s most premier shopping destination. Adding to The Shoppes’ existing collection of ready-to-wear fashion offerings this September are Balenciaga, Brioni as well as luxury Swiss watchmaker Ulysse Nardin. HUGO BOSS reopens at The Shoppes at Marina Bay Sands with a new line of womenswear HUGO BOSS1 reopens at The Shoppes with a new generation interior design concept and an additional women’s ready-to-wear and accessory line curated by New York-based fashion designer Jason Wu2. Spanning across 3,832 square feet, the new store is bigger than its previous one, and continues to carry menswear by BOSS and BOSS Green. Key elements of the new interior design include black steel grids with light-emitting diode (LED) strips and exquisite fabric wall cladding and magnolia back panel frames paired with black high gloss furniture to create a refined ambience. Furniture with bronze glass elements also sets a sophisticated mood, emphasizing the overall elegance of the store. *** Owned by the Inditex Group, Zara3 presents its new concept store in Singapore for the very first time, offering Women’s, Men’s and Kids’ apparel. -

Press Release 05.06.2021

PRESS RELEASE 05.06.2021 REPURCHASE OF OWN SHARES FOR ALLOCATION TO FREE SHARE GRANT PROGRAMS FOR THE BENEFIT OF EMPLOYEES Within the scope of its share repurchase program authorized by the April 22, 2021 shareholders' meeting (14th resolution), Kering has entrusted an investment service provider to acquire up to 200,000 ordinary Kering shares, representing close to 0.2% of its share capital as at April 15, 2021, no later than June 25, 2021 and subject to market conditions. These shares will be allocated to free share grant programs to some employees. The unit purchase price may not exceed the maximum set by the April 22, 2021 shareholders' meeting. As part of the previous repurchase announced on February 22, 2021 (with a deadline of April 16, 2021), Kering bought back 142,723 of its own shares. About Kering A global Luxury group, Kering manages the development of a series of renowned Houses in Fashion, Leather Goods, Jewelry and Watches: Gucci, Saint Laurent, Bottega Veneta, Balenciaga, Alexander McQueen, Brioni, Boucheron, Pomellato, DoDo, Qeelin, Ulysse Nardin, Girard-Perregaux, as well as Kering Eyewear. By placing creativity at the heart of its strategy, Kering enables its Houses to set new limits in terms of their creative expression while crafting tomorrow’s Luxury in a sustainable and responsible way. We capture these beliefs in our signature: “Empowering Imagination”. In 2020, Kering had over 38,000 employees and revenue of €13.1 billion. Contacts Press Emilie Gargatte +33 (0)1 45 64 61 20 [email protected] Marie de Montreynaud +33 (0)1 45 64 62 53 [email protected] Analysts/investors Claire Roblet +33 (0)1 45 64 61 49 [email protected] Laura Levy +33 (0)1 45 64 60 45 [email protected] www.kering.com Twitter: @KeringGroup LinkedIn: Kering Instagram: @kering_official YouTube: KeringGroup Press release 05.06.2021 1/1 . -

View Annual Report

2016 ANNUAL REPORT CONTENT MESSAGES FROM THE SUPERVISORY BOARD AND THE MANAGEMENT BOARD 02 1 4 Profile of the Group and its Businesses | Financial Report | Statutory Auditors’ Report Financial Communication, Tax Policy on the Consolidated Financial Statements | and Regulatory Environment | Risk Factors 05 Consolidated Financial Statements | 1. Profi le of the Group and its Businesses 07 Statutory Auditors’ Report on 2. Financial Communication, Tax policy and Regulatory Environment 43 the Financial Statements | Statutory 3. Risk Factors 47 Financial Statements 183 Selected key consolidated fi nancial data 184 I - 2016 Financial Report 185 II - Appendix to the Financial Report: Unaudited supplementary fi nancial data 208 2 III - Consolidated Financial Statements for the year ended December 31, 2016 210 Societal, Social and IV - 2016 Statutory Financial Statements 300 Environmental Information 51 1. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Policy 52 2. Key Messages 58 3. Societal, Social and Environmental Indicators 64 4. Verifi cation of Non-Financial Data 101 5 Recent Events | Forecasts | Statutory Auditors’ Report on EBITA forecasts 343 1. Recent Events 344 2. Forecasts 344 3 3. Statutory Auditors’ Report on EBITA forecasts 345 Information about the Company | Corporate Governance | Reports 107 1. General Information about the Company 108 2. Additional Information about the Company 109 3. Corporate Governance 125 6 4. Report by the Chairman of Vivendi’s Supervisory Board Responsibility for Auditing the Financial Statements 347 on Corporate Governance, Internal Audits and Risk 1. Responsibility for Auditing the Financial Statements 348 Management – Fiscal year 2016 172 5. Statutory Auditors’ Report, Prepared in Accordance with Article L.225-235 of the French Commercial Code, on the Report Prepared by the Chairman of the Supervisory Board of Vivendi SA 181 ANNUAL REPORT 2016 ANNUAL REPORT 2016 The Annual Report in English is a translation of the French “Document de référence” provided for information purposes. -

Isis Samuels Swaby CDMG 1111 Digital Media Foundations Professor Tanya Goetz December 20 2017 Study of Logos

Isis Samuels Swaby CDMG 1111 Digital Media Foundations Professor Tanya Goetz December 20 2017 Study of Logos Guccio Gucci created ‘Gucci’ based on his love for leather goods in Florence, Italy in 1921. By 1933, he joined forces with his family to build the business into a larger company and worldwide brand. The designer of the logo of Gucci happened be one of Gucci’s three sons named Aldo Gucci. He joined The House of Gucci in 1933. The logo symbolizes grandeur and authenticity and is seen worldwide. (Ebaqdesign 1) ‘GG’ Type facing in a flip reverse is the Gucci Logo based on Guccio Gucci original namesake. However, it is slightly similar to designer fashion house, Chanel’s Double CC logo. For almost the duration of this time, Gucci has proudly displayed its double-G logo, working to make the emblem a symbol for high-end quality and a proud stamp of the company’s approval. (Logomyway 1) Classic Gucci Ads show the luxury and versatility of the Gucci, designer brand that captures the persona and illusion of design. The class GG Double Locking Type on a belt design, which is the classic logo for Gucci. The newest transitions of the logo has developed into emblem of a woman figure. Source: Logomyway.com ‘The Lady Lock is part of the collection released for Fall/Winter 2013. The signature Gucci logo embossed cappuccio and lock are typically crafted in shiny metal and accompany a collection of handbags that have a rounded, minimalist shape.’ (Yoogi Closet 1) The typeface appears to be Times New Roman and in Uppercase. -

PUMA Relay 2014 Annual Report 2014 Puma Timeline Our Highlights in 2014

PUMA RELAY 2014 Annual Report 2014 PUMA TIMELINE OUR highlights IN 2014 JAN FEB MAR apr maY june julY aUG SEP oct noV DEC evoPOWER Launch “PUMA Lab” Roll-Out World Cup Kit Launch Lexi Thompson’s First Major PUMA Village Closure FIFA World Cup™ in Brazil Arsenal FC Kit Launch “Forever Faster” Campaign Retail Business Relocation Becker OG Release F1-Championship for Hamilton New Global Ambassador Rihanna PUMA introduces its most Together with Foot Locker PUMA reveals the new COBRA PUMA golfer Lexi PUMA continues to optimize The FIFA World Cup™ in PUMA becomes the official kit PUMA’s global ”Forever With the finalization of the PUMA reissues the Becker Lewis Hamilton of PUMA PUMA and Rihanna powerful football boot USA, PUMA starts rolling national kits for its eight Thompson becomes the its organizational setup Brazil proves to be a great partner of top English Premier Faster” campaign, relocation of its Global and OG, the classic mid-top partnered MERCEDES AMG announce a new multi- to date, the evoPOWER. out its “PUMA Lab” retail national football teams second-youngest major – with the closure of the stage for PUMA’s innovative League club Arsenal FC. The the biggest marketing European Retail Organiza- shoe that 17-year-old PETRONAS F1 team wins year partnership, starting Inspired by barefoot concept in over 125 doors heading to the World Cup winner in LPGA Tour PUMA Village Development kits and eye-catching partnership kicks off with the campaign in the company’s tion from Oensingen, Swit- Boris Becker wore during his second drivers’ World January 2015.