Film in Concert

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Winonan - 1990S

Winona State University OpenRiver The inonW an - 1990s The inonW an – Student Newspaper 12-17-1997 The inonW an Winona State University Follow this and additional works at: https://openriver.winona.edu/thewinonan1990s Recommended Citation Winona State University, "The inonW an" (1997). The Winonan - 1990s. 190. https://openriver.winona.edu/thewinonan1990s/190 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The inonW an – Student Newspaper at OpenRiver. It has been accepted for inclusion in The inonW an - 1990s by an authorized administrator of OpenRiver. For more information, please contact [email protected]. w NONA 1711 UNIVERS Ill RA F1 illinonan 3 0106 00362 4565 Wednesday, December 17, 1997 Volume 76, Issue 8 WSU may soon convert to "Laptop U" Baldwin By Lori Oliver Consultant Greg Peterson. option to buy the laptop before the the students' tution bill. The univer- the laptop university, but they do not too loud News Reporter Under the laptop university, stu- lease is up or at the time when the sity is concerned about students de- have all of the answers. Answers dents would be required to lease a lease expires. ciding to leave the university because won't be guaranteed until the univer- laptop computer from the university. Incoming freshman will lease on a they can't afford to pay the extra sity actually begins the process of On Monday and Tuesday Winona Three main phases are involved in three-year period, and the lease will money for the laptops. converting WSU to a laptop univer- for study this process. -

CITIZEN KANE by Herman J. Mankiewicz & Orson Welles PROLOGUE FADE IN

CITIZEN KANE by Herman J. Mankiewicz & Orson Welles PROLOGUE FADE IN: EXT. XANADU - FAINT DAWN - 1940 (MINIATURE) Window, very small in the distance, illuminated. All around this is an almost totally black screen. Now, as the camera moves slowly towards the window which is almost a postage stamp in the frame, other forms appear; barbed wire, cyclone fencing, and now, looming up against an early morning sky, enormous iron grille work. Camera travels up what is now shown to be a gateway of gigantic proportions and holds on the top of it - a huge initial "K" showing darker and darker against the dawn sky. Through this and beyond we see the fairy-tale mountaintop of Xanadu, the great castle a sillhouette as its summit, the little window a distant accent in the darkness. DISSOLVE: (A SERIES OF SET-UPS, EACH CLOSER TO THE GREAT WINDOW, ALL TELLING SOMETHING OF:) The literally incredible domain of CHARLES FOSTER KANE. Its right flank resting for nearly forty miles on the Gulf Coast, it truly extends in all directions farther than the eye can see. Designed by nature to be almost completely bare and flat - it was, as will develop, practically all marshland when Kane acquired and changed its face - it is now pleasantly uneven, with its fair share of rolling hills and one very good-sized mountain, all man-made. Almost all the land is improved, either through cultivation for farming purposes of through careful landscaping, in the shape of parks and lakes. The castle dominates itself, an enormous pile, compounded of several genuine castles, of European origin, of varying architecture - dominates the scene, from the very peak of the mountain. -

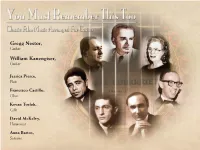

Gregg Nestor, William Kanengiser

Gregg Nestor, Guitar William Kanengiser, Guitar Jessica Pierce, Flute Francisco Castillo, Oboe Kevan Torfeh, Cello David McKelvy, Harmonica Anna Bartos, Soprano Executive Album Producers for BSX Records: Ford A. Thaxton and Mark Banning Album Produced by Gregg Nestor Guitar Arrangements by Gregg Nestor Tracks 1-5 and 12-16 Recorded at Penguin Recording, Eagle Rock, CA Engineer: John Strother Tracks 6-11 Recorded at Villa di Fontani, Lake View Terrace, CA Engineers: Jonathan Marcus, Benjamin Maas Digitally Edited and Mastered by Jonathan Marcus, Orpharian Recordings Album Art Direction: Mark Banning Mr. Nestor’s Guitars by Martin Fleeson, 1981 José Ramirez, 1984 & Sérgio Abreu, 1993 Mr. Kanengiser’s Guitar by Miguel Rodriguez, 1977 Special Thanks to the composer’s estates for access to the original scores for this project. BSX Records wishes to thank Gregg Nestor, Jon Burlingame, Mike Joffe and Frank K. DeWald for his invaluable contribution and oversight to the accuracy of the CD booklet. For Ilaine Pollack well-tempered instrument - cannot be tuned for all keys assuredness of its melody foreshadow the seriousness simultaneously, each key change was recorded by the with which this “concert composer” would approach duo sectionally, then combined. Virtuosic glissando and film. pizzicato effects complement Gold's main theme, a jaunty, kaleidoscopic waltz whose suggestion of a Like Korngold, Miklós Rózsa found inspiration in later merry-go-round is purely intentional. years by uniting both sides of his “Double Life” – the title of his autobiography – in a concert work inspired by his The fanfare-like opening of Alfred Newman’s ALL film music. Just as Korngold had incorporated themes ABOUT EVE (1950), adapted from the main title, pulls us from Warner Bros. -

Sheet Music of Flashdance What a Feeling Irene Cara Clarinet Quintet You Need to Signup, Download Music Sheet Notes in Pdf Format Also Available for Offline Reading

Flashdance What A Feeling Irene Cara Clarinet Quintet Sheet Music Download flashdance what a feeling irene cara clarinet quintet sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 6 pages partial preview of flashdance what a feeling irene cara clarinet quintet sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 5589 times and last read at 2021-09-25 21:31:46. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of flashdance what a feeling irene cara clarinet quintet you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Bass Clarinet Ensemble: Clarinet Quintet, Woodwind Quintet Level: Intermediate [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Flashdance What A Feeling Irene Cara String Quintet Flashdance What A Feeling Irene Cara String Quintet sheet music has been read 6183 times. Flashdance what a feeling irene cara string quintet arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-23 13:21:11. [ Read More ] Flashdance What A Feeling Irene Cara Brass Quintet Flashdance What A Feeling Irene Cara Brass Quintet sheet music has been read 4181 times. Flashdance what a feeling irene cara brass quintet arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-24 14:07:20. [ Read More ] Flashdance What A Feeling Irene Cara Sab Flashdance What A Feeling Irene Cara Sab sheet music has been read 2971 times. Flashdance what a feeling irene cara sab arrangement is for Early Intermediate level. -

Recital Theme: So You Think You Can Dance

Recital Theme: So You Think You Can Dance GENRE LEVEL SONG ALBUM / ARTIST Ballet Baby Age 2-3 Hooray For Chasse Wake Up And Wiggle/Marie Barnett Ballet Baby Age 2-3 Wacky Wallaby Waltz Put On Your Dancing Shoes/Joanie Bartels Ballet I - II Age 8-12 9 Dancing Princesses Ballet I - II Teen/Adult Dance Of The Hours From the opera La Gioconda/Amilcare Ponchielli Ballet II Age 8-10 7 Dancing Princesses Ballet II - III Age 10-12 Copelia Waltz Coppelia/Delibes Ballet II - III Teen/Adult Danse Napolitiane Swan Lake/Tchaikovsky Ballet III - IV Teen/Adult Dance of The Reed Flutes Nutcracker Suite/Tchaikovsky Ballet IV Teen/Adult Paquita Allegro Paquita/La Bayadere Ballet IV - V Teen/Adult Paquita Coda Paquita/La Bayadere Pre-Ballet I - II Age 5-6 Sugar Plum Fairies Nutcracker Suite/Tchaikovsky Pre-Ballet I - II Age 6-8 Little Swans Swan Lake/Tchaikovsky Hip Hop I Age 6-8 Pon De Replay Music of the Sun/Rihanna Hip Hop I Age 9-12 Get Up Step Up Soundtrack/Ciara Hip Hop I - II Age 6-8 Move It Like This Move It Like This/Baja Men Hip Hop I - II Age 8-12 1,2 Step Goodies/Ciara and Missy Elliott Hip Hop I - II Age 10-12 Get Up "Step Up" Soundtrack/Ciara Hip Hop "The Longest Yard" Soundtrack/Jung Tru,King Jacob I - II Teen/Adult Errtime and Nelly Hip Hop I - II Teen/Adult Switch Lost and Found/Will Smith Hip Hop I - II Adult Yeah Confessions/Usher Hip Hop II Adult Let It Go Heaven Sent/Keyshia Cole feat. -

BBC Four Programme Information

SOUND OF CINEMA: THE MUSIC THAT MADE THE MOVIES BBC Four Programme Information Neil Brand presenter and composer said, “It's so fantastic that the BBC, the biggest producer of music content, is showing how music works for films this autumn with Sound of Cinema. Film scores demand an extraordinary degree of both musicianship and dramatic understanding on the part of their composers. Whilst creating potent, original music to synchronise exactly with the images, composers are also making that music as discreet, accessible and communicative as possible, so that it can speak to each and every one of us. Film music demands the highest standards of its composers, the insight to 'see' what is needed and come up with something new and original. With my series and the other content across the BBC’s Sound of Cinema season I hope that people will hear more in their movies than they ever thought possible.” Part 1: The Big Score In the first episode of a new series celebrating film music for BBC Four as part of a wider Sound of Cinema Season on the BBC, Neil Brand explores how the classic orchestral film score emerged and why it’s still going strong today. Neil begins by analysing John Barry's title music for the 1965 thriller The Ipcress File. Demonstrating how Barry incorporated the sounds of east European instruments and even a coffee grinder to capture a down at heel Cold War feel, Neil highlights how a great composer can add a whole new dimension to film. Music has been inextricably linked with cinema even since the days of the "silent era", when movie houses employed accompanists ranging from pianists to small orchestras. -

BANG BANG? I GOT MINE! – David Bowie Em Um Western Italiano Fora Do Tempo E Do Espaço

IL MIO WEST: BANG BANG? I GOT MINE! – David Bowie em um western italiano fora do tempo e do espaço Tiago José Lemos Monteiro1 Tão diversa em termos de estilo quanto a discografia de David Bowie são as incursões do Camaleão pelo universo audiovisual. Passada a ressaca do sucesso estrondoso de Let's Dance (1983), e um pouco ecoando o caráter mezzo experimental, mezzo hermético, mezzo híbrido (pois apenas David Bowie autoriza subversões da lógica como esta das três metades) dos 1 Doutor em Comunicação pela Universidade Federal Fluminense, Mestre em Comunicação e Cultura pela Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (2006). Professor efetivo do Curso de Produção Cultural do Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia do Rio de Janeiro, responsável pelo Núcleo de Criação Audiovisual (NUCA). [email protected] álbuns que lançou nos anos de 1990, também os títulos que o cantor estrelou neste decênio aprofundam o caráter sui generis que atravessa obras como 1.Outside (1995) ou Earthling (1997). Nenhum filme sumariza melhor a esquizofrenia criativa do cantor e compositor inglês nos estertores do século passado do que Il mio west (Giovanni Veronesi, 1998), que já possuiria razões suficientes para ser considerado um tremendo alienígena audiovisual, mesmo sem a presença de David Bowie como um sádico vilão steampunk. Para melhor acessarmos o ponto fora da curva que Il mio West representa para o cinema italiano de gênero quanto para a filmografia de David Bowie, é preciso fazer uma breve digressão sobre os caminhos da indústria audiovisual na Itália durante a segunda metade do século XX. Mais ou menos à mesma época em que a narrativa clássica se consolidava nos Estados Unidos e o sistema de estúdios dava seus primeiros passos, a Itália já possuía tradição na produção de filmes caros e grandiosos, sobretudo nas modalidades do épico de verniz histórico, como Gli ultimi giorni di Pompei (Mario Caserini, 1913) e Cabiria (Giovanni Pastrone, 1914). -

Track 1 Juke Box Jury

CD1: 1959-1965 CD4: 1971-1977 Track 1 Juke Box Jury Tracks 1-6 Mary, Queen Of Scots Track 2 Beat Girl Track 7 The Persuaders Track 3 Never Let Go Track 8 They Might Be Giants Track 4 Beat for Beatniks Track 9 Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland Track 5 The Girl With The Sun In Her Hair Tracks 10-11 The Man With The Golden Gun Track 6 Dr. No Track 12 The Dove Track 7 From Russia With Love Track 13 The Tamarind Seed Tracks 8-9 Goldfinger Track 14 Love Among The Ruins Tracks 10-17 Zulu Tracks 15-19 Robin And Marian Track 18 Séance On A Wet Afternoon Track 20 King Kong Tracks 19-20 Thunderball Track 21 Eleanor And Franklin Track 21 The Ipcress File Track 22 The Deep Track 22 The Knack... And How To Get It CD5: 1978-1983 CD2: 1965-1969 Track 1 The Betsy Track 1 King Rat Tracks 2-3 Moonraker Track 2 Mister Moses Track 4 The Black Hole Track 3 Born Free Track 5 Hanover Street Track 4 The Wrong Box Track 6 The Corn Is Green Track 5 The Chase Tracks 7-12 Raise The Titanic Track 6 The Quiller Memorandum Track 13 Somewhere In Time Track 7-8 You Only Live Twice Track 14 Body Heat Tracks 9-14 The Lion In Winter Track 15 Frances Track 15 Deadfall Track 16 Hammett Tracks 16-17 On Her Majesty’s Secret Service Tracks 17-18 Octopussy CD3: 1969-1971 CD6: 1983-2001 Track 1 Midnight Cowboy Track 1 High Road To China Track 2 The Appointment Track 2 The Cotton Club Tracks 3-9 The Last Valley Track 3 Until September Track 10 Monte Walsh Track 4 A View To A Kill Tracks 11-12 Diamonds Are Forever Track 5 Out Of Africa Tracks 13-21 Walkabout Track 6 My Sister’s Keeper -

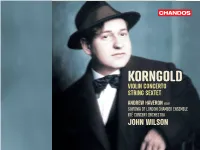

Korngold Violin Concerto String Sextet

KORNGOLD VIOLIN CONCERTO STRING SEXTET ANDREW HAVERON VIOLIN SINFONIA OF LONDON CHAMBER ENSEMBLE RTÉ CONCERT ORCHESTRA JOHN WILSON The Brendan G. Carroll Collection Erich Wolfgang Korngold, 1914, aged seventeen Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897 – 1957) Violin Concerto, Op. 35 (1937, revised 1945)* 24:48 in D major • in D-Dur • en ré majeur Dedicated to Alma Mahler-Werfel 1 I Moderato nobile – Poco più mosso – Meno – Meno mosso, cantabile – Più – Più – Tempo I – Poco meno – Tempo I – [Cadenza] – Pesante / Ritenuto – Poco più mosso – Tempo I – Meno, cantabile – Più – Più – Tempo I – Meno – Più mosso 9:00 2 II Romanze. Andante – Meno – Poco meno – Mosso – Poco meno (misterioso) – Avanti! – Tranquillo – Molto cantabile – Poco meno – Tranquillo (poco meno) – Più mosso – Adagio 8:29 3 III Finale. Allegro assai vivace – [ ] – Tempo I – [ ] – Tempo I – Poco meno (maestoso) – Fließend – Più tranquillo – Più mosso. Allegro – Più mosso – Poco meno 7:13 String Sextet, Op. 10 (1914 – 16)† 31:31 in D major • in D-Dur • en ré majeur Herrn Präsidenten Dr. Carl Ritter von Wiener gewidmet 3 4 I Tempo I. Moderato (mäßige ) – Tempo II (ruhig fließende – Festes Zeitmaß – Tempo III. Allegro – Tempo II – Etwas rascher (Tempo III) – Tempo II – Allmählich fließender – Tempo III – Wieder Tempo II – Tempo III – Drängend – Tempo I – Tempo III – Subito Tempo I (Doppelt so langsam) – Allmählich fließender werdend – Festes Zeitmaß – Tempo I – Tempo II (fließend) – Festes Zeitmaß – Tempo III – Ruhigere (Tempo II) – Etwas rascher (Tempo III) – Sehr breit – Tempo II – Subito Tempo III 9:50 5 II Adagio. Langsam – Etwas bewegter – Steigernd – Steigernd – Wieder nachlassend – Drängend – Steigernd – Sehr langsam – Noch ruhiger – Langsam steigernd – Etwas bewegter – Langsam – Sehr breit 8:27 6 III Intermezzo. -

Film Music Week 4 20Th Century Idioms - Jazz

Film Music Week 4 20th Century Idioms - Jazz alternative approaches to the romantic orchestra in 1950s (US & France) – with a special focus on jazz... 1950s It was not until the early 50’s that HW film scores solidly move into the 20th century (idiom). Alex North (influenced by : Bartok, Stravinsky) and Leonard Rosenman (influenced by: Schoenberg, and later, Ligeti) are important influences here. Also of note are Georges Antheil (The Plainsman, 1937) and David Raksin (Force of Evil, 1948). Prendergast suggests that in the 30’s & 40’s the films possessed somewhat operatic or unreal plots that didn’t lend themselves to dissonance or expressionistic ideas. As Hollywood moved towards more realistic portrayals, this music became more appropriate. Alex North, leader in a sparser style (as opposed to Korngold, Steiner, Newman) scored Death of a Salesman (image above)for Elia Kazan on Broadway – this led to North writing the Streetcar film score for Kazan. European influences Also Hollywood was beginning to be strongly influenced by European films which has much more adventuresome scores or (often) no scores at all. Fellini & Rota, Truffault & Georges Delerue, Maurice Jarre (Sundays & Cybele, 1962) and later the Professionals, 1966, Ennio Morricone (Serge Leone, jazz background). • Director Frederico Fellini &composer Nino Rota (many examples) • Director François Truffault & composerGeorges Delerue, • Composer Maurice Jarre (Sundays & Cybele, 1962) and later the • Professionals, 1966, Composer- Ennio Morricone (Serge Leone, jazz background). (continued) Also Hollywood was beginning to be strongly influenced by European films which has much more adventuresome scores or (often) no scores at all. Fellini & Rota, Truffault & Georges Delerue, Maurice Jarre (Sundays & Cybele, 1962) and later the Professionals, 1966, Ennio Morricone (Serge Leone, jazz background). -

Cinema Italiano Brochure

SOPRANO Diana DiMarzio “Diana DiMarzio ha una voce melodiosa” Oggi/Broadway & Dintorni by Mario Fratti Cinema Italiano salutes the many contributions Italian film composers have made to the film industry. This vocal concert treats music lovers to an evening of nostalgia, fun and romance as they listen to some of the screen sagas’ best remembered songs from composers such as Nino Rota, Ennio Morricone, Henry Mancini and more. These composers drew upon Italian musical traditions to add a sense of familial and cultural depth to these great Italian films. They tugged at our heartstrings and celebrated Italy’s unique sounds and spirit. This celebratory concert provides listeners, regardless of their background, with a deeper appreciation for the positive significant contributions made by Italians to our civilization, especially in the arts. Cinema Italiano / Program ACT I Cinema Italiano Maury Yeston, Nine Be Italian Maury Yeston, Nine Life is Beautiful/Buon Giorno Principessa Nicola Piovani, Life is Beautiful You’re Still You Ennio Morricone, Malena Don’t Take Your Love from Me Henry Nemo, (heard in) Big Night La Strada Nino Rota, La Strada Godfather Waltz/Parla Piu Piano Nino Rota, Godfather I Love Said Goodbye Nino Rota, Godfather II Donde Lieta (from La Boheme) Puccini, (heard in) Moonstruck Mambo Italiano/ Tic Ti, Tic Ta (heard in) Big Night ACT II Cinema Paradiso (Piano/instrumental solo) Ennio Morricone, Cinema Paradiso Spaghetti Western Medley Ennio Morricone, Good, Bad, and the Ugly/Fistful of Dynamite/Once Upon a Time in the West More Riz Ortolani, Le Mondo Cane Nella Fantasia Ennio Morricone, The Mission Cinema Paradiso Ennio Morricone, Cinema Paradiso It Had Better Be Tonight/Pink Panther Henry Mancini, Pink Panther (Dubbed in Italian) Mai Nino Oliviero, La Donna Nel Mondo Il Postino Luis Bacalov, Il Postino Con Te Partiro (Not yet heard in a movie) Diana DiMarzio dianadimarzio.com. -

30 Giugno 6 Luglio 2014

17* GENOVA 30 GIUGNO FILM 6 LUGLIO 2014 FESTIVAL 17* GENOVA 30 GIUGNO FILM 6 LUGLIO 2014 FESTIVAL DIREZIONE ARTISTICA E ORGANIZZATIVA Cristiano Palozzi Antonella Sica ASSISTENTE ALLA DIREZIONE Caterina Nascimbene SEGRETERIA ORGANIZZATIVA Associazione Culturale Daunbailò con la collaborazione di Thierry Bousseau RESPONSABILE TECNICO Raffaello Cantatore ASSISTENTI DI SALA Marika Cirillo Valeria Deplano Alessandra Gatti Ketlin Maffessoni Vanessa Sarti laia UFFICIO STAMPA Bonsai Film - Genova con la collaborazione di Davide Bressanin COMUNICAZIONE Bonsai Film – Genova collaborazione alla redazione del catalogo Alessandra Gatti FOTOGRAFO UFFICIALE Stefania Bianucci PROGETTO GRAFICO Matteo G. Palmieri SITO INTERNET Nunzio Gaeta (Cybear) Si ringrazia per la collaborazione tecnica: Luca Mattighello Fausto Chierchini Eugenia Oczoli Edvin Xifaj 2 - GENOVA FILM FESTIVAL 2014 Dedicato a Claudio G. Fava IL GENOVA FILM FESTIVAL RINGRAZIA (in ordine alfabetico) Angelo Berlangieri E inoltre: Nicola Borrelli Paolo Odone Carla Sibilla Daniele Biello Egidio Camponizzi Maurizio Caviglia Genovafilmservice Daniele D’Agostino Marina D’Andrea Genova Palazzo Ducale Anna Galleano Fondazione per la Cultura Elena Manara Sindacato Nazionale Critici Milena Palattella Cinematografici Italiani Carla Turinetto Claudio Bertieri Natalino Bruzzone Cecchi Gori HV Jacopo Chessa International Video 80 Oreste De Fornari Steve Della Casa Media One Entertainment Aldo De Scalzi Mira Films Gianluca De Serio Massimiliano De Serio Strani Film Maria Linda Germi Surf Film Martina Germi