Creative Flash Photography by John Schutt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Camera Collection & More

09/29/21 01:30:33 Camera Collection & More Auction Opens: Tue, Feb 7 7:00am PT Auction Closes: Thu, Feb 9 10:00am PT Lot Title Lot Title 500 Semi Centennial #1 Camera w/Tripod 532 Lot of 6 Camera's 501 Large Camera w/Tripod 533 Kodak 3A Autographic Folding Pocket Camera 502 3 Photo's of Mt. St. Helen's Erupting 534 2 - Polaroid Automatic 210 Camera's 503 Wanted Poster 535 1903 Wanted Postcard 504 2 Reproduction Photo's of Paradise 536 Lot of 9 Camera's 505 Photo Reproduction of SF Train, Wagon Train 537 Alpex Deluxe Flashgun w/Box & Bear River Bridge 538 Kodak Signet 35mm Camera w/Case 506 Lot of Old Photo's in Jackets 539 Spartus Camera 507 Mixed Lot of Photo's 540 Kodak Equipment 508 Wizard of Oz Photo 541 Kodak Brownie Hawkeye w/Flash 509 Lot of Old Photo's 542 Wanted for Burglary Postcard 510 Agfa Ansco Corp Box Camera 543 Exposure Meter in Box 511 Polaroid Highlander Model 80B w/case 544 Kalimar Tripod 512 Super 8 Movie Camera by Emdeko 545 Bell & Howell Movie Camera, Lights, Projector 513 1898 No.3 Brownie Box Camera & More 514 Cine16 Kodak Movie Camera w/case 546 Kodak Camera's & More 515 1916 No. 2A Brownie Model B Camera 547 Pentax Zoom 105 Super 516 35mm Pentex ME Camera 548 Brownie Reflex in Box 517 Kodak Brownie Hawkeye Flash Camera 549 Vintage Speed Graflex, Exposure Meter, Case 518 Polaroid Automatic 100 Land Camera & More 519 35mm Argus Camera with Case 550 Spiratone Vario-Dupliscope in Box 520 Optima Tripod w/Case 551 Kodak Brownie Movie 8 Camera 521 Polaroid 800 Land Camera 552 Spartus Full Vue Camera 522 Sekonic Super -

Syntax-Brillian Corporation (BRLC)

SyntaxSyntax--BrillianBrillian CorporationCorporation (BRLC)(BRLC) April 2-3, 2007 James Li, President and Chief Operating Officer Syntax-Brillian Corporation A leading manufacturer and marketer of LCD and LCoS™ HDTVs and digital entertainment products Safe-Harbor Statement Included in this material are certain predictions, estimates, and other forward-looking statements. They are subject to risks and uncertainties that could cause the actual results to differ materially. Such risks and uncertainties include customer and market concentration, increased competition, supplier difficulties, and other similar issues. These risks and uncertainties, as well as other important factors relating to our business, are described in the Company’s filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission. 2 Nasdaq BRLC Share price (52wk range): $2.02-11.70 Closed Price on March 28, 2007: $8.41 Shares outstanding*: 60.0 million Average daily trading volume: 3 million shares TTM revenues: $436 million Cash & cash equivalents: $23.2 million Total assets: $396.3 million Working capital: $61.6 million Stockholders’ equity: $130.8 million Fiscal year-end: June 30 * Shares Outstanding as of Feb 13, 2007 Other data as of Dec 31, 2006. 3 Genesis of Syntax-Brillian ► Syntax-Brillian merger completed November 30, 2005 ► Acquired Vivitar Corporation on November 21, 2006 ™ ► Strong patent portfolio in LCD and LCoS technology and imaging technology ► Products for consumer/retail and custom installation ► Broad distribution channels ► 267 employees ► NASDAQ: BRLC 4 Olevia™ -

DVR 988HD Wi-Fi Action Camera

DVR 988HD Wi-Fi Action Camera Dual Lens 360° View User Manual © 2016 Sakar International, Inc. All rights reserved. Windows and the Windows logo are registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation. All other trademarks are the property of their respective companies. CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 3 What’s Included ............................................................................................................................ 4 Parts of the Camera ..................................................................................................................... 5 Initial Setup .................................................................................................................................. 6 CHARGING THE BATTERY ............................................................................................................................................................. 6 INSTALLING THE MICRO SD MEMORY CARD ..................................................................................................................................... 7 POWERING ON – OFF / POWER SAVE............................................................................................................................................. 8 USING THE CAMERA................................................................................................................................................................... 8 -

Lens Mount and Flange Focal Distance

This is a page of data on the lens flange distance and image coverage of various stills and movie lens systems. It aims to provide information on the viability of adapting lenses from one system to another. Video/Movie format-lens coverage: [caveat: While you might suppose lenses made for a particular camera or gate/sensor size might be optimised for that system (ie so the circle of cover fits the gate, maximising the effective aperture and sharpness, and minimising light spill and lack of contrast... however it seems to be seldom the case, as lots of other factors contribute to lens design (to the point when sometimes a lens for one system is simply sold as suitable for another (eg large format lenses with M42 mounts for SLR's! and SLR lenses for half frame). Specialist lenses (most movie and specifically professional movie lenses) however do seem to adhere to good design practice, but what is optimal at any point in time has varied with film stocks and aspect ratios! ] 1932: 8mm picture area is 4.8×3.5mm (approx 4.5x3.3mm useable), aspect ratio close to 1.33 and image circle of ø5.94mm. 1965: super8 picture area is 5.79×4.01mm, aspect ratio close to 1.44 and image circle of ø7.043mm. 2011: Ultra Pan8 picture area is 10.52×3.75mm, aspect ratio 2.8 and image circle of ø11.2mm (minimum). 1923: standard 16mm picture area is 10.26×7.49mm, aspect ratio close to 1.37 and image circle of ø12.7mm. -

Vivicam X137 Digital Camera

ViviCam X137 Digital Camera User Manual © 2009-2012 Sakar International, Inc. All rights reserved. Windows and the Windows logo are registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation. All other trademarks are the property of their respective companies. Table of Contents Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................2 What’s Included ....................................................................................................................................2 Parts of the Camera ..............................................................................................................................3 Initial Camera Setup .............................................................................................................................4 Main Camera Modes .............................................................................................................................8 Camera Technical Specifications ..........................................................................................................9 Computer System Requirements ........................................................................................................10 Powering ON/OFF Your Digital camera............................................................................................... 11 Changing Camera Mode .....................................................................................................................12 -

Vivicam 7022 Digital Camera

ViviCam 7022 Digital Camera User Manual © 2010 Sakar International, Inc. All rights reserved. Windows and the Windows logo are registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation. All other trademarks are the property of their respective companies. Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 2 What‟s Included ............................................................................................................................ 2 Parts of the Camera ..................................................................................................................... 3 Initial Camera Setup ..................................................................................................................... 4 Main Camera Modes .................................................................................................................... 7 Camera Technical Specifications .................................................................................................. 8 Computer System Requirements – WINDOWS OS ..................................................................... 9 Computer System Requirements – MAC OS ............................................................................... 9 Using Your Digital Camera ......................................................................................................... 10 Changing Camera Mode ........................................................................................................... -

Vivicam XX14 Digital Camera

ViviCam XX14 Digital Camera User Manual © 2009-2016 Sakar International, Inc. All rights reserved. Windows and the Windows logo are registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation. All other trademarks are the property of their respective companies. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 2 Getting to Know Your Camera ...................................................................................................... 2 What’s Included ............................................................................................................................ 3 Parts of the Camera ..................................................................................................................... 4 Initial Camera Setup ..................................................................................................................... 5 Main Camera Modes .................................................................................................................... 9 Camera Technical Specifications ................................................................................................ 10 Computer System Requirements ................................................................................................ 11 Powering the Camera On/Off ..................................................................................................... 12 Changing Camera Mode ........................................................................................................... -

06Ba54c425e4b8570c2b686b5c

http://people.smu.edu/rmonagha/third/mfg.html Third Party Lens Manufacturers by Robert Monaghan Related Local Links: Cautionary Tale on Fitting a Tokina Lens to a Minolta Maxxum Camera (Peter Van Eyk) Samigon Lenses Related Links: About Dr. Optiks Camera Mount Adapter FAQ (interchangeable mounts) Canon Camera Museum Chinon 35mm Pages Japan Photography History Kalimar Kalimex 35mm Lenses (post-soviet Ukraine/Czech) Kalimex (Kiev) My View on Mfgers (Klaus Schroiff) Nikon Corp. History Optical Glass Manufacturers Promaster Samsung History Samyang/Phoenix Short History of Japanese Lenses Sicor Optics Sigma Lens Site [02/00] Sigma Lenses Soligor T2 Lenses (for Miranda) [11/2002] Soligor Lenses [11/2002] Spiratone History Tamron Tokina Tokina (UK) Vivitar Third Party Lens Makers U.S. Importer/Distributors Name on Lens Manufacturers (country) Acetar Ace Optical Co. Ltd. (Japan) Actinar Aetna Optix Inc. Adorama Camera Co. Adorama (numerous mfgers) Alto Yamasaki Optical Co. Ltd. (Japan) Angenieux Angenieux Corp. (French) Aragon Photo Clearing Inc. Asanuma Tokina Optical Co. Ltd. (Japan) Bausch and Lomb Inc. Baltar (numerous mfgers) Bushnell Bausch and Lomb Inc. (numerous mfgers) Cambron Cambridge Camera Exchange Inc. Cimko Cima Kogaku Corp. Ltd. (Japan) Coligon Aetna Optix Inc. Congo Yamasaki Optical Co. Ltd. (Japan) CPC Combined Products Corp. CPO Century Precision Optics (USA) Cosina Cosina Inc./Samyang Corp. (Korea) Dejur Photo International Inc. Eitar Reeves Photographic Inc. Enna Europhot Inc. Eyemik Mitake Optical Co. Ltd. (Japan) Hi-Lux Nissin Koki Co. Ltd. (Japan) Kenlock Kenlock Corp. (Japan) Kiev/USA Kiev Arsenal (Ukraine) Kalimex s.r.o. (Czech) Kilfit Heinz Kilfit Munchen Corp. (West Germany?) Kimunor Kimura Seimitsu Kogyo Co. -

Cult Classic Third Party Lenses by Robert Monaghan Angenieux (France)

http://medfmt.8k.com/third/cult.html Cult Classic Third Party Lenses by Robert Monaghan Angenieux (France) Angenieux Lenses from mid-1980s F/l f/stop 25mm 1.4 75mm 2.5 180mm 2.3 35-70 2.5 70-210 3.5 See listing for prices Angenieux is a French third party lens manufacturer that ranks with Schneider and Zeiss as one of the world's top lens makers. Angenieux lenses are unfamiliar to most 35mm SLR users because they are very expensive and come in only a few mounts, chiefly Leica. To a Leica user, a top quality Angenieux 70-210mm f/3.5 zoom for only $1,845 in 1983 is a bargain ;-) (that's $3,000+ in today's 1998 dollarettes). Some of their earlier preset lenses were much less expensive, but still multiples of the cost of similar speed and focal length lenses. Still, the name is generally associated with top optical quality, despite Angenieux's status as a third party lens maker from a country (France) not generally associated with manufacturing 35mm SLR optics. Angenieux 90mm f/1.8 Angenieux's cult status started early. One example was their development of a super-fast but remarkably high quality 90mm f/1.8 optic sold in the 1950s and 1960s. This Angenieux 90mm f/1.8 is an example of a surprisingly fast lens that was originally available for the M42 Universal thread mount popularized by Pentax and others. These lenses had manual diaphragms for use with these older stopped-down manual cameras. The lens is heavy for a short telephoto at over 18 ounces, but it can close-focus to under 3 feet. -

TECHNOLOGY TOOLS of the TRAD E

TECHNOLOGY TOOLS of the TRAD E and white—and has a plastic an ID and password each time. sage and gives you the choice case with the back and sides A number of other improve - to view or ignore it. Or you can milled from a single piece of ments include a five-element, immediately switch to the spe - polycarbonate. Apple has also eight-megapixel f/2.2 photo cific Galaxy device you received made covers of soft-feel silicon lens, two flashes for color cor - the message on by using the to coordinate with the 5c colors. rection, automatic image stabi - Smart Relay feature. An internal steel frame adds lization, face detection and geo - A built-in speaker lets you strength to the body. tagging, panorama and burst make hands-free calls, and S The iPhone 5s is available in mode for best picture choice, Voice enables you to draft mes - Apple iPhones slate, silver, and gold models. It 1,080-pixel HD video, and 120 sages, create new calendar en - As promised, Apple released also has a new basic chip, the frames-per-second slow motion. tries, set alarms, and check the two new iPhones in September, A7 with an M7 motion co - The four-inch retina display has replacing the iPhone 5 with two processor. Both phones are on a resolution of 1,136 640. new versions: the iPhone 5s and iOS 7, which was rolled out two An improved Siri system has the 5c. weeks after the announcement, Wikipedia inline Web and photo Designed to capture the and the new operating system searches. -

DVR 985HD Digital Video Camera

DVR 985HD Digital Video Camera User Manual © 2009-2012 Sakar International, Inc. All rights reserved. Windows and the Windows logo are registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation. All other trademarks are the property of their respective companies. Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 2 What‟s Included ............................................................................................................................ 2 Parts of the Camera ..................................................................................................................... 3 Initial Camera Setup ..................................................................................................................... 4 Main Camera Modes .................................................................................................................... 9 Camera Technical Specifications ................................................................................................ 10 Computer System Requirements ................................................................................................ 11 Charging the Lithium Battery ...................................................................................................... 12 Using Your DVR ......................................................................................................................... 13 Changing Camera Mode ........................................................................................................... -

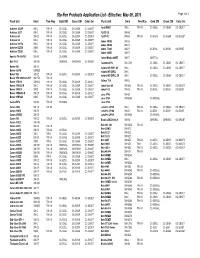

Sto-Fen Products Application List 0.1 MB

Sto-Fen Products Application List - Effective: May 05, 2019 Page 1 of 3 Flash Unit Omni Two-WayGold OM Green OM Color Set Flash Unit Omni Two-WayGold OM Green OM Color Set Achiever 260AF OM-C TW-UNI OC-CBGL OC-CBGR OC-CBSET Focal M500T OM-C TW-UNI OC-CBGL OC-CBGR OC-CBSET Achiever 260T OM-C TW-UNI OC-CBGL OC-CBGR OC-CBSET Fuji EF-20 OM-RQ Achiever 630 OM-EZ TW-UNI OC-EZGL OC-EZGR OC-EZSET Fuji EF-42 OM-600 TW-UNI OC-600GL OC-600GR OC-600SET Achiever 828 OM-C TW-UNI OC-CBGL OC-CBGR OC-CBSET Godox AD200 OM-ES Achiever 828TW OM-C TW-UNI OC-CBGL OC-CBGR OC-CBSET Godox AD200 OM-ES Achiever DZ260 OM-B TW-UNI OC-CBGL OC-CBGR OC-CBSET Godox TT685 OM-EY OC-EYGL OC-EYGR OC-EYSET Achiever TZ250 OM-C TW-UNI OC-CBGL OC-CBGR OC-CBSET Godox V860II OM-EY Aperlite YH-500-N/C OM-900 OC-900GL Hahnel Modus 600RT OM-ET OM-ETGL Bolt V-510 OM-EW OM-EWGL OM-EWGR OC-EWSET Hasselblad Pro OM-CT45 OC-CBGL OC-CBGR OC-CBSET Bower 680 OM-300 Insignia NS-DXFL CN OM-C OC-CBGL OC-CBGR OC-CBSET Bower 829TW OM-MZ2 Insignia NS-DXFL2 OM-C Bower 958 OM-EZ TW-UNI OC-EZGL OC-EZGR OC-EZSET Insignia NS-DXFL2 CN OM-C OC-CBGL OC-CBGR OC-CBSET Bower SFD 926N/O/C/S/P OM-PZ8 TW-UNI Bower SFD328 OM-MZ3 TW-UNI OC-MZGL OC-MZGR OC-MZSET Kalimar T-36 OM-ES Bower SFD35C/N OM-C TW-UNI OC-CBGL OC-CBGR OC-CBSET Kodak Gear AF OM-MZ3 TW-UNI OC-MZGL OC-MZGR OC-MZSET Bower SFD52N OM-B TW-UNI OC-CBGL OC-CBGR OC-CBSET Kodak P-20 OM-EX TW-UNI OC-EXGL OC-EXGR OC-EXSET Bower SFD680C/N OM-EY TW-UNI OC-EYGL OC-EYGR OC-EYSET Leica SF40 OM-400 Bower SFD728N OM-B TW-UNI OC-CBGL OC-CBGR OC-CBSET Leica SF58