Informatlon to USERS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fight Against International Terrorism: Cambodian Perspective

CICP Working Paper No.23. i No. 23 TThhee Fiigghhtt aggaaiinnsstt Inntteerrnnaattiioonnaall TTeerrrroorriissmm:: A Caammbbooddiiaann PPeerrssppeeccttiivvee Chheang Vannarith And Chap Sotharith April 2008 With Compliments This Working Paper series presents papers in a preliminary form and serves to stimulate comment and discussion. The views expressed are entirely the author’s own and not that of the Cambodian Institute for Cooperation and Peace Published with the funding support from The International Foundation for Arts and Culture, IFAC CICP Working Paper No.23. ii About Cambodian Institute for Cooperation and Peace (CICP) The CICP is an independent, neutral, and non-partisan research institute based in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. The Institute promotes both domestic and regional dialogue between government officials, national and international organizations, scholars, and the private sector on issues of peace, democracy, civil society, security, foreign policy, conflict resolution, economics and national development. In this regard, the institute endeavors to: organize forums, lectures, local, regional and international workshops and conference on various development and international issues; design and conduct trainings to civil servants and general public to build capacity in various topics especially in economic development and international cooperation; participate and share ideas in domestic, regional and international forums, workshops and conferences; promote peace and cooperation among Cambodians, as well as between Cambodians and others through regional and international dialogues; and conduct surveys and researches on various topics including socio-economic development, security, strategic studies, international relation, defense management as well as disseminate the resulting research findings. Networking The Institute convenes workshops, seminars and colloquia on aspects of socio-economic development, international relations and security. -

Flt I Lrt HE Dr. Haruhisa Handa Advisor to the Prime

Chairman, Asian Economic Forum H.E. Dr. Haruhisa Handa Advisor to the Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Cambodia; Advisor to the Royal Government of Cambodia; Founder and Chairman, Asia Economic Forum; Chancellor, The University of Cambodia; President and Founder, International Foundation for Arts and Culture H.E. Dr. Haruhisa Handa is a highly-praised business man, a respected philanthropist, a successful author, a musician, poet, painter, dancer, and a motivational speaker. He received his B.A. in Economics at Doshisha University and later received an M.A. in Vocal Music from Musashino Academia Musicae. H.E. Dr. Handa went on to acquire an M.A. in Creative Arts from Edith Cowan University in Australia, which also later awarded him an honorary doctorate. He is also an ordained Zen Buddhist priest in the Rinzai tradition. H.E. Dr. Handa has served as a guest lecturer at numerous esteemed universities around the world, sharing his extensive experience and knowledge. Currently, he operates several overseas companies; and serves as Vice-Chairman of the International Shinto Foundation, the President and Founder of the International Foundation for Arts and Culture, the Vice-Chairman of the Sihanouk Hospital, an Advisor to the Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Cambodia, the Chancellor of the University of Cambodia, and the Founder and Chairman of the Asia Economic Forum (AEF). Vice-Chairman, Asian Economic Forum H.E. Dr. Kao Kim Hourn Advisor to the Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Cambodia; Member, Supreme National Economic Council; Secretary of State, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation; Vice-Chairman of AEF; President, The University of Cambodia H.E. -

Road to a Settlement in Cambodia

120 Nadezhda Bektimirova OAD TO A SETTLEMENT RIN CAMBODIA A new state – the People’s Republic of Kampuchea (PRK) appeared on the political map of the world in January 1979. Under the onslaught of the 150-thousand-strong Vietnamese forces the Khmer Rouge tyranny crumbled. The Cambodian people acquired an opportunity to return to a normal life. However, most countries which verbally condemned the Pol Pot genocide did not recognize the PRK. The Nadezhda Soviet Union and other socialist countries were the only BEKTIMIROVA exception. The concept of “humanitarian intervention” has not yet been invented. Vietnam was denounced for D.Sc.(Hist.), the “occupation” of Cambodia. There were demands to the head of the withdraw the Vietnamese troops immediately. Department A conflict that flared up around Cambodia was a of the History of Far product of the confrontation between the U.S.S.R. and Eastern and Southeast the U.S.A. and between the U.S.S.R. and the PRC, a typical Asian countries Cold War era phenomenon. The proclamation of the of the Institute PRK and the events preceding it were interpreted in of Asian Washington and Beijing as a drastic violation of the and African Countries regional balance of forces and a crude manifestation of at Lomonosov “Soviet hegemonism.”1 Moscow State The international isolation of the PRK only enhan- University ced its orientation to the Soviet Union, Vietnam and their partners and increased its political and econo- mic dependence on them. The annual volume of aid International Affairs Road to a Settlement in Cambodia -

H.E. Dr. Kao Kim Hourn

Welcome Remarks By H.E. Dr. Kao Kim Hourn Founder and President of the University of Cambodia and Minister Delegate attached to the Prime Minister December 30th, 2014 Respected Excellences, honored guests, graduating students, distinguished faculty and staff, family members and friends: It is my great pleasure to welcome you all to the University of Cambodia’s 10th annual Graduation Ceremony. Today we gather together to honor not only our graduates, but also those who have supported them and encouraged them; financially, emotionally, and spiritually throughout the turbulent journey that is the university experience. Families, friends, and faculty, as we celebrate the accomplishments of your loved ones; remember - this is your day too. Please give them a round of applause. Today we are pleased to have many honored guests in attendance; I would like to take a brief moment to thank them for their time, and to welcome them to UC. H.E. Hang Chuon Naron, Minister of Education, Youth and Sport, H.E. Oknha Chear Ratana, Professor David Cohen, and Mr. Wang Jiemin. Please give them a warm welcome. Since its founding, The University of Cambodia has become one of the leading and most reputable higher education institutions in Cambodia. The University has fostered an intellectual community where the faculty facilitates a deeper understanding of the subject matter, and students are encouraged to develop critical thinking skills, create and share knowledge, refine and challenge ideas, and serve their families and communities through social work. The rigorous and supportive learning environment at UC fosters open and constructive dialogue and promotes strong critical, analytical, and creative thinking skills among students. -

The Commencement of the 14Th Annual Graduation Ceremony 2018

THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBODIA THE COMMENCEMENT OF THE 14TH ANNUAL GRADUATION CEREMONY 2018 ON DECEMBER 21st, 2018 THREE O’CLOCK IN THE AFTERNOON AT THE SEATV AUDITORIUM PHNOM PENH, KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA 0 THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBODIA THE COMMENCEMENT OF THE 14th ANNUAL GRADUATION CEREMONY 2018 DECEMBER 21st, 2018 THREE O’CLOCK IN THE AFTERNOON AT THE SEATV AUDITORIUM PHNOM PENH, KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA 1:30 PM Arrival of Students, Faculty Members and Parents 2:30 PM Arrival of National and International Guests 3:00 PM Arrival of H.E. Dr. KAO Kim Hourn, Fouder, Chairman of Board of Trustees and President of The University of Cambodia OPENING SESSION The National Anthem Report on the Annual Graduation by Dr. Suy Sareth, Dean for The School of Undergraduate Studies, The University of Cambodia Keynote Address by Dr. Kao Kim Hourn, Founder, Chairman of the Board of Trustees, and President of The University of Cambodia Video Clip on the History of UC’s Graduations CONFERRING OF THE CERTIFICATES OF RECOGNITION TO OUTSTANDING STAFF, FACULTY, AND STUDENTS, AS WELL AS ACADEMIC DEGREES 1. CONFERRING OF THE CERTIFICATES OF RECOGNITION TO OUTSTANDING STAFF: LCT. Khem Rany, Member of the Board of Trustees and Vice President for General Affairs of The University of Cambodia and Director-General of Southeast Asia Television (SEATV) 2. CONFERRING OF THE CERTIFICATES OF RECOGNITION TO OUTSTANDING FACULTY: LCT. Khem Rany, Member of the Board of Trustees and Vice President for General Affairs of The University of Cambodia and Director-General of Southeast Asia Television (SEATV) 1 3. CONFERRING OF MEDALS OF HONOR FOR THE TOP FIVE OUTSTANDING BACHELOR’S DEGREE GRADUATES: H.E. -

CICP Working Paper No. 14: Cambodia's Engagement with ASEAN

CICP Working Paper No.14. i No. 14 Cambodia’s Engagement with ASEAN: Lessons for Timor Leste Din Merican February 2007 With Compliments This Working Paper series presents papers in a preliminary form and serves to stimulate comment and discussion. The views expressed are entirely the author’s own and not that of the Cambodian Institute for Cooperation and Peace Published with the funding support from The International Foundation for Arts and Culture, IFAC CICP Working Paper No.14. ii About Cambodian Institute for Cooperation and Peace (CICP) The CICP is an independent, neutral, and non-partisan research institute based in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. The Institute promotes both domestic and regional dialogue between government officials, national and international organizations, scholars, and the private sector on issues of peace, democracy, civil society, security, foreign policy, conflict resolution, economics and national development. In this regard, the institute endeavors to: organize forums, lectures, local, regional and international workshops and conference on various development and international issues; design and conduct trainings to civil servants and general public to build capacity in various topics especially in economic development and international cooperation; participate and share ideas in domestic, regional and international forums, workshops and conferences; promote peace and cooperation among Cambodians, as well as between Cambodians and others through regional and international dialogues; and conduct surveys and researches on various topics including socio-economic development, security, strategic studies, international relation, defense management as well as disseminate the resulting research findings. Networking The Institute convenes workshops, seminars and colloquia on aspects of socio-economic development, international relations and security. -

The Indochinese Enlargement of ASEAN: Security Expectations and Outcomes

Australian Journal of International Affairs Vol. 59, No. 1, pp. 71–88, March 2005 The Indochinese enlargement of ASEAN: security expectations and outcomes Ralf Emmers The article examines the extent to which Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia have gained from their participation in ASEAN. To assess the security and diplomatic benefits of their membership, it identifies three expectations held by the Indochinese states—enhanced international status, improved security and relations vis-a`-vis other ASEAN members, and more room for manoeuvre when dealing with non-member states. The study demonstrates, however, that while Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia are less isolated internationally after joining ASEAN, the actual benefits in terms of their relations with the other ASEAN members as well as non-member states have been more ambiguous. With ASEAN in mind, the article concludes by discussing the possible costs and drawbacks of enlargement that can transform any international organisation into a less influential and cohesive institution. Introduction Since its establishment in August 1967, the original members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) had hoped to unite the entire Southeast Asian region under its auspices1. The end of the Cold War made this possible. While the Association had first been enlarged to include Brunei in January 1984, its post-Cold War expansion started with Vietnam in July 1995. Laos and Myanmar joined ASEAN in July 1997 while Cambodia gained its full membership in April 1999. The absence of specific political and economic conditions for admission enabled the candidates to rapidly enter the regional grouping. The Association that they joined in the second half of the 1990s was in some respects not comparable to the one that had been transformed by the Cambodian conflict (1978–1991) into an institution well-respected by the international community. -

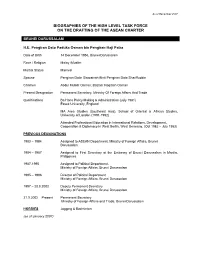

Brief Biographies of the High Level Task Force (HLTF)

As of December 2007 BIOGRAPHIES OF THE HIGH LEVEL TASK FORCE ON THE DRAFTING OF THE ASEAN CHARTER BRUNEI DARUSSALAM H.E. Pengiran Dato Paduka Osman bin Pengiran Haji Patra Date of Birth 14 December 1956, Brunei Darussalam Race / Religion Malay /Muslim Martial Status Married Spouse Pengiran Datin Shazainah Binti Pengiran Dato Shariffuddin Children Abdul Mubdi’ Osman; Bazlaa’ Naqibah Osman Present Designation Permanent Secretary, Ministry Of Foreign Affairs And Trade Qualifications Ba Hons Policy Making & Administration (July 1981) Essex University, England MA Area Studies (Southeast Asia), School of Oriental & African Studies, University of London (1991-1992) Attended Professional Education in International Relations, Development, Cooperation & Diplomacy in West Berlin, West Germany, (Oct 1982 – July 1983) PREVIOUS DESIGNATIONS 1983 – 1984 Assigned to ASEAN Department, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Brunei Darussalam 1984 – 1987 Assigned to First Secretary at the Embassy of Brunei Darussalam in Manila, Philippines 1987-1995 Assigned to Political Department, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Brunei Darussalam 1995 – 1996 Director of Political Department Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Brunei Darussalam 1997 – 20.8.2002 Deputy Permanent Secretary Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Brunei Darussalam 21.9.2002 – Present Permanent Secretary Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Brunei Darussalam HOBBIES Jogging & Badminton (as of January 2007) As of December 2007 CAMBODIA H.E. Dr KAO Kim Hourn Dr. Kao was born in Cambodia and educated in the United States of America. Over the years, he attended many national, regional and international meetings (bilateral and multilateral; official and track-two). As a scholar and diplomat, he had made various contributions to both Cambodia and ASEAN. EDUCATION • B.A., Asian Studies, Baylor University, U.S.A., 1989. -

Published by the Cabinet of Samdech Hun Sen MP of Kandal Prime

Published by the Cabinet of Samdech Hun Sen —————— MP of Kandal Prime Minister Issue 78 http://www.cnv.org.kh July, 2004 25 July 2004 (Unofficial Translation) 30 July 2004 (Unofficial Translation) Inspecting the Construction of a Bailey Bridge in Reconstructing the National Road 3 between Koh Sotin District of Kompong Cham Province Kompot Town and Tropeang Ropov Following is the selected com- Republic of Korea (RoK), who ments, aside from the pre- financed the project, I am pared text, of Samdech Hun pleased and thankful to the Sen at the groundbreaking people and Government of the ceremony to rebuild the na- RoK for the assistance and tional road three between support they have always pro- Kompot Town and Tropeang vided for the Cambodian peo- Ropov, the last 32.7 kilome- ple and Government. ters length that is connected to another part that is con- … The construction site here is structed by the World Bank one of the three projects that I from Veal Rinh to Tropeang have negotiated with RoK – Ropov. (1) information technology project and (2) the construction “… I am sure that today’s of a large professional training event is what we all have been centre, which is supposed to be 25 July 04 - Samdech Hun Sen (centre) accompanies an old-age waiting for. With the presence ready by end of the year, (3) person in his wheelchair to cross the Tonle Touch River by the of HE Ambassador of the (Continued on page 3) newly built Doeum Sdao Bailey Bridge at Koh Sotin district, Kom- 20 July 2004 (Unofficial Translation) pong Cham province (Photo: Virakmuny). -

Cambodia Within ASEAN: Twenty-Years in the Making

Cambodia Within ASEAN: Twenty-Years in the Making Pich Charadine Edited by Robert Hör Cambodia within ASEAN: Twenty-Years in the Making Pich Charadine March | 2020 ABOUT KONRAD-ADENAUER-STIFTUNG Freedom, justice and solidarity are the basic principles underlying the work of the Konrad-Adenauer- Stiftung (KAS). The KAS is a political foundation, closely associated with the Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU). As co-founder of the CDU and the first Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany, Konrad Adenauer (1876-1967) united Christian-social, conservative and liberal traditions. His name is synonymous with the democratic reconstruction of Germany, the firm alignment of foreign policy with the trans-Atlantic community of values, the vision of a unified Europe and an orientation towards the social market economy. His intellectual heritage continues to serve both as our aim as well as our obligation today.In our European and international cooperation efforts we work for people to be able to live self-determined lives in freedom and dignity. We make a contribution underpinned by values to helping Germany meet its growing responsibilities throughout the world. KAS has been working in Cambodia since 1994, striving to support the Cambodian people in fostering dialogue, building networks and enhancing scientific projects. Thereby, the foundation works towards creating an environment conducive to economic and social development. All programs are conceived and implemented in close cooperation with the Cambodian partners on central and sub-national levels. ABOUT CAMBODIAN INSTITUTE FOR COOPERATION AND PEACE The Cambodian Institute for Cooperation and Peace (CICP), founded in 1994, is a neutral, non-govern- mental, non-profit and non-partisan foreign policy think-tank institution based in Phnom Penh. -

List of Confirmed Speakers of the 2Nd AEF

List of Confirmed Speakers of the 2nd AEF Samdech Hun Sen, Prime Minister, Royal Government of Cambodia H.E. Keat Chhon, Senior Minister, Minster of Economy and Finance, Cambodia H.E. Katherine Marshall, Vice President, The World Bank, Washington, D.C. H.E. Ong Keng Yong, Secretary-General of ASEAN, Jakarta Dr. Haruhisa Handa, Founding Chairman, Asia Economic Forum; Chancellor, University of Cambodia; President and Founder, International Foundation for Arts and Culture H.E. Dr. Aun Porn Moniroth, Chairman, Supreme National Economic Council (SNEC); Secretary of State, Ministry of Economy and Finance; and Economic Advisor to the Prime Minister H.E. Jose T. Almonte, Former National Security Adviser, Philippines H.E. Dr. Narongchai Akrasanee, Chairman, Serenee Holdings Co., Ltd., Director of the Mekong Institute, and Vice Chairman of the Executive Board of Industrial Finance Corporation of Thailand Oknha Kith Meng, Chairman, Phnom Penh Chamber of Commerce Tan Sri Dato’ Mohd Ramli Kushairi, Special Envoy of Malaysian Prime Minister, Malaysia Ambassador Kawato Akio, Chief Economist at the Development Bank of Japan and Member of the Council on East Asian Community The Hon. David Malcolm, Chief Justice, the Supreme Court of Western Australia, Australia Professor Simon Tay, Chairman, Singapore Institute of International Affairs, Singapore Dr. Greg Emery, Executive Director, International Outreach and Development (Office of the President); Director, Global Leadership Center, Ohio University Dr. Kao Kim Hourn, Secretary-General, Asia Economic Forum; President, University of Cambodia; Secretary of State, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, Cambodia H.E. Dr. Hang Chuon Naron, Secretary-General, Ministry of Economy and Finance; Secretary-General, Supreme National Economic Council, Cambodia Dr. -

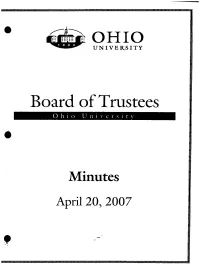

Board of Trustees Oh Io Universit Y

• ell Ole OHIO U NI VE R_S ITY Board of Trustees Oh io Universit y Minutes April 20, 2007 • MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF • THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF OHIO UNIVERSITY Friday, April 20, 2007 Margaret M. Walter Hall, Governance Room Ohio University, Athens Campus • THE OHIO UNIVERSITY BOARD OF TRUSTEES MINUTES OF April 20, 2007 MEETING TABLE OF CONTENTS Minutes of February 16, 2007 Executive Committee (Tab 1) • Executive Session of the Executive Committee Minutes of April 19-20, 2007 555 • Honorary Degree Awards, Resolution 2007 — 2088 557 • Meeting Dates for Succeeding Years 562 Academic Quality Committee (Tab 2) • Academic Quality Committee Minutes 563 • School Status for the a y. Voinovich Center of Leadership and Development, Resolution 2007 — 2089 569 • Faculty Emeritus/Emerita Awards, Resolution 2007 — 2090 572 • Faculty Fellowship Awards, Resolution 2007 — 2091 577 • Naming of the Proctorville Center Building, Resolution 2007 — 2092 588 • Academic Program Reviews: Department of Civil Engineering, Department of Industrial and Manufacturing Systems Engineering, Department of Mechanical Engineering, School of Physical Therapy, Resolution 2007 — 2093 590 • Appointment of Regional Coordinating Councils, Resolution 2007 — 2094 683 Audit, Finance, Facilities, and Investment Committee (Tab 3) • Audit, Finance, Facilities, and Investment Committee Minutes 707 • Approval of Projects and Authorization to Hire Consultants, Develop Construction Documents, Receive Bids and Award Contracts for Basic Renovation Projects on the Athens and Regional Campuses, Resolution 2007 — 2095 712 • Approval of Construction Documents and Authority to Receive Bids and Award Construction Contracts for the Porter Hall Addition, Resolution 2007 — 2096 721 Student Life, Human Resources, and Athletics (Tab 4) • Student Life, Human Resources, and Athletics Committee Minutes 771 • Ratification of AFSCME Labor Agreement, Resolution 2007 — 2097 776 Reports (Tab 5) • Provosts Report 826 • Presidents Report 842 ROLL CALL Eight Trustees were present – Chairman R.