Crossover: Boundaries, Hybridity, and the Problem of Opposing Cultures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Effect of Birthday on the Fluctuation of Suicides in Hungary

REVIEW OF SOCIOLOGY 20(2): 96–105. The Effect of Birthday on the Fluctuation of Suicides STUDIES in Hungary (1970–2002) Tamás ZONDA – Károly BOZSONYI – Előd VERES – Zoltán KMEttY email: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT: The authors have not found any studies that show an unambiguous and close relation between the date of suicide and the birthday of the victims. They made an analysis on the Hungarian suicides between 1970 and 2002 with a method known from the literature and also with a modern, more sophisticated one. It was found that Hungarian men show explicit sensitivity to their birthday’s date: significantly more men commit suicide on their birthday in all age groups than on any other day of the year. Among women, a relation of weak significance appeared only in the older age group. The authors suggest the special sensitivity of Hungarian men which they interpret in the framework of Gabennesch’s ”broken promise effect”, but they think it necessary to do further research on this theme in Hungary. Introduction Researches in the past decades have revealed several circumstances in the back- ground of a particular suicide that are generally typical and almost identical in every fatal action, but many circumstances and relationships that are inter- pretable or understandable with difficulty are discovered during the precise reconstruction of a tragic action. The decision of self-destruction is composed of a complicated mesh of numerous life events, injuries and constellations of personality development. It is known that certain biographical dates affect the personality to a greater or lesser extent. -

FCC-06-11A1.Pdf

Federal Communications Commission FCC 06-11 Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Annual Assessment of the Status of Competition ) MB Docket No. 05-255 in the Market for the Delivery of Video ) Programming ) TWELFTH ANNUAL REPORT Adopted: February 10, 2006 Released: March 3, 2006 Comment Date: April 3, 2006 Reply Comment Date: April 18, 2006 By the Commission: Chairman Martin, Commissioners Copps, Adelstein, and Tate issuing separate statements. TABLE OF CONTENTS Heading Paragraph # I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................. 1 A. Scope of this Report......................................................................................................................... 2 B. Summary.......................................................................................................................................... 4 1. The Current State of Competition: 2005 ................................................................................... 4 2. General Findings ....................................................................................................................... 6 3. Specific Findings....................................................................................................................... 8 II. COMPETITORS IN THE MARKET FOR THE DELIVERY OF VIDEO PROGRAMMING ......... 27 A. Cable Television Service .............................................................................................................. -

The Parish Magazine for the Presteigne Group of Parishes Has Continued to Appear – Either Online Or in Print

Your Parish Magazine Throughout the Covid-19 pandemic crisis, the Parish Magazine for the Presteigne Group of Parishes has continued to appear – either online or in print. The parish magazine Deadline dates for Copy and Artwork For as at 28th April 2021 Presteigne With th Wednesday 19 May June issue Discoed, Kinsham, Lingen and Knill rd Wednesday 23 June July/August issue Wednesday 18th August September issue Here Is your socially-distanced but Colourful We are particularly grateful to the Town Council, our friends in Lingen, our gardener, our new weather reporter and our occasional nature-noter. We include requests for support from community groups and charities. We hope to inform and Online MERRY MONTH OF may 2021 Issue, Fa La perhaps entertain you. The Editor welcomes announcements (remember them?) and appreciates contributions from anyone and everyone from our churches and parishes, groups, schools etc. Artwork (logos, etc) should be not too complicated (one day we will be printing again in black only on a photocopier so please keep designs simple). Articles as well as artwork must be set to fit an A5 page with narrow margins. The editor reserves the right to select and edit down items for which there is insufficient space. While you may be reading this issue on screen, you can print the whole issue, or selected pages, on A4 paper in landscape to both sides (Duplex). We suggest you select ‘short-side stapling’. Note: The ‘inside’ pages have been consecutively numbered on each sheet - unlike the pages which normally make up a magazine. You are encouraged to forward this magazine to others by email or as hard copy, as above – on condition that it is neither added to, nor the text altered, in any way. -

Looking Back Featured Stories from the Past

ISSN-1079-7832 A Publication of the Immortalist Society Longevity Through Technology Volume 49 - Number 01 Looking Back Featured stories from the past www.immortalistsociety.org www.cryonics.org www.americancryonics.org Who will be there for YOU? Don’t wait to make your plans. Your life may depend on it. Suspended Animation fields teams of specially trained cardio-thoracic surgeons, cardiac perfusionists and other medical professionals with state-of-the-art equipment to provide stabilization care for Cryonics Institute members in the continental U.S. Cryonics Institute members can contract with Suspended Animation for comprehensive standby, stabilization and transport services using life insurance or other payment options. Speak to a nurse today about how to sign up. Call 1-949-482-2150 or email [email protected] MKMCAD160206 216 605.83A SuspendAnim_Ad_1115.indd 1 11/12/15 4:42 PM Why should You join the Cryonics Institute? The Cryonics Institute is the world’s leading non-profit cryonics organization bringing state of the art cryonic suspensions to the public at the most affordable price. CI was founded by the “father of cryonics,” Robert C.W. Ettinger in 1976 as a means to preserve life at liquid nitrogen temperatures. It is hoped that as the future unveils newer and more sophisticated medical nanotechnology, people preserved by CI may be restored to youth and health. 1) Cryonic Preservation 7) Funding Programs Membership qualifies you to arrange and fund a vitrification Cryopreservation with CI can be funded through approved (anti-crystallization) perfusion and cooling upon legal death, life insurance policies issued in the USA or other countries. -

End of Year Charts: 2010

End Of Year Charts: 2010 Chart Page(s) Top 200 Singles .. .. .. .. .. 2 - 5 Top 200 Albums .. .. .. .. .. 6 - 9 Top 200 Compilation Albums .. .. .. 10 - 13 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, posted on an Internet/Intranet web site or forum, forwarded by email, or otherwise transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording without prior written permission of UKChartsPlus Published by: UKChartsPlus e-mail: [email protected] http://www.UKChartsPlus.co.uk - 1 - Symbols: Platinum (600,000) Gold (400,000) Silver (200,000) 12” Vinyl only 2010 7” Vinyl only Download only Entry Date 2010 2009 2008 2007 Title - Artist Label (Cat. No.) (w/e) High Wks 1 -- -- -- LOVE THE WAY YOU LIE - Eminem featuring Rihanna Interscope (2748233) 03/07/2010 2 28 2 -- -- -- WHEN WE COLLIDE - Matt Cardle Syco (88697837092) 25/12/2010 13 3 3 -- -- -- JUST THE WAY YOU ARE (AMAZING) - Bruno Mars Elektra ( USAT21001269) 02/10/2010 12 15 4 -- -- -- ONLY GIRL (IN THE WORLD) - Rihanna Def Jam (2755511) 06/11/2010 12 10 5 -- -- -- OMG - Usher featuring will.i.am LaFace ( USLF20900103) 03/04/2010 1 41 6 -- -- -- FIREFLIES - Owl City Island ( USUM70916628) 16/01/2010 13 51 7 -- -- -- AIRPLANES - B.o.B featuring Hayley Williams Atlantic (AT0353CD) 12/06/2010 1 31 8 -- -- -- CALIFORNIA GURLS - Katy Perry featuring Snoop Dogg Virgin (VSCDT2013) 03/07/2010 12 28 WE NO SPEAK AMERICANO - Yolanda Be Cool vs D Cup 9 -- -- -- 17/07/2010 1 26 All Around The World/Universal -

Les Sirènes Female Chamber Choir There Is No Rose

Les Sirènes Female Chamber Choir There is No Rose NI6249 Les Sirènes Royal Conservatoire of Scotland At the Royal Conservatoire we are creating the Female Chamber Choir future for performance. There is No Rose We provide vocational education at the highest professional level in dance, drama, music, production, and screen. We offer an extraordinary blend of intensive BENJAMIN BRITTEN (1913-1976) TARIK O’REGAN (b.1978) tuition, world-class facilities, a full performance A Ceremony of Carols, Op.28 (23:25) 16. Bring Rest, Sweet Dreaming Child (4:25) schedule, the space to collaborate across the disciplines, 1. Procession (1:51) teaching from renowned staff and industry practitioners, 2. Wolcum Yole! (1:21) TRADITIONAL arranged LIONEL SALTER (1914-2000) and unrivalled professional partnerships. 3. There is no rose (2:44) 17. The Coventry Carol (2:44) 4. That yongë child (1:43) World premiere recording We have over 900 students from around the world 5. Balulalow (1:28) studying on our specialist undergraduate and postgraduate degree programmes. Alongside, we offer 6. As dew in Aprille (1:01) GUSTAV HOLST (1874-1934) evening and weekend classes, short courses, summer 7. This little babe (1:30) 18. Jesu, thou the Virgin-born (2:56) schools, and a programme of continuing professional 8. Interlude (3:46) development. Our Junior Conservatoire for 7-18 year 9. In freezing winter night (3:38) SIR PHILIP LEDGER (1937-2012) olds nurtures young musical talent and we also organise 10. Spring carol (1:14) 19. Matthew, Mark, Luke and John (2:46) the Royal Conservatoire Music Centres programme, 11. -

01 to 06 MAY Terry Waite

Mark Billingham Ross Collins Kerry Brown Maura Dooley Matt Haig Darren Henley Emma Healey Patrick Gale Guernsey Literary Erin Kelly Huw Lewis-Jones Adam Kay Kiran Millwood Hargrave Kiran FestivalLibby Purves 2019 Lionel Shriver Philip Norman Philip 01 TO 06 MAY Terry Waite Terry Chrissie Wellington Piers Torday Lucy Siegle Lemn Sissay MBE Jessica Hepworth Benjamin Zephaniah ANA LEAF FOUNDATION MOONPIG APPLEBY OSA RECRUITMENT BROWNS ADVOCATES PRAXISIFM BUTTERFIELD RANDALLS DOREY FINANCIAL MODELLING RAWLINSON & HUNTER GUERNSEY ARTS COMMISSION ROTHSCHILD & CO GUERNSEY POST SPECSAVERS JULIUS BAER THE FORT GROUP Sophy Henn Kindly sponsored by sponsored Kindly THE INTERNATIONAL STOCK EXCHANGE THE GUERNSEY SOCIETY Turning the Tide on Plastic: How St James: £10/£5 Lucy Siegle Humanity (And You) Can Make Our Welcome to the Globe Clean Again seventh Guernsey Presenter on BBC’s The One Show and columnist for the Observer and the Guardian, Lucy Siegle offers a unique and beguiling perspective on environmental issues and ethical consumerism. Turning the Tide on Literary Festival Plastic provides a powerful call to arms to end the plastic pandemic along with the tools we need to make decisive change. It is a clear- eyed, authoritative and accessible guide to help us to take decisive and 13:00 to 14:00 effective personal action. Thursday 2 May Message from Sponsored by PraxisIFM Message from Claire Allen, Terry Waite CBE OGH Hotel: £25 Festival Director This is Going to Hurt Business Breakfast As Honorary I am very proud to welcome Professor Kerry you to the seventh Guernsey Chairman of the Literary Festival! With over Adam Kay Thursday 2 May Brown: The World Guernsey Literary 19:30 to 20:30 60 events for all interests According to Xi Festival it is once and ages, the festival is a Kerry Brown is Professor of again my pleasure unique opportunity to be inspired by writers. -

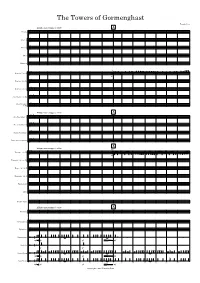

The-Towers-Of-Gormenghast-Web.Pdf

The Towers of Gormenghast Timothy Rees Allegro non troppo q . = 108 A Piccolo ° & 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Flute 1 & 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Flute 2 & 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Oboe & 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Bassoon ? 6 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ¢ 8 Tpt. j j j j j œ œ Clarinet 1 in Bb ° # 6 Œ™ Œ j œ ™ œ j œ ™ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ™ œ j œ ™ œ œ œ œ œ & # 8 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ œ œ œ œ ∑ mf ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Clarinet 2 in Bb # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Clarinet 3 in Bb # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Alto Clarinet in Eb # # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Bass Clarinet # in Bb # 6 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ¢& 8 Allegro non troppo q . = 108 A Alto Saxophone 1 ° # # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Alto Saxophone 2 # # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Tenor Saxophone # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Baritone Saxophone # # # 6 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ¢& 8 A Allegro non troppo q . = 108 solo Trumpet 1 in Bb ° # j j œ œ œ j œ œ œ œ & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Œ™ Œ œ ™ œ œ ™ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ™ œ œ ™ œ œ œ mfœ œ J J J œ J J Trumpet 2 & 3 in Bb # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Horn 1 & 2 in F # & 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Trombone 1 & 2 ? 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Euphonium ? 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Tuba ? 6 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ¢ 8 Double Bass ? 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Allegro non troppo q . = 108 A Timpani °? 6 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ¢ 8 Glockenspiel ° & 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ -

Written Evidence Submitted by the BBC DCMS Select Committee Inquiry Into the Impact of Covid-19 on the DCMS Sectors

Written evidence submitted by the BBC DCMS Select Committee Inquiry into the Impact of Covid-19 on the DCMS Sectors Executive Summary 1. Covid-19 has had a substantial impact on the BBC’s ability to produce programmes and services. Following advice from the WHO, public health organisations and the Government, the BBC closed the production of many programmes and services across its TV and radio output. The cancellation of key broadcasting events, ceasing of productions, and changes to schedules will continue to have an impact on what audiences see and hear across the BBC across the coming months. 2. Like other organisations continuing to operate during this crisis, the BBC has faced operational challenges. We’ve experienced reduced levels of staffing and the huge increase in demand for the BBC’s internal network as over 15,000 colleagues work from home. For those unable to work from home, safety is paramount and we’ve followed Government advice. 3. The BBC Board took the decision to delay changes to the over-75s licence fee from 1 June to 1 August during an unprecedented time. The decision is to be kept under review. 4. In response to Covid-19, the BBC took swift action at the start of the pandemic to repurpose our services and programmes for the benefit of all audiences ensuring we kept the nation informed, educated and entertained. 5. The BBC enhanced our core role to bring trusted news and information to audiences in the UK and around the world in a fast-moving situation, and to counter confusion and misinformation. -

Show-Woman Või Muusikale Pühendunu?

^K, к Show-woman või muusikale pühendunu? Andres Pung: Mida teha, et Eesti muusikute ring kokku ei kuivaks? Jaan-Eik Tulve avab "oma sõnadega" gregoriaani laulu olemust RUDOLF TOBIAS RUDOLF TOBIAS Kaks vaimulikku laulu segakoorile ja orelile Motetid ja vaimulikud laulud segakoorile Zwei geistliche Gesänge fiir gemischten Chor mid Orgel RUDOLF TOBIAS Jenseits des Jordan DES JONA SENDING Klavierauszug Sealpool Jordanit JOONASE LÄHETAMINE Klaviir Mu Nunne l, 10133 Tallinn E-R10-18, L 10-17 tel (o) 644 04 80 INTRO 2/2002 KAVA Muusika seekordses numbris on põhjalikumalt käsitletud Eesti muusikahariduse teemat. Juba ammu on kõneldud 2 Kerttu Soans. "Minust saab see, muusikute töö vähesest väärtustamisest meie muutunud mida ma teen": intervjuu Anu Taliga ühiskonnas. Peagi lõpetavad kooli tuhanded xi Л \j J\ X J—J XJ &-J X JL$ keskharidusega noored, kes seisavad küsimuse ees, 6 Maailmast mida teha edasi. Aasta-aastalt on vähenenud nende IMPRESSIOON hulk, kes otsustavad professionaalse muusiku karjääri 7 Kadri Hunt. Suur muusika suurel reedel kasuks. Muusiku ametit ei peeta enam nii mainekaks ja 8 Elena Lass, Mariliis Valkonen. Seitse tasuvaks kui Vene ajal. Miks see nii on? Selle üle arutleb päeva eesti muusikaga Eesti Muusikaakadeemia õppe- ja teadusprorektor 10 Harry Liivrand. Lesk ja Wiesler 11 Ivalo Randalu. Üks kevadine Andres Pung. Loodetavasti saab Andres Punga artiklist ore li retk hakatust laiem arutelu muusikahariduse teemadel, sest BAGATELLID tegelikult sõltub ju sellest eesti muusikakultuuri tulevik. 14 Eestist LACRYMOSA Reet Marttila, 17 Anneli Remme. Rauno Remme peatoimetaja KONTRAPUNKT 18 Andres Pung. Quo vadis, Eesti muusikaharidus? STÜDIUM Peatoimetaja Reet Marttila [email protected] 24 Anu Kivilo. -

AVANT-POP 101. Here's a List of Works That Helped to Shape Avant-Pop Ideology and Aesthetics, Along with Books, Albums, Films, T

Larry McCaffery AVANT-POP 101. Here's a list of works that helped to shape Avant-Pop ideology and aesthetics, along with books, albums, films, television shows, works of criticism, and other cultural artifacts by the Avant-Pop artists themselves, in roughly chronological order. PRECURSORS: The Odyssey (Homer, c. 700 B.C.). Homer's The Odyssey had it all: a memorable, larger-than-life super-hero (Ulysses); a war grand enough that its name alone (Trojan) is still used to sell condoms; descriptions of travels through exotic places; hideous bad-guys (like the Cyclops) and bad gals (Circe); an enduring love affair (Penelope); a happy ending. Commentators have long regarded The Odyssey as Western literature's first epic and masterpiece. What hasn't been noted until now, however, is that its central features—for instance, its blend of high seriousness with popular culture, a self-conscious narrator, magical realism, appropriation, plagiarism, casual blending of historical materials with purely invented ones, foregrounding of its own artifice, reflexivity, the use of montage and jump cuts—also made it the first postmodern, A-P masterpiece, as well. Choju giga (Bishop Toba, 12th century). Choju giga—or the "Animal Scrolls," as Toba's work is known—was a narrative picture scroll that portrayed, among other things, Walt Disney-style anthropomorphized animals engaged in a series of wild (and occasionally wildly erotic) antics that mocked Toba's own calling (the Buddhist clergy); in its surrealist blend of nightmare and revelry, Toba Choju giga can rightly be said to be the origins not only of cartoons but of an avant-pop aesthetics of cartoon forms that successfully serve "serious" purposes of satire, philosophical speculation and social commentary. -

«Vocabularies» Bobby Mcferrin Vocals Slixs & Friends ~85' Sans

Pops / iPhil Vendredi / Freitag / Friday 16.05.2014 20:00 Grand Auditorium «VOCAbuLarieS» Bobby McFerrin vocals Slixs & friends ~85’ sans entracte / ohne Pause / without intermission «VOCAbuLarieS» Une énergie créative toute particulière se dégage de la rencon- tre magistrale qu’est VOCAbuLarieS, un projet signé par Bobby McFerrin, musicien de jazz et chanteur américain. VOCAbuLa- rieS rompt avec les conventions de la musique a cappella et ras- semble tous les styles musicaux qui ont marqué la carrière de Bobby McFerrin, vainqueur de dix Grammys. On trouve ainsi un mélange de jazz, de classique, de musique d’Afrique, d’Amé- rique latine et d’Inde mais aussi de rhythm’n’blues, de gospel et de pop. Réinventer le vocabulaire de la musique: un défi qui pour Bobby McFerrin est synonyme d’amusement et qui a ryth- mé toute sa vie. VOCAbuLarieS regroupe les innombrables ex- périences musicales du passé de Bobby McFerrin: son timbre fascinant, son incroyable facilité dans l’articulation mais aussi sa passion des voyages. Bobby McFerrin est accompagné ce soir de l’ensemble vocal berlinois Slixs & friends. 2 «VOCAbuLarieS» Mit «VOCAbuLarieS», dem wahrscheinlich aufwändigsten Pro- jekt, das Bobby McFerrin jemals in Angriff genommen hat, ist dem amerikanischen Jazzer und Vokalkünstler ein meisterhafter Zusammenfluss kreativer Energie gelungen. «VOCAbuLarieS» bricht aus den Konventionen der A-cappella-Musik aus und ver- einigt all jene musikalischen Stile, die die Laufbahn des zehnfa- chen Grammy-Gewinners McFerrin geprägt haben: Jazz, Klassik, Musik aus Afrika, Lateinamerika und Indien ebenso wie Rhythm & Blues, Gospel und Pop. Das Vokabular der Musik neu erfinden – für McFerrin ein Spaß, eine Herausforderung, die sein ganzes Le- ben bestimmt hat.