D.3.5: Final Analysis Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Current Affairs Questions and Answers for February 2010: 1. Which Bollywood Film Is Set to Become the First Indian Film to Hit T

ho”. With this latest honour the Mozart of Madras joins Current Affairs Questions and Answers for other Indian music greats like Pandit Ravi Shankar, February 2010: Zakir Hussain, Vikku Vinayak and Vishwa Mohan Bhatt who have won a Grammy in the past. 1. Which bollywood film is set to become the first A. R. Rahman also won Two Academy Awards, four Indian film to hit the Egyptian theaters after a gap of National Film Awards, thirteen Filmfare Awards, a 15 years? BAFTA Award, and Golden Globe. Answer: “My Name is Khan”. 9. Which bank became the first Indian bank to break 2. Who becomes the 3rd South African after Andrew into the world’s Top 50 list, according to the Brand Hudson and Jacques Rudoph to score a century on Finance Global Banking 500, an annual international Test debut? ranking by UK-based Brand Finance Plc, this year? Answer: Alviro Petersen Answer: The State Bank of India (SBI). 3. Which Northeastern state of India now has four HSBC retain its top slot for the third year and there are ‘Chief Ministers’, apparently to douse a simmering 20 Indian banks in the Brand Finance® Global Banking discontent within the main party in the coalition? 500. Answer: Meghalaya 10. Which country won the African Cup of Nations Veteran Congress leader D D Lapang had assumed soccer tournament for the third consecutive time office as chief minister on May 13, 2009. He is the chief with a 1-0 victory over Ghana in the final in Luanda, minister with statutory authority vested in him. -

Achilles and the Caucasus

1 Achilles and the Caucasus Kevin Tuite1 Université de Montréal Achilles, the hero of the Iliad, is based on a mythical personnage of pre-Homeric antiquity. The details of his “biography” can be reconstructed from other sources, most notably the Library of Apollodorus. In this article features relating to the parentage, birth, childhood and career of Achilles are compared to those of legendary figures from the Caucasus region, in particular the Svan (Kartvelian) Amiran, the Ossetic Batradz and the Abkhazian Tswitsw. I argue that the striking correspondances between Achilles and his distant cousins from beyond the Black Sea derive from a mythic framework in which were represented the oppositions between domesticated and savage space, and between settled life, with its alliances and obligations, and a sort of male- fantasy life of exploitation and unconstraint. The core elements of the figure I term “Proto-Achilles” appear to be quite ancient, and can be added to the growing body of evidence relating to ancient contacts between early Indo-European-speaking populations and the Caucasus. 0. INTRODUCTION. It appears more and more probable that the Proto-Indo-European speech community — or a sizeable component of it, in any event — was in the vicinity of the Caucasus as early as the 4th millenium BCE. According to the most widely-accepted hypothesis and its variants, Proto- Indo-European speakers are to be localized somewhere in the vast lowland region north of the Black and Caspian Seas (Gimbutas 1985, Mallory 1989, Anthony 1991). The competing reconstruction of early Indo-European [IE] migrations proposed by Gamkrelidze and Ivanov (1984) situates the Urheimat to the south of the Caucasus, in eastern Anatolia (see 1A shorter version of this paper was read at the McGill University Black Sea Conference on 25 January 1996, at the invitation of Dr. -

A Study on the Genus Chrysolina MOTSCHULSKY, 1860, with A

Genus Vol. 12 (2): 105-235 Wroc³aw, 30 VI 2001 A study on the genus Chrysolina MOTSCHULSKY, 1860, with a checklist of all the described subgenera, species, subspecies, and synonyms (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae: Chrysomelinae) ANDRZEJ O. BIEÑKOWSKI Zelenograd, 1121-107, Moscow, K-460, 103460, Russia e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT. A checklist of all known Chrysolina species is presented. Sixty five valid subgenera, 447 valid species and 251 valid subspecies are recognized. The following new synonymy is established: Chrysolina (Apterosoma MOTSCHULSKY) (=Caudatochrysa BECHYNÉ), Ch. (Synerga WEISE) (=Chrysonotum J. SAHLBERG), Ch. (Sulcicollis J. SAHLBERG) (=Minckia STRAND), Ch. (Bittotaenia MOTSCHULSKY) (=Gemellata J. SAHLBERG, partim), Ch. (Hypericia BEDEL) (=Gemellata J. SAHLBERG, partim), Ch. (Ovosoma MOTSCHULSKY) (=Gemellata J. SAHLBERG, partim, =Byrrhiformis J. SAHLBERG, partim), Ch. (Colaphoptera MOTSCHULSKY) (=Byrrhiformis J. SAHLBERG, partim), Ch. aeruginosa poricollis MOTSCHULSKY (=lobicollis FAIRMAIRE), Ch. apsilaena DACCORDI (=rosti kubanensis L.MEDVEDEV et OKHRIMENKO), Ch. fastuosa biroi CSIKI (=fastuosa jodasi BECHYNÉ, 1954), Ch. differens FRANZ (=trapezicollis BECHYNÉ), Ch. difficilis ussuriensis JACOBSON (=pubitarsis BECHYNÉ), Ch. difficilis yezoensis MATSUMURA (=exgeminata BECHYNÉ, =nikinoja BECHYNÉ), Ch. marginata marginata LINNAEUS (=finitima BROWN), Ch. pedestris GEBLER (=pterosticha FISCHER DE WALDHEIM), Ch. reitteri saxonica DACCORDI (=diluta KRYNICKI). Ch. elbursica LOPATIN is treated as a subspecies of Ch. tesari ROUBAL, Ch. unicolor alaiensis LOPATIN - as Ch. dieckmanni alaiensis, and Ch. poretzkyi JACOBSON as a subspecies of Ch. subcostata GEBLER. Ch. peninsularis BECHYNÉ is a distinct species, but a subspecies of Ch. aeruginosa, Ch. brahma TAKIZAWA is a good species, not a synonym of Ch. lia JACOBSON (= freyi BECHYNÉ), and Ch. dzhungarica JACOBSON is a good species, not a synonym of Ch. -

American Community Survey and Puerto Rico Community Survey

American Community Survey and Puerto Rico Community Survey 2016 Code List 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ANCESTRY CODE LIST 3 FIELD OF DEGREE CODE LIST 25 GROUP QUARTERS CODE LIST 31 HISPANIC ORIGIN CODE LIST 32 INDUSTRY CODE LIST 35 LANGUAGE CODE LIST 44 OCCUPATION CODE LIST 80 PLACE OF BIRTH, MIGRATION, & PLACE OF WORK CODE LIST 95 RACE CODE LIST 105 2 Ancestry Code List ANCESTRY CODE WESTERN EUROPE (EXCEPT SPAIN) 001-099 . ALSATIAN 001 . ANDORRAN 002 . AUSTRIAN 003 . TIROL 004 . BASQUE 005 . FRENCH BASQUE 006 . SPANISH BASQUE 007 . BELGIAN 008 . FLEMISH 009 . WALLOON 010 . BRITISH 011 . BRITISH ISLES 012 . CHANNEL ISLANDER 013 . GIBRALTARIAN 014 . CORNISH 015 . CORSICAN 016 . CYPRIOT 017 . GREEK CYPRIOTE 018 . TURKISH CYPRIOTE 019 . DANISH 020 . DUTCH 021 . ENGLISH 022 . FAROE ISLANDER 023 . FINNISH 024 . KARELIAN 025 . FRENCH 026 . LORRAINIAN 027 . BRETON 028 . FRISIAN 029 . FRIULIAN 030 . LADIN 031 . GERMAN 032 . BAVARIAN 033 . BERLINER 034 3 ANCESTRY CODE WESTERN EUROPE (EXCEPT SPAIN) (continued) . HAMBURGER 035 . HANNOVER 036 . HESSIAN 037 . LUBECKER 038 . POMERANIAN 039 . PRUSSIAN 040 . SAXON 041 . SUDETENLANDER 042 . WESTPHALIAN 043 . EAST GERMAN 044 . WEST GERMAN 045 . GREEK 046 . CRETAN 047 . CYCLADIC ISLANDER 048 . ICELANDER 049 . IRISH 050 . ITALIAN 051 . TRIESTE 052 . ABRUZZI 053 . APULIAN 054 . BASILICATA 055 . CALABRIAN 056 . AMALFIAN 057 . EMILIA ROMAGNA 058 . ROMAN 059 . LIGURIAN 060 . LOMBARDIAN 061 . MARCHE 062 . MOLISE 063 . NEAPOLITAN 064 . PIEDMONTESE 065 . PUGLIA 066 . SARDINIAN 067 . SICILIAN 068 . TUSCAN 069 4 ANCESTRY CODE WESTERN EUROPE (EXCEPT SPAIN) (continued) . TRENTINO 070 . UMBRIAN 071 . VALLE DAOSTA 072 . VENETIAN 073 . SAN MARINO 074 . LAPP 075 . LIECHTENSTEINER 076 . LUXEMBURGER 077 . MALTESE 078 . MANX 079 . -

Geo-Data: the World Geographical Encyclopedia

Geodata.book Page iv Tuesday, October 15, 2002 8:25 AM GEO-DATA: THE WORLD GEOGRAPHICAL ENCYCLOPEDIA Project Editor Imaging and Multimedia Manufacturing John F. McCoy Randy Bassett, Christine O'Bryan, Barbara J. Nekita McKee Yarrow Editorial Mary Rose Bonk, Pamela A. Dear, Rachel J. Project Design Kain, Lynn U. Koch, Michael D. Lesniak, Nancy Cindy Baldwin, Tracey Rowens Matuszak, Michael T. Reade © 2002 by Gale. Gale is an imprint of The Gale For permission to use material from this prod- Since this page cannot legibly accommodate Group, Inc., a division of Thomson Learning, uct, submit your request via Web at http:// all copyright notices, the acknowledgements Inc. www.gale-edit.com/permissions, or you may constitute an extension of this copyright download our Permissions Request form and notice. Gale and Design™ and Thomson Learning™ submit your request by fax or mail to: are trademarks used herein under license. While every effort has been made to ensure Permissions Department the reliability of the information presented in For more information contact The Gale Group, Inc. this publication, The Gale Group, Inc. does The Gale Group, Inc. 27500 Drake Rd. not guarantee the accuracy of the data con- 27500 Drake Rd. Farmington Hills, MI 48331–3535 tained herein. The Gale Group, Inc. accepts no Farmington Hills, MI 48331–3535 Permissions Hotline: payment for listing; and inclusion in the pub- Or you can visit our Internet site at 248–699–8006 or 800–877–4253; ext. 8006 lication of any organization, agency, institu- http://www.gale.com Fax: 248–699–8074 or 800–762–4058 tion, publication, service, or individual does not imply endorsement of the editors or pub- ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Cover photographs reproduced by permission No part of this work covered by the copyright lisher. -

Forestry & Timber News

FORESTRY & TIMBER NEWS February 2020 Issue 97 HUMAN RESOURCES FORESTRY MANAGEMENT & DIVERSIFICATION THE NEXT GENERATION OF FENCING SYSTEMS UK MANUFACTURED METAL POSTS AND FENCING ✓ , and Fencing Products ✓ Versalok® Metal Post and Clip System ✓ Hampton Box and Angle Strainer Post Systems ✓ Hampton NETTM Fixed Knot Fencing ✓ Hinge Joint Fencing ✓ PVC Coated Chain Link Fencing ✓ Galvanised Chain Link Fencing ✓ Barbed Wire ✓ Line Wires ✓ Hexagonal Wire Fencing ® Rylock Green • • Y E E A E R T G AN Te UAR ly. rm pp s and conditions a +44 (0) 1933 234070 | [email protected] | www.hamptonsteel.co.uk CONTENTS 40 | COMMUNICATING FORESTRY WIDENING THE NET TO SECURE Confor is a membership organisation OUR FUTURE WORKFORCE that promotes sustainable forestry and 42 | EDUCATION & TRAINING wood-using businesses. Confor mem- bers receive Forestry and Timber News MENTORING THE FUTURE OF for free as part of their membership. For FORESTRY more information on membership, visit VIRTUAL FIELD TRIPS TO INSPIRE www.confor.org.uk/join-us THE NEXT GENERATION OF Past issues and articles can be accessed FORESTERS online at 46 | MARKETS www.confor.org.uk/news/ftn-magazine TIMBER MARKET REPORT Non-member subscriptions: BIDDING SUBDUED AT £60 (£65 overseas). HARDWOOD AUCTION Please contact [email protected] TIMBER AUCTIONS MARKET REPORT CONFOR CONTACTS NEWS & COMMENT 53 | OBITUARY Stefanie Kaiser 55 | MACHINERY Communications and editor FTN 5 | EDITORIAL T: 0131 240 1420 CHAINSAW MILLING E: [email protected] 6 | GENERAL ELECTION ‘GET TREE PLANTING -

An Enumeration of the Crustacea Decapoda Natantia Inhabiting Subterranean Waters

/ s £ Qtaam m !957 CTttSW^ AN ENUMERATION OF THE CRUSTACEA DECAPODA NATANTIA INHABITING SUBTERRANEAN WATERS par L.-B. HOLTHUIS Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie, Leiden, Holland The present paper provides a list of the macrurous Decapod Crustacea, belonging to the supersection Natantia, that have been found in subterranean waters. The number of such species is quite small, being somewhat more than 40 in all. Of these only part are actual troglobic forms, i.e. animals that are only known from caves and have not, or only incidentally, been found in waters that are exposed to daylight. A second group is formed by species that normally live in surface waters and only occasionally are met with in subterranean habitats. No sharp line can be drawn between these two categories, the more so as at present still extremely little is known of the biology and of the ecology of most of the species. Nevertheless it was thought useful to try and make in the present paper a distinction between these two groups, of each of which a separate list is given enumerating the species in systematic order. In the first list the true troglobic forms are dealt with, the second contains those species which must be ranged under the incidental visitors of subterranean waters. Of the species placed in list I a complete synonymy is given, while also all the localities whence the species has been reported are enumerated. Furthermore remarks are made on the ecology and biology of the animals as far as these are known. In the second list only those references are cited that deal with specimens found in subterranean waters, while also some notes on the ecology of the animals and the general distribution of the species are provided. -

Icsp-Funded Projects

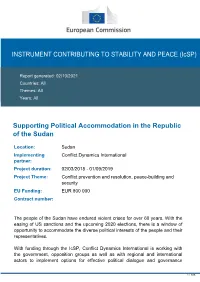

INSTRUMENT CONTRIBUTING TO STABILITY AND PEACE (IcSP) Report generated: 02/10/2021 Countries: All Themes: All Years: All Supporting Political Accommodation in the Republic of the Sudan Location: Sudan Implementing Conflict Dynamics International partner: Project duration: 02/03/2018 - 01/09/2019 Project Theme: Conflict prevention and resolution, peace-building and security EU Funding: EUR 800 000 Contract number: The people of the Sudan have endured violent crises for over 60 years. With the easing of US sanctions and the upcoming 2020 elections, there is a window of opportunity to accommodate the diverse political interests of the people and their representatives. With funding through the IcSP, Conflict Dynamics International is working with the government, opposition groups as well as with regional and international actors to implement options for effective political dialogue and governance 1 / 405 arrangements. Political representatives are given the tools to reach a sufficient degree of consensus, and encouraged to explore inclusive and coherent political processes. This is being achieved through a series of seminars and workshops (with a range of diverse stakeholders). Technical support is provided to the government as well as to main member groups within the opposition, and focus group discussions are being conducted with influential journalists and political actors at a national level. Regional and international actors are being supported in their efforts to prevent and resolve conflict through a number of initiatives. These include organising at least two coordination meetings, the provision of technical support to the African Union High-Level Implementation Panel, and consultations with groups active in the peace process. Through this support, the action is directly contributing to sustainable peace and political stability in Sudan and, indirectly, to stability and development in the Greater East African Region. -

View Article

Ecologica Montenegrina 14: 14-20 (2017) This journal is available online at: www.biotaxa.org/em Climate Changes of the Temperature of the Surface and Level of the Black Sea by the Data of Remote Sensing at the Coast of the Krasnodar Krai and the Republic of Abkhazia SERGEY A. LEBEDEV1,2, ANDREY G. KOSTIANOY4, MURAT K. BEDANOKOV3, ASIDA K. AKHSALBA5, ROZA B. BERZEGOVA3, PAVEL N. KRAVCHENKO6 1Geophysics Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Russia 2Space Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Russia 3Maykop State Technological University, Russia 4P.P.Shirshov Institute of Oceanology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Russia 5Abkhazian State University, Abkhazia 6Tver State University, Russia Received 29 August 2017 │ Accepted 1 October 2017 │ Published online 30 October 2017. Abstract Climate changes in the Black Sea basin and its water area are reflected in changes in the main parameters of the sea state: sea level and sea surface temperature (SST). To study these changes, satellite altimetry and radiometry data were used that allow analyzing the spatial-temporal variability of the interannual rate of change of these parameters over a long time interval. To study the spatial-temporal variability of the rate of SST climatic variability used remote sensing data for two intervals in 1982–2015 and 1993–2015. The results of the study showed that over the time interval 1982– 2015 that the SST near the coast of the Krasnodar Krai increase at an average rate of 0.079±0.005°C/yr, and the coast of the Republic of Abkhazia at a rate of 0.072±0.002°C/yr. -

Armed Non-State Actors and Landmines Profiles

ANALYSIS PREFACE The Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Treaty (APMBT), signed in Ottawa in 1997, intends to eliminate a whole class of conventional weapons. The fact that over 140 countries have consented to be bound by the Treaty constitutes a remarkable achievement. The progress registered with the putting the Treaty into effect is of great credit to all those involved – governments, civil society and international organizations. Nevertheless, in some of the most seriously mine-affected countries progress has been delayed or even com- promised altogether by the fact that rebel groups that use anti-personnel mines do not consider themselves bound by the commitments of the government in power. Such groups, or non-state actors (NSAs), cannot them- selves become parties to an international Treaty, even if they are willing to agree to its terms. Faced with this potential “show-stopper”, Geneva Call came forward with a revolutionary new approach to engaging NSAs in committing themselves to the substance of the APMBT. Geneva Call designed a Deed of Commitment, to be deposited with the authorities of the Republic and Canton of Geneva, which NSAs can formally adhere to. This Deed of Commitment contains the same obligations as the APMBT. It allows the lead- ers of rebel groups to assume formal obligations and to accept that their performance in implementing those obligations will be monitored by an international body. The success of this approach is illustrated by the case of Sudan. In October 2001, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A) agreed to give up their AP mines and signed the Deed of Commitment. -

2012-2013 PIMS Manual Vol 2 V1.0.1

Pennsylvania Department of Education Pennsylvania Information Management System Volume 2 USER MANUAL Ron Tomalis Secretary of Education 2012 – 2013 V 1.0.1 Pennsylvania Information Pennsylvania Management System Department of Education Table of Contents – Volume 2 – PIMS Reference Materials Appendix A – Course Codes ......................................................................................................................................3 Elementary Course Codes ......................................................................................................................................3 Departmentalized Sixth Grade Course Codes ........................................................................................................4 Dual Enrollment Course Codes ..............................................................................................................................4 Special Education Course Codes (page 1 of 3) ......................................................................................................4 ESL Course Codes (page 1 of 2) ............................................................................................................................7 Visually Impaired Course Codes (page 1 of 2) .......................................................................................................9 Hearing Impaired Course Codes (page 1 of 2) .................................................................................................... 11 Hearing Impaired Course Codes (page 2 -

Russia's Revolution

Advance Praise for Russia’S Revolution “Leon Aron is one of our very best witnesses to, and analysts of, the new Russia. His collected essays track two decades of the changes within Russia itself and in Russian and Western opinion of them. But they also present a consistent Aron voice that deserves to be heard— judicious, broad (as much at home in literature or the restaurant scene as in arms control or privatization), sanely optimistic, and invariably rendered in graceful yet unpretentious prose.” —TIMOTHY J. COLTON, professor of government and director, Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies, Harvard University “Leon Aron stands out among the West’s top Russia experts as a per- son with a 360-degree vision. He is a political scientist, sociologist, and historian, endowed with a keen understanding of the Russian economy and a passion for Russian literature and the arts. This book is a testimony to his unique breadth, which allows the reader to see ever-changing Russia as an integrated whole.” —DMITRI TRENIN, senior associate and deputy director of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace’s Moscow Center “In a series of essays that range from the war in Chechnya to the res- taurant scene in the new Moscow, Leon Aron proves himself to be an exceptional guide to Russia’s transformation. His essays are sharp, opinionated, at times provocative, and always a good read. They emphasize the progress that Russia has made despite the ups and downs of the last fifteen years and remind us that Russia’s revolution is far from finished.” —TIMOTHY FRYE, professor of political science, Columbia University RUSSIA’S REVOLUTION RUSSIA’S REVOLUTION Essays 1989–2006 Leon Aron The AEI Press Publisher for the American Enterprise Institute WASHINGTON, D.C.