CHANGE in the BY-NAMES and SURNAMES of the COTSWOLDS, 1381 to C1600 DAVID HARRY PARKIN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ancient Mesopotamian Place Name “Meluḫḫa”

THE ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIAN PLACE NAME “meluḫḫa” Stephan Hillyer Levitt INTRODUCTION The location of the Ancient Mesopotamian place name “Meluḫḫa” has proved to be difficult to determine. Most modern scholars assume it to be the area we associate with Indus Valley Civilization, now including the so-called Kulli culture of mountainous southern Baluchistan. As far as a possible place at which Meluḫḫa might have begun with an approach from the west, Sutkagen-dor in the Dasht valley is probably as good a place as any to suggest (Possehl 1996: 136–138; for map see 134, fig. 1). Leemans argued that Meluḫḫa was an area beyond Magan, and was to be identified with the Sind and coastal regions of Western India, including probably Gujarat. Magan he identified first with southeast Arabia (Oman), but later with both the Arabian and Persian sides of the Gulf of Oman, thus including the southeast coast of Iran, the area now known as Makran (1960a: 9, 162, 164; 1960b: 29; 1968: 219, 224, 226). Hansman identifies Meluḫḫa, on the basis of references to products of Meluḫḫa being brought down from the mountains, as eastern Baluchistan in what is today Pakistan. There are no mountains in the Indus plain that in its southern extent is Sind. Eastern Baluchistan, on the other hand, is marked throughout its southern and central parts by trellised ridges that run parallel to the western edge of the Indus plain (1973: 559–560; see map [=fig. 1] facing 554). Thapar argues that it is unlikely that a single name would refer to the entire area of a civilization as varied and widespread as Indus Valley Civilization. -

March 21, 2005, 3:30 – 5:00 P.M

CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY Faculty Senate Meeting of March 21, 2005, 3:30 – 5:00 p.m. Toepfer Room, Adelbert Hall AGENDA 3:30 1. Approval of the Minutes of the Meeting of March 1, 2005 B. Carlsson 3:35 2. President’s Announcements E. Hundert 3:45 3. Provost’s Announcements J. Anderson 3:55 4. Chair’s Announcements B. Carlsson 4:00 5. Report of the Executive Committee E. Madigan 4:05 6. Report of the Faculty Personnel Committee A. Huckelbridge MOTIONS to Approve Both Proposals - Proposal on Joint Faculty Appointments - Policy on Consensual Relationships 4:20 7. Report of the Information Resources Committee E. Madigan 4:25 8. Report of the By-Laws Committee: G. Narsavage Status of By-Laws by Schools 4:30 9. Ohio Senate Bill: How to Respond R. Wright 4:45 10. Role of the Senate: B. Carlsson Communication Between Senators and their Faculty 11. Other Business 5:00 12. MOTION to Adjourn CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY Faculty Senate Meeting of March 21, 2005, 3:30 – 5:00 p.m. Toepfer Room, Adelbert Hall Minutes Members Attending James Alexander Edward Hundert Spencer Neth John Anderson Kimberly Hyde Theresa Pretlow Hussein Assaf Patrick Kennedy John Protasiewicz Bo Carlsson Carolyn Kercsmar Robert Salata Sayan Chatterjee George Kikano Paul Salipante Francis Curd Joseph Koonce Laura Siminoff Sara Debanne Kenneth Ledford David Singer Kathleen Farkas Edith Lerner Ryan Starks Lynne Ford Alan Levine Aloen Townsend Paul Gerhart Kenneth Loparo Constance Visovsky Stanton Gerson Elizabeth Madigan E. Ronald Wright Katherine Hessler David Matthiesen Arthur Huckelbridge Georgia Narsavage Others Present Christine Ash Robin Kramer Margaret Robinson Joanne Eustis Laura Massie Charles Rozek G. -

Surnames in Europe

DOI: http://dx.doi.org./10.17651/ONOMAST.61.1.9 JUSTYNA B. WALKOWIAK Onomastica LXI/1, 2017 Uniwersytet im. Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu PL ISSN 0078-4648 [email protected] FUNCTION WORDS IN SURNAMES — “ALIEN BODIES” IN ANTHROPONYMY (WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO POLAND) K e y w o r d s: multipart surnames, compound surnames, complex surnames, nobiliary particles, function words in surnames INTRODUCTION Surnames in Europe (and in those countries outside Europe whose surnaming patterns have been influenced by European traditions) are mostly conceptualised as single entities, genetically nominal or adjectival. Even if a person bears two or more surnames, they are treated on a par, which may be further emphasized by hyphenation, yielding the phenomenon known as double-barrelled (or even multi-barrelled) surnames. However, this single-entity approach, visible e.g. in official forms, is largely an oversimplification. This becomes more obvious when one remembers such household names as Ludwig van Beethoven, Alexander von Humboldt, Oscar de la Renta, or Olivia de Havilland. Contemporary surnames resulted from long and complicated historical processes. Consequently, certain surnames contain also function words — “alien bodies” in the realm of proper names, in a manner of speaking. Among these words one can distinguish: — prepositions, such as the Portuguese de; Swedish von, af; Dutch bij, onder, ten, ter, van; Italian d’, de, di; German von, zu, etc.; — articles, e.g. Dutch de, het, ’t; Italian l’, la, le, lo — they will interest us here only when used in combination with another category, such as prepositions; — combinations of prepositions and articles/conjunctions, or the contracted forms that evolved from such combinations, such as the Italian del, dello, del- la, dell’, dei, degli, delle; Dutch van de, van der, von der; German von und zu; Portuguese do, dos, da, das; — conjunctions, e.g. -

BLEDINGTON FOXHOLES and FOSCOT NEWS March 2021 No 444

1 BLEDINGTON FOXHOLES AND FOSCOT NEWS March 2021 No 444 Wandering amongst the tens of thousands of snowdrops at Colesbourne Park with the blue coloured water in the lake reflecting the clay minerals in the water. 2 DATES FOR YOUR DIARY MARCH 2021 Mondays and Fridays; Post Office, Oddington Vill. Hall (p 3) 10.30 to 12.00 Monday 1 Foxholes/Foscot WODC Grey Collection Day (p 17) 6.00am Monday 1 Bledington Parish Council Meeting (ZOOM) (p 12) 8.00pm Tuesday 2 Bledington CDC Recycling Day (p 17) 7.00am Monday 8 Foxholes/Foscot WODC Green Collection Day (p 17) 6.00am Wednesday 10 Egyptian Art, Walls and Murals (p 13) 10.30am Monday 15 Foxholes/Foscot Grey Collection Day (p 17) 6.00am Tuesday 16 Bledington CDC Recycling Day (p 17) 7.00am Wednesday 17 Music in European Art Collections (p 13) 10.30am Monday 22 Foxholes/Foscot WODC Green Collection Day (p 17) 6.00am Tuesday 23 BLEDINGTON NEWS COPY DEADLINE (p 2) 12.00noon Sunday 28 CLOCKS GO FORWARD ONE HOUR 1.00am WE WELCOME NEWS CONTRIBUTIONS TO BLEDINGTON, FOXHOLES AND FOSCOT NEWS Please send your news contributions for the next Issue at any time. Copy deadline is strictly 12.00 Noon 23rd of each month (January to November). Please send news contributions for Bledington News to the editors, Wendy and Sinclair Scott, by paper copy to 4 Old Forge Close, Bledington, Chipping Norton, OX7 6XW or email us at [email protected] Tel: 01608 658624. Bledington News is published in full colour at www.bledington.com Please ensure you have a prompt acknowledgement of your contribution sent by email; this makes it certain we have received it. -

Bramwell, Ellen S. (2012) Naming in Society: a Cross-Cultural Study of Five Communities in Scotland

Bramwell, Ellen S. (2012) Naming in society: a cross-cultural study of five communities in Scotland. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/3173/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ENGLISH LANGUAGE, COLLEGE OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW Naming in Society A cross-cultural study of five communities in Scotland Ellen Sage Bramwell September 2011 © Ellen S. Bramwell 2011 Abstract Personal names are a human universal, but systems of naming vary across cultures. While a person’s name identifies them immediately with a particular cultural background, this aspect of identity is rarely researched in a systematic way. This thesis examines naming patterns as a product of the society in which they are used. Personal names have been studied within separate disciplines, but to date there has been little intersection between them. This study marries approaches from anthropology and linguistic research to provide a more comprehensive approach to name-study. Specifically, this is a cross-cultural study of the naming practices of several diverse communities in Scotland, United Kingdom. -

Secondary School and Academy Admissions

Secondary School and Academy Admissions INFORMATION BOOKLET 2021/2022 For children born between 1st September 2009 and 31st August 2010 Page 1 Schools Information Admission number and previous applications This is the total number of pupils that the school can admit into Year 7. We have also included the total number of pupils in the school so you can gauge its size. You’ll see how oversubscribed a school is by how many parents had named a school as one of their five preferences on their application form and how many of these had placed it as their first preference. Catchment area Some comprehensive schools have a catchment area consisting of parishes, district or county boundaries. Some schools will give priority for admission to those children living within their catchment area. If you live in Gloucestershire and are over 3 miles from your child’s catchment school they may be entitled to school transport provided by the Local Authority. Oversubscription criteria If a school receives more preferences than places available, the admission authority will place all children in the order in which they could be considered for a place. This will strictly follow the priority order of their oversubscription criteria. Please follow the below link to find the statistics for how many pupils were allocated under the admissions criteria for each school - https://www.gloucestershire.gov.uk/education-and-learning/school-admissions-scheme-criteria- and-protocol/allocation-day-statistics-for-gloucestershire-schools/. We can’t guarantee your child will be offered one of their preferred schools, but they will have a stronger chance if they meet higher priorities in the criteria. -

Stroud Labour Party

Gloucestershire County Council single member ward review Response from Stroud Constituency Labour Party Introduction On 30 November the Local Government Boundary Commission started its second period of consultation for a pattern of divisions for Gloucestershire. Between 30 November and 21 February the Commission is inviting comments on the division boundaries for GCC. Following the completion of its initial consultation, the Commission has proposed that the number of county councillors should be reduced from 63 to 53. The districts have provided the estimated numbers for the electorate in their areas in 2016; the total number for the county is 490,674 so that the average electorate per councillor would be 9258 (cf. 7431 in 2010). The main purpose of this note is to draw attention to the constraints imposed on proposals for a new pattern of divisions in Stroud district, which could lead to anomalies, particularly in ‘bolting together’ dissimilar district wards and parishes in order to meet purely numerical constraints. In it own words ‘the Commission aims to recommend a pattern of divisions that achieves good electoral equality, reflects community identities and interests and provides for effective and convenient local government. It will also seek to use strong, easily-identifiable boundaries. ‘Proposals should demonstrate how any pattern of divisions aids the provision of effective and convenient local government and why any deterioration in equality of representation or community identity should be accepted. Representations that are supported by evidence and argument will carry more weight with the Commission than those which merely assert a point of view.’ While a new pattern of ten county council divisions is suggested in this note, it is not regarded as definitive but does contain ways of avoiding some possible major anomalies. -

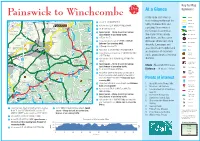

Painswick to Winchcombe Cycle Route

Great Comberton A4184 Elmley Castle B4035 Netherton B4632 B4081 Hinton on the Green Kersoe A38 CHIPPING CAMPDEN A46(T) Aston Somerville Uckinghall Broadway Ashton under Hill Kemerton A438 (T) M50 B4081 Wormington B4479 Laverton B4080 Beckford Blockley Ashchurch B4078 for Tewkesbury Bushley B4079 Great Washbourne Stanton A38 A38 Key to Map A417 TEWKESBURY A438 Alderton Snowshill Day A438 Bourton-on-the-Hill Symbols: B4079 A44 At a Glance M5 Teddington B4632 4 Stanway M50 B4208 Dymock Painswick to WinchcombeA424 Linkend Oxenton Didbrook A435 PH A hilly route from start to A Road Dixton Gretton Cutsdean Hailes B Road Kempley Deerhurst PH finish taking you through the Corse Ford 6 At fork TL SP BRIMPSFIELD. B4213 B4211 B4213 PH Gotherington Minor Road Tredington WINCHCOMBE Farmcote rolling Cotswold hills and Tirley PH 7 At T junctionB4077 TL SP BIRDLIP/CHELTENHAM. Botloe’s Green Apperley 6 7 8 9 10 Condicote Motorway Bishop’s Cleeve PH Several capturing the essence of Temple8 GuitingTR SP CIRENCESTER. Hardwicke 22 Lower Apperley Built-up Area Upleadon Haseld Coombe Hill the Cotswold countryside. Kineton9 Speed aware – Steep descent on narrow B4221 River Severn Orchard Nook PH Roundabouts A417 Gorsley A417 21 lane. Beware of oncoming traffic. The route follows mainly Newent A436 Kilcot A4091 Southam Barton Hartpury Ashleworth Boddington 10 At T junction TL. Lower Swell quiet lanes, and has some Railway Stations B4224 PH Guiting Power PH Charlton Abbots PH11 Cross over A 435 road SP UPPER COBERLEY. strenuous climbs and steep B4216 Prestbury Railway Lines Highleadon Extreme Care crossing A435. Aston Crews Staverton Hawling PH Upper Slaughter descents. -

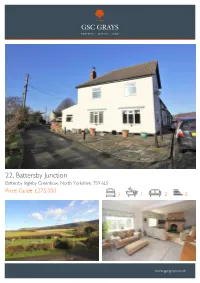

Vebraalto.Com

22, Battersby Junction Battersby Ingleby Greenhow, North Yorkshire, TS9 6LS Price Guide £275,000 3 1 2 E 22, Battersby Junction Battersby Ingleby Greenhow, North Yorkshire TS9 6LS Price Guide £275,000 Location and opens up to the kitchen. The kitchen has a range of Northallerton 20.7 miles, Yarm 14.6 miles, Middlesbrough floor and wall mounted units, glass display cases, fitted 12.4 miles, Darlington 26.2 miles (distances are fridge and freezer, built-in double oven, four ring electric approximate). Excellent road links to the A19, A66 and A1 halogen hob, Belfast-style sink with granite draining unit, providing access to Teesside, Newcastle, Durham, York, part tiled walls and windows enjoying views towards the Harrogate and Leeds. Direct train services from Cleveland Hills and Wainstones. Opens up to a rear hallway, Northallerton and Darlington to London Kings Cross, with door to the utility room, floor-to-ceiling cupboards Manchester and Edinburgh. International Airports: Durham and door leading outside. Tees Valley, Newcastle and Leeds Bradford. Utility Room 7'4" x 6'6" (2.23 x 1.99) Amenities With storage cupboards, low-level w.c, plumbing for a Battersby Junction is a small hamlet close to the village of washing machine, fitted sink, tiled splash areas, oil fired Ingleby Greenhow, much sought-after by keen walkers, central heating boiler and frosted window to the rear. horse riders and those seeking a typical North Yorkshire village. Ingleby Greenhow has its own country pub, The First Floor Landing Dudley Arms, a primary school, village hall, cricket club and With loft access and doors to all first floor rooms. -

Police and Crime Commissioner Election Number of Seats Division

Election of Police and Crime Commission for PCC Local Area Police and Crime Commissioner Election Number of Seats Gloucestershire Police Area 1 Election of County Councillors to Gloucestershire County Council Division Number of Division Number of Seats Seats Bisley & Painswick 1 Nailsworth 1 Cam Valley 1 Rodborough 1 Dursley 1 Stroud Central 1 Hardwicke & Severn 1 Stonehouse 1 Minchinhampton 1 Wotton-under-Edge 1 TOTAL 10 Election of District Councillors to Stroud District Council District Council Number of District Council Election Seats Election Amberley & Woodchester 1 Randwick, Whiteshill & 1 Ruscombe Berkeley Vale 3 Rodborough 2 Bisley 1 Severn 2 Cainscross 3 Stonehouse 3 Cam East 2 Stroud Central 1 Cam West 2 Stroud Farmhill & Paganhill 1 Chalford 3 Stroud Slade 1 Coaley & Uley 1 Stroud Trinity 1 Dursley 3 Stroud Uplands 1 Hardwicke 3 Stroud Valley 1 Kingswood 1 The Stanley 2 Minchinhampton 2 Thrupp 1 Nailsworth 3 Wotton-under-Edge 3 Painswick & Upton 3 TOTAL 51 Election of Parish/Town Councillors to [name of Parish/Town] Council. Parish/Town Number of Parish/Town Number of Council/Ward Seats Council/Ward seats Minchinhampton (Amberley Alkington 7 Ward) 2 Minchinhampton (Box Arlingham 7 Ward) 1 Minchinhampton Berkeley 9 (Brimscombe Ward) 3 Minchinhampton (North Bisley (Bisley Ward) 4 Ward) 6 Minchinhampton (South Bisley (Eastcombe Ward) 4 Ward) 3 Bisley (Oakridge Ward) 4 Miserden 5 Brookthorpe-with-Whaddon 6 Moreton Valence 5 Cainscross (Cainscross Ward) 2 Nailsworth 11 Cainscross (Cashes Green East Ward) 3 North Nibley 7 Cainscross -

Early Medieval Oxfordshire

Anglo-Saxon Oxfordshire Sally Crawford and Anne Dodd, December 2007 1. Introduction: nature of the evidence, history of research and the role of material culture Anglo-Saxon Oxfordshire has been extremely well served by archaeological research, not least because of coincidence of Oxfordshire’s diverse underlying geology and the presence of the University of Oxford. Successive generations of geologists at Oxford studied and analysed the landscape of Oxfordshire, and in so doing, laid the foundations for the new discipline of archaeology. As early as 1677, geologist Robert Plot had published his The Natural History of Oxfordshire ; William Smith (1769- 1839), who was born in Churchill, Oxfordshire, determined the law of superposition of strata, and in so doing formulated the principles of stratigraphy used by archaeologists and geologists alike; and William Buckland (1784-1856) conducted experimental archaeology on mammoth bones, and recognised the first human prehistoric skeleton. Antiquarian interest in Oxfordshire lead to a number of significant discoveries: John Akerman and Stephen Stone's researches in the gravels at Standlake recorded Anglo-Saxon graves, and Stone also recognised and plotted cropmarks in his local area from the back of his horse (Akerman and Stone 1858; Stone 1859; Brown 1973). Although Oxford did not have an undergraduate degree in Archaeology until the 1990s, the Oxford University Archaeological Society, originally the Oxford University Brass Rubbing Society, was founded in the 1890s, and was responsible for a large number of small but significant excavations in and around Oxfordshire as well as providing a training ground for many British archaeologists. Pioneering work in aerial photography was carried out on the Oxfordshire gravels by Major Allen in the 1930s, and Edwin Thurlow Leeds, based at the Ashmolean Museum, carried out excavations at Sutton Courtenay, identifying Anglo-Saxon settlement in the 1920s, and at Abingdon, identifying a major early Anglo-Saxon cemetery (Leeds 1923, 1927, 1947; Leeds 1936). -

Deadly Hostility: Feud, Violence, and Power in Early Anglo-Saxon England

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 6-2017 Deadly Hostility: Feud, Violence, and Power in Early Anglo-Saxon England David DiTucci Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation DiTucci, David, "Deadly Hostility: Feud, Violence, and Power in Early Anglo-Saxon England" (2017). Dissertations. 3138. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/3138 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEADLY HOSTILITY: FEUD, VIOLENCE, AND POWER IN EARLY ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND by David DiTucci A dissertation submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy History Western Michigan University June 2017 Doctoral Committee: Robert F. Berkhofer III, Ph.D., Chair Jana Schulman, Ph.D. James Palmitessa, Ph.D. E. Rozanne Elder, Ph.D. DEADLY HOSTILITY: FEUD, VIOLENCE, AND POWER IN EARLY ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND David DiTucci, Ph.D. Western Michigan University, 2017 This dissertation examines the existence and political relevance of feud in Anglo-Saxon England from the fifth century migration to the opening of the Viking Age in 793. The central argument is that feud was a method that Anglo-Saxons used to understand and settle conflict, and that it was a tool kings used to enhance their power. The first part of this study examines the use of fæhð in Old English documents, including laws and Beowulf, to demonstrate that fæhð referred to feuds between parties marked by reciprocal acts of retaliation.