The Sue Exhibition Educators' Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3H?;Lnbcha Nb? 1?=L?Nm I@

3H?;LNBCHANB?1?=L?NMI@ #>O=;NIL%OC>? 1?=IH>#>CNCIH @C?F>GOM?OGILA13# 'HMC>? ;=EALIOH>'H@ILG;NCIH *?MMIHM@IL%L;>?M] >>CNCIH;F0?MIOL=?M 'HNLI>O=NCIH Unearthing the Secrets of SUE No dinosaur in the world compares to SUE—the largest, most complete, and best preserved Tyrannosaurus rex ever discovered. In May 2000, the unveiling of her 67-million-year-old skeleton at The Field Museum made global headlines. Since then, more than 16 million visitors have marveled over Chicago’s prehistoric giant. Using the story of SUE to captivate students’ imagination, the Unearthing the Secrets of SUE Educator Guide takes pre-k through eighth-grade students on an interactive exploration of SUE at The Field Museum and the scientific insights she’s providing about the world in which she lived. The lessons in this guide will engage students in the science of SUE by: • providing students unique access to SUE, the largest, most complete, and best preserved TYRANNOSAURUS REX ever discovered; • providing students with hands-on activities that enable them to investigate by making observations, developing hypotheses, questioning assumptions, testing ideas, and coming to conclusions; • introducing students to careers in science by highlighting the wide professional expertise involved in the SUE project; and • introducing students to the countless resources available to them through The Field Museum including field trips, and online research and interactive learning opportunities. How to Use this Guide • Detailed Background Information is provided to support educators in sharing the story of SUE with students. Use this information to prepare yourself and your students for learning about SUE. -

Flesh: the Dino Files PDF Book

FLESH: THE DINO FILES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Pat Mills,Geofrey Miller,Kevin O'Neill,Ramon Sola,Jamie McKay | 272 pages | 15 Sep 2011 | Rebellion | 9781907992261 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom Flesh: The Dino Files PDF Book Collected editions. Mayhem ensues. His comics are notable for their violence and anti-authoritarianism. New Account or Log In. This arc remained unfinished and was followed by the sequel "Midnight Cowboys" in Recent History. For printed books, we have performed high- resolution scans of an original hardcopy of the book. Dec 10, Matthew Candelaria rated it really liked it. These products were created by scanning an original printed edition. He is best known for creating AD and playing a major part in the development of Judge Pat Mills, born in and nicknamed 'the godfather of British comics', is a comics writer and editor who, along with John Wagner, revitalised British boys comics in the s, and has remained a leading light in British comics ever since. These PDF files are digitally watermarked to signify that you are the owner. In the series, cowboys from the future travel to the prehistoric past to harvest dinosaurs for their meat. Trivia Old One Eye, the anti-hero of the first arc, is the mother of the Judge Dredd villain Satanus , a Tyrannosaurus rex that rules a park populated with cloned dinosaurs. The first story starts with the life of cowboys herding dinosaurs. It's very clear from early on that the writers are just itching to get to the scenes of the capitalist exploiters of the downtrodden dinos getting their gory just deserts. -

Ancient Ship Discovered!

Informational Text by Susan Evento PAIRED READ Ancient Ship Discovered! FC_BC_CR14_LR_G2_U6W3_L20_ELL_118960.indd 2 3/12/12 5:53 PM Program: CR14 Component: LR PDF Vendor: SRM Grade: 2 STRATEGIES & SKILLS Comprehension Vocabulary Strategy: Summarize exploration, important, Skill: Main Idea and machines, prepare, Key Details repair, result, scientific, teamwork Phonics Consonant + le (el, al) ELL Vocabulary syllables discovery, research Vocabulary Strategy Content Standards Greek and Latin Roots Science Science as Inquiry Word count: 725** Photography Credit: Cover Image Sources/(bkgd) Datacraft Co Ltd/imagenavi/Getty Images, (inset) Sue Ogrocki/Reuters/CORBIS **The total word count is based on words in the running text and headings only. Numerals and words in captions, labels, diagrams, charts, and sidebars are not included. Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written consent of The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., including, but not limited to, network storage or transmission, or broadcast for distance learning. Send all inquiries to: McGraw-Hill Education Two Penn Plaza New York, New York 10121 ISBN: 978-0-02-118960-1 MHID: 0-02-118960-9 Printed in the United States. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 DOC 17 16 15 14 13 12 A IFBC_CR14_LR_G2_U6W3_L20_ELL_118960.indd 2 2/14/12 3:18 PM Program: CR14 Component: LR PDF Vendor: SRM Grade: 2 Genre Informational Text Essential Question Why is teamwork important? by Susan Evento Chapter 1 The Mighty T. Rex. -

Searchable PDF (No Class Notes) (9.906Mb)

The paper used in this publication is manufactured from 100%-recycled fiber of which 50% is recovered from Post Consumer sources. This product is made exclusively for New Leaf Paper in San Francisco, California by Plainwell Paper Company and was offered to Kalamazoo College with their permis Jllege learning experience takes this young member of sion. New Leaf Paper is nationally known for their active role in the design and marketing of paper products that II which people and communities the power of that are entirely recycled and recyclable. Two members of the Kalamazoo College Jirectly, as she uses it to build her future. Class of 1963 had active roles in the manufacture of these items. rndations that support Kalamazoo College. The others 1e. All are vital. Your Annual Fund gift makes the ~e possible for young people like her. Most annual fund gifts are applied to student scholarships and program or facility improvements. Annual fund gifts are unrestricted, which confers upon the College the opportunity to use them in ways to best support the K-Plan. And the degree of Annual Fund participation unlocks additional gifts from corporations and foundations. Alumni participation is one of the first facts requested by grant officers when they consider major funding proposals from the College. So thank you again, alumni and friends. For the second consecutive year the Annual Fund reached and exceeded its goal. It will help enlighten futures. KALAMAZOO COLLEGE A~fiutd 1 9 9 8 - 1 9 9 9 Time will tell where her Kalamazoo College learning experience takes this young member of the Class of 1999; and time will tell which people and communities the power of that experience will touch, directly and indirectly, as she uses it to build her future. -

Theropod Teeth from the Upper Maastrichtian Hell Creek Formation “Sue” Quarry: New Morphotypes and Faunal Comparisons

Theropod teeth from the upper Maastrichtian Hell Creek Formation “Sue” Quarry: New morphotypes and faunal comparisons TERRY A. GATES, LINDSAY E. ZANNO, and PETER J. MAKOVICKY Gates, T.A., Zanno, L.E., and Makovicky, P.J. 2015. Theropod teeth from the upper Maastrichtian Hell Creek Formation “Sue” Quarry: New morphotypes and faunal comparisons. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 60 (1): 131–139. Isolated teeth from vertebrate microfossil localities often provide unique information on the biodiversity of ancient ecosystems that might otherwise remain unrecognized. Microfossil sampling is a particularly valuable tool for doc- umenting taxa that are poorly represented in macrofossil surveys due to small body size, fragile skeletal structure, or relatively low ecosystem abundance. Because biodiversity patterns in the late Maastrichtian of North American are the primary data for a broad array of studies regarding non-avian dinosaur extinction in the terminal Cretaceous, intensive sampling on multiple scales is critical to understanding the nature of this event. We address theropod biodiversity in the Maastrichtian by examining teeth collected from the Hell Creek Formation locality that yielded FMNH PR 2081 (the Tyrannosaurus rex specimen “Sue”). Eight morphotypes (three previously undocumented) are identified in the sample, representing Tyrannosauridae, Dromaeosauridae, Troodontidae, and Avialae. Noticeably absent are teeth attributed to the morphotypes Richardoestesia and Paronychodon. Morphometric comparison to dromaeosaurid teeth from multiple Hell Creek and Lance formations microsites reveals two unique dromaeosaurid morphotypes bearing finer distal denticles than present on teeth of similar size, and also differences in crown shape in at least one of these. These findings suggest more dromaeosaurid taxa, and a higher Maastrichtian biodiversity, than previously appreciated. -

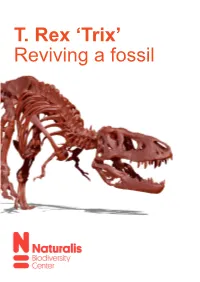

T. Rex 'Trix' Reviving a Fossil

T. Rex ‘Trix’ Reviving a fossil Teacher’s guide Dear teacher, Here’s the educator’s guide for the 3D printing activity “Print your own T.rex”. This document contains information about: - The structure of the activity - The prints - Background information on T. rex Trix of Naturalis - Assembly Instructions - References to necessary resources and helpful tips Plan your lesson according to your own best judgment. Work on another activity, while the 3D printer is running. In total, the students will be working on this lesson effectively for about a day part. For questions about printing, please contact your local technical support team via this link: https://ultimaker.com/contact Have fun printing and investigating! Kind regards, Matthijs Graner [email protected] Educational developer Naturalis 1 Lesson plan Short description of the activity During the activity, you will print different bones of Trix - one at a time. Students will wonder about what will come out of the printer. They will think about what it is, where it came from and where it belongs. They will think about the form and function and will be able to do calculations on steps and scale. Eventually, your students will put together Trix into a model (scale 1:15) for the classroom. Target audience Upper primary education (grade 4-7). Objectives - Students learn about the form and function of dinosaur bones. - Students make connections between the bones of contemporary animals and their own skeletons. - Students are able to describe broadly how T. rex lived. - Students learn how scientists research dinosaur fossils. - Students learn about the possibilities of 3D printing. -

D Inosaur Paleobiology

Topics in Paleobiology The study of dinosaurs has been experiencing a remarkable renaissance over the past few decades. Scientifi c understanding of dinosaur anatomy, biology, and evolution has advanced to such a degree that paleontologists often know more about 100-million-year-old dinosaurs than many species of living organisms. This book provides a contemporary review of dinosaur science intended for students, researchers, and dinosaur enthusiasts. It reviews the latest knowledge on dinosaur anatomy and phylogeny, Brusatte how dinosaurs functioned as living animals, and the grand narrative of dinosaur evolution across the Mesozoic. A particular focus is on the fossil evidence and explicit methods that allow paleontologists to study dinosaurs in rigorous detail. Scientifi c knowledge of dinosaur biology and evolution is shifting fast, Dinosaur and this book aims to summarize current understanding of dinosaur science in a technical, but accessible, style, supplemented with vivid photographs and illustrations. Paleobiology Dinosaur The Topics in Paleobiology Series is published in collaboration with the Palaeontological Association, Paleobiology and is edited by Professor Mike Benton, University of Bristol. Stephen Brusatte is a vertebrate paleontologist and PhD student at Columbia University and the American Museum of Natural History. His research focuses on the anatomy, systematics, and evolution of fossil vertebrates, especially theropod dinosaurs. He is particularly interested in the origin of major groups such Stephen L. Brusatte as dinosaurs, birds, and mammals. Steve is the author of over 40 research papers and three books, and his work has been profi led in The New York Times, on BBC Television and NPR, and in many other press outlets. -

A Huge Predatory Dinosaur, Built to Swim

Science Now Discoveries from the world of science and medicine Spinosaurus: A huge predatory dinosaur, built to swim A digital skeletal reconstruction and transparent flesh outline of Spinosaurus aegyptiacus. The bones suggest this dinosaur was built to swim. Color codes show the origin of different parts of the digital skeletal model. (Model by Tyler Keillor, Lauren Conroy and Erin Fitzgerald, Ibrahim et al., Science/AAAS) By AMINA KHAN SEPTEMBER 11, 2014, 9:45 PM inosaurs ruled the land for millions of years. Now scientists have discovered a fearsome D species that could have wreaked havoc in its prehistoric waters. An unusual fossil whose parts were flung across two continents appears to be the first known semi-aquatic dinosaur, according to a report published Thursday by the journal Science. Measuring 9 feet longer than a Tyrannosaurus rex, the 95-million-year-old Spinosaurus aegyptiacus would have been the largest predatory dinosaur to walk the Earth. But it had several features that strongly suggest a life spent largely submerged in the water, including nostrils pushed toward the top of its skull and diagonally jutted teeth ideal for snapping up fish. “It was not a balancing, two-legged animal on land,” said study coauthor Paul Sereno, a paleontologist at the University of Chicago. “It would have been something very peculiar.” The differences between this Spinosaurus and other theropods are apparent from head to toe. Most theropods, like T. rex, ran on two powerful legs and had small, spindly arms. By contrast, the 50-foot-long Spinosaurus had muscular arms with blade-like claws that could have nabbed slippery prey, and shorter legs that were ill-equipped to walk on land. -

Late Pleistocene Birds from Kingston Saltpeter Cave, Southern Appalachian Mountains, Georgia

Bull. Fla. Mus. Nat. Hist. (2005) 45(4):231-248 231 LATE PLEISTOCENE BIRDS FROM KINGSTON SALTPETER CAVE, SOUTHERN APPALACHIAN MOUNTAINS, GEORGIA David W. Steadman1 Kingston Saltpeter Cave, Bartow County, Georgia, has produced late Quaternary fossils of 38 taxa of birds. The presence of extinct species of mammals, and three radiocarbon dates on mammalian bone collagen ranging from approximately 15,000 to 12,000 Cal B.P., indicate a late Pleistocene age for this fauna, although a small portion of the fossils may be Holocene in age. The birds are dominated by forest or woodland species, especially the Ruffed Grouse (Bonasa umbellus) and Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius). Species indicative of brushy or edge habitats, wetlands, and grasslands also are present. They include the Greater Prairie Chicken (Tympanuchus cupido, a grassland indicator) and Black-billed Magpie (Pica pica, characteristic of woody edges bordering grasslands). Both of these species reside today no closer than 1000+ km to the west (mainly northwest) of Georgia. An enigmatic owl, perhaps extinct and undescribed, is represented by two juvenile tarsometatarsi. The avifauna of Kingston Saltpeter Cave suggests that deciduous or mixed deciduous/coniferous forests and woodlands were the dominant habitats in the late Pleistocene of southernmost Appalachia, with wetlands and grasslands present as well. Key Words: Georgia; late Pleistocene; southern Appalachians; Aves; extralocal species; faunal change INTRODUCTION dates have been determined from mammal bones at Numerous late Pleistocene vertebrate faunas have been KSC. The first (10,300 ± 130 yr B.P.; Beta-12771, un- recovered from caves and other karst features of the corrected for 13C/12C; = 12,850 – 11,350 Cal B.P.) is Appalachian region (listed in Lundelius et al. -

A Census of Dinosaur Fossils Recovered from the Hell Creek and Lance Formations (Maastrichtian)

The Journal of Paleontological Sciences: JPS.C.2019.01 1 TAKING COUNT: A Census of Dinosaur Fossils Recovered From the Hell Creek and Lance Formations (Maastrichtian). ______________________________________________________________________________________ Walter W. Stein- President, PaleoAdventures 1432 Mill St.. Belle Fourche, SD 57717. [email protected] 605-210-1275 ABSTRACT: A census of Hell Creek and Lance Formation dinosaur remains was conducted from April, 2017 through February of 2018. Online databases were reviewed and curators and collections managers interviewed in an effort to determine how much material had been collected over the past 130+ years of exploration. The results of this new census has led to numerous observations regarding the quantity, quality, and locations of the total collection, as well as ancillary data on the faunal diversity and density of Late Cretaceous dinosaur populations. By reviewing the available data, it was also possible to make general observations regarding the current state of certain exploration programs, the nature of collection bias present in those collections and the availability of today's online databases. A total of 653 distinct, associated and/or articulated remains (skulls and partial skeletons) were located. Ceratopsid skulls and partial skeletons (mostly identified as Triceratops) were the most numerous, tallying over 335+ specimens. Hadrosaurids (Edmontosaurus) were second with at least 149 associated and/or articulated remains. Tyrannosaurids (Tyrannosaurus and Nanotyrannus) were third with a total of 71 associated and/or articulated specimens currently known to exist. Basal ornithopods (Thescelosaurus) were also well represented by at least 42 known associated and/or articulated remains. The remaining associated and/or articulated specimens, included pachycephalosaurids (18), ankylosaurids (6) nodosaurids (6), ornithomimids (13), oviraptorosaurids (9), dromaeosaurids (1) and troodontids (1). -

40Th Anniversary Primer

200040TH ANNIVERSARY AD PRIMER 40TH INSERT.indd 1 07/02/2017 15:28 JUDGE DREDD FACT-FILE First appearance: 2000 AD Prog 2 (1977) Created by: John Wagner and Carlos Ezquerra ////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// Judge Dredd is a totalitarian cop in Mega- Blue in a sprawling ensemble-led police an awful lot of blood in his time. City One, the vast, crime-ridden American procedural about Dredd cleaning up crime East Coast megalopolis of over 72 million and corruption in the deadly Sector 301. With stories such as A History of Violence people set 122 years in the future. Judges and Button Man, plus your hard-boiled possess draconian powers that make them Mega-City Undercover Vols. 1-3 action heroes like Dredd and One-Eyed judge, jury, and executioner – allowing them Get to know the dark underbelly of policing Jack, your love of crime fiction is obvious. to summarily execute criminals or arrest Mega-City One with Justice Department’s Has this grown over the years? What citizens for the smallest of crimes. undercover division. Includes Andy Diggle writers have influenced you? and Jock’s smooth operator Lenny Zero, and Created by John Wagner and Carlos Ezquerra Rob Williams, Henry Flint, Rufus Dayglo and JW: I go through phases. Over the past few in 1977, Dredd is 2000 AD’s longest- D’Israeli’s gritty Low Life. years I have read a lot of crime fiction, running character. Part dystopian science enjoyed some, disliked much. I wouldn’t like fiction, part satirical black comedy, part DREDD: Urban Warfare to pick any prose writer out as an influence. -

Cranial Anatomy of Allosaurus Jimmadseni, a New Species from the Lower Part of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic) of Western North America

Cranial anatomy of Allosaurus jimmadseni, a new species from the lower part of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic) of Western North America Daniel J. Chure1,2,* and Mark A. Loewen3,4,* 1 Dinosaur National Monument (retired), Jensen, UT, USA 2 Independent Researcher, Jensen, UT, USA 3 Natural History Museum of Utah, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA 4 Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA * These authors contributed equally to this work. ABSTRACT Allosaurus is one of the best known theropod dinosaurs from the Jurassic and a crucial taxon in phylogenetic analyses. On the basis of an in-depth, firsthand study of the bulk of Allosaurus specimens housed in North American institutions, we describe here a new theropod dinosaur from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of Western North America, Allosaurus jimmadseni sp. nov., based upon a remarkably complete articulated skeleton and skull and a second specimen with an articulated skull and associated skeleton. The present study also assigns several other specimens to this new species, Allosaurus jimmadseni, which is characterized by a number of autapomorphies present on the dermal skull roof and additional characters present in the postcrania. In particular, whereas the ventral margin of the jugal of Allosaurus fragilis has pronounced sigmoidal convexity, the ventral margin is virtually straight in Allosaurus jimmadseni. The paired nasals of Allosaurus jimmadseni possess bilateral, blade-like crests along the lateral margin, forming a pronounced nasolacrimal crest that is absent in Allosaurus fragilis. Submitted 20 July 2018 Accepted 31 August 2019 Subjects Paleontology, Taxonomy Published 24 January 2020 Keywords Allosaurus, Allosaurus jimmadseni, Dinosaur, Theropod, Morrison Formation, Jurassic, Corresponding author Cranial anatomy Mark A.