Atenea Dec 2003.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE CONSTITUTIONAL IRRELEVANCE of ART, Brian Soucek

99 N.C. L. REV. 685 (2021) THE CONSTITUTIONAL IRRELEVANCE OF ART* BRIAN SOUCEK** In Masterpiece Cakeshop, the baker’s lead argument to the Supreme Court was that his cakes were artworks, so antidiscrimination laws could not apply. Across the country, vendors who refuse to provide services for same-sex weddings continue making similar arguments on behalf of their floral arrangements, videos, calligraphy, and graphic design, and the Supreme Court will again be asked to consider their claims. But arguments like these—what we might call “artistic exemption claims,” akin to the religious exemptions so much more widely discussed—are actually made throughout the law, not just in public accommodations cases like Masterpiece Cakeshop. In areas ranging from tax and tort, employment and contracting discrimination, to trademark, land use, and criminal law, litigants argue that otherwise generally applicable laws simply do not apply to artists or their artworks. This Article collects these artistic exemption claims together for the first time in order to examine what determines their occasional success—and to ask when and whether they should succeed. The surprising answer is that claims of the form “x is protected because it is art” should never succeed. The category “art” is constitutionally irrelevant. Contrary to widespread assertion among scholars and advocates, a work’s status as art has never done any work in the Supreme Court’s First Amendment case law. * © 2021 Brian Soucek. ** Professor of Law and Chancellor’s Fellow, University of California, Davis School of Law. To tackle a topic this broad is to rely on a wide circle of experts and friends. -

Photo-Activatable Oligonucleotides for Protein Modification and Surface Immobilization

Photo-Activatable Oligonucleotides for Protein Modification and Surface Immobilization Zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines DOKTORS DER NATURWISSENSCHAFTEN (Dr. rer. nat.) von der KIT-Fakultät für Chemie und Biowissenschaften des Karlsruher Instituts für Technologie (KIT) genehmigte DISSERTATION von Dipl.-Chem. Antonina Francevna Kerbs aus Almaty, Kasachstan KIT-Dekan: Prof. Dr. Willem Klopper Referent: Priv. Doz. Dr. Ljiljana Fruk Korreferent: Prof. Dr. Christopher Barner-Kowollik Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 21.10.2016 This document is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution – Share Alike 3.0 DE License (CC BY-SA 3.0 DE): http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/ Ich erkläre hiermit wahrheitsgemäß, dass die vorliegende Doktorarbeit im Rahmen der Betreuung durch Priv. Doz. Dr. Ljiljana Fruk selbständig verfasst und keine anderen als die angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmittel verwendet sowie alle wörtlich oder inhaltlich übernommenen Stellen als solche kenntlich gemacht wurden. Des Weiteren erkläre ich, dass ich mich derzeit in keinem laufenden Promotionsverfahren befinde, keine vorausgegangenen Promotionsversuche unternommen habe sowie die Satzung zur Sicherung guter wissenschaftlicher Praxis beachtet habe. Zusätzlich erkläre ich, dass die elektronische Version der Arbeit mit der schriftlichen übereinstimmt und dass die Primärdaten gemäß Abs. A (6) der Regeln zur Sicherung guter wissenschaftlicher Praxis des KIT beim Institut für Biologische Grenzflächen 1 zur Archivierung abgegeben wurden. Karlsruhe, den 03.11.2016 Antonina Kerbs Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde von Oktober 2012 bis Juni 2016 unter der Anleitung von Priv. Doz. Dr. Ljiljana Fruk am Karlsruher Institut für Technologie − Universitäts- und Großforschungsbereich angefertigt. Für meine Familie Abstract The ability to synthesize and modify short DNA sequences has helped to advance numerous research fields such as genomics, molecular biology, molecular engineering and nanobiotechnology. -

Casco Bay Weekly : 8 March 1990

Portland Public Library Portland Public Library Digital Commons Casco Bay Weekly (1990) Casco Bay Weekly 3-8-1990 Casco Bay Weekly : 8 March 1990 Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.portlandlibrary.com/cbw_1990 Recommended Citation "Casco Bay Weekly : 8 March 1990" (1990). Casco Bay Weekly (1990). 8. http://digitalcommons.portlandlibrary.com/cbw_1990/8 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Casco Bay Weekly at Portland Public Library Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Casco Bay Weekly (1990) by an authorized administrator of Portland Public Library Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Greater Portland's news and arts weekly FlEE - , l~I Benjamin Smith a .... lucy .......Iton w.1tz acNIS the d.nce floor during • lesson .t ~ .......room D.. e. CBWfTonee Harbert An invitation to the dance By Brenda Chandler With a little nudge you might be tempted mitzvah to escort a battle-ax aunt onto the to think you'd been beamed back to the floor. We think (oh, agony!) of being ap You open the door on a long wood-floored heyday of dance hall mania. And you'd not proached by a rum-sodden uncle at some room. The walls are pink. A stretch of mirrors be too far wrong. But this is now and this is humid wedding and of shuffling our feet to broadens the effect. The slow seductive Congress Street and the people you see glid the wheeze of an accordion. We think mostly sounds of ''Moon River" surround you. -

Arturo O'farrill Ron Horton Steve Potts Stan Getz

SEPTEMBER 2015—ISSUE 161 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM GARY BARTZ musical warrior ARTURO RON STEVE STAN O’FARRILL HORTON POTTS GETZ Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East SEPTEMBER 2015—ISSUE 161 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : Arturo O’Farrill 6 by russ musto [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : Ron Horton 7 by sean fitzell General Inquiries: [email protected] On The Cover : Gary Bartz 8 by james pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : Steve Potts by clifford Allen Editorial: 10 [email protected] Calendar: Lest We Forget : Stan Getz 10 by george kanzler [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel Spotlight : 482 Music by ken waxman [email protected] 11 Letters to the Editor: [email protected] VOXNEWS 11 by katie bull US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $35 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 In Memoriam 12 by andrey henkin For subscription assistance, send check, cash or money order to the address above or email [email protected] Festival Report 13 Staff Writers David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, CD Reviews 14 Fred Bouchard, Stuart Broomer, Katie Bull, Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Miscellany 39 Brad Farberman, Sean Fitzell, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Event Calendar Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, 40 Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Ken Waxman Alto saxophonist Gary Bartz (On The Cover) turns 75 this month and celebrates with two nights at Dizzy’s Club. -

Seeing Laure: Race and Modernity from Manet's Olympia to Matisse

Seeing Laure: Race and Modernity from Manet’s Olympia to Matisse, Bearden and Beyond Denise M. Murrell Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2013 Denise M. Murrell All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Seeing Laure: Race and Modernity from Manet’s Olympia to Matisse, Bearden and Beyond Denise M. Murrell During the 1860s in Paris, Edouard Manet and his circle transformed the style and content of art to reflect an emerging modernity in the social, political and economic life of the city. Manet’s Olympia (1863) was foundational to the new manner of painting that captured the changing realities of modern life in Paris. One readily observable development of the period was the emergence of a small but highly visible population of free blacks in the city, just fifteen years after the second and final French abolition of territorial slavery in 1848. The discourse around Olympia has centered almost exclusively on one of the two figures depicted: the eponymous prostitute whose portrayal constitutes a radical revision of conventional images of the courtesan. This dissertation will attempt to provide a sustained art-historical treatment of the second figure, the prostitute’s black maid, posed by a model whose name, as recorded by Manet, was Laure. It will first seek to establish that the maid figure of Olympia, in the context of precedent and Manet’s other images of Laure, can be seen as a focal point of interest, and as a representation of the complex racial dimension of modern life in post-abolition Paris. -

LESTER BOWIE Brass Memories

JUNE 2016—ISSUE 170 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM LESTER BOWIE brASS MEMories REZ MIKE BOBBY CHICO ABBASI REED PREVITE O’FARRILL Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East JUNE 2016—ISSUE 170 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : Rez Abbasi 6 by ken micallef [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : Mike Reed 7 by ken waxman General Inquiries: [email protected] On The Cover : Lester Bowie 8 by kurt gottschalk Advertising: [email protected] Encore : Bobby Previte by john pietaro Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : Chico O’Farrill 10 by ken dryden [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : El Negocito by ken waxman US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] In Memoriam by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Festival Report Stuart Broomer, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Philip Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD Reviews 14 Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Miscellany 41 Ken Micallef, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Event Calendar 42 Andrew Vélez, Ken Waxman Contributing Writers Tyran Grillo, George Kanzler, Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, Eric Wendell, Scott Yanow Jazz is a magical word. -

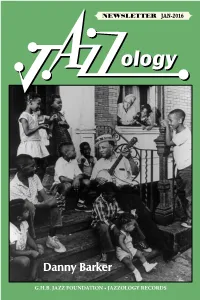

Danny Barker

NEWSLETTER JAN-2016 ologyology Danny Barker G.H.B. JAZZ FOUNDATION • JAZZOLOGY RECORDS DIGITAL RELEASES AVAILABLE EXCLUSIVELY THROUGH: BCD-538-DR BCD-540-DR JCD-402-DR JCD-403-DR PETE FOUNTAIN TOPSY CHAPMAN JIM CULLUM’S JIM CULLUM’S 1955-1957 The Best Of HAPPY JAZZ HAPPY JAZZ Listen Some More Happy Landing! PCD-7160-DR PCD-7162-DR PCD-7012-DR PCD-7021/23-DR BILL WATROUS BROOKS KERR - ROLAND HANNA SADIK HAKIM Watrous In PAUL QUINICHETTE Time For A Pearl For Errol / Hollywood Prevue The Dancers A Prayer For Liliane [2-LP Set] PCD-7164-DR PCD-7159-DR CCD-175-DR ACD-350-DR BUTCH MILES DANNY STILES FRANKIE CARLE REBECCA KILGORE Swings Some w BILL WATROUS Ivory Stride w Hal Smith’s Standards In Tandem 1946-1947 California Swing Cats Into the 80s ft. Tim Laughlin GEORGE H. BUCK JAZZ FOUNDATION 1206 DECATUR STREET • NEW ORLEANS, LA 70116 Phone: +1 (504) 525-5000 Office Manager: Lars Edegran Fax: +1 (504) 525-1776 Assistant: Jamie Wight Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Mon-Fri 11am – 5pm Website: www.jazzology.com Entrance: 61 French Market Place Newsletter Editor: Paige VanVorst Contributors: Lars Edegran, Ben Jaffe, Layout & Design: David Stocker David Stocker HOW TO ORDER COSTS – U.S. AND FOREIGN MEMBERSHIP If you wish to become a member of the Collector’s Record Club, please mail a check in the amount of $5.00 payable to the GHB JAZZ FOUNDATION. You will then receive your membership card by return mail or with your order. As a member of the Collector’s Club you will regularly receive our Jazzology Newsletter. -

Casco Bay Weekly (1989) Casco Bay Weekly

Portland Public Library Portland Public Library Digital Commons Casco Bay Weekly (1989) Casco Bay Weekly 12-14-1989 Casco Bay Weekly : 14 December 1989 Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.portlandlibrary.com/cbw_1989 Recommended Citation "Casco Bay Weekly : 14 December 1989" (1989). Casco Bay Weekly (1989). 50. http://digitalcommons.portlandlibrary.com/cbw_1989/50 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Casco Bay Weekly at Portland Public Library Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Casco Bay Weekly (1989) by an authorized administrator of Portland Public Library Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ~asc Greater Portland's news and arts weekly DECEMBER 14, 1989 FREE ~ ~- -:r-.... J Ul c!J j- ~ LU 0 Ul f' Each day during dlis holiday shopping season more dian 40,000 people parade across dlese tile noors. Each day dley spend more lIIan a milHon dollars. And each day lIIey return to a six-acre concrete beast so ubiquitous lIIat it has come to be known only as ... See page 6. + INSIDE: UPDATES page 2 LISTINGS page 14 IhleU. WEIRD NEWS page 3 ART page 19 Tolli~1(t tloL ~1I,:l is ~ ~,,~t.. O"r VIEWS page 4 POOK page 20 !.lUI, ku.rU . tb. trt.1'Ivt..). COVER page 6 CLASSIFIEDS page 21 STAGE page 11 PUZZLE page 23 Mc8attle brewing. Barroom theater. Barcelona sends her artists. CALENDAR page 12 Seepage 2 Seepage 11 See page 19 2 CASCO Bay Weekly Deumbtr 14,1989 3 A ,et/.ani.;} CYCLEMA N I Don't pay for useless (.)~:)~ packaging! TREK'SOO $279 TREK'S50 $409 TREK' 950 $569 A Great City Bike Suntour XCE equ'ipped American Technology Buy food in bulk. -

Mal Waldron Trio Mal 81 Mp3, Flac, Wma

Mal Waldron Trio Mal 81 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Mal 81 Country: Japan MP3 version RAR size: 1720 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1185 mb WMA version RAR size: 1556 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 764 Other Formats: VQF MPC DMF MP3 MIDI AU MOD Tracklist Hide Credits Love For Sale 1 6:40 Composed By – Cole Porter Summertime 2 6:20 Composed By – Heyward*, Gershwin* Angel Eyes 3 5:25 Composed By – E. K. Brent*, M. Dennis* Autumn Leaves 4 6:58 Composed By – Mercer*, Kosma* Body And Soul 5 6:52 Composed By – Heyman*, Eyton*, Green*, Sour* I Surrender Dear 6 7:13 Composed By – Clifford*, Barris* Yesterdays 7 4:16 Composed By – Kern*, Harbach* All Of You 8 5:29 Composed By – Cole Porter Companies, etc. Manufactured By – Teichiku Records Co., Ltd. Recorded At – RCA Recording Studios Credits Bass – George Mraz Drums – Al Foster Photography By – Veryl Oakland Piano – Mal Waldron Producer – Gus Statiras* Notes Recorded at RCA Recording Studios, New York, June 18, 1981 Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: T4988 004 002168 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Mal Waldron Mal 81 (LP, Progressive KUX-164-G KUX-164-G Japan 1981 Trio Album) Records Mal Waldron Mal 81 (LP, Progressive ULS-6077-G ULS-6077-G Japan 1981 Trio Album) Records Mal Waldron Mal 81 (CD, Progressive 35CP-6 35CP-6 Japan Unknown Trio Album, RE) Records Related Music albums to Mal 81 by Mal Waldron Trio Ralph Sharon Trio - The Magic Of Cole Porter James Melton - James Melton Sings George Gershwin / Cole Porter Sonia Spinello Quintet - Café Society Gershwin & Porter - Gold Collection Ella Fitzgerald & Cole Porter - Dream Dancing Cole Porter - Delightful, Delicious, De-lovely Joe Albany - The Legendary Pianist The Oscar Peterson Trio - In Tokyo, 1964 Cole Porter - Cole Porter - Great Orchestras Mal Waldron - And Alone Mabel Mercer - Mabel Mercer Sings Cole Porter Nat "King" Cole Trio - Classics. -

Elenco Codici Lp Completo 29 01 15

1 LADNIER TOMMY Play That Thing L/US.2.LAD 2 WOODS PHIL Great Art Of Jazz L/US.2.WOO 3 PARKER CHARLIE Volume 3 L/US.2.PAR 4 ZEITLIN DENNY Live At The Trident L/US.2.ZET 5 COLTRANE JOHN Tanganyika Strut L/US.2.COL 6 MCPHEE JOE Underground Railroad L/US.2.MCP 7 ELLIS DON Shock Treatment L/US.2.ELL 8 MCPHEE/SNYDER Pieces Of Light L/US.2.MCP 9 ROACH MAX The Many Sides Of... L/US.2.ROA 10 MCPHEE JOE Trinity L/US.2.MCP 11 ELLINGTON DUKE The Intimate Ellington L/US.2.ELL 12 V.S.O.P V.S.O.P. L/US.2.VSO 13 MILLER/COXHILL Coxhill/Miller L/EU.2.MIL 14 PARKER CHARLIE The "Bird" Return L/US.2.PAR 15 LEE JEANNE Conspiracy L/US.2.LEE 16 MANGELSDORFF ALBERT Birds Of Underground L/EU.2.MAN 17 STITT SONNY Stitt's Bits Vol.1 L/US.2.STI 18 ABRAMS MUHAL RICHARD Things To Come From Those Now Gone L/US.2.ABR 19 MAUPIN BENNIE The Jewel In The Lotus L/US.2.MAU 20 BRAXTON ANTHONY Live At Moers Festival L/US.2.BRA 21 THORNTON CLIFFORD Communications Network L/US.2.THO 22 COLE NAT KING The Best Of Nat King Cole L/US.2.COL 23 POWELL BUD Swngin' With Bud Vol. 2 L/US.2.POW 24 LITTLE BOOKER Series 2000 L/US.2.LIT 25 BRAXTON ANTHONY This Time... L/US.2.BRA 26 DAMERON TODD Memorial Album L/US.2.DAM 27 MINGUS CHARLES Live With Eric Dolphy L/US.2.MIN 28 AMBROSETTI FRANCO Dire Vol. -

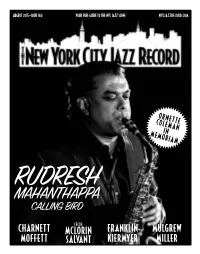

Rudresh Calling Bird

AUGUST 2015—ISSUE 160 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM ORNETTE COLEMAN MEMORIAMIN MAHANTHAPPARUDRESH CALLING BIRD CÉCILE CHARNETT MCLORIN FRANKLIN MULGREW MOFFETT SALVANT KIERMYER MILLER Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 116 Pinehurst Avenue, Ste. J41 AUGUST 2015—ISSUE 160 New York, NY 10033 United States New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: [email protected] Interview : Charnett Moffett by alex henderson Andrey Henkin: 6 [email protected] General Inquiries: Artist Feature : Cecile McLorin Salvant 7 by russ musto [email protected] Advertising: On The Cover : Rudresh Mahanthappa 8 by terrell holmes [email protected] Editorial: [email protected] Encore : Franklin Kiermyer 10 by james pietaro Calendar: [email protected] Lest We Forget : Mulgrew Miller 10 by ken dryden VOXNews: [email protected] Letters to the Editor: LAbel Spotlight : Xanadu 11 by donald elfman [email protected] VOXNEWS 11 by katie bull US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $35 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or money order to the address above In Memoriam 12 by andrey henkin or email [email protected] Festival Report Staff Writers 13 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Fred Bouchard, Stuart Broomer, In Memoriam : Ornette Coleman 14 Katie Bull, Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Brad Farberman, Sean Fitzell, -

Genre UPC Artist Title Street Date Sell Price Description DANCE 3596973242822 100 PERCENT SUMMER HITS 100 PERCENT SUMMER HITS 6

Genre UPC Artist Title Street Date Sell Price Description DANCE 3596973242822 100 PERCENT SUMMER HITS 100 PERCENT SUMMER HITS 6/16/2015 $30.75 5 CD ROCK 654436037323 ACID KING MIDDLE OF NOWHERE CENTER OF EVERYWHERE 6/16/2015 $17.75 ROCK 601091430952 ACTIVE CHILD MERCY 6/16/2015 $14.75 LATIN POP/ROCK 888750952721 AGUILAR,ANTONIO MIS NUMERO 1: MIS TESOROS 6/16/2015 $9.75 ROCK 825646235056 AIR VIRGIN SUICIDES: 15TH ANNIVERSARY 6/16/2015 $23.75 ROCK 851563006004 ALPINE YUCK 6/16/2015 $11.75 ROCK 5055664100196 AMORETTES GAME ON 6/16/2015 $23.75 DANCE 5060376221398 ANCIENT TECHNOLOGY ANCIENT TECHNOLOGY 6/16/2015 $25.75 ROCK 623339151528 APOLLO GHOSTS LANDMARK 6/16/2015 $17.75 ELECTRONIC 7393210252554 AZURE BLUE BENEATH THE HILL I SMELL THE SEA 6/16/2015 $23.75 ROCK 623339149228 BABY EAGLE BONE SOLDIERS 6/16/2015 $17.75 ROCK 888750969224 BABYMETAL BABYMETAL 6/16/2015 $12.75 ROCK 751097094327 BAD COP BAD COP NOT SORRY 6/16/2015 $17.75 JAZZ 819376066622 BALDWIN,BOB MELLOWONDER / SONGS IN THE KEY OF STEVIE 6/16/2015 $17.75 MUSICAL SOUNDTRACK 888295254328 BALDWIN,KATE / RYAN,CONOR JOHN & JEN (2015 OFF BROADWAY CAST RECORDING) 6/16/2015 $21.75 REGIONAL MEXICAN 602547300737 BANDA EL RECODO DE CRUZ LIZARRAGA MI VICIO MAS GRANDE 6/16/2015 $14.75 JAZZ 708857180929 BARRON,KENNY FLIGHT PATH 6/16/2015 $14.75 JAZZ 5070000037134 BEATS & PIECES BIG BAND ALL IN 6/16/2015 $30.75 ELECTRONIC 5414939922213 BECOMING REAL PURE APPARITION 6/16/2015 $17.75 JAZZ 888072371354 BENOIT,DAVID 2 IN LOVE 6/16/2015 $21.75 CLASSICAL ARTISTS 888750870025 BERGE VOR UNS DIE SINNFLUT