Unit 2 Lakshmi Kannan and Indira Sant: Poems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DR. KOTI SANTOSH VIJAYKUMAR Qualification

Bio Data Full Name: DR. KOTI SANTOSH VIJAYKUMAR Qualification: M. A. (English), SET, NET, PGDTE, B. A. in MCJ, Prakrit Ratna, Ph. D. Designation: Principal, Walchand College of Arts and Science, Seth Walchand Hirachand Marg, Ashok Chowk, Solapur-413006 Department: English Date of Birth: 18/06/1977 Address: Flat No.9, Kuber Chambers, R – 1 Building, Vijapur Road, Solapur- 413 004 Mobile: 07588610930 E Mail Address: [email protected] Details of Educational Qualifications Degree Board/ Year of Grade % Subjects Remarks University Passing B. A. Shivaji University, 1997 I 61.44 English - Kolhapur M. A. Shivaji University, 1999 I 60.00 English (ELT) Gold Kolhapur Medalist SET University of Pune FEB. - - English - 2001 NET UGC, New Delhi DEC. - - English - 2001 PGDTE EFL University, FEB. B - English (ELT) - Hyderabad 2008 Ph. D. Shivaji University, 12 June - The Concept of - Kolhapur 2012 Nativism in Indian and African Literary Criticism B. A. in YCMOU, Nashik May I Dist. Mass 2012 Communic - - - ation and Journalism Prakrit Bahubali Prakrit May I Ratna Vidyapeeth, 2015 Srhavanbelgola - - 1 Appointment Details Sr. Name of the Nature of Date of Appointment No. Of No. College Appointment Years & Months From To 1 Lecturer Permanent 24/06/1999 31/12/2007 8 Years Krantiagrani G. D. 6 Months Bapu Lad College, Kundal; Dist: Sangli Associate Permanent 01/01/2008 27/03/2016 8Years 2 Professor, 3Months Walchand College of Arts and Science, Solapur 3 Principal, Tenure 28/03/2016 17/09/2018 2Years Hirachand (5 Years) 6Months Nemchand College of Commerce, Solapur 4 Principal, Tenure 18/09/2018 Till date 7 Months Walchand College (5 Years) of Arts and Science, Solapur Major Thrust Areas within the Subject: English Language Teaching (ELT) and Literary Criticism Total Teaching Experience 1. -

CIN/BCIN Company/Bank Name Investor First Investor Middle

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 CIN/BCIN L34102PN1958PLC011172 Prefill Company/Bank Name FORCE MOTORS LIMITED Date Of AGM( DD-MON-YYYY ) 11-Sep-2018 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 1350470.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) C/O M/S.RAJYALAKSHMI AGENCIES ALAGAPPACHETTIA 304 THAMBU CHETTY STREET FORC000000000A00 Amount for unclaimed and A L GOVINDAN R MADRAS INDIA Tamil Nadu 600001 0006 unpaid dividend 2000.00 12-Oct-2024 368 OLDFIELD LANE GREENFORD FORC000000000A00 Amount for unclaimed and ADARSH SETHI SOMDATTSETHI MIDDX UB6 8PX UK UNITED KINGDOM NA 999999 0021 unpaid dividend 4000.00 12-Oct-2024 FORC000000000A00 Amount for unclaimed and AJIT KUMAR PAL KALIPADAPAL 31 GARANHATTA STREET INDIA West Bengal 700006 0031 unpaid dividend 8000.00 12-Oct-2024 SHRILACHHMANDA FORC000000000A00 Amount for unclaimed and ANANT RAM SHARMA SS 5/63 PANJABI BAGH NEW DELHI INDIA Delhi 110026 0069 unpaid dividend 4000.00 12-Oct-2024 FORC000000000A00 Amount for unclaimed and ANUJ RAM GUPTA SHEODAYAL MUNGELI DIST. -

2.2 Lakshmi Kannan and Rasha Sundari Debi

BEGC-132 Selections From Indian Indira Gandhi National Open University School of Humanities Writing: Cultural Diversity Block 4 Womenspeak UNIT 1 A Woman’s Retelling of the Rama-Tale: The Chandrabati 5 Ramayana UNIT 2 Lakshmi Kannan and Indira Sant: Poems 17 UNIT 3 Naseem Shafaie: Poems 28 UNIT 4 ‘Sapavimochanam’ (‘The Redemption’) by 39 Pudhumaipithan EXPERTS COMMITTEE Dr. Anand Prakash Prof. Neera Singh Dr. Hema Raghavan Director (SOH). Dr. Vandita Gautam IGNOU FACULTY (ENGLISH) Dr. Chinganbam Anupama Prof. Malati Mathur Prof. Ameena Kazi Ansari Prof. Nandini Sahu Mr. Ramesh Menon Prof. Pramod Kumar Dr. Nupur Samuel Dr. Pema Eden Samdup Dr. Ruchi Kaushik Ms. Mridula Rashmi Kindo Dr. Malathy A. Dr. Ipshita Hajra Sasmal Dr. Cheryl R Jacob Dr. Chhaya Sawhney COURSE COORDINATOR Prof. Malati Mathur School of Humanities IGNOU, New Delhi BLOCK PREPARATON Course Writers Block Editor Dr. Vandita Gautam Prof. Malati Mathur School of Humanities, IGNOU Prof. Malati Mathur PRINT PRODUCTION Mr. K.N. Mohanan Mr. C.N. Pandey Assistant Registrar (Publication) Section Officer (Publication) MPDD, IGNOU, New Delhi MPDD, IGNOU, New Delhi November, 2019 Indira Gandhi National Open University, 2019 ISBN : All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form, by mimeograph or any other means, without permission in writing from the Indira Gandhi National Open University. Further information on Indira Gandhi National Open University courses may be obtained from the University's office at Maidan Garhi. New Delhi-110 068 or visit University’s web site http://www.ignou.ac.in Printed and published on behalf of the Indira Gandhi National Open University, New Delhi by Registrar, MPDD, IGNOU. -

CULTURE Karnataka’S Cultural Heritage Is Rich and Variegated

Chapter XIII CULTURE Karnataka’s cultural heritage is rich and variegated. Kannada literature saw its first work during 9th Century and in modern times it has created seven winners of Jnanapeetha Award for their literary talents. Literary activity in other languages of neighbouring areas in this state and purely local languages like Tulu and Kodava is also considerable. Journalism in Kannada has its history dating back to 1843 and has many achievements to its credit. Karnataka has thrown up outstanding personalities of historical significance. In the musical map of India, the State has bright spots, whether it is Hindustani or Karnatak, the latter having originated in this land. In the field of dance and art too Karnataka has creditable achievements. Yakshagana is both a folk and elite art is flourishing here. The State’s tradition in folk arts is also colourful.When one thinks of the cultural scene, Shivaram Karanth, Kuvempu, Dr. Rajkumar, Maya Rao, Mallikarjuna Mansur, T. Chaudiah, K.K.Hebbar, Panith Bheemasen Joshi, Gangubai Hangal, B.V. Karanth U.R. Anantha Murthy, Girish Karnad, Chandrashekar Kambar are a few bright faces that shine forth. An attempt is made to survey the cultural pageant of Karnataka in this chapter. LITERATURE Kannada Literature: Kannada literature has a history dating back to at least 1500 years. This apart, the folk literature which began earlier, still runs parallel to the written form Ganga king. Saigotta Sivarama’s ‘Gajashtaka’ is cited as an example of early folk literature. The oldest available work in Kannada is however, a book on poetics, called ‘Kavirajamarga’. Some controversy surrounds this work regarding the authorship, but the consensus is that it was written more likely by the court poet Srivijaya than the Rashtrakuta king Amoghavarsha Nripathunga. -

View Profile

Profile Department : Marathi Name of the Faculty : Dr. Pradnya Daya Pawar Designation : Associate Professor and Head of the Department Qualification/s : M.A., SET, Ph.D. Email ID : [email protected] Years of Experience : UG: 28 Years PG: 2 Years Thrust Area : Ism and literature, Social Movements and Literature. (Subject Interest) Details of Paper Presented : National Level: 1 National Level: Participated and presented paper on 'Marathi Adivasi Ani Dalit Kavita' in a seminar on 'Adhunik Marathi Kavita' in New Delhi organised by Sahitya Academy on 11th to 13th October 2012. Details of Publication : State Level: 33 State Level: Article entitled 'Manasachya Assalpanacha Shodh Ghete Mi' in book 'Stri-likhit Marathi Kavita (1950-2010)' (2016) Edited by Aruna Dhere, published by Padmagandha Prakashan, Pune ISBN 978-9384416-70-6 Article entitled 'Jat, Warga, Lingbhav Ani Dalit Sahityasamoril Awhane' in book 'Sandarbhasahit Strivad - Strivadache Samakalin Charchavishwa' (2014) Edited by Vandana Bhagwat and others, published by Shabda Publications, Mumbai ISBN 978-93-82364-13-1 Article entitled 'Virangi Mi!, Vimukta Mi' in monthly 'Mukta Shabda' ISSN 2347-3150 Article entitled 'Balatkar Virodhi Ladhyacha Wyapak Sandarbh' in 'Nirbhaya: Ek Atmachintan'(2013) an anthology edited by then V.C. of Mumbai University Dr.Rajan Velukar and published by Mumbai University. Article entitled 'Prashna Kharya Pratinidhitwacha' in 14th April 2018 issue of daily 'Maharashtra Times' https://maharashtratimes.indiatimes.com/editorial/article/- /articleshow/2949787.cms -

Download Shivneri

2019-20 {edZoar Aܶj àmMm¶© S>m°. EZ. Eg. Jm¶H$dmS> g§nmXH$ àm. g§Vmof nÙmH$a ndma g§nmXH ‘§S>i àm. JUoe dmK {dÚmWu à{V{ZYr àm. Ama. Eg. ZmB©H$ M¡Vݶ ¶odbo ({ÛÎmr¶ df©, H$bm) àm. h[a^OZ H$m§~io nyOm KmS>Jo (E‘. E., àW‘ df©, ‘amR>r) àVrjm {MIbo (V¥Vr¶ df©, H$bm ‘amR>r) g§nmXZ gmhmæ¶ àm. H¡$bmg Ea§S>o N>m¶m{MÌU ghH$m¶© àm. g§O¶ ndio àU¶ ‘hmOZ, AZwamYm ’$moQ>mo ñQw>{S>Amo, ‘§Ma g§O¶ Xidr, Ah‘XZJa {dVaU ì¶dñWm àm. g§O¶ ‘o‘mUo (J«§Wnmb) a¶V {ejU g§ñWoMo, AÊUmgmho~ AmdQ>o AmQ>©g², H$m°‘g© hþVmË‘m ~m~y JoZy gm¶Ýg H$m°boO Am{U gm¡.Hw$gw‘~oZ H$m§Vrbmb emh AmQ>©g², H$m°‘g©, gm¶Ýg Á¶w{Z¶a H$m°boO, ‘§Ma, Vm.Am§~oJmd, {O.nwUo, 410503 {edZoar & Shivneri ‘hm{dÚmb¶mMr d¡{eîQ>ço & CnH«$‘ {X àog A°³Q> A°ÊS> a{OñQ´>oeZ Am°’$ ~w³g {Z¶‘ 8, ’$m°‘© 4 à‘mUo Amdí¶H$ ‘m{hVr Z°H$Mr "A' J«oS> àmßV ‘hm{dÚmb¶, gm{dÌr~mB© ’w$bo nwUo {dÚmnrR>mMo ~oñQ> H$m°boO A°dm°S> {dOoVo ‘hm{dÚmb¶ àH$meZ ñWi 105 EH$amMm {ZgJ©aå¶ n[aga AÊUmgmho~ AmdQ>o ‘hm{dÚmb¶, ‘§Ma Vk, g§emoYH$, ì¶mg§Jr Am{U AZw^dr àmܶmnH$ d¥§X, {Z¶VH$m{bH$ : dm{f©H$ kmZ d¥Õr H$aUmao g‘¥Õ d àeñV J«§Wmb¶ Am{U ñdV§Ì Aä¶m{gH$m, A˶mYw{ZH$ g§JUH$, {dkmZ d ^mfm © ñdm{‘Ëd à¶moJemim, CVr g§dY©Z à¶moJemim ({Q>í¶w H$ëMa àmMm¶© S>m°. -

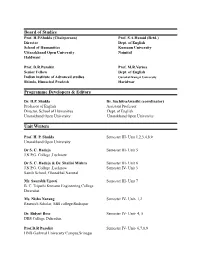

Mael 603,608 2020 Credit and Content Pages

Board of Studies Prof. H.P.Shukla (Chairperson) Prof. S.A.Hamid (Retd.) Director Dept. of English School of Humanities Kumaun University Uttarakhand Open University Nainital Haldwani Prof. D.R.Purohit Prof. M.R.Verma Senior Fellow Dept. of English Indian institute of Advanced studies Gurukul Kangri University Shimla, Himachal Pradesh Haridwar Programme Developers & Editors Dr. H.P. Shukla Dr. SuchitraAwasthi (coordinator) Professor of English Assistant Professor Director, School of Humanities Dept. of English Uttarakhand Open University Uttarakhand Open University Unit Writers Prof. H. P. Shukla Semester III- Unit 1,2,3,4,8,9 Uttarakhand Open University Dr S. C. Hadeja Semester III- Unit 5 J.N.P.G. College ,Lucknow Dr S. C. Hadeja & Dr. Shalini Mishra Semester III- Unit 6 J.N.P.G. College ,Lucknow Semester IV- Unit 3 Sainik School, Ghorakhal,Nainital Mr. Saurabh Upreti Semester III- Unit 7 B. C. Tripathi Kumaun Engineering College Dwarahat Ms. Nisha Narang Semester IV- Unit- 1,2 Research Scholar, SBS college,Rudrapur Dr. Bidyut Bose Semester IV- Unit- 4, 5 DBS College Dehradun Prof.D.R Purohit Semester IV- Unit- 6,7,8,9 HNB Garhwal University Campus,Srinagar Edition: 2020 ISBN : 978-93-84632-17-5 Copyright: Uttarakhand Open University, Haldwani Published by: Registrar, Uttarakhand Open University, Haldwani Email: [email protected] Printer: CONTENTS SEMESTER III BLOCK 1 Unit 1 Rigveda: Purusha Sukta 2-13 Unit 2 Isha Upanishad 14-29 Unit 3 The Mahabharata: The Yaksha Dialogue: Introducing the text 30-44 Unit 4 The Mahabharata: The Yaksha Dialogue: -

Arun Kolatkar and Bilingual Literary Culture

UC Irvine FlashPoints Title Bombay Modern: Arun Kolatkar and Bilingual Literary Culture Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2pk8z0z9 ISBN 978-0-8101-3273-3 Author Nerlekar, Anjali Publication Date 2016-04-21 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Bombay Modern The FlashPoints series is devoted to books that consider literature beyond strictly national and disciplinary frameworks, and that are distinguished both by their historical grounding and by their theoretical and conceptual strength. Our books engage theory without losing touch with history and work historically without falling into uncritical positivism. FlashPoints aims for a broad audience within the humanities and the social sciences concerned with moments of cultural emergence and transformation. In a Benjaminian mode, FlashPoints is interested in how literature contributes to forming new constellations of culture and history and in how such formations function critically and politically in the present. Series titles are available online at http://escholarship.org/uc/flashpoints. series editors: Ali Behdad (Comparative Literature and English, UCLA), Founding Editor; Judith Butler (Rhetoric and Comparative Literature, UC Berkeley), Founding Editor; Michelle Clayton (Hispanic Studies and Comparative Literature, Brown University); Edward Dimendberg (Film and Media Studies, Visual Studies, and European Languages and Studies, UC Irvine), Coordinator; Catherine Gallagher (English, UC Berkeley), Founding Editor; Nouri Gana (Comparative Literature and Near Eastern Languages and Cultures, UCLA); Susan Gillman (Literature, UC Santa Cruz); Jody Greene (Literature, UC Santa Cruz); Richard Terdiman (Literature, UC Santa Cruz) A complete list of titles begins on page 293. Bombay Modern Arun Kolatkar and Bilingual Literary Culture Anjali Nerlekar northwestern university press ❘ evanston, illinois this book is made possible by a collaborative grant from the andrew w.