Program Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yhtenäistetty Gabriel Fauré : Teosten Yhtenäistettyjen Nimekkeiden Ohjeluettelo / Heikki Poroila

Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistyksen julkaisusarja 108 Yhtenäistetty Gabriel Fauré Teosten yhtenäistettyjen nimekkeiden ohjeluettelo Heikki Poroila Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistys Helsinki 2012 Julkaisija Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistys ry Ulkoasu Heikki Poroila © Heikki Poroila 2012 Toinen laitos, verkkoversio 2.0 01.4 Poroila, Heikki Yhtenäistetty Gabriel Fauré : Teosten yhtenäistettyjen nimekkeiden ohjeluettelo / Heikki Poroila. – Toinen laitos, verkkoversio 2.0. – Helsinki : Suomen musiikkikirjas- toyhdistys, 2012. – 19 s. – (Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistyksen julkaisusarja, ISSN 0784-0322 ; 108) – ISBN 952-5363-07-4 (PDF) ISBN 952-5363-07-4 (PDF) Yhtenäistetty Gabriel Fauré 2 Luettelon käyttäjälle GABRIEL FAURÉ (1845 – 1924) ei ole kirjastodokumentoinnin näkökulmasta erityisen hankala sävel- täjä. Useiden sävellysten pysyvä suosio antaa kuitenkin aihetta koko tuotannon standardointiin. Varsinaista teosluetteloa ei ole olemassa, vaan tiedot pohjautuvat keskeisissä hakuteoksissa oleviin luetteloihin. Pääosa Faurén sävellyksistä on opusnumeroituja, numerottomia on vain muutama kymmenen, nekin pääosin vähemmän tunnettuja teoksia. Opusnumerolistassa näyttäisi puuttuvan muutamia numeroita (9, 53, 60, 64, 71, 81, 100), joita ei ole ainakaan toistaiseksi löytynyt. Helsingin Viikissä lokakuussa 2012 Heikki Poroila Yhtenäistetty Gabriel Fauré 3 Opusnumeroidut teokset [Le papillon et la fleur, op1, nro 1] ► 1861. Lauluääni ja piano. Teksti Victor Hugo. ■ La pauvre fleur disait au papillon céleste [Mai, op1, nro 2] ► 1862. Lauluääni ja piano. Teksti Victor Hugo. ■ Puis-que Mai tout en fleurs dans les prés nous réclame [Dans les ruines d’une abbaye, op2, nro 1] ► 1866. Lauluääni ja piano. Teksti Victor Hugo. ■ Seuls, tous deux, ravis, chantants,comme on s’aime [Les matelots, op2, nro 2] ► 1870. Lauluääni ja piano. Teksti Théophile Gautier. ■ Sur l’eau bleue et profonde [Seule!, op3, nro 1] ► 1870. Lauluääni ja piano. Teksti Théophile Gautier. ■ Dans un baiser, l’onde au ravage dit ses douleurs [Sérénade toscane, op3, nro 2] ► 1878. -

Bizet – L' Arlésienne

BIZET – L’ ARLÉSIENNE Fauré – Masques et Bergamasques Gounod – Faust Ballet Music HY BRID MU Orchestre de la Suisse Romande LTICHANNEL Kazuki Yamada Georges Bizet (1838-1875) Charles Gounod (1818-1893) THEATRE MUSIC IN THE always had to be connected to the content L’Arlésienne Faust Ballet Music CONCERT HALL of the drama it preceded, and to introduce the work’s protagonists through musical Suite No. 1 13. Les Nubiennes, valse (Allegretto) 2. 47 When we consider the intrinsic bond means. “It must moreover concern 14. Adagio 4. 34 between theatre and music, though opera itself with the entire play, while at the 1. Prélude 6. 50 15. Danse Antique (Allegretto) 1. 47 and ballet are what immediately come to same time preparing its beginning, and, 2. Minuetto 3. 06 16. Variations de Cléopâtre (Moderato mind, there is yet another art form that correspondingly, also serving as an 3. Adagietto 3. 58 maestoso) 1. 44 embodies this association, and which appropriate introduction to the play’s 4. Carillon 4. 48 17. Les Troyennes (Moderato) 2. 56 especially in the 19th century enjoyed initial entrances.” The entr’actes should, 18. Variations du Miroir (Allegretto) 2. 05 great popularity: incidental music. In a according to Scheibe, “address both the Suite No. 2 19. Danse de Phryné (Allegro vivo) 2. 46 period in which all theatres had either a close of the preceding act, and the start Arranged by Ernest Guiraud pianist or a smaller or larger orchestra in of the following one. I.e., these interludes Total playing time: 69. 56 their employ, stage plays were generally must connect both acts with one another, 5. -

FAURÉ MASQUES ET BERGAMASQUES PELLÉAS ET MÉLISANDE DOLLY | PAVANE FANTAISIE | BERCEUSE | ÉLÉGIE GABRIEL FAURÉ Masques Et Bergamasques Ouverture

SEATTLE SYMPHONY SYMPHONY LUDOVIC MORLOT LUDOVIC FAURÉ MASQUES ET BERGAMASQUES PELLÉAS ET MÉLISANDE DOLLY | PAVANE FANTAISIE | BERCEUSE | ÉLÉGIE GABRIEL FAURÉ Masques et bergamasques Ouverture .............................................................................. 3:47 Menuet ................................................................................... 3:02 Gavotte .................................................................................. 3:24 Pastorale ............................................................................... 3:27 Fantaisie for Flute / orch. Talmi ...................................... 5:27 Demarre McGill, flute Pelléas et Mélisande Suite Prélude ................................................................................... 6:22 Fileuse .....................................................................................2:19 Sicilienne ................................................................................3:51 La mort de Mélisande ......................................................... 5:44 Berceuse for Violin and Orchestra .................................4:13 Alexander Velinzon, violin Élégie for Cello and Orchestra ...................................... 6:57 Efe Baltacıgil, cello Dolly / orch. Rabaud Berceuse ................................................................................ 2:25 Mi-a-ou....................................................................................2:16 Le jardin de Dolly ................................................................. 2:34 -

Masques Et Bergamasques by Gabriel Faur Wind Decet Double Quintet Sheet Music

Masques Et Bergamasques By Gabriel Faur Wind Decet Double Quintet Sheet Music Download masques et bergamasques by gabriel faur wind decet double quintet sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 6 pages partial preview of masques et bergamasques by gabriel faur wind decet double quintet sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 4610 times and last read at 2021-10-01 19:26:14. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of masques et bergamasques by gabriel faur wind decet double quintet you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Ensemble: Woodwind Quintet Level: Intermediate [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Faur Masques Et Bergamasques Suite Op 112 Symphonic Wind Faur Masques Et Bergamasques Suite Op 112 Symphonic Wind sheet music has been read 3213 times. Faur masques et bergamasques suite op 112 symphonic wind arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-10-02 03:43:16. [ Read More ] Faure Masques Et Bergamasques Op 112 Mvt Ii Menuet Wind Dectet Faure Masques Et Bergamasques Op 112 Mvt Ii Menuet Wind Dectet sheet music has been read 3752 times. Faure masques et bergamasques op 112 mvt ii menuet wind dectet arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-10-02 03:48:24. [ Read More ] Faure Masques Et Bergamasques Mvt Iv Pastorale Wind Dectet Faure Masques Et Bergamasques Mvt Iv Pastorale Wind Dectet sheet music has been read 3367 times. -

Bizet – L' Arlésienne

Bizet – L’ ArLésienne Fauré – Masques et Bergamasques Gounod – Faust Ballet Music Orchestre de la Suisse Romande Kazuki Yamada Georges Bizet (1838-1875) L’Arlésienne tHeAtre MUsiC in tHe COnCERT HALL Suite No. 1 When we consider the intrinsic bond between theatre and music, In the course of the 19th century, conceptions changed as to the though opera and ballet are what immediately come to mind, there nature and function of music. As a result, music lost its image as a 1. Prélude is yet another art form that embodies this association, and which subservient art, ultimately coming to be regarded as autonomous, 2. Minuetto especially in the 19th century enjoyed great popularity: incidental elevated, sublime and – in the terminology of writer, composer and 3. Adagietto music. In a period in which all theatres had either a pianist or a music critic E.T.A. Hoffmann – the most ‘romantic’ of all the arts. 4. Carillon smaller or larger orchestra in their employ, stage plays were generally His contemporary, the influential novelist and poet Ludwig Tieck, accompanied by music – much like in today’s films. And just as a was highly critical in respect of the function of incidental music. In Suite No. 2 substantial part of the drama in opera unfolds in the orchestra pit, his view, music should be used to conclude a stage play and, in so Arranged by Ernest Guiraud the music employed in the theatre likewise provided an additional doing, to retell the drama and its outcome without words. Tieck used layer of meaning, rather than mere depictions of mood. -

Fauré - 4 Duos Et Trios Avec Piano

FAURÉ - 4 DUOS ET TRIOS AVEC PIANO 1 The vocation of the Palazzetto Bru Zane – Centre de musique romantique française is to favour the rediscovery of the French musical heritage of the years 1780-1920, and to obtain for that repertoire the international recognition it deserves, and which is still lacking. Housed in Venice in a palazzo dating from 1695, specially restored for the purpose, the Palazzetto Bru Zane – Centre de musique romantique française is one of the achievements of the Fondation Bru. Combining artistic ambition with high scientific standards, the Centre reflects the humanist spirit that guides the actions of that foun- dation. The Palazzetto Bru Zane’s main activities, carried out in close collaboration with numerous partners, are research, the publication of books and scores, the organisa- tion and international distribution of concerts, support for teaching projects and the production of CD recordings. Le Palazzetto Bru Zane – Centre de musique romantique française a pour vocation de favoriser la redécouverte du patrimoine musical français du grand XIXe siècle (1780- 1920) en lui assurant le rayonnement qu’il mérite et qui lui fait encore défaut. Installé à Venise, dans un palais de 1695 restauré spécifiquement pour l’abriter, ce centre est une réalisation de la Fondation Bru. Il allie ambition artistique et exigence scienti- fique, reflétant l’esprit humaniste qui guide les actions de la fondation. Les principales activités du Palazzetto Bru Zane, menées en collaboration étroite avec de nombreux partenaires, sont la recherche, l’édition de partitions et de livres, la programmation et la diffusion de concerts à l’international, le soutien à des projets pédagogiques et la publication d’enregistrements discographiques. -

The MAY 2021 Newsletter!

Photo: Mark Holston Welcome to the MAY 2021 Newsletter! Our final newsletter of this school year! In this issue WAM!!!! – Richard Wagner’s Siegfried Idyll We hope that you have enjoyed these newsletters for the past several Introducing Our Soloist – Alicia McLean-Brischli months and that they have piqued your curiosity about classical Why do we call this Etude (ay-tude)? music. And don’t forget our Spring Festival started airing May 14th. Let’s Meet the Composers Gabriel Faure’, Richard Well, an etude in music is literally a This year there are two separate concerts, one featuring choral music Wagner “study” of some musical technique that and the other orchestral music. The concerts will be recorded and Musician Spotlight – Dr. Micah Hunter, Marshall requires practice. We hope this will be presented in a digital format. And as special nod to our students and Jones a fun way for you to “practice” learning teachers, as part of our WAM program we are offering you – Lots of dance-related about your symphony, chorale and Coming to Musical Terms COMPLIMENTARY TICKETS. Access to each concert will be available things this month other “noteworthy” things! for one week, so you have ample time to enjoy it in the classroom! All you have to do is call 406-407-7000 or email our box office manager Fun and Games – Faure’ and Wagner WordSearch at [email protected] and mention the word “etude” to get Summer at the Symphony – Rebecca Farm and your complimentary tickets. We hope to “see” you all there! So let’s Festival Amadeus wrap up this year and look forward to sharing with you again in the Ask the Maestro – John Zoltek Fall of 2021! Your Symphonic Toolbox – Soundscape Experience & “Little Concerts” WAM!!!!! (Wild About Music) Click below for this month’s empowering music learning experience!! Richard Wagner’s birthday is May 22nd, we invite you to hear a beautiful performance of his Siegfried Idyll, performed by select musicians from the Glacier Symphony. -

California State University, Northridge Recital And

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE RECITAL AND CONCERTO WORKS BY BACH, BEETHOVEN, RACHMANINOFF, DEBUSSY, ZHAO, and SHOSTAKOVICH A graduate project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Music in Music, Performance By Aiting Zheng May 2016 The graduate project of Aiting Zheng is approved: _____________________________________________ ____________________ Pro. Edward A Francis Date _____________________________________________ ____________________ Dr. Alexandra Monchick Date _____________________________________________ ____________________ Dr. Dmitry Rachmanov. Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii Table of Contents Signature Page…………...…………………………………….…………………..…......……ii Abstract…………...…………………………………………….……………….....……...…..iv French Suite No.5 in G Major, BWV 816, by Johann Sebastian Bach….……………..…..….1 Piano sonata No.27 in E minor, Op.90, by Ludwig van Beethoven…………..…..….........…..5 Etudes-Tableaux Op.39 No.4 in B minor and Op.33 No.4 in D minor, by Sergei Rachmaninoff………………………….…..…...………....8 Suite Bergamasque, by Claude Debussy………………….…………...……..….………........ 11 Pi Huang, by Zhao Zhang………………………………………………………....….….....…15 Concerto for piano, trumpet and string in C minor, Op.35 No.1, by Dmitri Shostakovich.…..17 Bibliography …………...……………………………………………………….…….…..…...20 Appendix A: Program I (Solo Recital).………………………….…………………….........…22 Appendix B: Program II (Concerto Recital)……………………...………………….…..…….24 iii ABSTRACT RECITAL AND CONCERTO By Aiting Zheng Master of Music in Music, Performance In the following paper, I will analyze works that I performed within a solo recital and a concerto recital. The recital consisted of works by Johann Sebastian Bach, Ludwig van Beethoven, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Claude Debussy, and Zhao Zhang, and the goal of the following analysis will be to research and explain the related performance practices of these composers. To a musician, interpretation is always of the utmost importance in the learning of a new work. -

Thursday Playlist

August 22, 2019: (Full-page version) Close Window “Lesser artists borrow, great artists steal.” — Igor Stravinsky Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, 00:01 Buy Now! Debussy Dialogue of the Wind and the Sea ~ La Mer Montreal Symphony/Dutoit Decca 478 3691 028947836919 Awake! 00:10 Buy Now! Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 1 in F minor, Op. 2 No. 1 Alfred Brendel Philips 442 124 028944212426 00:28 Buy Now! Kabalevsky Cello Concerto No. 2, Op. 77 Wallfisch/London Philharmonic/Thomson Chandos 8579 5014682857925 01:00 Buy Now! Gade Symphony No. 6 in G minor, Op. 32 Stockholm Sinfonietta/Jarvi BIS 355 7318590003565 01:25 Buy Now! Boccherini Guitar Quintet No. 7 in E minor Romero/Academy Chamber Ensemble Philips 438 769 028943876926 01:44 Buy Now! Wagner Overture ~ Tannhauser Cincinnati Symphony/Lopez-Cobos Telarc 80379 089408037924 Symphony No. 2 in C minor, Op. 17 "Little 02:00 Buy Now! Tchaikovsky Russian National Orchestra/Pletnev DG 477 8699 028947786993 Russian" 02:34 Buy Now! Handel Trio Sonata in B flat, Op. 2 No. 3 Heinz Holliger Wind Ensemble Denon 7026 N/A 02:45 Buy Now! Debussy Images for Piano, Series II Stephen Hough Hyperion 68139 034571281391 03:00 Buy Now! Beethoven Leonore Overture No. 2 Philharmonia Orchestra/Klemperer EMI 47190 N/A 03:15 Buy Now! Strauss Jr. Epigram Waltz, Op. 1 Vienna Philharmonic/Maazel RCA 61687 743216168729 Salerno-Sonnenberg/Soloists from the 1997 03:25 Buy Now! Brahms Sextet No. 1 in B flat, Op. 18 EMI Classics 56481 724355648129 Aspen Festival 04:03 Buy Now! Fauré Suite ~ Masques et Bergamasques, Op. -

SPCO 2019-20 Season Schedule

SPCO 2019-20 Season Schedule Opening Weekend: Jeremy Denk Plays Schumann’s Piano Concerto Friday, September 13, 8:00pm Saturday, September 14, 8:00pm Sunday, September 15, 2:00pm Ordway Concert Hall, Saint Paul Rossini: Overture to La scala di seta (The Silken Ladder) Schubert: Symphony No. 2 Schumann: Piano Concerto Led by SPCO musicians Jeremy Denk, director and piano Mozart’s Paris Symphony Thursday, September 19, 7:30pm Trinity Lutheran Church, Stillwater Friday, September 20, 8:00pm Wayzata Community Church, Wayzata Saturday, September 21, 8:00pm Saint Paul’s United Church of Christ, Saint Paul Tuesday, September 24, 7:30pm Shepherd of the Valley Lutheran Church, Apple Valley Friday, September 27, 11:00am Saturday, September 28, 8:00pm Ordway Concert Hall, Saint Paul Sunday, September 29, 2:00pm Ted Mann Concert Hall, Minneapolis Fauré: Suite from Masques et bergamasques Haydn: Symphony No. 87 Saint-Saëns: Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso for Violin and Orchestra Mozart: Symphony No. 31, Paris Led by SPCO musicians Eunice Kim, violin Beethoven’s First Symphony with Tabea Zimmermann Friday, October 11, 11:00am Friday, October 11, 8:00pm Wooddale Church, Eden Prairie Saturday, October 12, 8:00pm Ordway Concert Hall, Saint Paul Veress: Four Transylvanian Dances Schumann: Cello Concerto (arr. for viola by Tabea Zimmermann) Beethoven: Symphony No. 1 Tabea Zimmermann, director and viola Richard Egarr Plays Bach Friday, October 18, 11:00am Friday, October 18, 8:00pm Ordway Concert Hall, Saint Paul Saturday, October 19, 8:00pm Saint Paul’s United Church of Christ, Saint Paul Sunday, October 20, 3:00pm Saint Andrew’s Lutheran Church, Mahtomedi Bach: Orchestral Suite No. -

January 19, 2018

January 19, 2018: (Full-page version) Close Window “You become responsible, forever, for what you have tamed.” — Antoine de Saint-Exupery Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, 00:01 Buy Now! Liszt Ballade No. 2 in B minor Leif Ove Andsnes EMI 57002 72435700223 Awake! Rimsky- 00:17 Buy Now! Scheherazade, Op. 35 Druian/Minneapolis Symphony/Dorati Mercury 462 953 028946295328 Korsakov Orchestral Suite No. 4 in G, Op. 61 00:59 Buy Now! Tchaikovsky USSR Symphony/Svetlanov Melodiya 278825/26 3149023388256 "Mozartiana" 01:28 Buy Now! Vivaldi Flute Concerto in D, RV 428 "Il cardellino" Gazzelloni/I Musici Philips 426 949 028942694927 01:40 Buy Now! Schubert String Trio in B flat, D. 581 Grumiaux Trio Philips 438 700 028943870023 02:02 Buy Now! Sibelius Karelia Suite, Op. 11 Finnish Radio Symphony/Saraste RCA 7765 07863577652 02:17 Buy Now! Beethoven Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67 Vienna Philharmonic/Rattle EMI 57445 724355744524 02:50 Buy Now! Mozart Violin Sonata in C, K. 303 Stern/Bronfman Sony 64309 074646430927 03:02 Buy Now! Handel Concerto Grosso in E minor, Op. 6 No. 3 Academy of Ancient Music/Manze Harmonia Mundi 907228/29 093046722821 03:15 Buy Now! Field Piano Sonata in A, Op. 1 No. 2 O'Rourke Chandos 8787 095115878729 03:30 Buy Now! Diamond Symphony No. 3 Seattle Symphony/Schwarz Delos 3103 n/a 04:02 Buy Now! Chausson Symphony in B flat, Op. 20 BBC Philharmonic/Tortelier Chandos 9650 095115965023 04:37 Buy Now! Grieg Two Norwegian Dances, Op. -

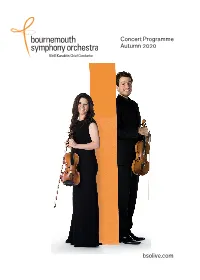

Bsolive.Com Concert Programme Autumn 2020

Concert Programme Autumn 2020 bsolive.com Welcome Welcome once again to the BSO’s autumn It will be interesting to hear how the concert series. I hope you’ve enjoyed the well-known scenes from fairy tales have concerts so far, and are looking forward to been augmented to make the larger, more delving into the plethora of fascinating substantial work. programmes coming up. The Library has been hard at work since July to bring this Saint-Saëns’s Second Symphony will have season’s music together for everyone to the finest examples of the weight of enjoy. Be rest assured, the sheet music has forty-five musicians working together to at least three days without contact before create music. The audience members going in front of the musicians at the first listening in the hall will feel the effect of rehearsal, and the same before it gets sheer air moving, and hopefully this will still sorted after the concert. be felt at home, through the power of myriad microphones, cables and digital “magic”, This week’s offering is entirely French, with until such times when we can all gather glorious melodies, vignettes of beloved again to feel that power together.. stories, and surging orchestral power. It’s a pleasure to work with Thierry Fischer again The BSO still needs all the support that can and welcome him back to Poole. be given so that we may all meet again, so thank you for ‘attending’ this concert, and I Fauré’s Masques et Bergamasques, a hope you enjoy the rest of the season.