Iga—The Tree That Walked

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flinders Ranges National Park 640 641 642 Bunkers643 Page 83 CR 1:400 000 Page 84 Page 85 Page 86 FR 7 Regional Map

INDEX TO 1:100 000 MAPS 940 FR 9 Page 105 Page 21 Arkaroola Village 880 881 Page 103 Page 104 Vulkathunha - Gammon Ranges National Park Copley Leigh Balcanoona 817 Creek 818 819 820 Nepabunna 821 Page 97 Page 98 Page 99 822 Page 100 Page 101 Page 102 Ediacara CP Beltana 758 759 760 761 762 0 10 20 30 Page 91 Page 92 763 Page 93 Page 94 Page 95 Page 96 kilometres FR 7 FR 8 Page 19 Page 20 Lake Torrens Blinman National Park 699 Parachilna CFS REGIONAL 700 701 702 Page 87 Page 88 Page 89 Page 90 BOUNDARIES Lake Torrens Flinders Ranges National Park 640 641 642 Bunkers643 Page 83 CR 1:400 000 Page 84 Page 85 Page 86 FR 7 Regional map Wilpena Pound 581 582 583 Page 79 584 1:100 000 Page 80 Page 81 Page 82 940 Topographic map REGION 4 Hawker See 1:50 000 522 523 524 enlargements from Page 75 525 page 106 Page 76 Page 77 Page 78 FR 4 FR 5 Page 15 Page 16 Cradock FR 6 See town enlargements Page 17 from page 160 473 474 475 476 477 478 479 Page 69 Page 70 Page 71 480 Page 67 Page 68 Page 72 Page 73 Page 74 The Dutchmans Stern CP DEWNR reserve Quorn Mount Carrieton Brown CP MAP BOOK PAGE ORDER 432 433 434 435 436 437 438 439 440 Page 57 Page 58 Page 60 Page 61 441 442 Page 55 Page 56 Page 59 Page 62 Page 63 Page 64 Page 65 Port Augusta Stirling North 699 700 701 702 Lincoln Gap Yalpara CP Yunta Wilmington Winninowie Black Rock CP 640 641 642 643 Morchard Orroroo CP 394 395 396 397 398 399 400 401 Page 45 Page 46 Page 47 Page 48 402 403 404 Page 43 Page 44 Mount Page 49 Page 50 Page 51 Remarkable Page 52 Page 53 Black Rock Mambray Creek NP Melrose -

Appendix A: Consultation and Coordination

APPENDIX A: CONSULTATION AND COORDINATION Virgin Islands National Park July 2013 Caneel Bay Resort Lease This page intentionally left blank Virgin Islands National Park July 2013 Caneel Bay Resort Lease A-1 Virgin Islands National Park July 2013 Caneel Bay Resort Lease A-2 Virgin Islands National Park July 2013 Caneel Bay Resort Lease A-3 Virgin Islands National Park July 2013 Caneel Bay Resort Lease A-4 Virgin Islands National Park July 2013 Caneel Bay Resort Lease A-5 Virgin Islands National Park July 2013 Caneel Bay Resort Lease A-6 APPENDIX B: PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT Virgin Islands National Park July 2013 Caneel Bay Resort Lease This page intentionally left blank Virgin Islands National Park July 2013 Caneel Bay Resort Lease B-1 Virgin Islands National Park July 2013 Caneel Bay Resort Lease B-2 Virgin Islands National Park July 2013 Caneel Bay Resort Lease B-3 APPENDIX C: VEGETATION AND WILDLIFE ASSESSMENTS Virgin Islands National Park July 2013 Caneel Bay Resort Lease VEGETATION AND WILDLIFE ASSESSMENTS FOR THE CANEEL BAY RESORT LEASE ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT AT VIRGIN ISLANDS NATIONAL PARK ST. JOHN, U.S. VIRGIN ISLANDS Prepared for: National Park Service Southeast Regional Office Atlanta, Georgia March 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... ii LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................................ ii LIST OF ATTACHMENTS ...................................................................................................... -

![96 C.L.R.] of Australia. 563 Elder's Trustee And](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6383/96-c-l-r-of-australia-563-elders-trustee-and-66383.webp)

96 C.L.R.] of Australia. 563 Elder's Trustee And

96 C.L.R.] OF AUSTRALIA. 563 [HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA.] ELDER'S TRUSTEE AND EXECUTORY APPELLANT ; COMPANY LIMITED . ./ AND FEDERAL COMMISSIONER OF TAXATION RESPONDENT. Estate Duty {Cth.)—Company shares—Valuation—Principles to be applied—Com- H. C. OF A. pany engaged in pastoral pursuits in semi-arid areas—-Weight to be attached to 1951. results in past years—-Allowance for reserves—Estate Duty Assessment Act 1914-1942. Adelaide, Sept. 21, 24, The estate of a deceased person included a small proportion of the issued 25; shares of a company which owned and operated four grazing properties. One Sydney, property had been and one was about to be converted from sheep to cattle, Nov. 5. and the other two were sheep stations. All were in semi-arid areas and sub- ject to special hazards. The company's shares were not quoted on a stock Kitto J. exchange. Held that in applying ordinary principles of valuation to the valuation of shares, it should be recognised that ordinarily a purchaser is likely to be influenced, as to price, mainly by his opinion concerning the dividends which the shares may reasonably be expected to produce. In the present case, having regard to the nature and characteristics of the company's business, a hypothetical purchaser buying at the date of death of the deceased would have looked for a high assets-backmg for the shares, as well as for a high average dividend arrived at after making substantial allowances for reserves. The selection of suitable test periods, and the adjustments to be made in using the company's accounts of the selected periods in order to estimate the profits which might have been regarded at the date of death as likely to be made by the company in the future, considered. -

Arkaroola Geology Information Leaflet

Arkaroola: A prime Australian site for Mars analogue field research Mars-Oz at Arkaroola: A Prime Australian Site for Mars Analogue Field Research Jonathan D. A. Clarke ([email protected]) and David Willson ([email protected]) Mars Society Australia Mars Society Australia has selected the Arkaroola region in South Australia as its prime area for Mars analogue research. The region is accessible by road and air from Adelaide, the capital of South Australia. Much of the central part of the region is held under private leasehold as a wilderness sanctuary. The lessees are highly supportive of scientific and technological research. The region and its hinterland have a diversity of geological and astrobiological features of interest for Mars research and Mars exploration. These include: GEOLOGY • Modern and ancient (Neoproterozoic, Carboniferous) hydrothermal systems; • Gravel outwash plains of the present desert environment; • Late Proterozoic Wooltana Basalt with localised quartz-haematite breccia veins; • Neoproterozoic evaporitic non-clastic and minor carbonate sediments Of the Callanna and Burra Groups; • Pre-Cretaceous weathering surfaces; • Cretaceous marine shoreline deposits; • Playa lakes • Artesian springs; • Dune fields; • Iron, silica, carbonate and sulphate duricrusts; • Pleistocene high level gravels of fans and pediments, and • Holocene creek gravels. BIOLOGY AND PALAEONTOLOGY • Modern extremophile populations in uranium and sulphide mineralisation; • Extremophiles associated with radioactive hydrothermal springs; -

Total Solar Eclipse of 2002 December 4

NASA/TP—2001–209990 Total Solar Eclipse of 2002 December 04 F. Espenak and J. Anderson Central Lat,Lng = -28.0 132.0 P Factor = 0.46 Semi W,H = 0.35 0.28 Offset X,Y = 0.00-0.00 1999 Oct 26 10:40:42 AM High Res World Data [WPD1] WorldMap v2.00, F. Espenak Orthographic Projection Scale = 8.00 mm/° = 1:13915000 Central Lat,Lng = -10.0 26.0 P Factor = 0.31 Semi W,H = 0.70 0.50 Offset X,Y = 0.00-0.00 1999 Oct 26 10:17:57 AM September 2001 The NASA STI Program Office … in Profile Since its founding, NASA has been dedicated to • CONFERENCE PUBLICATION. Collected the advancement of aeronautics and space papers from scientific and technical science. The NASA Scientific and Technical conferences, symposia, seminars, or other Information (STI) Program Office plays a key meetings sponsored or cosponsored by NASA. part in helping NASA maintain this important role. • SPECIAL PUBLICATION. Scientific, techni- cal, or historical information from NASA The NASA STI Program Office is operated by programs, projects, and mission, often con- Langley Research Center, the lead center for cerned with subjects having substantial public NASA’s scientific and technical information. The interest. NASA STI Program Office provides access to the NASA STI Database, the largest collection of • TECHNICAL TRANSLATION. aeronautical and space science STI in the world. English-language translations of foreign scien- The Program Office is also NASA’s institutional tific and technical material pertinent to NASA’s mechanism for disseminating the results of its mission. -

Clamor Schürmann's Barngarla Grammar This Book Is Available As a Free Fully-Searchable Ebook from Clamor Schürmann's Barngarla Grammar

Clamor Schürmann's Barngarla grammar This book is available as a free fully-searchable ebook from www.adelaide.edu.au/press Clamor Schürmann's Barngarla grammar A commentary on the first section of A vocabulary of the Parnkalla language (revised edition 2018) by Mark Clendon Linguistics Department, Faculty of Arts The University of Adelaide Clamor Wilhelm Schürmann Published in Adelaide by University of Adelaide Press The University of Adelaide Level 14, 115 Grenfell Street South Australia 5005 [email protected] www.adelaide.edu.au/press The University of Adelaide Press publishes externally refereed scholarly books by staff of the University of Adelaide. It aims to maximise access to the University’s best research by publishing works through the internet as free downloads and for sale as high quality printed volumes. © 2015 Mark Clendon, 2018 for this revised edition This work is licenced under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. This licence allows for the copying, distribution, display and performance of this work for non-commercial purposes providing the work is clearly attributed to the copyright holders. Address all inquiries to the Director at the above address. For the full Cataloguing-in-Publication data please contact the National Library of Australia: [email protected] -

A Dictionary of Diyari, South Australia

A Dictionary of Diyari, South Australia Peter K. Austin A Dictionary of Diyari, South Australia © 2013 Peter K. Austin Department of Linguistics, SOAS, University of London Russell Square, London WC1H 0XG United Kingdom [email protected] Preface Diyari is an Australian Aboriginal language spoken by a few Dieri people living at various places in the north-east of South Australia and in Broken Hill, New South Wales. Although the language is no longer in regular use among Dieri families there is still a lot of knowledge about the language held by community members who are keen to see it preserved and passed on to younger generations. This book is a draft reference dictionary of Diyari based primarily on materials collected during my fieldwork on the language in 1974-77 and subsequent research. A companion grammar is also available, and a text collection is in preparation. This book will be revised and extended as further work on the language is undertaken, based on recordings made by myself and Luise Hercus in the 1970s, together with new materials provided by current speakers and Dieri community members. I dedicate this book to the Dieri karna. London and Canberra January 2013 Acknowledgements This study would not have been possible without the interest and help of the speakers of Diyari I worked with in the 1970s, together with members of the Dieri Aboriginal Corporation since 2010. I owe a particular debt of gratitude to the late Ben Murray, Rosa Warren and the Frieda Merrick who spent so much time teaching me Diyari and sharing with me their memories of “the old days”. -

Vol No Artist Title Date Medium Comments 1 Acraman, William

Tregenza PRG 1336 SOUTH AUSTRALIAN HISTORICAL PICTURES INDEX ARTIST INDEX (Series 1) (Information taken from photo - some spellings may be incorrect) Vol No Artist Title Date Medium Comments 1 Acraman, William Residence of E Castle Esq re Hackham Morphett Vale 1856 Pencil 1 Adamson, James Hazel Early South Australian view 1 Adamson, James Hazel Lady Augusta & Eureka Capt Cadell's first vessels on Murray 1853 Lithograph 1 Adamson, James Hazel The Goolwa 1853 Lithograph 1 Adamson, James Hazel Agricultural show at Frome Road 1853 W/c 1 Adamson, James Hazel Jetty at Port Noarlunga with Yatala in background 1855 W/c 1 Adamson, James Hazel Panorama of Goolwa from water showing Steamer Lady Augusta 1854 Pencil & wash No photo 1 Angas, George French SA Illustrated photocopies of plates List in front 1 Angas, George French Portraits (2) 1 Angas, George French Devil's Punch Bowl 1844 W/c 1 Angas, George French Encounter Bay looking south 1844 W/c 1 Angas, George French Interior of crater, Mount Shanck 1844 W/c Plus current 1 Angas, George French Lake Albert 1844 W/c 1 Angas, George French Mt Lofty from Rapid Bay W/c 1 Angas, George French Interior of Principal Crater Mt Gambier - evening 1844 W/c 1 Angas, George French Penguin Island near Rivoli Bay 1844 W/c 1 Angas, George French Port Adelaide 1844 W/c 1 Angas, George French Port Lincoln from Winter's Hill 1845 W/c 1 Angas, George French Scene of the Coorong at the Narrows 1844 W/c 1 Angas, George French The Goolwa - evening W/c 1 Angas, George French Sea mouth of the Murray 1844-45 W/c 1 Angas, -

Aboriginal Agency, Institutionalisation and Survival

2q' t '9à ABORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND PEGGY BROCK B. A. (Hons) Universit¡r of Adelaide Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History/Geography, University of Adelaide March f99f ll TAT}LE OF CONTENTS ii LIST OF TAE}LES AND MAPS iii SUMMARY iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . vii ABBREVIATIONS ix C}IAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION I CFIAPTER TWO. TI{E HISTORICAL CONTEXT IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA 32 CHAPTER THREE. POONINDIE: HOME AWAY FROM COUNTRY 46 POONINDIE: AN trSTä,TILISHED COMMUNITY AND ITS DESTRUCTION 83 KOONIBBA: REFUGE FOR TI{E PEOPLE OF THE VI/EST COAST r22 CFIAPTER SIX. KOONIBBA: INSTITUTIONAL UPHtrAVAL AND ADJUSTMENT t70 C}IAPTER SEVEN. DISPERSAL OF KOONIBBA PEOPLE AND THE END OF TI{E MISSION ERA T98 CTIAPTER EIGHT. SURVTVAL WITHOUT INSTITUTIONALISATION236 C}IAPTER NINtr. NEPABUNNA: THtr MISSION FACTOR 268 CFIAPTER TEN. AE}ORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND SURVTVAL 299 BIBLIOGRAPI{Y 320 ltt TABLES AND MAPS Table I L7 Table 2 128 Poonindie location map opposite 54 Poonindie land tenure map f 876 opposite 114 Poonindie land tenure map f 896 opposite r14 Koonibba location map opposite L27 Location of Adnyamathanha campsites in relation to pastoral station homesteads opposite 252 Map of North Flinders Ranges I93O opposite 269 lv SUMMARY The institutionalisation of Aborigines on missions and government stations has dominated Aboriginal-non-Aboriginal relations. Institutionalisation of Aborigines, under the guise of assimilation and protection policies, was only abandoned in.the lg7Os. It is therefore important to understand the implications of these policies for Aborigines and Australian society in general. I investigate the affect of institutionalisation on Aborigines, questioning the assumption tl.at they were passive victims forced onto missions and government stations and kept there as virtual prisoners. -

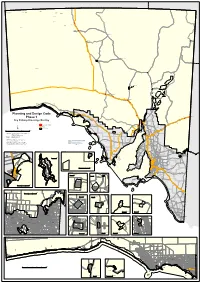

Key Railway Crossings Overlay 113411.4 94795 ! Port Augusta ! !

N O R T H E R N T E R R I T O R Y Amata ! Kalka Kanpi ! ! Nyapari Pipalyatjara ! ! Pukatja ! Yunyarinyi ! Umuwa ! QUEENSLAND Kaltjiti ! !113411.4 94795 Indulkana ! Mimili ! Watarru ! 113411.4 94795 Mintabie ! ! ! Marla Oodnadatta ! Innamincka Cadney Park ! ! Moomba ! WESTERN AUSTRALIA William Creek ! Coober Pedy ! Oak Valley ! Marree ! ! Lyndhurst Arkaroola ! Andamooka ! Roxby Downs ! Copley ! ! Nepabunna Leigh Creek ! Tarcoola ! Beltana ! 113411.4 94795 !! 113411.4 94795 Kingoonya ! Glendambo !113411.4 94795 Parachilna ! ! Blinman ! Woomera !!113411.4 94795 Pimba !113411.4 94795 Nullarbor Roadhouse Yalata ! ! ! Wilpena Border ! Village ! Nundroo Bookabie ! Coorabie ! Penong ! NEW SOUTH WALES ! Fowlers Bay FLINDERS RANGES !113411.4 94795 Planning and Design Code ! 113411.4 94795 ! Ceduna CEDUNA Cockburn Mingary !113411.4 94795 ! ! Phase 1 !113411.4 94795 Olary ! Key Railway Crossings Overlay 113411.4 94795 ! Port Augusta ! ! !113411.4 94795 Manna Hill ! STREAKY BAY Key Railway Crossings Yunta ! Iron Knob Railway MOUNT REMARKABLE ± Phase 1 extent PETERBOROUGH 0 50 100 150 km Iron Baron ! !!115768.8 17888 WUDINNA WHYALLA KIMBA Whyalla Produced by Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure Development Division ! GPO Box 1815 Adelaide SA 5001 Port Pirie www.sa.gov.au NORTHERN Projection Lambert Conformal Conic AREAS Compiled 11 January 2019 © Government of South Australia 2019 FRANKLIN No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted PORT in any form, or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, HARBOUR Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure. PIRIE ELLISTON CLEVE While every reasonable effort has been made to ensure that this document is correct at GOYDER the time of publication, the State of South Australia and its agencies, instrumentalities, employees and contractors disclaim any and all liability to any person in respect to anything or the consequence of anything done or omitted to be done in reliance upon the whole or any part of this document. -

Aboriginal Research Partnerships 26 April 2007 Fiona Haslam Mckenzie DKCRC Partners ‘Walking Together, Working Together’: Aboriginal Research Partnerships

21 Attracting and retaining skilled and professional staff in remote locations Attracting and retaining skilled professional staff Report ‘Walking together, working together’: Jocelyn Davies Aboriginal research partnerships 26 April 2007 Fiona Haslam McKenzie DKCRC Partners ‘Walking together, working together’: Aboriginal research partnerships Jocelyn Davies April 2007 Contributing author information Jocelyn Davies leads the Livelihoods inLand™ project for Desert Knowledge Cooperative Research Centre. She works as a geographer and principal research scientist for CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems, based in Alice Springs. Desert Knowledge CRC Report Number 26 Information contained in this publication may be copied or reproduced for study, research, information or educational purposes, subject to inclusion of an acknowledgement of the source. ISBN: 1 74158 052 8 (Online copy) ISSN: 1832 6684 Citation Davies J 2007, ‘Walking together, working together’: Aboriginal research partnerships, DKCRC Report 26, Desert Knowledge Cooperative Research Centre, Alice Springs. The Desert Knowledge Cooperative Research Centre is an unincorporated joint venture with 28 partners whose mission is to develop and disseminate an understanding of sustainable living in remote desert environments, deliver enduring regional economies and livelihoods based on Desert Knowledge, and create the networks to market this knowledge in other desert lands. For additional information please contact Desert Knowledge CRC Publications Officer PO Box 3971 Alice Springs NT 0871 Australia Telephone +61 8 8959 6000 Fax +61 8 8959 6048 www.desertknowledgecrc.com.au © Desert Knowledge CRC 2007 II Desert Knowledge CRC ‘Walking together, working together’: Aboriginal research partnerships Contents List of boxes IV List of shortened forms V Acknowledgements VI Key messages VII Summary IX 1. Introduction 1 2. -

Richness of Plants, Birds and Mammals Under the Canopy of Ramorinoa Girolae, an Endemic and Vulnerable Desert Tree Species

BOSQUE 38(2): 307-316, 2017 DOI: 10.4067/S0717-92002017000200008 Richness of plants, birds and mammals under the canopy of Ramorinoa girolae, an endemic and vulnerable desert tree species Riqueza de plantas, aves y mamíferos bajo el dosel de Ramorinoa girolae, una especie arbórea endémica y vulnerable del desierto Valeria E Campos a,b*, Viviana Fernández Maldonado a,b*, Patricia Balmaceda a, Stella Giannoni a,b,c a Interacciones Biológicas del Desierto (INTERBIODES), Av. I. de la Roza 590 (O), J5402DCS Rivadavia, San Juan, Argentina. *Corresponding author: b CIGEOBIO, UNSJ CONICET, Universidad Nacional de San Juan- CUIM, Av. I. de la Roza 590 (O), J5402DCS Rivadavia, San Juan, Argentina, phone 0054-0264-4260353 int. 402, [email protected], [email protected] c IMCN, FCEFN, Universidad Nacional de San Juan- España 400 (N), 5400 Capital, San Juan, Argentina. SUMMARY Dominant woody vegetation in arid ecosystems supports different species of plants and animals largely dependent on the existence of these habitats for their survival. The chica (Ramorinoa girolae) is a woody leguminous tree endemic to central-western Argentina and categorized as vulnerable. We evaluated 1) richness of plants, birds and mammals associated with the habitat under its canopy, 2) whether richness is related to the morphological attributes and to the features of the habitat under its canopy, and 3) behavior displayed by birds and mammals. We recorded presence/absence of plants under the canopy of 19 trees in Ischigualasto Provincial Park. Moreover, we recorded abundance of birds and mammals and signs of mammal activity using camera traps.