Combating International Organized Crime: Evaluating Current Authorities, Tools, and Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gangs Beyond Borders

Gangs Beyond Borders California and the Fight Against Transnational Organized Crime March 2014 Kamala D. Harris California Attorney General Gangs Beyond Borders California and the Fight Against Transnational Organized Crime March 2014 Kamala D. Harris California Attorney General Message from the Attorney General California is a leader for international commerce. In close proximity to Latin America and Canada, we are a state laced with large ports and a vast interstate system. California is also leading the way in economic development and job creation. And the Golden State is home to the digital and innovation economies reshaping how the world does business. But these same features that benefit California also make the state a coveted place of operation for transnational criminal organizations. As an international hub, more narcotics, weapons and humans are trafficked in and out of California than any other state. The size and strength of California’s economy make our businesses, financial institutions and communities lucrative targets for transnational criminal activity. Finally, transnational criminal organizations are relying increasingly on cybercrime as a source of funds – which means they are frequently targeting, and illicitly using, the digital tools and content developed in our state. The term “transnational organized crime” refers to a range of criminal activity perpetrated by groups whose origins often lie outside of the United States but whose operations cross international borders. Whether it is a drug cartel originating from Mexico or a cybercrime group out of Eastern Europe, the operations of transnational criminal organizations threaten the safety, health and economic wellbeing of all Americans, and particularly Californians. -

Gang Project Brochure Pg 1 020712

Salt Lake Area Gang Project A Multi-Jurisdictional Gang Intelligence, Suppression, & Diversion Unit Publications: The Project has several brochures available free of charge. These publications Participating Agencies: cover a variety of topics such as graffiti, gang State Agencies: colors, club drugs, and advice for parents. Local Agencies: Utah Dept. of Human Services-- Current gang-related crime statistics and Cottonwood Heights PD Div. of Juvenile Justice Services historical trends in gang violence are also Draper City PD Utah Dept. of Corrections-- available. Granite School District PD Law Enforcement Bureau METRO Midvale City PD Utah Dept. of Public Safety-- GANG State Bureau of Investigation Annual Gang Conference: The Project Murray City PD UNIT Salt Lake County SO provides an annual conference open to service Salt Lake County DA Federal Agencies: providers, law enforcement personnel, and the SHOCAP Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, community. This two-day event, held in the South Salt Lake City PD Firearms, and Explosives spring, covers a variety of topics from Street Taylorsville PD United States Attorney’s Office Survival to Gang Prevention Programs for Unified PD United States Marshals Service Schools. Goals and Objectives commands a squad of detectives. The The Salt Lake Area Gang Project was detectives duties include: established to identify, control, and prevent Suppression and street enforcement criminal gang activity in the jurisdictions Follow-up work on gang-related cases covered by the Project and to provide Collecting intelligence through contacts intelligence data and investigative assistance to with gang members law enforcement agencies. The Project also Assisting local agencies with on-going provides youth with information about viable investigations alternatives to gang membership and educates Answering law-enforcement inquiries In an emergency, please dial 911. -

The U.S. Homeland Security Role in the Mexican War Against Drug Cartels

THE U.S. HOMELAND SECURITY ROLE IN THE MEXICAN WAR AGAINST DRUG CARTELS HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT, INVESTIGATIONS, AND MANAGEMENT OF THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TWELFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION MARCH 31, 2011 Serial No. 112–14 Printed for the use of the Committee on Homeland Security Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 72–224 PDF WASHINGTON : 2012 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY PETER T. KING, New York, Chairman LAMAR SMITH, Texas BENNIE G. THOMPSON, Mississippi DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California LORETTA SANCHEZ, California MIKE ROGERS, Alabama SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas HENRY CUELLAR, Texas GUS M. BILIRAKIS, Florida YVETTE D. CLARKE, New York PAUL C. BROUN, Georgia LAURA RICHARDSON, California CANDICE S. MILLER, Michigan DANNY K. DAVIS, Illinois TIM WALBERG, Michigan BRIAN HIGGINS, New York CHIP CRAVAACK, Minnesota JACKIE SPEIER, California JOE WALSH, Illinois CEDRIC L. RICHMOND, Louisiana PATRICK MEEHAN, Pennsylvania HANSEN CLARKE, Michigan BEN QUAYLE, Arizona WILLIAM R. KEATING, Massachusetts SCOTT RIGELL, Virginia VACANCY BILLY LONG, Missouri VACANCY JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania BLAKE FARENTHOLD, Texas MO BROOKS, Alabama MICHAEL J. RUSSELL, Staff Director/Chief Counsel KERRY ANN WATKINS, Senior Policy Director MICHAEL S. TWINCHEK, Chief Clerk I. LANIER AVANT, Minority Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT, INVESTIGATIONS, AND MANAGEMENT MICHAEL T. -

La Familia Drug Cartel: Implications for U.S-Mexican Security

Visit our website for other free publication downloads http://www.StrategicStudiesInstitute.army.mil/ To rate this publication click here. STRATEGIC STUDIES INSTITUTE The Strategic Studies Institute (SSI) is part of the U.S. Army War College and is the strategic-level study agent for issues related to national security and military strategy with emphasis on geostrate- gic analysis. The mission of SSI is to use independent analysis to conduct strategic studies that develop policy recommendations on: • Strategy, planning, and policy for joint and combined employment of military forces; • Regional strategic appraisals; • The nature of land warfare; • Matters affecting the Army’s future; • The concepts, philosophy, and theory of strategy; and • Other issues of importance to the leadership of the Army. Studies produced by civilian and military analysts concern topics having strategic implications for the Army, the Department of De- fense, and the larger national security community. In addition to its studies, SSI publishes special reports on topics of special or immediate interest. These include edited proceedings of conferences and topically-oriented roundtables, expanded trip re- ports, and quick-reaction responses to senior Army leaders. The Institute provides a valuable analytical capability within the Army to address strategic and other issues in support of Army par- ticipation in national security policy formulation. LA FAMILIA DRUG CARTEL: IMPLICATIONS FOR U.S-MEXICAN SECURITY George W. Grayson December 2010 The views expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. -

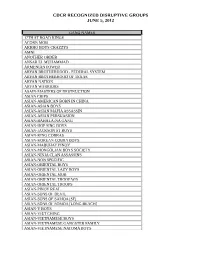

Cdcr Recognized Disruptive Groups June 5, 2012

CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 GANG NAMES 17TH ST ROAD KINGS ACORN MOB AKRHO BOYS CRAZZYS AMNI ANOTHER ORDER ANSAR EL MUHAMMAD ARMENIAN POWER ARYAN BROTHERHOOD - FEDERAL SYSTEM ARYAN BROTHERHOOD OF TEXAS ARYAN NATION ARYAN WARRIORS ASAIN-MASTERS OF DESTRUCTION ASIAN CRIPS ASIAN-AMERICAN BORN IN CHINA ASIAN-ASIAN BOYS ASIAN-ASIAN MAFIA ASSASSIN ASIAN-ASIAN PERSUASION ASIAN-BAHALA-NA GANG ASIAN-HOP SING BOYS ASIAN-JACKSON ST BOYS ASIAN-KING COBRAS ASIAN-KOREAN COBRA BOYS ASIAN-MABUHAY PINOY ASIAN-MONGOLIAN BOYS SOCIETY ASIAN-NINJA CLAN ASSASSINS ASIAN-NON SPECIFIC ASIAN-ORIENTAL BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL LAZY BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL MOB ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOP W/S ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOPS ASIAN-PINOY REAL ASIAN-SONS OF DEVIL ASIAN-SONS OF SAMOA [SF] ASIAN-SONS OF SOMOA [LONG BEACH] ASIAN-V BOYS ASIAN-VIET CHING ASIAN-VIETNAMESE BOYS ASIAN-VIETNAMESE GANGSTER FAMILY ASIAN-VIETNAMESE NATOMA BOYS CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 ASIAN-WAH CHING ASIAN-WO HOP TO ATWOOD BABY BLUE WRECKING CREW BARBARIAN BROTHERHOOD BARHOPPERS M.C.C. BELL GARDENS WHITE BOYS BLACK DIAMONDS BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLE BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLES NATION BLACK GANGSTERS BLACK INLAND EMPIRE MOB BLACK MENACE MAFIA BLACK P STONE RANGER BLACK PANTHERS BLACK-NON SPECIFIC BLOOD-21 MAIN BLOOD-916 BLOOD-ATHENS PARK BOYS BLOOD-B DOWN BOYS BLOOD-BISHOP 9/2 BLOOD-BISHOPS BLOOD-BLACK P-STONE BLOOD-BLOOD STONE VILLAIN BLOOD-BOULEVARD BOYS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER [LOT BOYS] BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-BELHAVEN BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-INCKERSON GARDENS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-NICKERSON -

Research Conferences on Organised Crime at the Bundeskriminalamt in Germany Conferences Research Research Conferences on Organised Crime 2013 – 2015

Polizei+Forschung 48 Content Edited by Since 2008 the yearly research conferences in Germany focusing on organised crime have established a European-wide forum that enables international exchange bet- Ursula Töttel ween academics and practitioners from law enforcement agencies. The event is hos- ted each year by the Bundeskriminalamt together with its research partners of the Gergana Bulanova-Hristova “Research Network on Organised Crime” from the United Kingdom, Sweden and the Netherlands. To date, there have been participants from 23 European countries and the United States. The conferences have received financial support from the EU Gerhard Flach since 2010. This book entails summaries of the speeches hold on the conferences from 2013 until 2015 and contributions from the speakers on selected topics in the field of organised crime. Research Conferences on Organised Crime at the Zum Inhalt Die jährlichen Forschungskonferenzen in Deutschland zum Thema Organisierte Bundeskriminalamt Kriminalität haben in den Jahren von 2008 bis 2015 ein anerkanntes Forum für den internationalen Austausch zwischen Wissenschaftlern und Praktikern aus Straf- verfolgungsbehörden geschaffen. Die Tagungen wurden durch das BKA in Zusam- in Germany menarbeit mit den Partnern aus dem „Research Network on Organised Crime“ aus dem Vereinigten Königreich, Schweden und den Niederlanden ausgerichtet und seit 2010 von der EU unterstützt. Auf den Konferenzen waren Teilnehmer aus insgesamt Vol. III 23 europäischen Ländern und den USA vertreten. Dieser Sammelband enthält Zusammenfassungen der Einzelvorträge der OK-For- schungskonferenzen von 2013 bis 2015 sowie Beiträge der Redner zu ausgewählten Transnational Organised Crime Themen aus dem Bereich der Organisierten Kriminalität. 2013 – 2015 This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. -

Glendale Police Department

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. ClPY O!.F qL'J;9{'jJ.!JL[/E • Police 'Department 'Davit! J. tJ1iompson CfUt! of Police J.1s preparea 6y tfit. (jang Investigation Unit -. '. • 148396 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this copyrighted material has been g~Qted bY l' . Giend a e C1ty Po11ce Department • to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permission of the copyright owner. • TABLEOFCON1ENTS • DEFINITION OF A GANG 1 OVERVIEW 1 JUVENILE PROBLEMS/GANGS 3 Summary 3 Ages 6 Location of Gangs 7 Weapons Used 7 What Ethnic Groups 7 Asian Gangs 8 Chinese Gangs 8 Filipino Gangs 10 Korean Gangs 1 1 Indochinese Gangs 12 Black Gangs 12 Hispanic Gangs 13 Prison Gang Influence 14 What do Gangs do 1 8 Graffiti 19 • Tattoo',;; 19 Monikers 20 Weapons 21 Officer's Safety 21 Vehicles 21 Attitudes 21 Gang Slang 22 Hand Signals 22 PROFILE 22 Appearance 22 Headgear 22 Watchcap 22 Sweatband 23 Hat 23 Shirts 23 PencHetons 23 Undershirt 23 T-Shirt 23 • Pants 23 ------- ------------------------ Khaki pants 23 Blue Jeans 23 .• ' Shoes 23 COMMON FILIPINO GANG DRESS 24 COMMON ARMENIAN GANG DRESS 25 COrvtMON BLACK GANG DRESS 26 COMMON mSPANIC GANG DRESS 27 ASIAN GANGS 28 Expansion of the Asian Community 28 Characteristics of Asian Gangs 28 Methods of Operations 29 Recruitment 30 Gang vs Gang 3 1 OVERVIEW OF ASIAN COMMUNITIES 3 1 Narrative of Asian Communities 3 1 Potential for Violence 32 • VIETNAMESE COMMUNITY 33 Background 33 Population 33 Jobs 34 Politics 34 Crimes 34 Hangouts 35 Mobility 35 Gang Identification 35 VIETNAMESE YOUTH GANGS 39 Tattoo 40 Vietnamese Background 40 Crimes 40 M.O. -

Breaking the Mexican Cartels: a Key Homeland Security Challenge for the Next Four Years

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2013 Breaking the Mexican Cartels: A Key Homeland Security Challenge for the Next Four Years Carrie F. Cordero Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] Georgetown Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper No. 13-028 This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1202 http://ssrn.com/abstract=2253889 81 UMKC L. Rev. 289-312 (2012) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Law Enforcement and Corrections Commons, Military, War, and Peace Commons, and the National Security Law Commons BREAKING THE MEXICAN CARTELS: A KEY HOMELAND SECURITY CHALLENGE FOR THE NEXT FOUR YEARS Carrie F. Cordero* Abstract Although accurate statistics are hard to come by, it is quite possible that 60,000 people have died in the last six-plus years as a result of armed conflict between the Mexican cartels and the Mexican government, amongst cartels fighting each other, and as a result of cartels targeting citizens. And this figure does not even include the nearly 40,000 Americans who die each year from using illegal drugs, much of which is trafficked through the U.S.-Mexican border. The death toll is only part of the story. The rest includes the terrorist tactics used by cartels to intimidate the Mexican people and government, an emerging point of view that the cartels resemble an insurgency, the threat—both feared and realized—of danger to Americans, and the understated policy approach currently employed by the U.S. -

The Dictionary Legend

THE DICTIONARY The following list is a compilation of words and phrases that have been taken from a variety of sources that are utilized in the research and following of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups. The information that is contained here is the most accurate and current that is presently available. If you are a recipient of this book, you are asked to review it and comment on its usefulness. If you have something that you feel should be included, please submit it so it may be added to future updates. Please note: the information here is to be used as an aid in the interpretation of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups communication. Words and meanings change constantly. Compiled by the Woodman State Jail, Security Threat Group Office, and from information obtained from, but not limited to, the following: a) Texas Attorney General conference, October 1999 and 2003 b) Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Security Threat Group Officers c) California Department of Corrections d) Sacramento Intelligence Unit LEGEND: BOLD TYPE: Term or Phrase being used (Parenthesis): Used to show the possible origin of the term Meaning: Possible interpretation of the term PLEASE USE EXTREME CARE AND CAUTION IN THE DISPLAY AND USE OF THIS BOOK. DO NOT LEAVE IT WHERE IT CAN BE LOCATED, ACCESSED OR UTILIZED BY ANY UNAUTHORIZED PERSON. Revised: 25 August 2004 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS A: Pages 3-9 O: Pages 100-104 B: Pages 10-22 P: Pages 104-114 C: Pages 22-40 Q: Pages 114-115 D: Pages 40-46 R: Pages 115-122 E: Pages 46-51 S: Pages 122-136 F: Pages 51-58 T: Pages 136-146 G: Pages 58-64 U: Pages 146-148 H: Pages 64-70 V: Pages 148-150 I: Pages 70-73 W: Pages 150-155 J: Pages 73-76 X: Page 155 K: Pages 76-80 Y: Pages 155-156 L: Pages 80-87 Z: Page 157 M: Pages 87-96 #s: Pages 157-168 N: Pages 96-100 COMMENTS: When this “Dictionary” was first started, it was done primarily as an aid for the Security Threat Group Officers in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ). -

National Gang Intelligence Center

UNCLASSIFIED//LAW ENFORCEMENT SENSITIVE National Gang Intelligence Center UNCLASSIFIED//LAW ENFORCEMENT SENSITIVE 1 UNCLASSIFIED//LAW ENFORCEMENT SENSITIVE This product was created by the National Gang Intelligence Center (NGIC) in cooperation with the state, local, and federal law enforcement agencies referenced on page 74. The information contained in this book represents a compilation of the information available to the NGIC and is strictly for intelligence purposes. For more information on the tattoos and gangs referenced in this book, please contact the NGIC by telephone at 703-414-8600 or by email at [email protected]. April 2010 UNCLASSIFIED//LAW ENFORCEMENT SENSITIVE 2 UNCLASSIFIED//LAW ENFORCEMENT SENSITIVE NATIONAL GANG INTELLIGENCE CENTER TABLE OF CONTENTS NORTHERN CALIFORNIA 4 - 19 NUESTRA FAMILIA 5 NORTEÑOS 9 CENTRAL CALIFORNIA 21 - 29 FRESNO BULLDOGS 21 SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA 31 - 78 MEXICAN MAFIA 33 SUREÑOS 43 * Sureño Gangs and Clicas 61 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 79 UNCLASSIFIED//LAW ENFORCEMENT SENSITIVE 3 UNCLASSIFIED//LAW ENFORCEMENT SENSITIVE NUESTRANUESTRA FAMILIAFAMILIA NORTENORTEÑÑOSOS UNCLASSIFIED//LAW ENFORCEMENT SENSITIVE 4 UNCLASSIFIED//LAW ENFORCEMENT SENSITIVE NATIONAL GANG INTELLIGENCE CENTER NUESTRA FAMILIA La Nuestra Familia (NF) formed in the 1960’s by a group of Hispanic inmates who were tired of suffering abuse at the hands of the California Mexican Mafia. NF has a written constitution and an organized hierarchy that oversees Norteño gangs in the state of California. A large and structured criminal organization, NF is heavily active in drug sales, murder, and a host of other illicit activities. The parent organization of Norteños, NF recruits its members largely from Norteño gangs; for this reason, NF members may display Norteño tattoos, specifically, the words North or Norte; the word “ene” (Spanish for N), and variations of the number 14. -

Ed 393 622 Author Title Report No Pub Date Note

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 393 622 RC 020 496 AUTHOR Moore, Joan W. TITLE Going Down to the Barrio: Homeboys and Homegirls in Change. REPORT NO ISBN-0-87722-855-8 PUB DATE 91 NOTE 187p. AVAILABLE FROM Temple University Press, Broad & Oxford Streets, Philadelphia, PA 19122 (cloth: ISBN-0-87722-854-X, $39.95; paperback: ISBN-0-87722-855-8, $18.95). PUB TYPE Books (010) Reports Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adolescent Development; Adolescents; Delinquency; Economic Factors; Family Life; *Juvenile Gangs; Life Style; Mexican Americans; Neighborhoods; Participatory Research; *Social Change; *Socialization; *Subcultures; Substance Abuse; Urban Youth; Violence; Young Adults; *Youth Problems IDENTIFIERS Barrios; *California (East Los Angeles); *Chicanos ABSTRACT This book traces the histories of two Chicano gangs in East Los Angeles since the early 1940s, when common gang stereotypes were created by the media and law enforcement agencies. In an unusual collaborative effort, researchers worked with former gang members to make contact with and interview members of various "cliques" (cohorts) of the White Fence and El Hoyo Maravilla gangs (male gangs), as well as female gangs in the same neighborhoods. Interviews were conducted with 156 adult men and women; about 40 percent had joined the gangs in the 1940s and early 1950s, while the rest had been'active in recent years. Data are set in the context of economic and social chaages in the barrios between the 1950s and the 1970s-80s. Data reveal that in the later era, gangs had become more institutionalized, were more influential in members' lives, and had become more deviant. -

Smoke, Mirrors, and the Joker in the Pack: on Transitioning to Democracy and the Rule of Law in Post-Soviet Armenia

SMOKE, MIRRORS, AND THE JOKER IN THE PACK: ON TRANSITIONING TO DEMOCRACY AND THE RULE OF LAW IN POST-SOVIET ARMENIA Karen E. Bravo* I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................. 492 A. TransitioningFrom "Them" to "Us"......................... 492 B. Armenia's Transition to Democracy.......................... 494 II. ARMENIA AFTER THE U.S.S.R .................................... 499 A. Geography and History of Armenia .......................... 500 B. Post-Soviet PoliticalDevelopments; Conflicts & Consequences.............................................................. 501 C. PoliticalLeaders and Assassins................................ 503 D. Apparent Progress...................................................... 506 Assistant Professor of Law, Indiana University School of Law-Indianapolis; L.L.M. New York University School of Law; J.D. Columbia University School of Law; B.A. University of the West Indies. From July 2002 to March 2003, the Author lived and worked in Armenia as a Rule of Law Liaison with the American Bar Association Central European and Eurasian Law Initiative (ABA/CEELI), a project of the International Law Section of the American Bar Association and a United States Agency for International Development (USAID) funded project. She is grateful to Elizabeth Defeis of Seton Hall University School of Law, Kevin Johnson of the University of California-Davis School of Law, Ndiva Kofele-Kale of Southern Methodist University Dedman School of Law, George Edwards, Maria Pab6n Lopez, and Florence Wagman Roisman of Indiana University School of Law-Indianapolis, Enid Trucios-Haynes of Louis D. Brandeis School of Law, and the participants of the January 2006 Mid-Atlantic People of Color Legal Scholarship Conference for their comments on earlier drafts. Any errors of fact or judgment are the Author's. This Article is dedicated to the Author's Armenian friends and former colleagues who work passionately for Armenia's future.