Kennedy and Nasser - a Failed Relationship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

King Faisal Assassinated

o.i> (Ejmttrrttrut iatlg (Sampita Serving Storrs Since 1896 VOL. LXXVIII NO. 102 STORRS, CONNECTICUT WEDNESDAY. MARCH 26. 1975 5 CENTS OFF CAMPUS King Faisal assassinated BEIRUT- (UPI) Saudi Khalid underwent heart surgery sacred cities of Mecca and monarch was wounded and Washington said the 31-year-old Arabi's King Faisal, spiritual in Cleveland, Ohio, three years Medina. hospitalized. Then. a .issassin was son of King Faisal's leader of the world's 600 million ago. t c a r - c h o k c d .innounccr half brother. Prince Musaid. The nephew walked the Moslems and master of the Faisal was killed while holding broadcast the news that Faisal Mideast's largest oil fields, was court in his Palace to mark the length of the hall apparently had died. Immediately all radio They said in 1966 he studied assassinated Tuesday as he sat on mniversary of the birth of intended to greet the seated King stations switched to readings of English at San Francisco State a golden chair in the mirrored Prophet Mohammed the with the customary kiss on both the Koran and thousands of College, and the following year hall of his palace by a deranged founder of the Islamic religion checks. Instead, he pulled a Saudis. (Tying and spreading he enrolled in a course in member of his own family. whose 600 million followers revolver from beneath his their arms in Uriel, surged into mechanical engineering at the Faisal, 68, died of wounds revered Faisal as their spiritual flowing robe and fired. the streets of Riyadh. -

Saudi Arabia Under King Faisal

SAUDI ARABIA UNDER KING FAISAL ABSTRACT || T^EsIs SubiviiTTEd FOR TIIE DEqREE of ' * ISLAMIC STUDIES ' ^ O^ilal Ahmad OZuttp UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF DR. ABDUL ALI READER DEPARTMENT OF ISLAMIC STUDIES ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1997 /•, •^iX ,:Q. ABSTRACT It is a well-known fact of history that ever since the assassination of capital Uthman in 656 A.D. the Political importance of Central Arabia, the cradle of Islam , including its two holiest cities Mecca and Medina, paled into in insignificance. The fourth Rashidi Calif 'Ali bin Abi Talib had already left Medina and made Kufa in Iraq his new capital not only because it was the main base of his power, but also because the weight of the far-flung expanding Islamic Empire had shifted its centre of gravity to the north. From that time onwards even Mecca and Medina came into the news only once annually on the occasion of the Haj. It was for similar reasons that the 'Umayyads 661-750 A.D. ruled form Damascus in Syria, while the Abbasids (750- 1258 A.D ) made Baghdad in Iraq their capital. However , after a long gap of inertia, Central Arabia again came into the limelight of the Muslim world with the rise of the Wahhabi movement launched jointly by the religious reformer Muhammad ibn Abd al Wahhab and his ally Muhammad bin saud, a chieftain of the town of Dar'iyah situated between *Uyayana and Riyadh in the fertile Wadi Hanifa. There can be no denying the fact that the early rulers of the Saudi family succeeded in bringing about political stability in strife-torn Central Arabia by fusing together the numerous war-like Bedouin tribes and the settled communities into a political entity under the banner of standard, Unitarian Islam as revived and preached by Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab. -

Us Military Assistance to Saudi Arabia, 1942-1964

DANCE OF SWORDS: U.S. MILITARY ASSISTANCE TO SAUDI ARABIA, 1942-1964 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Bruce R. Nardulli, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2002 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Allan R. Millett, Adviser Professor Peter L. Hahn _______________________ Adviser Professor David Stebenne History Graduate Program UMI Number: 3081949 ________________________________________________________ UMI Microform 3081949 Copyright 2003 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ____________________________________________________________ ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road PO Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 ABSTRACT The United States and Saudi Arabia have a long and complex history of security relations. These relations evolved under conditions in which both countries understood and valued the need for cooperation, but also were aware of its limits and the dangers of too close a partnership. U.S. security dealings with Saudi Arabia are an extreme, perhaps unique, case of how security ties unfolded under conditions in which sensitivities to those ties were always a central —oftentimes dominating—consideration. This was especially true in the most delicate area of military assistance. Distinct patterns of behavior by the two countries emerged as a result, patterns that continue to this day. This dissertation examines the first twenty years of the U.S.-Saudi military assistance relationship. It seeks to identify the principal factors responsible for how and why the military assistance process evolved as it did, focusing on the objectives and constraints of both U.S. -

The Hashemite Custodianship of Jerusalem's Islamic and Christian

THE HASHEMITE CUSTODIANSHIP OF JERUSALEM’S ISLAMIC AND CHRISTIAN HOLY SITES 1917–2020 CE White Paper The Royal Aal Al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought THE HASHEMITE CUSTODIANSHIP OF JERUSALEM’S ISLAMIC AND CHRISTIAN HOLY SITES 1917–2020 CE White Paper The Royal Aal Al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought THE HASHEMITE CUSTODIANSHIP OF JERUSALEM’S ISLAMIC AND CHRISTIAN HOLY SITES 1917–2020 CE Copyright © 2020 by The Royal Aal Al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought All rights reserved. No part of this document may be used or reproduced in any manner wthout the prior consent of the publisher. Cover Image: Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem © Shutterstock Title Page Image: Dome of the Rock and Jerusalem © Shutterstock isbn 978–9957–635–47–3 Printed in Jordan by The National Press Third print run CONTENTS ABSTRACT 5 INTRODUCTION: THE HASHEMITE CUSTODIANSHIP OF THE HOLY SITES IN JERUSALEM 7 PART ONE: THE ARAB, JEWISH, CHRISTIAN AND ISLAMIC HISTORY OF JERUSALEM IN BRIEF 9 PART TWO: THE CUSTODIANSHIP OF THE ISLAMIC HOLY SITES IN JERUSALEM 23 I. The Religious Significance of Jerusalem and its Holy Sites to Muslims 25 II. What is Meant by the ‘Islamic Holy Sites’ of Jerusalem? 30 III. The Significance of the Custodianship of Jerusalem’s Islamic Holy Sites 32 IV. The History of the Hashemite Custodianship of Jerusalem’s Islamic Holy Sites 33 V. The Functions of the Custodianship of Jerusalem’s Islamic Holy Sites 44 VI. Termination of the Islamic Custodianship 53 PART THREE: THE CUSTODIANSHIP OF THE CHRISTIAN HOLY SITES IN JERUSALEM 55 I. The Religious Significance of Jerusalem and its Holy Sites to Christians 57 II. -

Download Chapter (PDF)

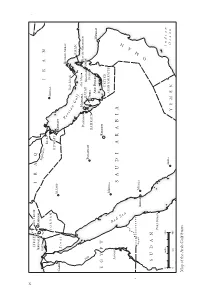

x ISRAEL WEST BANK IRAQ Jerusalem Amman Eup GAZA hrates IRAN Basra JORDAN Shiraz KUWAIT Al Jauf Kuwait Cairo Sinai P e Bandar Abbas r s i a Tunb Islands n G u OMAN l f Abu Musa Dammam Manama Ras Al-Khaimah N QATAR Ajman il Sharjah e Buraydah Dubai BAHRAIN Doha Abu Dhabi Muscat EGYPT Riyadh UNITED Medina ARAB EMIRATES R e Aswan d SAUDI ARABIA S e a N A Jeddah Mecca M O SUDAN Port Sudan 0 miles 250 Indian Abha Ocean 0 km 400 YEMEN Map of the Arab Gulf States 1. Muslim pilgrims circumambulate (tawaf ) the sacred Kaaba during sunrise after fajr prayer in Mecca, Saudi Arabia. 2. President Nixon and Mrs Nixon welcome King Faisal of Saudi Arabia on a visit to the United States in May 1971. 3. Henry Kissinger (left), the US Secretary of State, meets the Shah of Iran (right) in Zurich in early 1975. 4. Sheik Yamani talks about oil and the Palestinian problem during a press conference in Saudi Arabia in July 1979. 5. Crowds of Iranian protestors demonstrate in support of exiled Ayatollah Sayyid Ruhollah Khomeini in 1978, the year prior to the revolution. 6. Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein addresses members of his armed forces shortly before the invasion of Iran in September 1980. 7. Saudi Arabian soldiers prepare to load into armoured personnel carriers during clean-up operations following the Battle of Khafji, 2 February 1991. The Battle of Khafji was the first major ground engagement of the 1991 Gulf war. 8. Palestinian women demonstrate with Palestinian and Iraqi flags and portraits of Yasser Arafat and Saddam Hussein in the West Bank during the Kuwait crisis of 1990–91. -

The Arab-Israel War of 1967 1967 Was the Year of the Six-Day War

The Arab-Israel War of 1967 1967 was the year of the six-day war. Here we bring together its impact on Israel and on the Jewish communities in the Arab countries; United States Middle East policy and United Nations deliberations; effects on the East European Communist bloc, its citizens, and its Jewish communities, and American opinion. For discus- sions of reactions in other parts of the world, see the reviews of individual countries. THE EDITORS Middle East Israel A ALL aspects of Israel's life in 1967 were dominated by the explosion of hostilities on June 5. Two decades of Arab-Israel tension culminated in a massive combined Arab military threat, which was answered by a swift mobilization of Israel's citizen army and, after a period of waiting for international action, by a powerful offensive against the Egyptian, Jor- danian and Syrian forces, leading to the greatest victory in Jewish military annals. During the weeks of danger preceding the six-day war, Jewry throughout the world rallied to Israel's aid: immediate financial support was forthcoming on an unprecedented scale, and thousands of young volunteers offered per- sonal participation in Israel's defense, though they arrived too late to affect the issue (see reviews of individual countries). A new upsurge of national confidence swept away the morale crisis that had accompanied the economic slowdown in 1966. The worldwide Jewish reaction to Israel's danger, and the problems associated with the extension of its military rule over a million more Arabs, led to a reappraisal of atti- tudes towards diaspora Jewry. -

Rivalry in the Middle East: the History of Saudi-Iranian Relations and Its Implications on American Foreign Policy

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Summer 2017 Rivalry in the Middle East: The History of Saudi-Iranian Relations and its Implications on American Foreign Policy Derika Weddington Missouri State University, [email protected] As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the Defense and Security Studies Commons, International Relations Commons, and the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons Recommended Citation Weddington, Derika, "Rivalry in the Middle East: The History of Saudi-Iranian Relations and its Implications on American Foreign Policy" (2017). MSU Graduate Theses. 3129. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/3129 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RIVALRY IN THE MIDDLE EAST: THE HISTORY OF SAUDI-IRANIAN RELATIONS AND ITS IMPLICATIONS ON AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY A Masters Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University TEMPLATE In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science, Defense and Strategic Studies By Derika Weddington August 2017 RIVALARY IN THE MIDDLE EAST: THE HISTORY OF SAUDI-IRANIAN RELATIONS AND ITS IMPLICATIONS ON AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY Defense and Strategic Studies Missouri State University, August 2017 Master of Science Derika Weddington ABSTRACT The history of Saudi-Iranian relations has been fraught. -

The Six-Day War: Israel's Strategy and the Role of Air Power

The Six-Day War: Israel’s Strategy and the Role of Air Power Dr Michael Raska Research Fellow Military Transformations Program [email protected] Ponder the Improbable Outline: • Israel’s Traditional Security Concept 1948 – 1967 – 1973 • The Origins of the Conflict & Path to War International – Regional – Domestic Context • The War: June 5-10, 1967 • Conclusion: Strategic Implications and Enduring Legacy Ponder the Improbable Israel’s Traditional Security Concept 1948 – 1967 – 1973 תפישת הביטחון של ישראל Ponder the Improbable Baseline Assumptions: Security Conceptions Distinct set of generally shared organizing ideas concerning a given state’s national security problems, reflected in the thinking of the country’s political and military elite; Threat Operational Perceptions Experience Security Policy Defense Strategy Defense Management Military Doctrine Strategies & Tactics Political and military-oriented Force Structure Operational concepts and collection of means and ends Force Deployment fundamental principles by through which a state defines which military forces guide their and attempts to achieve its actions in support of objectives; national security; Ponder the Improbable Baseline Assumptions: Israel is engaged in a struggle for its very survival - Israel is in a perpetual state of “dormant war” even when no active hostilities exist; Given conditions of geostrategic inferiority, Israel cannot achieve complete strategic victory neither by unilaterally imposing peace or by military means alone; “Over the years it has become clear -

From Hussein to Abdullah: Jordan in Transition

THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE POLICY FOCUS FROM HUSSEIN TO ABDULLAH: JORDAN IN TRANSITION ROBERT SATLOFF RESEARCH MEMORANDUM Number Thirty-Eight April 1999 Cover and title page illustrations from the windows of the al-Hakim Bi-Amrillah Mosque, 990-1013 All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 1999 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy Published in 1999 in the United States of America by the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050, Washington, DC 20036 Contents Institute Staff Page iv About the Author v Acknowledgments vi Executive Summary vii From Hussein to Abdullah: Jordan in Transition 1 Appendix I: Correspondence between King Hussein and Prince Hassan 13 Appendix II: Correspondence between King Hussein and Prince Abdullah 19 Appendix III: Correspondence between King Abdullah and Prince Hassan 21 Appendix IV: Correspondence between King Abdullah and Prime Minister Abd al-Rauf al-Rawabdeh 23 Appendix V: Royal Decree Naming Hamzah Crown Prince 29 Appendix VI: Letter from King Abdullah to Queen Rania 30 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE for Near East Policy An educational foundation supporting scholarly research and informed debate on U.S. interests in the Near East President Executive Committee Chairman Michael Stein Barbi Weinberg Vice Presidents Charles Adler Robert Goldman Walter P. Stern Secretary/Treasurer Richard S. Abramson Fred Lafer Lawrence Phillips Richard Borow Martin J. -

Statement on the Death of King Hussein I of Jordan February 7, 1999

Administration of William J. Clinton, 1999 / Feb. 7 He once said, ‘‘The beauty of flying high in was the largest; the frailest was the strongest. the skies will always, to me, symbolize freedom.’’ The man with the least time remaining re- King Hussein lived his life on a higher plane, minded us we are working not only for ourselves with the aviator’s gift of seeing beyond the low- but for all eternity. flying obstacles of hatred and mistrust that To Queen Noor, I extend the heartfelt condo- heartbreak and loss place in all our paths. He lences of the American people. At times such spent his life fighting for the dignified aspira- as these, words are inadequate. But the friend- tions of his people and all Arab people. He ship that joins Jordan and the United States, worked all his life to build friendship between for which your marriage stood and your love the Jordanian and American people. He dedi- still stands, that will never fail. You are a daugh- cated the final years of his life to the promise ter of America and a Queen of Jordan. You not only of coexistence but of partnership be- have made two nations very proud. Hillary and tween the Arab world and Israel. I cherish the wonderful times we shared with Indeed, he understood what must be clear you and His Majesty. And today we say to you, now to anyone who has flown above the Middle and indeed to all the King’s large and loving East and seen in one panorama at sunset the family, our prayers are with you. -

Lumsden, George Quincy.Toc.Pdf

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR GEORGE QUINCEY LUMSDEN Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: January 11, 2000 Copyright 2006 A ST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born and raised in New Jersey Princeton University% Georgetown University US Navy Entered the Foreign Service in 1957 Educational Exchange Program Officer, New -ork .ity 1957-1959 State Department, FS0% German language studies 1959 01mir, Turkey% .onsular Officer 1959-1921 Environment 3arriage Government Bonn, Germany% Economic Officer 1922-1925 Export .ontrol President 6ennedy visit Junior .ircle of Bonn Diplomats Amman, Jordan% .hief of .onsular Section7Political Officer 1925-1927 Damascus anti-Assad demonstration 0mmigration visas US military assistance Environment Palestinians asser and Arab call for Arab Unity Arab-0srael 1927 war Riots Black September 6ing Hussein US Arab70srael Policy 1 Beirut, Lebanon, FS0% Arabic language studies 1927-1929 Environment Saudi students at American University of Beirut Ethnic and religious groups Palestinian refugees asser Arabic language program 6uwait% Economic Officer 1929-1972 Wealth Oil Production eutral 1one division Relations Education Environment Gulf Oil .ompany 0ran 0raq threat 6uwaitis Palestinians Egyptians British Border issues State Department% Desk Officer for 6uwait, Bahrain, Qatar 1972-1975 And United Arab Emirates Paris, France% Economic Officer 1975-1979 0nternational Petroleum Agency Oil .risis 0ranian Revolution France>s world role -

JCC Six Day War: Israel SILTMUN IV

JCC Six Day War: Israel SILTMUN IV Chair: Brian Forcier Political Officer: Sam Bugaieski Vice Chair: Kelly Roemer December 7nd, 2013 Lyons Township High School La Grange, Illinois Dear Delegates, My name is Brian Forcier, and I will be serving as your chair for SILMUN IV. My political officer is Sam Bugaieski, and my Vice Chair is Kelly Roemer. I am a junior at Saint Ignatius, while Sam and Kelly attend Lyons Township. I enjoy studying history, politics, and current events. I have been in Model U.N. since I was a freshman. My name is Sam Bugaieski, and I will be your PO in this year’s SILTMUN conference. I'm looking forward to seeing the interesting debate I'm sure you will all have when we start committee this December. I have been doing MUN for a little over a year now, and have taken part in a variety of conferences, both local and international. This is my first time participating as a leader in an event like this, and I can't wait to get a view of things from the perspective of the dais. I'm sure you will all do great when opening ceremonies end and the fun begins. I wish you all the best of luck in your research, and am excited to see the resolutions you come to early next year. The way we have arranged this cabinet is to provide the greatest depth into the topic. However, this obstacle proved to be difficult, accounting for the length of the war. I have decided to choose these topics as they provide the greatest depth, even though they shift in time.