Downloading Some Catalogue Records from Other

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spirit of Africa

FULL SCORE Spirit of Africa For Soprano Soloist, SATB Choir and Chamber Orchestra Photo: David Fanshawe, East Africa Music: Liz Lane Words: Jennifer Henderson Spirit of Africa Programme note Spirit of Africa is written as a companion piece to David Fanshawe’s African Sanctus and is inspired by the colours and symbolic meanings of the flags of Egypt, Sudan, Uganda and Kenya, the countries visited by David during his travels recording music for African Sanctus in 1969-1973. The words and music of the five movements trace a journey through the day, with the colour white for daybreak mist, green for morning freshness, red for midday heat, gold for sunset and black for night; each with its own mood and character, hopes and fears. Spirit of Africa is dedicated to David and his wife Jane. Liz Lane and Jennifer Henderson, May 2012 www.lizlane.co.uk 1. Promise of daybreak veiled in the early mist, hidden in shadows that cling to the night; Earth turning slowly toward a new journey into the morning, unknown, beyond sight. Birdsong dispelling the silence of waiting, lifting the darkness with wings taking flight; spray from the waterfall showering diamonds, carving the rock face with ribbons of white. Sweet is the air in the breath of the morning, spirit of purity, radiant light! 2. Dance, my friends, dance with the Earth, dance with the spring time of the year’s rebirth; dance with the sunshine, dance with the breeze, dance with the butterflies, dance with the bees. Sing, my friends, sing with the hills, sing with the river the rain cloud fills; sing with the green grass, sing with the trees, sing with the birds and the fish in the seas. -

AFRICAN SANCTUS Für Sopran, Chor, Instrumentalensemble Und Tonband Yvonne Friedli • Ölberg-Chor • Ingo Schulz Livemitschnitt Vom 19

David Fanshawe (*1942) AFRICAN SANCTUS für Sopran, Chor, Instrumentalensemble und Tonband Yvonne Friedli • Ölberg-Chor • Ingo Schulz www.emmaus.de Livemitschnitt vom 19. u. 20.5.2006, Emmaus-Kirche, Berlin-Kreuzberg „One World, one Music“ David Fanshawe (*1942): African Sanctus für Sopran, Chor, Instrumentalensemble und Tonband David Fanshawe ist Komponist, Forscher, Musikethnologe, Fotograf und Autor. Er hat zahlreiche internationale Auszeichnungen erhalten. Begonnen hat seine Karriere mit der Filmmontage, später dann wandte er sich am Royal College of Music mit John Lambert dem Studium der Komposition zu. 1970 fand er internationale Anerkennung mit Salaams, einem Werk, das auf Rhythmen der Perlenfischer von Bahrain aufbaut. Andere Konzertstücke: Fantasy on Dover Castle, Requiem for the Children of Aberfan, The Awakening, Dona Nobis Pacem. Neben Gesangsstücken hat er auch die Filmmusik für über 30 Filme und TV-Produktionen komponiert. Eine geglückte Mischung aus Musik und Reisen prägt seine sehr eigenen Werke. Seiner 10 Jahre dauernden Odyssee durch die Inseln des Pazifischen Ozeans verdanken wir unzählige Filme, Dias und handgeschriebene Hefte, die uns die Musik und mündlich überlieferten Traditionen Polynesiens, Mikronesiens und Melanesiens vermitteln. Heute lebt er in Wiltshire / Großbritannien................................ African Sanctus ist eine unorthodoxe Fassung der lateinischen Messe, in Einklang gebracht mit traditioneller afrikanischer Musik, die der Komponist auf seinen Nilreisen (1969-1973) aufgenommen hat. David Fanshawe reiste 1960 das erste Mal nach Afrika. Ihn bewegte die Idee, ein großes Werk zu komponieren, das seine Liebe zum Reisen, zum Abenteuer und zur Tonbanddokumentation vereinen sollte..................... In Kairo, auf dem Hügel der Zitadelle stehend und über den Nil blickend, hatte er zum ersten Mal die Vorstellung einer ungewöhnlichen Kombination von westlicher Chormusik mit dem Gebetsruf des islamischen Muezzin. -

2588Booklet.Pdf

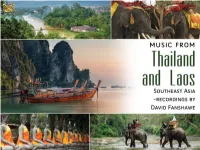

ENGLISH P. 2 DEUTSCH S. 8 MUSIC FROM THAILAND AND LAOS SOUTHEAST ASIA – RECORDINGS BY DAVID FANSHAWE DAVID FANSHAWE David Fanshawe was a composer, ethnic sound recordist, guest speaker, photographer, TV personality, and a Churchill Fellow. He was born in 1942 in Devon, England and was educated at St. George’s Choir School and Stowe, after which he joined a documentary film company. In 1965 he won a Foundation Scholarship to the Royal College of Music in London. His ambition to record indigenous folk music began in the Middle East in 1966, and was intensified on subsequent journeys through North and East Africa (1969 – 75) resulting in his unique and highly original blend of Music and Travel. His work has been the subject of BBC TV documentaries including: African Sanctus, Arabian Fantasy, Musical Mariner (National Geographic) and Tropical Beat. Compositions include his acclaimed choral work African Sanctus; also Dona nobis pacem – A Hymn for World Peace, Sea Images, Dover Castle, The Awakening, Serenata, Fanfare to Planet Earth / Millennium March. He has also scored many film and TV productions including Rank’s Tarka the Otter, BBC’s When the Boat Comes In and ITV’s Flambards. Since 1978, his ten years of research in the Pacific have resulted in a monumental archive, documenting the music and oral traditions of Polynesia, Micronesia and Melanesia. David has three children, Alexander and Rebecca with his first wife Judith; and Rachel with his second wife Jane. David was awarded an Honorary Degree of Doctor of Music from the University of the West of England (UWE) in 2009. -

Richard Dashwood

University of Huddersfield Repository Dashwood, Richard Composing With Anthropology: The Manifestation of Influence in Interactions between Western and Non-Western Music Original Citation Dashwood, Richard (2011) Composing With Anthropology: The Manifestation of Influence in Interactions between Western and Non-Western Music. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/12899/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ COMPOSING WITH ANTHROPOLOGY: THE MANIFESTATION OF INFLUENCE IN INTERACTIONS BETWEEN WESTERN AND NON-WESTERN MUSIC RICHARD DASHWOOD A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Art by Research The University of Huddersfield August 2011 Abstract The two aims of this thesis are the theoretical understanding, and the practical exploration, of the issues faced by Western art music composers when they engage with musical sources from Non-Western cultures. -

100 Piano Classics

100 Piano Classics: In The The Best Of The Red Army Lounge Choir Samuel Joseph Red Army Choir SILCD1427 | 738572142728 SILKD6034 | 738572603427 CD | Lounge Album | Russian Military Songs Samuel Joseph is 'The Pianists' Pianist'. Born in Hobart, Re-mastered from the original session tapes, the recordings Tasmania he grew up performing at restaurants, events and for this 2CD set were all made in Moscow over a number of competitions around the city before settling in London in years. They present the most complete and definitive 2005. He has brought his unique keyboard artistry to many collection of recordings of military and revolutionary songs celebrated London venues including the Dorchester, the by this most versatile of choirs. Includes Kalinka, My Savoy, Claridges, the Waldorf and Le Caprice. He has Country, Moscow Nights, The Cossacks, Song of the Volga entertained celebrities as diverse as Bono to Dustin Boatmen, Dark Eyes and the USSR National Anthem. Hoffman along with heads of state and royalty. Flair, vibrancy and impeccable presentation underline his keyboard skills. This 100 track collection highlights his astounding repertoire Swinging Mademoiselles - The Adventures Of Robinson Groovy French Sounds From Crusoe - Original TV The 60s Soundtrack Various Artists Robert Mellin & Gian-Piero SILCD1191 | 738572119126 Reverberi CD | French FILMCD705 | 5014929070520 CD | TV Soundtracks Long before England started swinging in the mid-1960s, One of the most evocative children's TV series of the 1960s France was the bastion for cool European pop sounds. is equally matched by Robert Mellin and Gian-Piero Sultry young French maidens, heavy on mascara and a Reverberi's enchanting score familiar to any young viewer of languid innocence cast a sexy spell with what became the period. -

Boys Will Be Boys Mt. Kili Madness

Old Stoic Society Committee President: Sir Richard Branson (Cobham/Lyttelton 68) Vice President: THE MAGAZINE FOR OLD STOICS Dr Anthony Wallersteiner (Headmaster) Chairman: Simon Shneerson (Temple 72) Issue 5 Vice Chairman: Jonathon Hall (Bruce 79) Director: Anna Semler (Nugent 05) Members: John Arkwright (Cobham 69) Peter Comber (Grenville 70) Jamie Douglas-Hamilton (Bruce 00) breaks Colin Dudgeon (Hon. Member) two world records. Hannah Durden (Nugent 01) John Fingleton (Chatham 66) Ivo Forde (Walpole 67) Tim Hart (Chandos 92) MT. KILI MADNESS Katie Lamb (Lyttelton 06) Cricket in the crater of Mount Kilimanjaro. Nigel Milne (Chandos 68) Jules Walker (Lyttelton 82) BOYS WILL BE BOYS ’Planes buzzing Stowe. Old Stoic Society Stowe School Stowe Buckingham MK18 5EH United Kingdom Telephone: +44 (0) 1280 818349 Email: [email protected] www.oldstoic.co.uk www.facebook.com/OldStoicSociety ISSN 2052-5494 Design and production: MCC Design, mccdesign.com AR END 2015 EVENTS CAL We have endeavoured to organise a wide range of events in 2015 that will appeal to Old Stoics of all ages. To make enquiries or to book any of the events below please call the Old Stoic Office on01280 818349 or email [email protected] Full details of each event can be found at www.oldstoic.co.uk To see more photos visit the OS Event Gallery at www.oldstoic.co.uk Tuesday, 17 March 2015 Monday, 6 July 2015 Old Stoics in Hong Kong Drinks Reception, Classic Car Track Day, £350 The Hong Kong Club, Hong Kong Goodwood, West Sussex, PO18 0PH Saturday, 21 March 2015 Sunday, 12 -

Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 2-27-2006 Concert: Ithaca College Madrigal Singers & Ithaca College Chorus Ithaca College Madrigal Singers Ithaca College Chorus Elizabeth K. Swanson Janet Galván Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Ithaca College Madrigal Singers; Ithaca College Chorus; Swanson, Elizabeth K.; and Galván, Janet, "Concert: Ithaca College Madrigal Singers & Ithaca College Chorus" (2006). All Concert & Recital Programs. 1614. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/1614 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. I T H A C **A C b LcL H G SCH'dObOF-· OSIC I I I· ITHACA COLLEGE MADRIGAL SINGERS Elizabeth K. Swanson, conductor ITHACA COLLEGE CHORUS Janet Galvan, conductor I I I Ford Hall _ I Monday, February 27, 2006 18:15 p.m. ITHACA COl,,LEGE MADRIGAL SINGERS Elizabeth K. Swanson, conductor Ave Maria Igor Stravinsky Ave Maria Tomas Luis de Victoria· Pater Noster Stra':'insky Five Hebrew Love Songs Eric Whitacre I. Temuna II. Kala kalla III. ·Larov IV. Eyze sheleg! V. Rakut Natasha Colkett, violin Allen Perriello, piano ,, ' Buy Baby Ribbon, (Tobagoan Lullaby) Steven Stucky from.Cradle Songs INTERMISSION ( ITHACA COLLEGE CHORUS Janet Galvan, conductor Mich.. ael, Lippert, graduate ·�onductor Reverence in many voices· Sanctus Leonard ,Ber_hstein From Mass A,lan Dust; Kay Seiner, Josef Hadar, percussionists Erev Shel Shoshanim arr. -

January 1997

Official Publication of the American Choral Directors Association US ISSN 0009-5028 JANUARY 1997 Official Publication of the American Choral Directors Association Volume Thirty-seven Number Six JANUARY 1997 CHORALjO John Silantien Barton L. Tyner Jr. EDITOR MANAGING EDITOR SPECIAL ISSUE nvenl:ion SAN DIEGO. CALIFORNIA MARCH 5 - 8 COLUMNS EVENTS From the Executive Director ....... 2 Schedule at a Glance .............................................. 9 From the President ...................... 3 From the Editor .......................... 4 Convention Schedule........................................... 11 Student Conducting International Choirs in Concert ........................... 25 Competition ............................. 90 National Convention ................ 93 Feature Concert ................................................... 33 Convention Program Index ....... 96 National Honor Choirs ........................................ 39 Advertisers Index....................... 96 Auditioned Choirs ................................................ 45 The covers showcase various San Diego sires, including the San Diego Convention Center and the San Diego Civic Theatre (Opera House). Pharos courresy of rhe San Diego Convention and Visitors Bureau. Concurrent Sessions ............................................. 67 JANUARY 1997 PAGE 1 FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR AFFILIATED ORGANIZATIONS ACDA Looks to the Past and the Future , INDIANA ,N HIS DECEMBER COLUMN, Lynn Whitten presented you with the wonder !(:::HORAL DIRECTORS ASSOCIATION ~ ful news -

Music Practices Across Borders

Glaucia Peres da Silva, Konstantin Hondros (eds.) Music Practices Across Borders Music and Sound Culture | Volume 35 Glaucia Peres da Silva (Dr.) works as assistant professor at the Institute of Sociology at the University of Duisburg-Essen. Her research focuses on global markets and music. Konstantin Hondros works as a research associate at the Institute of Sociology at the University of Duisburg-Essen. His research focuses on evaluation, mu- sic, and copyright. Glaucia Peres da Silva, Konstantin Hondros (eds.) Music Practices Across Borders (E)Valuating Space, Diversity and Exchange The electronic version of this book is freely available due to funding by OGeSo- Mo, a BMBF-project to support and analyse open access book publications in the humanities and social sciences (BMBF: Federal Ministry of Education and Research). The project is led by the University Library of Duisburg-Essen. For more information see https://www.uni-due.de/ogesomo. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Na- tionalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (BY) license, which means that the text may be remixed, transformed and built upon and be copied and redistributed in any medium or format even commercially, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Creative Commons license terms for re-use do not apply to any content (such as graphs, figures, photos, excerpts, etc.) not original to the Open Access publication and further permission may be required from the rights holder. -

1. Spirit of Africa

FULL SCORE Spirit of Africa For SATB Choir, Piano and Percussion (optional) Photo: David Fanshawe, East Africa Music: Liz Lane Words: Jennifer Henderson Spirit of Africa Programme note Spirit of Africa is written as a companion piece to David Fanshawe’s African Sanctus and is inspired by the colours and symbolic meanings of the flags of Egypt, Sudan, Uganda and Kenya, the countries visited by David during his travels recording music for African Sanctus in 1969-1973. The words and music of the five movements trace a journey through the day, with the colour white for daybreak mist, green for morning freshness, red for midday heat, gold for sunset and black for night; each with its own mood and character, hopes and fears. Spirit of Africa is dedicated to David and his wife Jane. Liz Lane and Jennifer Henderson, May 2012 www.lizlane.co.uk 1. Promise of daybreak veiled in the early mist, hidden in shadows that cling to the night; Earth turning slowly toward a new journey into the morning, unknown, beyond sight. Birdsong dispelling the silence of waiting, lifting the darkness with wings taking flight; spray from the waterfall showering diamonds, carving the rock face with ribbons of white. Sweet is the air in the breath of the morning, spirit of purity, radiant light! 2. Dance, my friends, dance with the Earth, dance with the spring time of the year’s rebirth; dance with the sunshine, dance with the breeze, dance with the butterflies, dance with the bees. Sing, my friends, sing with the hills, sing with the river the rain cloud fills; sing with the green grass, sing with the trees, sing with the birds and the fish in the seas. -

MAKING the GRADE an Insight Into Michael Grade, One of the Most Influential Figures in British Television

Old Stoic Society Committee Chris Atkinson (Chatham 59) Dr Anthony Wallersteiner (Headmaster) Ivo Forde (Walpole 67) Simon Shneerson (Temple 72) THE MAGAZINE FOR OLD STOICS John Arkwright (Cobham 69) Elizabeth Browne (Stanhope 81) Patrick Cooper (Chatham 86) Issue 1 Colin Dudgeon (Associate Member) Hannah Durden (Nugent 01) Peter Farquhar (Associate Member) John Fingleton (Chatham 66) Ed Gambarini (Cobham 00) Tim Hart (Chandos 92) Hannah James (Nugent 97) Nigel Milne (Chandos 68) Tim Scarff (Grenville 91) Ben Scholfield (Temple 99) MAKING THE GRADE An insight into Michael Grade, one of the most influential figures in British television. Old Stoic Society Stowe School Stowe THERE GO THE GIRLS Buckingham MK18 5EH Hannah Durden (Nugent 01) looks into United Kingdom the lives of some of the OS Girls. Telephone: +44 (0) 1280 818349 e-mail: [email protected] THE NEW INN www.oldstoic.org John Garratt (Cobham 53) reveals how the National Trust intend to restore the New Inn to recreate the original approach and access for visitors to Stowe. r A nd E l A 2011 EvEnTS C We have endeavoured to organise a wide range of events in 2011 that will appeal to Old Stoics of all ages. To make enquiries or to book any of the events below please call the Old Stoic Office on 01280 818349 or E-mail [email protected] 1 March 2011 28 May 2011 18/19 June 2011 21 September 2011 Old Stoics and Stowe Parents in Speech Day and the Old Stoic David Shepherd Wildlife 50th Anniversary reunion lunch the City Networking reception Classic Car Meeting Foundation Art Exhibition Stowe Green’s Restaurant, Stowe Stowe London EC3V 3ND For those who left Stowe in 1960 or 1961. -

"Exoticism Globalised: the Forgotten Roots of World Music"

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Chichester EPrints Repository Exoticism Globalised in a New Century: The Forgotten Roots of World Music by Dr. Jonathan Little, B.Mus.(Hons.), Th.A., Ph.D. Principal, Academy of Contemporary Music (Guildford, U.K.) Managing Editor, Music Business Journal Consultant Editor, Musicians’ and Songwriters’ Yearbook Since the 1840's, the so-called "Third World" has played a significant and often understated role in the development of the global music industry, but its impact has been more that of a cultural and spiritual donor than as a commercial exporter deriving benefit from products originating from strongly developing economies. It has often been cogently argued – by historians such as Lord Briggs – that all the great cultural movements, as well as the most remarkable technological innovations, of the twentieth century (and indeed beyond), have their roots firmly planted in the nineteenth century. This contention would seem to be borne out by the relatively recent phenomenon of "World Music". To prove such an argument in this particular musical context, we must initially, therefore, look back to the beginning of the "modern period": to an age when railways and steamships were starting to open up the world to trade, mass travel and tourism, for the first time. More precisely, a time-traveller of today might be struck by the novel sounds that were catching the public's imagination in 1844. If you were sitting in a Paris concert hall in that year, you might well have heard a completely new and "foreign" kind of music of a type that soon became immensely popular, and made its composer famous literally overnight.