Download Discharging to Atmosphere from Laboratory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Computer Simulations and the Trading Zone

PETER &A Computer Simulations and the Trading Zone At the root of most accounts of the development of science is the covert premise that science is about ontology: What objects are there? How do they interact? And how do we discover them? It is a premise that underlies three distinct epochs of inquiry into the nature of science. Among the positivists, the later Carnap explicitly advocated a view that the objects of physics would be irretrievably bound up with what he called a "framework," a full set of linguistic relations such as is found in Newtonian or Eiustcini;~mechanics. That these frameworks held little in common did not trouble Car- nap; prediction mattered more than progress. Kuhn molded this notion and gave it a more historical focus. Unlike the positivists, Kuhn and other commentators of the 1960's wanted to track the process by which a community abandoned one framework and adopted another. To more recent scholars, the Kuhnian categoriza- tion of group affiliation and disaffiliation was by and large correct, but its underlying dynamics were deemed deficient because they paid insufficient attention to the sociological forces that bound groups to their paradigms. All three generations embody the root assumption that the analysis of science studies (or ought to study) a science classified and divided according to the objects of its inquiry. All three assume that as these objects change, particular branches of science split into myriad disconnected parts. It is a view of scientific disunity that I will refer to as "framework relativism. 55 In this essay, as before, I will oppose this view, but not by Computer Simulations I 19 invoking the old positivist pipe dreams: no universal protocol languages, no physicalism, no Corntian hierarchy of knowledge, and no radical reductionism. -

The Real Holocaust

THE REAL HOLOCAUST "Hitler will have no war, but he will be forced into it, not this year but later..." Emil Ludwig [Jew], Les Annales, June 1934 "We possess several hundred atomic warheads and rockets and can launch them at targets in all directions, perhaps even at Rome. Most European capitals are targets for our air force. Let me quote General Moshe Dayan: 'Israel must be like a mad dog, too dangerous to bother.' I consider it all hopeless at this point. We shall have to try to prevent things from coming to that, if at all possible. Our armed forces, however, are not the thirtieth strongest in the world, but rather the second or third. We have the capability to take the world down with us. And I can assure you that that will happen before Israel goes under." -- Martin van Creveld, Israeli professor of military history at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem in an interview in the Dutch weekly magazine: Elsevier, 2002, no. 17, p. 52-53. "We may never actually have to use this atomic weapon in military operations as the mere threat of its use will persuade any opponent to surrender to us." –Chaim Weizmann [Jew] "Jews Declared War on Germany. Even before the war started, the Jewish leaders on a worldwide basis had years before, declared that world Jewry was at war with Germany, and that they would utilize their immense financial, moral, and political powers to destroy Hitler and Nazi Germany. Principal among these was Chaim Weizmann, the Zionist leader, who so declared on September 5, 1939. -

Monte Carlo Simulation Techniques

Monte Carlo Simulation Techniques Ji Qiang Accelerator Modeling Program Accelerator Technology & Applied Physics Division Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory CERN Accelerator School, Thessaloniki, Greece Nov. 13, 2018 Introduction: What is the Monte Carlo Method? • What is the Monte Carlo method? - Monte Carlo method is a (computational) method that relies on the use of random sampling and probability statistics to obtain numerical results for solving deterministic or probabilistic problems “…a method of solving various problems in computational mathematics by constructing for each problem a random process with parameters equal to the required quantities of that problem. The unknowns are determined approximately by carrying out observations on the random process and by computing its statistical characteristics which are approximately equal to the required parameters.” J. H. Halton, “A retrospective and prospective survey of the Monte Carlo Method,” SIAM Review, Vol. 12, No. 1 (1970). Introduction: What can the Monte Carlo Method Do? • Give an approximate solution to a problem that is too big, too hard, too irregular for deterministic mathematical approach • Two types of applications: a) The problems that are stochastic (probabilistic) by nature: - particle transport, - telephone and other communication systems, - population studies based on the statistics of survival and reproduction. b) The problems that are deterministic by nature: - the evaluation of integrals, - solving partial differential equations • It has been used in areas as diverse as physics, chemistry, material science, economics, flow of traffic and many others. Brief History of the Monte Carlo Method • 1772 Comte de Buffon - earliest documented use of random sampling to solve a mathematical problem (the probability of needle crossing parallel lines). -

Berni Alder (1925–2020)

Obituary Berni Alder (1925–2020) Theoretical physicist who pioneered the computer modelling of matter. erni Alder pioneered computer sim- undergo a transition from liquid to solid. Since LLNL ulation, in particular of the dynamics hard spheres do not have attractive interac- of atoms and molecules in condensed tions, freezing maximizes their entropy rather matter. To answer fundamental ques- than minimizing their energy; the regular tions, he encouraged the view that arrangement of spheres in a crystal allows more Bcomputer simulation was a new way of doing space for them to move than does a liquid. science, one that could connect theory with A second advance concerned how non- experiment. Alder’s vision transformed the equilibrium fluids approach equilibrium: field of statistical mechanics and many other Albert Einstein, for example, assumed that areas of applied science. fluctuations in their properties would quickly Alder, who died on 7 September aged 95, decay. In 1970, Alder and Wainwright dis- was born in Duisburg, Germany. In 1933, as covered that this intuitive assumption was the Nazis came to power, his family moved to incorrect. If a sphere is given an initial push, Zurich, Switzerland, and in 1941 to the United its average velocity is found to decay much States. After wartime service in the US Navy, more slowly. This caused a re-examination of Alder obtained undergraduate and master’s the microscopic basis for hydrodynamics. degrees in chemistry from the University of Alder extended the reach of simulation. California, Berkeley. While working for a PhD In molecular dynamics, the forces between at the California Institute of Technology in molecules arise from the electronic density; Pasadena, under the physical chemist John these forces can be described only by quan- Kirkwood, he began to use mechanical com- tum mechanics. -

Oral History Interview with Nicolas C. Metropolis

An Interview with NICOLAS C. METROPOLIS OH 135 Conducted by William Aspray on 29 May 1987 Los Alamos, NM Charles Babbage Institute The Center for the History of Information Processing University of Minnesota, Minneapolis Copyright, Charles Babbage Institute 1 Nicholas C. Metropolis Interview 29 May 1987 Abstract Metropolis, the first director of computing services at Los Alamos National Laboratory, discusses John von Neumann's work in computing. Most of the interview concerns activity at Los Alamos: how von Neumann came to consult at the laboratory; his scientific contacts there, including Metropolis, Robert Richtmyer, and Edward Teller; von Neumann's first hands-on experience with punched card equipment; his contributions to shock-fitting and the implosion problem; interactions between, and comparisons of von Neumann and Enrico Fermi; and the development of Monte Carlo techniques. Other topics include: the relationship between Turing and von Neumann; work on numerical methods for non-linear problems; and the ENIAC calculations done for Los Alamos. 2 NICHOLAS C. METROPOLIS INTERVIEW DATE: 29 May 1987 INTERVIEWER: William Aspray LOCATION: Los Alamos, NM ASPRAY: This is an interview on the 29th of May, 1987 in Los Alamos, New Mexico with Dr. Nicholas Metropolis. Why don't we begin by having you tell me something about when you first met von Neumann and what your relationship with him was over a period of time? METROPOLIS: Well, he first came to Los Alamos on the invitation of Dr. Oppenheimer. I don't remember quite when the date was that he came, but it was rather early on. It may have been the fall of 1943. -

Doing Mathematics on the ENIAC. Von Neumann's and Lehmer's

Doing Mathematics on the ENIAC. Von Neumann's and Lehmer's different visions.∗ Liesbeth De Mol Center for Logic and Philosophy of Science University of Ghent, Blandijnberg 2, 9000 Gent, Belgium [email protected] Abstract In this paper we will study the impact of the computer on math- ematics and its practice from a historical point of view. We will look at what kind of mathematical problems were implemented on early electronic computing machines and how these implementations were perceived. By doing so, we want to stress that the computer was in fact, from its very beginning, conceived as a mathematical instru- ment per se, thus situating the contemporary usage of the computer in mathematics in its proper historical background. We will focus on the work by two computer pioneers: Derrick H. Lehmer and John von Neumann. They were both involved with the ENIAC and had strong opinions about how these new machines might influence (theoretical and applied) mathematics. 1 Introduction The impact of the computer on society can hardly be underestimated: it affects almost every aspect of our lives. This influence is not restricted to ev- eryday activities like booking a hotel or corresponding with friends. Science has been changed dramatically by the computer { both in its form and in ∗The author is currently a postdoctoral research fellow of the Fund for Scientific Re- search { Flanders (FWO) and a fellow of the Kunsthochschule f¨urMedien, K¨oln. 1 its content. Also mathematics did not escape this influence of the computer. In fact, the first computer applications were mathematical in nature, i.e., the first electronic general-purpose computing machines were used to solve or study certain mathematical (applied as well as theoretical) problems. -

Anthony Turkevich

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES ANTHONY LEONID TURKEVICH 1916-2002 A Biographical Memoir by R. STEPHEN BERRY, ROBERT N. CLAYTON, GEORGE A. COWAN, AND THANASIS E. ECONOMOU Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 2007 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON, D.C. ANTHONY L. TURKEVICH July 23, 1916–September 7, 2002 BY R. STEPHEN BERRY, ROBERT N. CLAYTON, GEORGE A. COWAN, AND THANASIS E. ECONOMOU NTHONY LEONID (“TONY”) TURKEVICH WAS born in New York A City in 1916, one of three children of a Russian Ortho- dox clergyman, Leonid Turkevich, who became head of the entire Russian Orthodox Church in North America and Ja- pan. Tony went to Dartmouth College for his undergradu- ate studies, completing his B.A. in 1937. From there he went to Princeton, working with J. Y. Beach on structures of small molecules for his Ph.D., which he received in 1940. Turkevich then went to Robert Mulliken in the Department of Physics at the University of Chicago as a research assis- tant, studying molecular spectroscopy. He also worked on the radiochemistry of fission products. Soon after the outbreak of World War II Tony joined the Manhattan Project as one of its youngest scientists. In 1942 he worked at Columbia and the next year went to the Metallurgical Laboratory at the University of Chicago where he stayed until 1945, when he moved on to Los Alamos. During that period Turkevich worked closely with Charles P. Smyth and Enrico Fermi. -

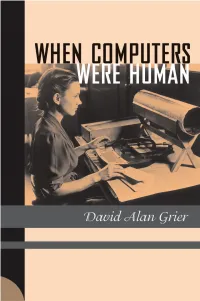

When Computers Were Human

When Computers Were Human When Computers Were Human David Alan Grier princeton university press princeton and oxford Copyright © 2005 by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY All Rights Reserved Third printing, and first paperback printing, 2007 Paperback ISBN: 978-0-691-13382-9 The Library of Congress has cataloged the cloth edition of this book as follows Grier, David Alan, 1955 Feb. 14– When computers were human / David Alan Grier. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-691-09157-9 (acid-free paper) 1. Calculus—History. 2. Science—Mathematics—History. I. Title. QA303.2.G75 2005 510.922—dc22 2004022631 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available This book has been composed in Sabon Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ press.princeton.edu Printed in the United States of America 109876543 FOR JEAN Who took my people to be her people and my stories to be her own without realizing that she would have to accept a comet, the WPA, and the oft-told tale of a forgotten grandmother Contents Introduction A Grandmother’s Secret Life 1 Part I: Astronomy and the Division of Labor 9 1682–1880 Chapter One The First Anticipated Return: Halley’s Comet 1758 11 Chapter Two The Children of Adam Smith 26 Chapter Three The Celestial Factory: Halley’s Comet 1835 46 Chapter Four The American Prime Meridian 55 Chapter Five A Carpet for the Computing Room 72 Part II: -

THE BEGINNING of the MONTE CARLO METHOD by N

THE BEGINNING of the MONTE CARLO METHOD by N. Metropolis he year was 1945. Two earth- Some Background first electronic computer—the ENIAC— shaking events took place: the at the University of Pennsylvania in Phil- successful test at Alamogordo Most of us have grown so blase about adelphia. Their mentors were Physicist and the building of the first elec- computer developments and capabilities First Class John Mauchly and Brilliant tronicT computer. Their combined impact -even some that are spectacular—that Engineer Presper Eckert. Mauchly, fa- was to modify qualitatively the nature of it is difficult to believe or imagine there miliar with Geiger counters in physics global interactions between Russia and was a time when we suffered the noisy, laboratories, had realized that if electronic the West. No less perturbative were the painstakingly slow, electromechanical de- circuits could count, then they could do changes wrought in all of academic re- vices that chomped away on punched arithmetic and hence solve, inter alia, dif- search and in applied science. On a less cards. Their saving grace was that they ference equations—at almost incredible grand scale these events brought about a continued working around the clock, ex- speeds! When he’d seen a seemingly renascence of a mathematical technique cept for maintenance and occasional re- limitless array of women cranking out known to the old guard as statistical sam- pair (such as removing a dust particle firing tables with desk calculators, he’d pling; in its new surroundings and owing from a relay gap). But these machines been inspired to propose to the Ballistics to its nature, there was no denying its new helped enormously with the routine, rela- Research Laboratory at Aberdeen that an name of the Monte Carlo method. -

Oral History of Akrevoe Emmanouilides, 2008-08-19

Oral History of Akrevoe Emmanouilides Interviewed by: Dag Spicer Recorded: August 19, 2008 Mountain View, California CHM Reference number: X4980.2009 © 2008 Computer History Museum Oral History of Akrevoe Emmanouilides Dag Spicer: Welcome. We're here today. I'm Dag Spicer with the Computer History Museum. I'm here with Akrevoe Emmanou— Akrevoe Emmanouilides: Emmanouilides. Spicer: Emmanouilides. And could you just spell that for us so we have it on camera? Emmanouilides: Of course. My first name is A-k-r-e-v-o-e. My last name is E-m-m-a-n-o-u-i-l-i-d-e-s. And Akrevoe is the Greek word for expensive or precious, and Emmanouilides means the son of Emmanuel. Spicer: So that's a great name, great combination. Thanks for being with us today. I really appreciate that, and especially, you coming to visit us just kind of on a lark last week. You just came by to say hello and we met, and it turned out that you actually were present at some very important times in computer history. And before we get to those, I thought we'd just start out with your early childhood and where you grew up and maybe a bit about your parents and your schooling. Why don't we just start there? Emmanouilides: Fine. I was born in Philadelphia in 1928, September 11th, <laugh> coincidentally, which has become a very important day in our own history. I was raised in Philadelphia. My parents were immigrants; my father from the Ionian island of Lefkas, which is on the western coast of Greece, and my mother was from Turkey, from an area called Marmara. -

People of the Hill—The Early Days

Inspiration from the Past 2 Los Alamos Science Number 28 2003 Number 28 2003 Los Alamos Science 3 People of the Hill Preface In the first decade of its existence, 1943 to 1953, the Los Alamos Laboratory developed the fission weapon and the thermonuclear fusion weapon, popularly known as the atomic bomb and the hydrogen bomb. This memoir of that early period is one person’s viewpoint, the view of a man now over 80 years old, looking back on a golden time when he first arrived in Los Alamos with his new bride in March 1947. It is my recall, seasoned with the knowledge of a lifetime, of a new town and a new laboratory. Most of the scientists in this story were known to me personally. Others, I knew through the eyes of my young close friends. But my knowledge is only that of a student, blooming into scholarship in the presence of some of the master scientists of the era. That there is wonder and worship is no accident; these are my personal impres- sions, not the complete view of a skilled biographer. Of course, these people are far more complex than revealed to me by the professor-student relation. Also, I have stayed entirely within the period of that first decade, before the Oppenheimer security investigation, which polarized the scientific community and profoundly altered its rela- tionships. I have not permitted that tragic affair to rewrite the sentiments of the earlier time. So this account is not meant to be history’s dispassionate catalog of events. -

Experimental and Mathematical Modeling Studies on Current Distribution in High Temperature Superconducting DC Cables Venkata Pothavajhala

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2014 Experimental and Mathematical Modeling Studies on Current Distribution in High Temperature Superconducting DC Cables Venkata Pothavajhala Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING EXPERIMENTAL AND MATHEMATICAL MODELING STUDIES ON CURRENT DISTRIBUTION IN HIGH TEMPERATURE SUPERCONDUCTING DC CABLES By VENKATA POTHAVAJHALA A Thesis submitted to the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2014 Venkata Pothavajhala defended this thesis on June 24, 2014. The members of the supervisory committee were: Chris Edrington Professor Directing Thesis Lukas Graber Committee Member Petru Andrei Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii I dedicate this work to my parents and to my research supervisor iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like thank Professor Chris S. Edrington for being an excellent academic advisor and guiding me through the MS program and helping me choose my course work and planning my research. I would like to express my deepest appreciation and sincere gratitude to my research supervisor Dr. Sastry Pamidi for providing me the opportunity to work under his guidance and for his continuous support throughout my research. It is a pleasure working under such a great scientist. I’m thankful to him for spending the time for our weekly discussions though he is very busy with other projects, proposals and meetings.