THE CONSTITUTIONAL IRRELEVANCE of ART, Brian Soucek

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Danielle Lloyd Forced to Defend 'Intense' Cosmetic Treatment | Daily Mail Online

Danielle Lloyd forced to defend 'intense' cosmetic treatment | Daily Mail Online Cookie Policy Feedback Like 3.9M Follow DailyMail Thursday, May 5th 2016 10AM 14°C 1PM 17°C 5-Day Forecast Home News U.S. Sport TV&Showbiz Australia Femail Health Science Money Video Travel Fashion Finder Latest Headlines TV&Showbiz U.S. Showbiz Headlines Arts Pictures Showbiz Boards Login 'It's not actually lipo': Danielle Lloyd forced Site Web to defend 'intense' cosmetic treatment after Like Follow Daily Mail Celeb @DailyMailCeleb bragging about getting her body summer- Follow ready Daily Mail Celeb By BECKY FREETH FOR MAILONLINE +1 Daily Mail Celeb PUBLISHED: 16:41, 20 January 2015 | UPDATED: 18:12, 20 January 2015 34 89 DON'T MISS shares View comments 'Ahh to be a Size 6 again': Gogglebox star Danielle Lloyd's Instagram followers voiced their concern on Tuesday, when the slender starlet posted Scarlett Moffatt shares a picture of her receiving what she said was intense 'lipo treatment'. a throwback of 'a very skinny minnie me' after Users who thought she was having the cosmetic procedure 'liposuction' - which removes body fat - vowing to overhaul her were quickly corrected by the glamour model in her defence. lifestyle The 31-year-old, who claimed she was 'getting ready for summer' in the initial Instagram snap, insisted it was a skin-tightening procedure known as a 'radio frequency treatment'. Chrissy Teigen reveals her incredible Scroll down for video post-baby body as she cuddles little Luna in sweet photos shared by her mother Relishing motherhood -

This Reunion of Past Glamourcover Faces— Assembled

0404-GL-WE01 What does strong and sexy look like these days? This reunion of past Glamour cover faces— TheGL assembled in honor of our 65th birthday— offers hints. NIKI TAYLOR, 29 CHRISTIE BRINKLEY, 50 EMMA HEMING, 25 CYBILL SHEPHERD, 54 LOUISE VYENT, 37 DANIELA PESTOVA, 33 The quintessential all-American look: a white top and and Spencer; jeans, Polo Jeans Co. Ralph Lauren. On jeans. On Cybill: Blouse, I.N.C.; jeans, Bella Elemento. On Daniela: Top, Grassroots; jeans, Blue Cult. On Molly: T-shirt, Niki: Tank, Left of Center; jeans, Nautica Jeans Company. Guess; jeans, Chip & Pepper; shoes, Manolo Blahnik. On On Louise: Shirt, Gap; jeans, Earl Jean. On Christie: Jacket, Patti: Tank, Mimi & Coco; jeans, Blue Cult; shoes, Salvatore Earl Jean; jeans, Levi’s. On Emma: Tank, Velvet by Graham Ferragamo. On Beverly: Top, Nike; jeans, Lucky Brand. Photographs by Pamela Hansen 0404-GL-WE02 AMOUR Girls BEVERLY JOHNSON, 51 MOLLY SIMS, 27 CHERYL TIEGS, 56 PATTI HANSEN, 47 PAULINA PORIZKOVA, 38 On Paulina: T-shirt, Gap; jeans, Earl Jean; shoes, Dolce & Hopson, Christiaan, Davy Newkirk for celestineagency.com, Gabbana. On Cheryl: T-shirt, La Cosa; jeans, Earl Jean; Brian Magallones, Eric Barnard. Makeup: Moyra Mulholland, shoes, Manolo Blahnik. All necklaces, Sparkling Sage. See Paige Smitherman for Marek & Associates, Monika Blunder for Go Shopping for more information. celestineagency.com, Eric Barnard. Manicures: Connie Kaufman Editors: Xanthipi Joannides, Maggie Mann. Hair: Maury for Louis Licari Salon, Lisa Postma for celestineagency.com. 215 0404-GL-WE03 THEIR cover MOMENTS Here’s how the super- models on the previous pages looked then, and how a few of them live now. -

Guide to the Cover Girl Advertising Oral History Documentation Project

Guide to the Cover Girl Advertising Oral History Documentation Project NMAH.AC.0374 Mimi L. Minnick The project was supported in part by a gift from the Noxell Corporation. 1990 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 4 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Research Files, 1925-1991; undated........................................................ 6 Series 2: Interviewee Files, 1990-1991.................................................................. 10 Series 3: Oral Histories, 1990-1991...................................................................... -

Photo-Activatable Oligonucleotides for Protein Modification and Surface Immobilization

Photo-Activatable Oligonucleotides for Protein Modification and Surface Immobilization Zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines DOKTORS DER NATURWISSENSCHAFTEN (Dr. rer. nat.) von der KIT-Fakultät für Chemie und Biowissenschaften des Karlsruher Instituts für Technologie (KIT) genehmigte DISSERTATION von Dipl.-Chem. Antonina Francevna Kerbs aus Almaty, Kasachstan KIT-Dekan: Prof. Dr. Willem Klopper Referent: Priv. Doz. Dr. Ljiljana Fruk Korreferent: Prof. Dr. Christopher Barner-Kowollik Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 21.10.2016 This document is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution – Share Alike 3.0 DE License (CC BY-SA 3.0 DE): http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/ Ich erkläre hiermit wahrheitsgemäß, dass die vorliegende Doktorarbeit im Rahmen der Betreuung durch Priv. Doz. Dr. Ljiljana Fruk selbständig verfasst und keine anderen als die angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmittel verwendet sowie alle wörtlich oder inhaltlich übernommenen Stellen als solche kenntlich gemacht wurden. Des Weiteren erkläre ich, dass ich mich derzeit in keinem laufenden Promotionsverfahren befinde, keine vorausgegangenen Promotionsversuche unternommen habe sowie die Satzung zur Sicherung guter wissenschaftlicher Praxis beachtet habe. Zusätzlich erkläre ich, dass die elektronische Version der Arbeit mit der schriftlichen übereinstimmt und dass die Primärdaten gemäß Abs. A (6) der Regeln zur Sicherung guter wissenschaftlicher Praxis des KIT beim Institut für Biologische Grenzflächen 1 zur Archivierung abgegeben wurden. Karlsruhe, den 03.11.2016 Antonina Kerbs Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde von Oktober 2012 bis Juni 2016 unter der Anleitung von Priv. Doz. Dr. Ljiljana Fruk am Karlsruher Institut für Technologie − Universitäts- und Großforschungsbereich angefertigt. Für meine Familie Abstract The ability to synthesize and modify short DNA sequences has helped to advance numerous research fields such as genomics, molecular biology, molecular engineering and nanobiotechnology. -

Casco Bay Weekly : 8 March 1990

Portland Public Library Portland Public Library Digital Commons Casco Bay Weekly (1990) Casco Bay Weekly 3-8-1990 Casco Bay Weekly : 8 March 1990 Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.portlandlibrary.com/cbw_1990 Recommended Citation "Casco Bay Weekly : 8 March 1990" (1990). Casco Bay Weekly (1990). 8. http://digitalcommons.portlandlibrary.com/cbw_1990/8 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Casco Bay Weekly at Portland Public Library Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Casco Bay Weekly (1990) by an authorized administrator of Portland Public Library Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Greater Portland's news and arts weekly FlEE - , l~I Benjamin Smith a .... lucy .......Iton w.1tz acNIS the d.nce floor during • lesson .t ~ .......room D.. e. CBWfTonee Harbert An invitation to the dance By Brenda Chandler With a little nudge you might be tempted mitzvah to escort a battle-ax aunt onto the to think you'd been beamed back to the floor. We think (oh, agony!) of being ap You open the door on a long wood-floored heyday of dance hall mania. And you'd not proached by a rum-sodden uncle at some room. The walls are pink. A stretch of mirrors be too far wrong. But this is now and this is humid wedding and of shuffling our feet to broadens the effect. The slow seductive Congress Street and the people you see glid the wheeze of an accordion. We think mostly sounds of ''Moon River" surround you. -

Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Magazine Pdf Free Download

Sports illustrated swimsuit magazine pdf free download Continue The most beautiful models in the world, hundreds of bikinis, and private tropical places, what can go wrong? More than you think, says make-up artist Tracy Murphy, who has been working on the Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Edition for 11 years. Something has always happened, says Murphy, who now carries everything from lip balm to Pepto-Bismol (we don't want to know). We talked to her about her must-have groceries on set and were surprised to learn that it's not always holiday-welcome news for the rest of us, mortals headed to the beach next weekend. They get tanned: Murphy slathers models in the highest SPF there, but it's still happening. If someone gets too red and has a sunburn, you should cover it with makeup, says Murphy. She loves the Koh Gen Do Maifanshi Moisture Foundation for its lined-up reach and compelling hues. They don't sleep in: Models arrive on set at 2 a.m., and Murphy covers them in Johnson's Baby Oil Gel. It's incredibly moisturizing and super-ish, she says. Then they sit in hair and makeup gowns and start shooting at dawn (when the light is beautiful). They sweat: Murphy holds the M.A.C. Prep and Prime Translucent Finishing Powder to control the oil around his lips and chin. It can go from sexy and wet to greasy and sloppy looking quickly, she says. They don't have perfect skin: Because of the frequent flyer models, they often come with dry skin and acne. -

Arturo O'farrill Ron Horton Steve Potts Stan Getz

SEPTEMBER 2015—ISSUE 161 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM GARY BARTZ musical warrior ARTURO RON STEVE STAN O’FARRILL HORTON POTTS GETZ Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East SEPTEMBER 2015—ISSUE 161 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : Arturo O’Farrill 6 by russ musto [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : Ron Horton 7 by sean fitzell General Inquiries: [email protected] On The Cover : Gary Bartz 8 by james pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : Steve Potts by clifford Allen Editorial: 10 [email protected] Calendar: Lest We Forget : Stan Getz 10 by george kanzler [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel Spotlight : 482 Music by ken waxman [email protected] 11 Letters to the Editor: [email protected] VOXNEWS 11 by katie bull US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $35 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 In Memoriam 12 by andrey henkin For subscription assistance, send check, cash or money order to the address above or email [email protected] Festival Report 13 Staff Writers David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, CD Reviews 14 Fred Bouchard, Stuart Broomer, Katie Bull, Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Miscellany 39 Brad Farberman, Sean Fitzell, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Event Calendar Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, 40 Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Ken Waxman Alto saxophonist Gary Bartz (On The Cover) turns 75 this month and celebrates with two nights at Dizzy’s Club. -

Seeing Laure: Race and Modernity from Manet's Olympia to Matisse

Seeing Laure: Race and Modernity from Manet’s Olympia to Matisse, Bearden and Beyond Denise M. Murrell Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2013 Denise M. Murrell All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Seeing Laure: Race and Modernity from Manet’s Olympia to Matisse, Bearden and Beyond Denise M. Murrell During the 1860s in Paris, Edouard Manet and his circle transformed the style and content of art to reflect an emerging modernity in the social, political and economic life of the city. Manet’s Olympia (1863) was foundational to the new manner of painting that captured the changing realities of modern life in Paris. One readily observable development of the period was the emergence of a small but highly visible population of free blacks in the city, just fifteen years after the second and final French abolition of territorial slavery in 1848. The discourse around Olympia has centered almost exclusively on one of the two figures depicted: the eponymous prostitute whose portrayal constitutes a radical revision of conventional images of the courtesan. This dissertation will attempt to provide a sustained art-historical treatment of the second figure, the prostitute’s black maid, posed by a model whose name, as recorded by Manet, was Laure. It will first seek to establish that the maid figure of Olympia, in the context of precedent and Manet’s other images of Laure, can be seen as a focal point of interest, and as a representation of the complex racial dimension of modern life in post-abolition Paris. -

083006 Tv Land Explores How Boomers Shook the World and Redefined the Rules in Network's Four-Part Series, Generation Boom

Contacts: Vanessa Reyes TV Land 310/752-8081 TV LAND EXPLORES HOW BOOMERS SHOOK THE WORLD AND REDEFINED THE RULES IN NETWORK’S FOUR-PART SERIES, GENERATION BOOM Special Examines How Boomers Play, Live, Love and Wire the World Beginning Tuesday, September 26 Narrated by Kelsey Grammer, Special Features Celebrity Interviews with Susan Sarandon, Rob Reiner, Christie Brinkley, Connie Chung, Penny Marshall, Cheryl Tiegs, Mark Cuban & More Santa Monica, CA, August 30, 2006 – From growing up in the suburbs to witnessing the original moon walk and from swirling a hula hoop to playing with hi-tech gadgets, baby boomers have shaped and continue to change the world we live in today. TV Land takes an entertaining and light-hearted look at what it means to be part of the grooviest generation in history when it presents Generation Boom , a four-part original special premiering on Tuesday, September 26 at 10 p.m. ET/PT . Narrated by Emmy Award-winning actor Kelsey Grammer (Frasier , Cheers ), each one-hour installment focuses on a central topic including how boomers play, live, love and wire the world. Airing over the course of four nights, Generation Boom is executive produced by Fenton Bailey and Randy Barbato and is produced exclusively for TV Land by World of Wonder. “Viewing the impact of Baby Boomers through the years is truly remarkable,” states Larry W. Jones, President, TV Land. “ Generation Boom shows just what a force this generation is to be reckoned with. Right away, boomers demanded more – beginning with the amount of diapers they needed. They have always insisted that the world conform to their needs and we are fully-prepared to get in line and do just that -- superserve the needs of the TV generation.” These one-hour specials -- airing over the course of four nights -- take an entertaining, fun and thorough look at the boomer generation. -

LESTER BOWIE Brass Memories

JUNE 2016—ISSUE 170 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM LESTER BOWIE brASS MEMories REZ MIKE BOBBY CHICO ABBASI REED PREVITE O’FARRILL Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East JUNE 2016—ISSUE 170 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : Rez Abbasi 6 by ken micallef [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : Mike Reed 7 by ken waxman General Inquiries: [email protected] On The Cover : Lester Bowie 8 by kurt gottschalk Advertising: [email protected] Encore : Bobby Previte by john pietaro Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : Chico O’Farrill 10 by ken dryden [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : El Negocito by ken waxman US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] In Memoriam by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Festival Report Stuart Broomer, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Philip Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD Reviews 14 Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Miscellany 41 Ken Micallef, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Event Calendar 42 Andrew Vélez, Ken Waxman Contributing Writers Tyran Grillo, George Kanzler, Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, Eric Wendell, Scott Yanow Jazz is a magical word. -

Lisa Jachno Manicurist

Lisa Jachno Manicurist Celebrities Adriana Lima Bella Thorn Elisha Cuthbert Helen Hunt Aisha Tyler Carmen Electra Elizabeth Banks Holly Hunter Alec Baldwin Carmen Kass Elizabeth Hurley Isabel Lucas Alessandra Ambrosio Carolyn Murphy Elizabeth Perkins Isabeli Fontana Alicia Silverstone Carrie-Anne Moss Elizabeth Shue J.C. Chavez Alicia Witt Carrie Underwood Elle MacPherson Jacqueline Smith Alyssa Milano Cate Blanchett Ellen Degeneres Jada Pinkett Amanda Seyfried Catherine Zeta Jones Ellen Barkin Jaime Pressly Amber Valletta Celine Dion Elle Fanning Jamie Lee Curtis America Ferrera Charlize Theron Emma Stone Jane Seymour Amy Adams Cher Emma Roberts Janet Jackson Anastasia Cheryl Tiegs Emmy Rossum January Jones Andie MacDowell Christina Aguilera Erika Christensen Jason Shaw Angelina Jolie Christina Applegate Estella Warren Jenna Fischer Angie Harmon Christina Ricci Eva Longoria Jeanne Tripplehorn Anjelica Huston Christy Turlington Evan Rachel Wood Jennifer Aniston Anna Kendrick Chole Moretz Faith Hill Jennifer Garner Anne Hathaway Ciara Farrah Fawcett Jennifer Lopez Annette Bening Cindy Crawford Fergie Jennifer Love Hewett Ashley Greene Claire Danes Fiona Apple Jennifer Hudson Ashley Judd Claudia Schiffer Fran Drescher Jennifer Tilly Ashley Tisdale Courteney Cox Gabrielle Union Jeremy Northam Ashlee Simpson Courtney Love Garcelle Beauvais Jeri Ryan Audrina Patridge Caroline Kennedy Gemma Ward Jessica Alba Avril Lavigne Daisy Fuentes Gerri Halliwell Jessica Biel Baby Face Daria Werbowy George Clooney Jessica Simpson Bette Midler Daryl Hannah -

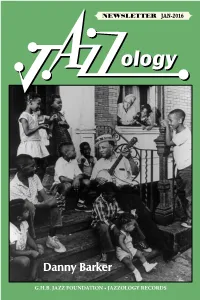

Danny Barker

NEWSLETTER JAN-2016 ologyology Danny Barker G.H.B. JAZZ FOUNDATION • JAZZOLOGY RECORDS DIGITAL RELEASES AVAILABLE EXCLUSIVELY THROUGH: BCD-538-DR BCD-540-DR JCD-402-DR JCD-403-DR PETE FOUNTAIN TOPSY CHAPMAN JIM CULLUM’S JIM CULLUM’S 1955-1957 The Best Of HAPPY JAZZ HAPPY JAZZ Listen Some More Happy Landing! PCD-7160-DR PCD-7162-DR PCD-7012-DR PCD-7021/23-DR BILL WATROUS BROOKS KERR - ROLAND HANNA SADIK HAKIM Watrous In PAUL QUINICHETTE Time For A Pearl For Errol / Hollywood Prevue The Dancers A Prayer For Liliane [2-LP Set] PCD-7164-DR PCD-7159-DR CCD-175-DR ACD-350-DR BUTCH MILES DANNY STILES FRANKIE CARLE REBECCA KILGORE Swings Some w BILL WATROUS Ivory Stride w Hal Smith’s Standards In Tandem 1946-1947 California Swing Cats Into the 80s ft. Tim Laughlin GEORGE H. BUCK JAZZ FOUNDATION 1206 DECATUR STREET • NEW ORLEANS, LA 70116 Phone: +1 (504) 525-5000 Office Manager: Lars Edegran Fax: +1 (504) 525-1776 Assistant: Jamie Wight Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Mon-Fri 11am – 5pm Website: www.jazzology.com Entrance: 61 French Market Place Newsletter Editor: Paige VanVorst Contributors: Lars Edegran, Ben Jaffe, Layout & Design: David Stocker David Stocker HOW TO ORDER COSTS – U.S. AND FOREIGN MEMBERSHIP If you wish to become a member of the Collector’s Record Club, please mail a check in the amount of $5.00 payable to the GHB JAZZ FOUNDATION. You will then receive your membership card by return mail or with your order. As a member of the Collector’s Club you will regularly receive our Jazzology Newsletter.