Baptists in the Ecumenical Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is Ecumenism*?

What is Ecumenism*? From the Greek meaning “inhabited house.” A worldwide movement among Christians who accept Jesus as Lord and savior and, inspired by the Holy Spirit, seek through prayer, dialogue, and other initiatives to eliminate barriers and move toward the unity Christ willed for his church (Jn 17:21; see also Eph 4:4-5, UR 1-4). Christian communities separated over the Council of Ephesus (431), over the Council of Chalcedon (451), through the East-West schism conventionally dated 1054, at the Reformation in the sixteenth century, and later. Vatican II taught that the true church “subsists in” but is not simply identified with the Catholic Church (LG 8). Belief in Christ and baptism establish a real, if imperfect, union among all Christians (LG 15). In particular, the Orthodox share with Catholics very many elements of faith and sacramental life, including the Eucharist and apostolic succession (see OE 27-30). The Church Unity Octave, eight days of prayer for religious unity of all Christians, which is celebrated each year from January 17 to 25, was stared in 1908 by the founder of the Society of Atonement, Fr. Paul Wattson (1863-1940) when still a member of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States. The following year, with other friars, sisters, and laymen of his Graymoor community, he was received into the Catholic Church * From A Concise Dictionary of Theology. Eds. Gerald O’Collins, S.J. and Edward Farrugia, S.J. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 2000. What is Interreligious Dialogue? First, interreligious dialogue can be described as a kind of “formal conversation” with persons of non- Christian faiths. -

An Ecumenical Journey

An Ecumenical Journey A timeline of the World Council of Churches The Netherlands 1948 Zimbabwe 1998 USA 1954 Canada 1983 Sweden 1968 Australia 1991 India 1961 Kenya 1975 Brazil 2006 General Secretaries of WCC W. A. Visser ’t Hooft (1900-1985) Philip Potter (1921-) Konrad Raiser (1938-) Olav Fykse Tveit (1960-) Term: 1938-1966 Term: 1972-1985 Term: 1993-2003 Term: 2010- A brilliant and visionary Christian leader from the A Methodist pastor, missionary and youth leader from A German theologian who served on the WCC staff under A pastor from the Lutheran communion, Tveit began his Netherlands, Willem Visser ’t Hooft was named WCC general Dominica in the West Indies, Potter was called to several Philip Potter, Raiser once described his ecumenical calling as term of office in January 2010 following seven years as secretary at the 1938 meeting in which the WCC’s process of positions in the WCC. During his mandate as general “a second conversion.” During a sometimes turbulent period leader of the Church of Norway’s council on ecumenical formation began. A Reformed minister, he emphasized the secretary, he insisted on the fundamental unity of Christian for the ecumenical movement, he led the Council as general and international relations. Bringing wide experience in importance of linking the ecumenical movement to enduring witness and Christian service and the correlation of faith secretary in a redefinition of its “Common Understanding inter-religious dialogue, Tveit had also served as co-chair manifestations of the church through the ages. In 1968 he and action. and Vision” and in a fundamental review of the participation of the Palestine Israel Ecumenical Forum core group was elected honorary president of the WCC by the fourth of Orthodox member churches. -

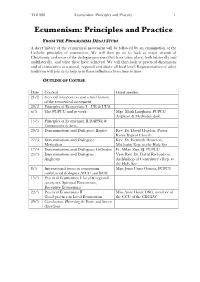

Ecumenism, Principles and Practice

TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 1 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice FROM THE PROGRAMMA DEGLI STUDI A short history of the ecumenical movement will be followed by an examination of the Catholic principles of ecumenism. We will then go on to look at major strands of Christianity and some of the dialogue processes that have taken place, both bilaterally and multilaterally, and what these have achieved. We will then look at practical dimensions and of ecumenism at national, regional and above all local level. Representatives of other traditions will join us to help us in these reflections from time to time. OUTLINE OF COURSE Date Content Guest speaker 21/2 General introduction and a brief history of the ecumenical movement 28/2 Principles of Ecumenism I – UR & UUS 6/3 The PCPCU and its work Mgr. Mark Langham, PCPCU Anglican & Methodist desk. 13/3 Principles of Ecumenism II DAPNE & Communicatio in Sacris 20/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Baptist Rev. Dr. David Hogdon, Pastor, Rome Baptist Church. 27/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Rev. Dr. Kenneth Howcroft, Methodists Methodist Rep. to the Holy See 17/4 Denominations and Dialogues: Orthodox Fr. Milan Zust SJ, PCPCU 24/4 Denominations and Dialogues : Very Rev. Dr. David Richardson, Anglicans Archbishop of Canterbury‘s Rep. to the Holy See 8/5 International issues in ecumenism, Mgr. Juan Usma Gomez, PCPCU multilateral dialogues ,WCC and BEM 15/5 Practical Ecumenism I: local & regional structures, Spiritual Ecumenism, Receptive Ecumenism 22/5 Practical Ecumenism II Miss Anne Doyle DSG, member of Good practice in Local Ecumenism the CCU of the CBCEW 29/5 Conclusion: Harvesting the Fruits and future directions TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 2 Ecumenical Resources CHURCH DOCUMENTS Second Vatican Council Unitatis Redentigratio (1964) PCPCU Directory for the Application of the Principles and Norms of Ecumenism (1993) Pope John Paul II Ut Unum Sint. -

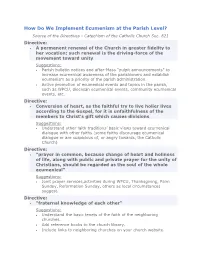

How Do We Implement Ecumenism at the Parish Level? Source of the Directives - Catechism of the Catholic Church Sec

How Do We Implement Ecumenism at the Parish Level? Source of the Directives - Catechism of the Catholic Church Sec. 821 Directive: A permanent renewal of the Church in greater fidelity to her vocation; such renewal is the driving-force of the movement toward unity Suggestions: Parish bulletin notices and after-Mass "pulpit announcements" to increase ecumenical awareness of the parishioners and establish ecumenism as a priority of the parish administration. Active promotion of ecumenical events and topics in the parish, such as WPCU, diocesan ecumenical events, community ecumenical events, etc. Directive: Conversion of heart, as the faithful try to live holier lives according to the Gospel, for it is unfaithfulness of the members to Christ's gift which causes divisions Suggestions: Understand other faith traditions’ basic views toward ecumenical dialogue with other faiths (some faiths discourage ecumenical dialogue or are suspicious of, or angry towards, the Catholic Church) Directive: "prayer in common, because change of heart and holiness of life, along with public and private prayer for the unity of Christians, should be regarded as the soul of the whole ecumenical" Suggestions: Joint prayer services,activities during WPCU, Thanksgiving, Palm Sunday, Reformation Sunday, others as local circumstances suggest. Directive: "fraternal knowledge of each other" Suggestions: Understand the basic tenets of the faith of the neighboring churches. Add reference books to the church library. Include links to neighboring churches on your church website. Directive: "ecumenical formation, of the faithful and especially of priests" Suggestions: For larger parishes, form an ecumenical and interreligious commission. For smaller parishes, appoint an appropriate person as the ecumenical & interfaith liaison. -

Ekklesia and Ecumenism in the Body of Christ: Unity from the Ground-Up

religions Article Ekklesia and Ecumenism in the Body of Christ: Unity from the Ground-Up Anastasia Wendlinder Gonzaga University, 502 East Boone Avenue, Spokane, WA 99258-0102, USA; [email protected] Received: 9 October 2018; Accepted: 22 November 2018; Published: 28 November 2018 Abstract: This article explores the implications for Christian unity from the perspective of the lived faith community, the ekklesia. While bilateral and multilateral dialogues have borne great fruit in bringing Christian denominations closer together, as indeed it will continue to do so, considering how the ecclesiological identity of the faith community both forms and reflects its members may be helpful in moving forward in our ecumenical efforts. This calls for a ground-up approach as opposed to a top-down approach. By “ground-up” it is meant that the starting point for theological reflection on ecumenism begins not with doctrine but with praxis, particularly as it relates to the common believer in the pew. The ecclesiological model “Body of Christ” provides a helpful vocabulary in this exploration for a number of reasons, none the least that it is scripturally-based, presumes diversity and employs concrete imagery relating to everyday life. Further, “Body of Christ” language is used by numerous Christian denominations in their statements of self-identity, regardless of where they lie on the doctrinal or political spectrum. In this article, potential benefits and challenges of this ground-up perspective will be considered, and a way forward will be proposed to promote ecumenical unity across denomination borders. Keywords: ecumenism; ecumenical; ecclesiology; ekklesia; body of Christ; Christianity; denomination; unity-in-diversity; bilateral dialogue; ressourcement; aggiornamento 1. -

The Ecumenism of St. Francis De Sales

STUDIES IN SALESIAN SPIRITUALITY RUTH KLEINMAN The Ecumenism of St. Francis de Sales originally published in Salesian Studies 5/2 (Spring 1968): 42-49 In connection with the present ecumenical movement Saint Francis de Sales in some ways seems an incongruous figure. True, he had the principal charge of a mission to convert an entire province of his native Savoy, and his later biographers have claimed that he was a forerunner of modern missionaries, relying on none but spiritual weapons to move consciences. He also took a great interest in various projects to re-introduce Catholicism into Geneva, and at one point in his life set down what he believed to be a feasible scheme for the general reconciliation of the Protestant churches with Rome. Yet the historian cannot help noting that the saint shared the attitudes of his time concerning the nature of reunion among the churches and the intervention of the state in the process of conversion. These attitudes are no longer comprehensible to many of our own contemporaries, based as they were on conditions and responses three hundred years removed from us. The form of the Reformation Francis de Sales knew best was Calvinism, as he met it in Geneva and the surrounding provinces of France and Savoy. With Lutheranism he seems to have had little if any personal acquaintance, nor did he have anything to say about the Anglican Church. The differences between the Protestant denominations did not concern him greatly. He tended to lump them together, as when he wrote, “We speak indifferently of Luther and Calvin, because we do not believe that their teachings are widely divergent.” As far as he was concerned, Protestantism was heresy, and heresy was rebellion against God, the Church, and usually also the lawful authority of princes. -

Ecumenism in the 21St Century

Ecumenism in the 21st Century Report of the Consultation Convened by the World Council of Churches Chavannes-de-Bogis, Switzerland 30 November to 3 December 2004 World Council of Churches Geneva This is a working document, which has been produced within a tight deadline. It has therefore not been possible to devote time to addi- tional editing, style, etc. © 2005, World Council of Churches 150, route de Ferney, P.O. Box 2100 1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland Web site: http://www.wcc-coe.org Printed in Switzerland Contents 1 Ecumenism in the 21st century: Background to the Consultation 3 Final Statement from the Consultation 12 Summary of Proceedings Appendices 33 I Opening Remarks Presentation by Rev Dr Samuel Kobia 38 II Ecumenism in Process of Transformation Presentation by His Holiness Aram I 46 III Ecumenism and Pentecostals: A Latin American Perspective Presentation by Dr Oscar Corvalán-Vásquez 58 IV Dreams and Visions: Living the Deepening Contradictions of Ecumenism in the 21st Century Presentation by Dr Musimbi Kanyoro 66 V. Mapping the Oikoumene: A Study of Current Ecumenical Structures and Relationships Presentation by Jill Hawkey 81 VI Bible Studies Led by Rev Wesley Ariarajah 85 VII List of Participants 1 Ecumenism in the 21st Century: Background to the Consultation Over the past 50 years, churches throughout the world have established many different ecumenical organisations at the national, regional and global levels in a quest to discover Christian unity and also to assist the churches to respond to the needs of the world. In recent years, questions have been increasingly raised regarding the relationships between these various organi- sations their financial sustainability and whether a reconfiguration of ecu- menical life is necessary in order to meet the challenges of the 21st century. -

Believing in the Church: Why Ecumenism Needs the Invisibility of the Church

religions Article Believing in the Church: Why Ecumenism Needs the Invisibility of the Church Bradford Littlejohn Political Theory, Patrick Henry College, Purcellville, VA 20132, USA; [email protected] Received: 30 November 2018; Accepted: 5 February 2019; Published: 12 February 2019 Abstract: Amidst the plethora of approaches to ecumenical dialogue and church reunion over the last century, a common theme has been the depreciation of the classic Protestant distinction between the “visible” and “invisible” church. Often seen as privileging an abstract predestinarianism over the concrete lives and structures of church communities and underwriting a complacency about division that deprives Christians of any motive to ecumenical endeavor, the concept of the “invisible” church has been widely marginalized in favor of a renewed focus on the “visible” church as the true church. However, I argue that this stress on visible unity creates a pressure toward institutional forms of unity that ultimately privilege Roman Catholic ecclesiologies at the expense of Protestant ones, and thus fails of its ecumenical promise. Renewed attention to Reformational understandings of the relationship between divine grace and human action and the centrality and uniqueness of Christ as the foundation of the church, I argue, dispels some misunderstandings of the church’s “invisibility” and demonstrates the indispensability of the concept. I argue that this Reformational framework, which refuses to accept the empirical divisions of the Church as definitive and summons us to an ecumenism that belongs to the church’s sanctification, provides the best theological ground for ecumenical endeavor. Keywords: ecclesiology; reformation; invisible church; ecumenism; Richard Hooker; John Webster 1. -

The Great Schism of 1054 Ryan Howard Harding University, [email protected]

Tenor of Our Times Volume 1 Article 10 Spring 2012 Unstoppable Force and Immovable Object: The Great Schism of 1054 Ryan Howard Harding University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.harding.edu/tenor Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Howard, Ryan (Spring 2012) "Unstoppable Force and Immovable Object: The Great Schism of 1054," Tenor of Our Times: Vol. 1, Article 10. Available at: https://scholarworks.harding.edu/tenor/vol1/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Humanities at Scholar Works at Harding. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tenor of Our Times by an authorized editor of Scholar Works at Harding. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNSTOPPABLE FORCE AND IMMOVABLE OBJECT: THE GREAT SCHISM OF 1054 by Ryan Howard The year was AD 4 76. Barbarian hordes had ransacked the countryside and cities of the Roman Empire for a century, and Goths had lived alongside Romans in their empire for more than a century before that. On September 4th, the barbarian chieftain Odoacer deposed the last emperor in the western part of the empire, Romulus Augustulus. The Roman rule of the western half of the empire had come to an end. For years, historians declared 4 76 a s the year in which the Roman Empire fell. In recent decades, however, historians have recognized that 4 76 and its events were largely symbolic and symptomatic of a decline in the western half of the empire that was happening long before Odoacer seized power. -

Theology 8 - Catholicism in the World

Theology 8 - Catholicism in the World Course: Theology 8 - Catholicism in the World (Ecumenism and Interreligious Dialogue) Overview: After reviewing the core lessons of previous Bishop Kelley theology courses, students will compare the Catholic faith with that of other Christian communities, with a view toward ecumenism. In the second half of the course, students will compare the Catholic faith with several important world religions outside of Christianity, with a view toward interreligious dialogue. Review of Catholicism Standard 1.1 Sum up the core beliefs and practices of the Catholic faith. Objective 1.1a Identify what makes Catholics Christian in terms of what we believe about God. Objective 1.1b Identify how Catholics’ relating to God (through worship/liturgy/prayer) is Christian and distinctively Catholic. Objective 1.1c Identify the characteristics and organization of the Catholic Church as the Body of Christ. Objective 1.1d Identify how Catholic morality is Christian and distinctively Catholic. Objective 1.1e Analyze how Holy Family Cathedral’s history, art, and architecture reflect the Catholic belief and practice of the Diocese of Tulsa. Ecumenism Standard 2.1 Examine the reasons for and process of ecumenism. Objective 2.1a Identify the scriptural reasons for pursuing ecumenism. Objective 2.1b Analyze the guiding principles of ecumenism, as outlined in Unitatis Redintegratio. Objective 2.1c Evaluate how ecumenism is to be practiced, as outlined in Unitatis Redintegratio. Standard 2.2 Explain how the Catholic Church orthodoxy emerged from early Christian conflicts. Objective 2.2a Identify early ecumenical councils that formed orthodoxy. Objective 2.2b Identify early heresies and schisms that led to or resulted from ecumenical councils. -

THE CHALLENGES and POTENTIAL of ORTHODOX ECUMENICAL DIALOGUE Paraskeve (Eve) Tibbs, Doctoral Student, Fuller Theological Seminary - 2003

THE CHALLENGES AND POTENTIAL OF ORTHODOX ECUMENICAL DIALOGUE Paraskeve (Eve) Tibbs, Doctoral Student, Fuller Theological Seminary - 2003 1. “Ecumenical Baptism” "Do not be afraid. Do not be afraid because of your Orthodoxy; do not be afraid because of being isolated and always in a small minority. Do not make compromises but do not attack others; do not be either defensive or aggressive; simply be yourself." 1 This could have been the advice given to me by my spiritual father as I began taking Master's level classes at Fuller, an Evangelical Seminary, as one of only two Orthodox students (the other a recent convert,) but it was not. It could have been the advice given me prior to preparing my response paper for the Society for Pentecostal Studies, but it was not. This was the wise counsel given to Bishop Kallistos Ware over thirty years ago by Father Amphilochios of Patmos (who had never himself been in the West) upon the approaching inevitability of Bishop Ware's departure from Orthodox monastic life to begin university teaching at Oxford. As a highly esteemed Orthodox teacher and ecumenist, Bishop Ware has obviously followed this advice. From my own extremely limited experience in theology, the Divine reassurance "Do not afraid!" of the Biblical call narratives is appropriate of the "call" to ecumenical dialogue as well. The late Protopresbyter Alexander Schmemann (1921-83) formerly Dean of St. Vladimir's Orthodox Seminary, goes much further than most in calling the ecumenical encounter between Orthodoxy and the West a "failure" which cannot be concealed by the massive presence of Orthodox officials at ecumenical gatherings. -

Anglican Moral Theology and Ecumenical Dialogue

religions Article Anglican Moral Theology and Ecumenical Dialogue Peter Sedgwick 1,2 1 Honorary Research Associate, Cardiff University, Wales CF10 3AT, UK; [email protected] 2 Retired Principal, St. Michael’s College, Cardiff CF5 2YJ, UK Received: 18 August 2017; Accepted: 17 September 2017; Published: 20 September 2017 Abstract: This article argues that there has been conflict in Roman Catholic moral theology since the 1960s. This has overshadowed, but not prevented, ecumenical dialogue between the Roman Catholic and Anglican Communions, especially in ethics. Theologians from the Anglican tradition can help both the debate in Roman Catholic moral theology and the ecumenical impasse. The article examines the contributions of Richard Hooker, Jeremy Taylor, and Kenneth Kirk from 1600–1920, in the area of fundamental moral theology. Keywords: moral theology; ecumenism; Anglican Communion; Roman Catholic Church; moral virtue; Imitation of Christ; moral judgements; moral absolutes; adiaphora/αδιάφoρα There are three arguments which I wish to advance in this article. The first is that Roman Catholic moral theology has been in a state of sustained engagement, and sometimes outright conflict, on the nature of moral theology, and the place of the human agent, since the 1960s. This is at the heart of Joseph Selling’s recent and very valuable book, Reframing Catholic Theological Ethics (Selling 2016). It is this book which was honoured by a conference at Heythrop College, London, in January 2017, both for its own sake and as a way of exploring what the future direction of Catholic theological ethics (or moral theology) might be. I write as an Anglican moral theologian who has long been deeply influenced by Catholic moral theology.