Lionel Wendt: Between Empire and Nation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preparedness for Implementation of Sustainable Development Goals

Preparedness for Implementation of Sustainable Development Goals Report No.PER/2017/2018/SDG/05 National Audit Office Performance Audit Division 1 | P a g e National preparedness for SDG implementation The summary of main observations on National Preparedness for the Implementation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is as follows. 1. The Rapid Integrated Assesment (RIA) is a first step in the process of aligning the country,s national development plan or public Investment programme with SDGs and RIA reveals an uneven alignment between the policy initiatives in the 2017 -2020 Public Investment Programme and the SDG target areas for the economy as (84%) people (80%) planet (58%) peace (42%) and partnership (38%). 2. After deducting debt repayments, the Government has allocated Rs. 440,787 million or 18 percent out of the total national budget of Rs. 2,997,845 million on major projects which identified major targets of relevant SDGs in the year 2018. 3. Sri Lanka had not developed a proper communication strategy on monitoring, follow up, review and reporting on progress towards the implementation of the 2030 agenda. 2 | P a g e Audit at a glance The information gathered from the selected participatory Government institutions have been quantified as follows. Accordingly, Sri Lanka has to pay more attention on almost all of the areas mentioned in the graph for successful implementation of Sustainable Development Goals. 40.0% Alignment of budgets, policies 34.5% and programmes 35.0% Policy integration and coordination 30.0% 28.5% 28.3% 27.0% 26.6% Creating ownership and engaging stakeholders 25.0% 24.0% Identification of resources and 20.5% 21.0% capacities 20.0% Mobilizing partnerships 15.0% Managing risks 10.0% Responsibilities, mechanism and process of monitoring, follow-up 5.0% etc (institutional level) Performance indicators and data 0.0% 3 | P a g e Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................ -

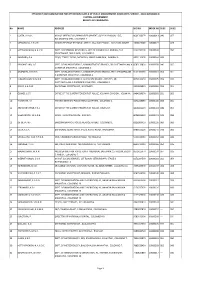

P-50 3A4933 Ceylon Administration Budget

P-50 3A4933 CEYLON ADMINISTRATION BUDGET (ALLOCATIONS & APs) 1953/6-55 BUDGET (ALLOCATIONS & APs) 1955/56 BUDGET (ALLOCATIONS & APs) 1957/56 Budget General 1956/57 PROPERTIES & EQUIPMENT PUBLICITY & PUBLIC RELATIONS - Communist Attack PUBLICITY & PUBLIC RELATIONS - News Clippings PUBLICITY & PUBLIC RELATIONS - General REGISTRATION & STATUS - SEE Current File REPORTS Corres. GENERAL CONFERENCES GENERAL (Cross references to Int'l. Conferences) INDIVIDUALS ABEYSEKERA D.A. AZEES Senator BALASUBRAMANIAM M.D. BANDARANAIKE S.W.R.D. & Wife BARTHOLOMEUSZ Henry CHANDRARATNA M.F. de SARAM de SILVA Bernard de SILVA Dharmasena de SILVA C.C (Irene) de SILVA E.D.E. de SILVA Parakrama DHARMAPALA C.A. DHARMARATNE Lucien D.P. DISSANAYAKE Chandra ELIEZER C.J. & Mrs. Renee GUNEWARDENE R.S.S. IDAIKKADAR N.M. & PONNIAH R.E. ISSADEEN S.S. JAYAWARDENA Padmini (Miss) KANANGARA Senator KOTELAWALA Sir John KULARATNAM K. MAHMUD B. MALASEKARA G.P. NAYAGAM Xavier S. Thani PERERA Hector G.H. PERERA P.A.C RAJASINGHE Sri Kandy P-50 3A4933 INDIVIDUALS: Continued RAMANATHAN Tambeyraj RATNAYAKE Titus RUTNAM Brian SEE: U.S. Ongoing. L. A. Jonas Found. SEMBACUTTIARATCHY Ananda SENEVIRATNE A. SOWER Christopher SUMANADASA P.L. TAMBIMUTTU T. THAMBYAHPILLAY George VARGHESE George SEE INDIA Individual WICKREMASINGHE C.E.L WILSON John P-50 3A4933 CEYLON INDIVIDUALS MISCELLANEOUS ABEYWICKREMA Sumith AGARWAL M.C. AMEER Abdul SEE Moors Islamic Cultural Home Ceylon Org. AMERASINGHE Clarence APPADURAI J. ASEERVATHAM ATHULATHMUDALI Don Martinus SEE Fellowships PHILIPPINE EDUCATION ATTYGALLE Nicholas BALMOND J.H. BARTHOLOMEUSZ L.M. BHATT Niloo BRODIE A.M. CASSIM M.Lafir COORAY Dodwell COORAY Francis COORAY Cissy COORAY Henry COREA C.V.S. DASSENAIKE A. -

Buddha to Krishna

BUDDHA TO KRISHNA This book traces the emergence of modernism in art in South Asia by exploring the work of the iconic artist George Keyt. Closely interwoven with his life, Keyt’s art reflects the struggle and triumph of an artist with very little support or infrastructure. He painted as he lived: full of colour, turmoil and intensity. In this compelling account, the author examines the eventful course of Keyt’s journey, bringing to light unknown and star- tling facts: the personal ferment that Keyt went through because of his tumultuous relationships with women; his close involvement with social events in India and Sri Lanka on the threshold of Independence; and his somewhat angular engagement with artists of the ’43 Group. A collector’s delight, including colour plates and black and white pho- tographs, reminiscences and intimate correspondences, this book reveals the portrait of an artist among the most charismatic figures of our time. This book will be of interest to scholars and researchers of art and art history, modern South Asian studies, sociology, cultural studies as well as art aficionados. Yashodhara Dalmia is an art historian and independent curator based in New Delhi, India. She has written several books including Amrita Sher- Gil: A Life (2006) that have received widespread international acclaim. She is also the author of The Making of Modern Indian Art: The Progressives (2001) and Journeys: Four Generations of Indian Artists (2011). She has curated many art shows, with the most recent being the centenary show ‘Amrita Sher-Gil: The Passionate Quest’ at the National Gallery of Mod- ern Art in New Delhi, Mumbai and Bengaluru in 2014. -

Sri Lanka Journal of South Asian Studies Vol 3. No. 2 November 2017

VOLUME 03 NUMBER 02 NOVEMBER 2017 The Faculty of Arts UNIVERSITY OF JAFFNA, SRI LANKA The Faculty of Arts The Sri Lanka Journal of South Asian Studies Vol.03, No. 02, November 2017 UNIVERSITY OF JAFFNA, SRI LANKA EDITOR’S NOTE The Sri Lanka Journal of South Asian Studies Volume 03 Number 02 November 2017 Volume 03 Number 02 2017 of the Sri Lanka Journal of South Asian Studies continues to deal with research problems related to the South Asian context. As per the vision of the pioneers of the Journal the present issue accommodates six articles. Since its inception in 1978 the Journal has been published with a break in the eighties due to the unrest that prevailed in the Northern and Eastern part of Sri Lanka and it has resumed its publication since 2015. We are unable to publish it on a regular basis due to various problems like lack of facilities, funds and printing due to dearth of professionals with English knowledge. The present volume consists of articles related to maritime intercourse and naval warfare, material culture in archaeology, logical methodology for “Refuting” in Vedanta philosophical tradition, mapping and evaluation of the changes in the land uses of selected river basins in the Northern Province, gender inequality, land rights and socio- economic transformation of women and landscape painting in BritishCeylon. We welcome more articles related to the South Asian context. We hope to continue with regular release of the Journal in future. Dr.K.Shriganeshan Editor. 30.11.2020. The Faculty of Arts The Sri Lanka Journal of South Asian Studies Vol.03, No. -

Sri Lanka a Handbook for US Fulbright Grantees

Welcome to Sri Lanka A Handbook for US Fulbright Grantees US – SL Fulbright Commission (US-SLFC) 55 Abdul Cafoor Mawatha Colombo 3 Sri Lanka Tel: + 94-11-256-4176 Fax: + 94-11-256-4153 Email: [email protected] Website: www.fulbrightsrilanka.com Contents Map of Sri Lanka Welcome Sri Lanka: General Information Facts Sri Lanka: An Overview Educational System Pre-departure Official Grantee Status Obtaining your Visa Travel Things to Bring Health & Medical Insurance Customs Clearance Use of the Diplomatic pouch Preparing for change Recommended Reading/Resources In Country Arrival Welcome-pack Orientation Jet Lag Coping with the Tropical Climate Map of Colombo What’s Where in Colombo Restaurants Transport Housing Money Matters Banks Communication Shipping goods home Health Senior Scholars with Families Things to Do Life and Work in Sri Lanka The US Scholar in Sri Lanka Midterm and Final Reports Shopping Useful Telephone Numbers Your Feedback Appendix: Domestic Notes for Sri Lanka (Compiled by U.S. Fulbrighters 2008-09) The cover depicts a Sandakadaphana; the intricately curved stone base built into the foot of the entrances to buildings of ancient kingdoms. The stone derives it’s Sinhala name from its resemblance to the shape of a half-moon and each motif symbolises a concept in Buddhism. The oldest and most intricately craved Sandakadaphana belongs to the Anuradhapura Kingdom. 2 “My preparation for this long trip unearthed an assortment of information about Sri Lanka that was hard to synthesize – history, religions, laws, nature and ethnic conflict on the one hand and names, advice, maps and travel tips on the other. -

ICOM Committee for Conservation Fifty Years 1967–2017

ICOM Committee for Conservation Fifty Years 1967–2017 Publisher International Council of Museums Committee for Conservation (ICOM-CC) Maison de l’UNESCO 1 rue Miollis 75732 Paris Cedex 15 France Website: www.icom-cc.org Information: [email protected] The Committee for Conservation (ICOM-CC) is a committee of the Interna tional Council of Museums (ICOM) network. Contributing authors Janet Bridgland Joan M. Reifsnyder Editor Carla Nunes Design and prepress Eduardo Pulido Printing MR – Artes Gráficas, Lda. ISBN: 978-92-9012-427-6 © 2017 International Council of Museums Committee for Conservation (ICOM-CC) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system without permission in writing from the copyright holder and publisher. Françoise Flieder 29 December 1929 – 5 April 2017 A member of the International Council of Museums from November 1960, Françoise was an active member of the original Subject Committee for Museum Laboratories and one of the founders of ICOM-CC in 1967. Over the decades she served for three triennial periods on the Directory Board, including as Vice-Chair. She was a Coordinator in the initial nucleus of Working Groups and was deeply involved in the groups’ activities for more than twenty years. Françoise served as Chair of the ICOM-CC Fund at its inception and was a friend and mentor to many among us. She remained an active voting member of ICOM-CC until her death and in late 2016 had been invited to deliver the Triennial Lecture in Copenhagen on the occasion of the Committee’s 50th Anniversary. -

Voluptuous Maidens and Cubist Demons: the "War of Mara" Panel of George Keyt's

VOLUPTUOUS MAIDENS AND CUBIST DEMONS: THE "WAR OF MARA" PANEL OF GEORGE KEYT'S MURALS AT GOTAMI VIHARA, BORELLA, SRI LANKA I 2 Sometime before 1937 , George Keyt wrote the following lines of verse: The desired image continues to subsist on absence, Continues to subsist in me, And presents a masquerade of itself, An assumption of itself, Many moods and sources of its face and voice in things not visible, The breath of feelings which hasten across my path, The contemplation of a shadow. But is it no cause for alarm that returning That shape will find itself a stranger among the emanations') I shall spare the work of absence, The hidden images, the twisted longings ecstatic in entanglement, Desires fading into foliage, The hidden images, the happiness in everlasting retreat from the fear of revelation.3 Prior to the 1930s Keyt had long abandoned his Christian up-bringing and enjoyed his own Buddhist revival." During the 1930s he had begun the process of divorce I This essay is the result of work begun for Professors Jane Daggett Dillenberger and Doug Adams (1947-2007) as part of 'The Devil and Soul in Art and Theology" at the Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, California. The author wishes to acknowledge their support, enthusiasm and pioneering life work in the field of art and religion with deepest admiration and gratitude. The author also thanks Mr. LSD. Pieris of the Sapumal Foundation for readily allowing "Still Life with Mangoes" which is part of the holdings of the Foundation to be reproduced in the journal; Mr. -

Development & Change

ISSN 0972-2661 Review of Development & Change Volume XXIII Number 2 July - December 2018 Special Issue Caste, Craft and Education in India and Sri Lanka Guest Editors Anandhi S. and Aarti Kawlra Anandhi S. An Introduction and Aarti Kawlra Monisha Ahmed Women and Weaving in Ladakh Muhammed Aslam E.S. From Needle to Letters Mark E. Balmforth Riotous Needlework Bidisha Dhar Artisans and Technical Education in Lucknow Shivani Kapoor The Search for ‘Tanner’s Blood’ Sunandan K.N. Politics of Ignoring Bandura Dileepa Technical Education in the Witharana Imagination of the Ceylonese Developmental State Madras Institute of Development Studies REVIEW OF DEVELOPMENT AND CHANGE Madras Institute of Development Studies 79, II Main Road, Gandhinagar, Adyar, Chennai 600 020 Committed to examining diverse aspects of the changes taking place in our society, Review of Development and Change aims to encourage scholarship that perceives problems of development and social change in depth, documents them with care, interprets them with rigour and communicates the findings in a way that is accessible to readers from different backgrounds. Editor Shashanka Bhide Managing Editors Ajit Menon, L. Venkatachalam Associate Editors S. Anandhi, Krishanu Pradhan, K. Jafar Editorial Advisory Board Sunil Amrith, Harvard University, USA Sharad Chari, University of California, Berkeley, USA John Robert Clammer, Jindal School of Liberal Arts and Humanities, India Devika, J, Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram, India Neeraja Gopal Jayal, Jawaharlal Nehru University, India Sisira Jayasuriya, Monash University, Australia K.P. Kalirajan, Australian National University, Australia Ravi Kanbur, Cornell University, USA Anirudh Krishna, Duke University, USA James Manor, University of London, UK Mike Morris, University of Cape Town, South Africa David Mosse, University of London, UK Keijiro Otsuka, Kobe University, Japan Cosmas Ochieng, Boston University, USA Barbara Harriss-White, Oxford University, UK Publication Officer R. -

EB PMAS Class 2 2011 2.Pdf

EFFICIENCY BAR EXAMINATION FOR OFFICERS IN CLASS II OF PUBLIC MANAGEMENT ASSISTANT'S SERVICE - 2011(II)2013(2014) CENTRAL GOVERNMENT RESULTS OF CANDIDATES No NAME ADDRESS NIC NO INDEX NO SUB1 SUB2 1 COSTA, K.A.G.C. M/Y OF DEFENCE & URBAN DEVELOPMENT, SUPPLY DIVISION, 15/5, 860170337V 10000013 040 057 BALADAKSHA MW, COLOMBO 3. 2 MEDAGODA, G.R.U.K. INLAND REVENUE REGIONAL OFFICE, 334, GALLE ROAD, KALUTARA SOUTH. 745802338V 10000027 --- 024 3 HETTIARACHCHI, H.A.S.W. DEPT. OF EXTERNAL RESOURCES, M/Y OF FINANCE & PLANNING, THE 823273010V 10000030 --- 050 SECRETARIAT, 3RD FLOOR, COLOMBO 1. 4 BANDARA, P.A. 230/4, TEMPLE ROAD, BATAPOLA, MADELGAMUWA, GAMPAHA. 682113260V 10000044 ABS --- 5 PRASANTHIKA, L.G. DEPT. OF INLAND REVENUE, ADMINISTRATIVE BRANCH, SRI CHITTAMPALAM A 858513383V 10000058 040 055 GARDINER MAWATHA, COLOMBO 2. 6 ATAPATTU, D.M.D.S. DEPT. OF INLAND REVENUE, ADMINISTRATION BRANCH, SRI CHITTAMPALAM 816130069V 10000061 054 051 A GARDINER MAWATHA, COLOMBO 2. 7 KUMARIHAMI, W.M.S.N. DEPT. OF INLAND REVENUE, ACCOUNTS BRANCH, POB 515, SRI 867010025V 10000075 059 070 CHITTAMPALAM A GARDINER MAWATHA, COLOMBO 2. 8 JENAT, A.A.D.M. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, NEGOMBO. 685060892V 10000089 034 051 9 GOMES, J.S.T. OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE, KELANIYA DIVISION, KELANIYA. 846453857V 10000092 031 052 10 HARSHANI, A.I. FINANCE BRANCH, POLICE HEAD QUARTERS, COLOMBO 1. 827122858V 10000104 064 061 11 ABHAYARATHNE, Y.P.J. OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE, KELANIYA. 841800117V 10000118 049 057 12 WEERAKOON, W.A.D.B. 140/B, THANAYAM PLACE, INGIRIYA. 802893329V 10000121 049 068 13 DE SILVA, W.I. -

Creative and Cultural Industries in Sri Lanka

CREATIVE AND CULTURAL INDUSTRIES IN SRI LANKA Draft Final Report Dilani Hirimuthugodage Ashani Abayasekara Nimesha Dissanayake Manoj Thibbotuwawa Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka 2020 March 1 | Page Acknowledgement This study would not have been possible without the support from several individuals and organizations. We highly appreciate their valuable contribution at various stages of the study and take this opportunity to thank them all. This study is commissioned by the British Council Sri Lanka. The research team wish to extend their acknowledgement to the British Council Sri Lanka for their funding support. As the ownership of the report sits with the British Council. We wish to thank Gill Caldicott and Menika van der Poorten of the British Council Sri Lanka, UK creative sector consultant Shelagh Wright for their continuous support and guidance throughout the study. We greatly appreciate their time and efforts. We gratefully acknowledge the project steering committee members; Vikum Rajapakse, Selyna Peiris, Ruwandika Senanayake, WC Dheerasekera, Alain Parizeau, Shamalee de Silva, Kesara Ratnavibhushana, Dinesh Rajawasam, Sanora Rodrigo, Lee Bazalgette and representatives from the National Enterprise Development Authority. This study would have not been possible if not for those who participated in Focused Group Discussions and Key Informant Interviews. The research team acknowledges the co-operation and contributions from the participants in the following subsectors: literature, publishing, architecture, interior design, fashion design, IT, crafts, photography, film and television, performing and visual arts, and advertising. All the research and support staff members of the IPS, who helped us in various ways and capacities, are also acknowledged. 2 | Page Table of Contents 1. -

An Artifact Assemblage from the Ancient Shipwreck At

AN ARTIFACT ASSEMBLAGE FROM THE ANCIENT SHIPWRECK AT GODAVAYA, SRI LANKA A Thesis by LOYALTY NERY SHI WE TRASTER-LEE Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Chair of Committee, Deborah Carlson Committee Members, Shelley Wachsmann Lilia Campana Head of Department Darryl de Ruiter May 2021 Major Subject: Maritime Archaeology and Conservation Copyright 2021 Loyalty Nerys Shi We Traster-Lee ABSTRACT The Godavaya shipwreck, located off Sri Lanka’s southern coast at a depth of approximately 33 m (110 ft), is presently dated to between the second century B.C.E. and the second century C.E., making it the oldest known shipwreck in the Indian Ocean. The focus of this thesis is a selection of diagnostic artifacts, excavated from this site between 2012 and 2014, consisting of a glass ingot, an unknown glass object, a metal ring, an iron spear, a benchstone, a grindstone, and many ceramic sherds, for a total of 31 artifacts. Its purpose is to attempt to contextualize these items within the Indian Ocean maritime network and Sri Lanka’s mercantile past, through artifact parallels, ancient sources, and previous scholarship. By identifying the likely origin, date, and purpose of each piece, the nature of this cargo and its voyage can be theorized. These in turn will address larger questions of economic activity and technological innovation within the history of the region. Primary sources from ancient cultures provide vital information on Indian Ocean trade connectivity, and the role of maritime networks in structuring Indian Ocean connectivity, and the role of maritime networks in structuring Indian Ocean socioeconomic life. -

NATURAL RESOURCES of SRI LANKA Conditions and Trends

822 LK91 NATURAL RESOURCES OF SRI LANKA Conditions and Trends A REPORT PREPARED FOR THE NATURAL RESOURCES, ENERGY AND SCIENCE AUTHO Sponsored by the United States Agency for International Development NATURAL RESOURCES OF SRI LANKA Conditions and Trends LIBRARY : . INTERNATIONAL REFERENCE CENTRE FOR COMMUNITY WATER SUPPLY AND SANITATION (IRQ LIBRARY, INTERNATIONAL h'L'FERi "NO1£ CEiJRE FOR Ct)MV.u•;•!!rY WATEri SUPPLY AND SALTATION .(IRC) P.O. Box 93H)0. 2509 AD The hi,: Tel. (070) 814911 ext 141/142 RN: lM O^U LO: O jj , i/q i A REPORT PREPARED FOR THE NATURAL RESOURCES, ENERGY AND SCIENCE AUTHORITY OF SRI LANKA. 1991 Editorial Committee Other Contributors Prof. B.A. Abeywickrama Prof.P. Abeygunawardenc Mr. Malcolm F. Baldwin Dr. A.T.P.L. Abeykoon Mr. Malcolm A.B. Jansen Prof. P, Ashton Prof. CM. Madduma Bandara Mr. (J.B.A. Fernando Mr. L.C.A. de S. Wijesinghc Mr. P. Illangovan Major Contributors Dr. R.C. Kumarasuriya Prof. B.A. Abcywickrama Mr. V. Nandakumar Dr. B.K. Basnayake Dr.R.H. Wickramasinghe Ms. N.D. de Zoysa Dr. Kristin Wulfsberg Mr. S. Dimantha Prof. C.B. Dissanayake Prof. H.P.M. Gunasena Editor Mr. Malcolm F. Baldwin Mr. Malcolm A.B, Jansen Copy Editor Ms Pamela Fabian Mr. R.B.M. Koralc Word - Prof. CM. Madduma Bandara Processing Ms Pushpa Iranganie Ms Beryl Mcldcr Mr. K.A.L. Premaratne Cartography Mr. Milton Liyanage Ms D.H. Sadacharan Photography Studio Times, Ltd. Dr. L.R. Sally Mr. Dharmin Samarajeewa Dr. M.U.A. Tcnnekoon Mr. Dominic Sansoni Mr.