Richard Wilson Revisited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eighteenth-Century English and French Landscape Painting

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2018 Common ground, diverging paths: eighteenth-century English and French landscape painting. Jessica Robins Schumacher University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Schumacher, Jessica Robins, "Common ground, diverging paths: eighteenth-century English and French landscape painting." (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3111. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/3111 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMON GROUND, DIVERGING PATHS: EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH AND FRENCH LANDSCAPE PAINTING By Jessica Robins Schumacher B.A. cum laude, Vanderbilt University, 1977 J.D magna cum laude, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville, 1986 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art (C) and Art History Hite Art Department University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2018 Copyright 2018 by Jessica Robins Schumacher All rights reserved COMMON GROUND, DIVERGENT PATHS: EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH AND FRENCH LANDSCAPE PAINTING By Jessica Robins Schumacher B.A. -

OSWESTRY Where Shropshire Meets Wales

FREE MAPS What to see, do & where to stay 2019 OSWESTRY Where Shropshire meets Wales Surprising - Historic - Friendly P L A C T H E R O I F B • • 1893 1918 W I N L E F W www.borderland-breaks.co.uk OswestryTourism R E D O Do you like surprises? Then visit Oswestry... This small border town on the edge of Shropshire and the brink of Wales may not be familiar to you and certainly, many of the visitors that arrive here say: What a surprise Oswestry is – there is so much to see and explore. We’ll have to come back again. Information at Visitor & Exhibition So let us surprise you and tempt you to visit. Take a look through our Centre brochure and we hope it will make you want to visit Oswestry – 2 Church Terrace where Shropshire meets Wales. Oswestry SY11 2TE Firstly, take a spectacular, dramatic and What’s on? Let us entertain you. We say 01691 662753 mysterious 3000 year old hill fort that was Oswestry is ‘Fest Fabulous’ because there are the beginning of Oswestry and add a so many different events and the variety is Photo thriving town that still has a weekly market. impressive. Don’t miss the free town centre Reference: There’s a lively café culture which, combined events which are in the streets and our Front cover: with the eclectic mix of small independent beautiful park. The Hot Air Balloon Carnival, Hot air balloon over shops, entices visitors from miles around. Food and Drink Festival and Christmas Live Oswestry Town Then scatter a few castles around; sprinkle are the main happenings there. -

Constable, Gainsborough, Turner and the Making of Landscape

CONSTABLE, GAINSBOROUGH, TURNER AND THE MAKING OF LANDSCAPE THE JOHN MADEJSKI FINE ROOMS 8 December 2012 – 17 February 2013 This December an exhibition of works by the three towering figures of English landscape painting, John Constable RA, Thomas Gainsborough RA and JMW Turner RA and their contemporaries, will open in the John Madejski Fine Rooms and the Weston Rooms. Constable, Gainsborough, Turner and the Making of Landscape will explore the development of the British School of Landscape Painting through the display of 120 works of art, comprising paintings, prints, books and archival material. Since the foundation of the Royal Academy of Arts in 1768, its Members included artists who were committed to landscape painting. The exhibition draws on the Royal Academy’s Collection to underpin the shift in landscape painting during the 18 th and 19 th centuries. From Founder Member Thomas Gainsborough and his contemporaries Richard Wilson and Paul Sandby, to JMW Turner and John Constable, these landscape painters addressed the changing meaning of ‘truth to nature’ and the discourses surrounding the Beautiful, the Sublime and the Picturesque. The changing style is represented by the generalised view of Gainsborough’s works and the emotionally charged and sublime landscapes by JMW Turner to Constable’s romantic scenes infused with sentiment. Highlights include Gainsborough’s Romantic Landscape (c.1783), and a recently acquired drawing that was last seen in public in 1950. Constable’s two great landscapes of the 1820s, The Leaping Horse (1825) and Boat Passing a Lock (1826) will be hung alongside Turner’s brooding diploma work, Dolbadern Castle (1800). -

Chapter Eleven

Chapter eleven he greater opportunities for patronage and artistic fame that London could offer lured many Irish artists to seek their fortune. Among landscape painters, George Barret was a founding Tmember of the Royal Academy; Robert Carver pursued a successful career painting scenery for the London theatres and was elected President of the Society of Artists while, even closer to home, Roberts’s master George Mullins relocated to London in 1770, a year after his pupil had set up on his own in Dublin – there may even have been some connection between the two events. The attrac- tions of London for a young Irish artist were manifold. The city offered potential access to ever more elevated circles of patronage and the chance to study the great collections of old masters. Even more fundamental was the febrile artistic atmosphere that the creation of the Royal Academy had engen- dered; it was an exciting time to be a young ambitious artist in London. By contrast, on his arrival in Dublin in 1781, the architect James Gandon was dismissive of the local job prospects: ‘The polite arts, or their professors, can obtain little notice and less encouragement amidst such conflicting selfish- ness’, a situation which had led ‘many of the highly gifted natives...[to] seek for personal encourage- ment and celebrity in England’.1 Balancing this, however, Roberts may have judged the market for landscape painting in London to be adequately supplied. In 1769, Thomas Jones, himself at an early stage at his career, surveyed the scene: ‘There was Lambert, & Wilson, & Zuccarelli, & Gainsborough, & Barret, & Richards, & Marlow in full possession of landscape business’.2 Jones concluded that ‘to push through such a phalanx required great talents, great exertions, and above all great interest’.3 As well as the number of established practitioners in the field there was also the question of demand. -

Lowell Libson Limited

LOWELL LI BSON LTD 2 0 1 0 LOWELL LIBSON LIMITED BRITISH PAINTINGS WATERCOLOURS AND DRAWINGS 3 Clifford Street · Londonw1s 2lf +44 (0)20 7734 8686 · [email protected] www.lowell-libson.com LOWELL LI BSON LTD 2 0 1 0 Our 2010 catalogue includes a diverse group of works ranging from the fascinating and extremely rare drawings of mid seventeenth century London by the Dutch draughtsman Michel 3 Clifford Street · Londonw1s 2lf van Overbeek to the small and exquisitely executed painting of a young geisha by Menpes, an Australian, contained in the artist’s own version of a seventeenth century Dutch frame. Telephone: +44 (0)20 7734 8686 · Email: [email protected] Sandwiched between these two extremes of date and background, the filling comprises Website: www.lowell-libson.com · Fax: +44 (0)20 7734 9997 some quintessentially British works which serve to underline the often forgotten international- The gallery is open by appointment, Monday to Friday ism of ‘British’ art and patronage. Bellucci, born in the Veneto, studied in Dalmatia, and worked The entrance is in Old Burlington Street in Vienna and Düsseldorf before being tempted to England by the Duke of Chandos. Likewise, Boitard, French born and Parisian trained, settled in London where his fluency in the Rococo idiom as a designer and engraver extended to ceramics and enamels. Artists such as Boitard, in the closely knit artistic community of London, provided the grounding of Gainsborough’s early In 2010 Lowell Libson Ltd is exhibiting at: training through which he synthesised -

Wales & the Cotswolds

WALES & THE COTSWOLDS JULY 3 – JULY 22, 2015 | £3,199* per person Our tour includes one of the most in-depth explorations of Wales and the Welsh borderlands available: some the best of the Cotswolds; a visit to the famous Ironbridge Museum, otherwise known as the Valley of the Industrial Revolution; and finishing at Highclere Castle, better known as Downton Abbey. Our routing is always via the most picturesque and varied countryside, concentrating on Britain’s heritage wherever possible — its ruins, castles, palaces, abbeys and stately homes containing many interesting and varied collections, many of which have featured in movies and familiar TV series. The great thing about the majority of these wonderful attractions in the countryside is that they are nearly all also museums in themselves. We visit some of the loveliest Cotswold villages, with their gorgeous thatched cottages and honey-coloured stone. In addition to history, our emphasis throughout is spectacular scenery, amazingly different architecture due to both the construction periods and the use of local building materials (mostly due to the astonishingly diverse geology of Britain), and glorious gardens, so that the entire trip is a photographer’s dream. We include up to 35 different attractions with no ‘optional extras’. We stay in lovely hotels with great food, sometimes in very small places, where the emphasis is more on local charm than on North American-style modernization! INCLUDED IN THE PRICE Airport transfer for those arriving with the majority of the group • Accommodation and transportation • Breakfasts and dinners as specified • Admission to all attractions as per the detailed itinerary • Escort throughout The tour is escorted by Maggie Rodgers who has taught Travel courses for Continuing Education in Vancouver, Surrey and White Rock, British Columbia, for several years. -

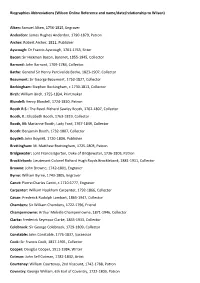

Biographies Abbreviations (Wilson Online Reference and Name/Date/Relationship to Wilson)

Biographies Abbreviations (Wilson Online Reference and name/date/relationship to Wilson) Alken: Samuel Alken, 1756-1815, Engraver Anderdon: James Hughes Anderdon, 1790-1879, Patron Archer: Robert Archer, 1811, Publisher Ayscough: Dr Francis Ayscough, 1701-1763, Sitter Bacon: Sir Hickman Bacon, Baronet, 1855-1945, Collector Barnard: John Barnard, 1709-1784, Collector. Bathe: General Sir Henry Percival de Bathe, 1823-1907, Collector Beaumont: Sir George Beaumont, 1753-1827, Collector Beckingham: Stephen Beckingham, c.1730-1813, Collector Birch: William Birch, 1755-1834, Printmaker Blundell: Henry Blundell, 1724-1810, Patron Booth R.S.: The Revd. Richard Sawley Booth, 1762-1807, Collector Booth, E.: Elizabeth Booth, 1763-1819, Collector Booth, M: Marianne Booth, Lady Ford, 1767-1849, Collector Booth: Benjamin Booth, 1732-1807, Collector Boydell: John Boydell, 1720-1804, Publisher Brettingham: M. Matthew Brettingham, 1725-1803, Patron Bridgewater: Lord Francis Egerton, Duke of Bridgewater, 1736-1803, Patron Brocklebank: Lieutenant Colonel Richard Hugh Royds Brocklebank, 1881-1911, Collector Browne: John Browne, 1742-1801, Engraver Byrne: William Byrne, 1743-1805, Engraver Canot: Pierre-Charles Canot, c.1710-1777, Engraver Carpenter: William Hookham Carpenter, 1792-1866, Collector Cavan: Frederick Rudolph Lambart, 1865-1947, Collector Chambers: Sir William Chambers, 1722-1796, Friend Champernowne: Arthur Melville Champernowne, 1871-1946, Collector Clarke: Frederick Seymour Clarke, 1855-1933, Collector Colebrook: Sir George Colebrook, 1729-1809, Collector Constable: John Constable, 1776-1837, Successor Cook: Sir Francis Cook, 1817-1901, Collector Cooper: Douglas Cooper, 1911-1984, Writer Cotman: John Sell Cotman, 1782-1842, Artist Courtenay: William Courtenay, 2nd Viscount, 1742-1788, Patron Coventry: George William, 6th Earl of Coventry, 1722-1809, Patron Dartmouth: William Legge, 2nd Earl of Dartmouth, 1731-1801, Patron Daulby: Daniel Daulby, d. -

18 April 2019. Dear , ATISN 13078 – Freedom of Information Request

18 April 2019. Dear , ATISN 13078 – Freedom of Information Request – Caerphilly Castle. Thank you for your request, which was received on 21st March 2019, about Caerphilly Castle. The information you requested is enclosed. A copy of all proposals, in their current form for the Castle, its grounds and waters (also referred to elsewhere as the ‘masterplan’). Please find attached the current Part A and Part B Masterplan documents. It is important to stress that this is a broad framework that helps capture a range of outline projects, themes and ideas that will be explored through formal business and option appraisal arrangements over the next three years. We will not necessarily be pursuing all of the projects, or in the form that they are suggested, in the plan. In as full detail as possible the planned works to the lakes and moats and the purpose of these works. The only current planned works is to undertake annual Canadian Pondweed clearance between 3rd – 21st June and 30th Sept – 18th October 2019, as agreed with the Caerphilly Angling Club and NRW at a meeting held on 20th December 2018 with Cadw. These works are necessary to control the invasive, rapid weed growth in order to maintain the biodiversity (i.e. the health of the moat and the wildlife living within in it) and the aesthetics of the moat. No further works are planned beyond this presently. 1 Any formal risk-assessment in respect of the issue of back to back fishing on the Northern Lake walkway. Cadw have not undertaken any formal risk assessment in relation to the above. -

Llangollen: Understanding Urban Character

Llangollen: Understanding Urban Character Cadw Welsh Government Plas Carew Unit 5/7 Cefn Coed Parc Nantgarw Cardiff CF15 7QQ Telephone: 01443 33 6000 Email: [email protected] First published by Cadw in 2016 Print ISBN 978 1 85760 377 4 Digital ISBN 978 1 85760 378 1 © Crown Copyright 2016, Cadw, Welsh Government WG26217 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or e-mail: [email protected] Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought, including the Denbighshire Archives, Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru/National Library of Wales, Lockmaster Maps, National Buildings Record, National Monuments Record of Wales, Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales, The Francis Frith Collection, and the Welsh Government (Cadw). Cadw is the Welsh Government’s historic environment service, working for an accessible and well-protected historic environment. Mae’r ddogfen yma hefyd ar gael yn Gymraeg. This document is also available in Welsh. Cadw is the Welsh Government’s historic environment service, working for an accessible and well-protected historic environment. Cadw Welsh Government Plas Carew Unit 5/7 Cefn Coed Parc Nantgarw Cardiff CF15 7QQ Llangollen: Understanding Urban Character 1 Acknowledgements The Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales (RCAHMW) provided the photography for this study which can be accessed via Coflein at www.coflein.gov.uk. -

Wales Heritage Interpretation Plan

TOUCH STONE GREAT EXPLANATIONS FOR PEOPLE AT PLACES Cadw Pan-Wales heritage interpretation plan Wales – the first industrial nation Ysgogiad DDrriivviinngg FFoorrcceess © Cadw, Welsh Government Interpretation plan October 2011 Cadw Pan-Wales heritage interpretation plan Wales – the first industrial nation Ysgogiad Driving Forces Interpretation plan Prepared by Touchstone Heritage Management Consultants, Red Kite Environment and Letha Consultancy October 2011 Touchstone Heritage Management Consultants 18 Rose Crescent, Perth PH1 1NS, Scotland +44/0 1738 440111 +44/0 7831 381317 [email protected] www.touchstone-heritage.co.uk Michael Hamish Glen HFAHI FSAScot FTS, Principal Associated practice: QuiteWrite Cadw – Wales – the first industrial nation / Interpretation plan i ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Contents 1 Foreword 1 2 Introduction 3 3 The story of industry in Wales 4 4 Our approach – a summary 13 5 Stakeholders and initiatives 14 6 Interpretive aim and objectives 16 7 Interpretive themes 18 8 Market and audiences 23 9 Our proposals 27 10 Interpretive mechanisms 30 11 Potential partnerships 34 12 Monitoring and evaluation 35 13 Appendices: Appendix A: Those consulted 38 Appendix B: The brief in full 39 Appendix C: National Trust market segments 41 Appendix D: Selected people and sites 42 The illustration on the cover is part of a reconstruction drawing of Blaenavon Ironworks by Michael -

2003/1 (6) 1 Art on the Line

Art on the line EXHIBITION REVIEW: Thomas Jones 1742-1803 Jonathan Blackwood School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Glamorgan, Pontypridd, CF37 1DL, Wales [email protected] This magnificent monographic show, curated roots in rural mid Wales as well as his train- by Ann Sumner, will do much to introduce ing under Wilson and the dramatic impact gallery visitors to the work of Thomas Jones that Italy, and Naples in particular, was to and restore him to his rightful place as an have on his work. The culmination of his important figure in UK landscape painting, in years in London and his membership of the the second half of the eighteenth century. Society of Artists was The Bard of 1774. Jones was born in Radnorshire in 1742 Based on Thomas Gray’s poem, published in and initially seemed destined for a career as 1757, the painting fuses Wilsonian land- a clergyman. However, a change of heart scape ideas with a dramatic staging of saw him train as an artist under Richard Edward I’s massacre of the Welsh bards Wilson (1761-63), and then exhibit as a under an apocalyptic sky. The painting is a member of the Society of Artists from 1766 striking and arresting summary of the rapid onwards. A decade later, Jones left the and capable development of Jones’ talent in United Kingdom for some years in Italy, the first years of his career. spent mainly in Rome and Naples. He came Just over half the exhibits are devoted to back in 1783 on the death of his father and Jones’ years in Italy from 1776-83. -

1 Exhibition Abbreviations

Exhibition Abbreviations (Wilson Online Reference abbreviations and titles/locations) Agnew 1926: Exhibition of English Landscapes in Aid of the Artists' Benevolent Institution, at Thomas Agnew and Sons Galleries. London, Thomas Agnew & Sons Agnew 1937: Coronation Exhibition of British Pictures. London, Thomas Agnew & Sons Amsterdam 1936: Twee Eeuwen Engelsche Kunst (Loan Exhibition of British Art). Amsterdam, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam 1965: De Engelse Aquarel uit de 18de Eeuw: Van Cozens tot Turner. Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet Arts Council 1951: Three Centuries of British Water-colours and Drawings. London, Festival of Britain Baltimore 1979-80: Eighteenth Century Master Drawings from the Ashmolean. Baltimore Museum of Art, USA Bangor 1925: Exhibition of Oil-Paintings by Richard Wilson, R.A., J.M.W. Turner, R.A, John Crome, Thomas Barker. Bangor, University College of North Wales BI 1814: Works by Hogarth, Gainsborough and Wilson lent to the British Institution. London, British Institution Birmingham 1948-49: Exhibition of Pictures by Richard Wilson and his Circle. Birmingham City Art Gallery Birmingham 1993: Canaletto and England. Birmingham City Art Gallery Brighton 1920: A Collection of Oil Paintings and Sketches by Richard Wilson, R.A. lent by Captain Richard Ford. Brighton, Fine Art Galleries Cardiff 2001: Wilson at Work: Techniques of an 18th Century Painter. Cardiff, Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales Cardiff, Manchester and London, 2003-4: Thomas Jones (1742-1803): An Artist Rediscovered. National Museum & Gallery, Cardiff, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester and National Gallery, London Constable Turner Gainsborough 2012: Constable, Gainsborough, Turner and the Making of Landscape: London, Royal Academy Conwy 2009: Richard Wilson: Life & Legacy. Conwy, Royal Cambrian Academy.