Three Forms of Ecumenism Within Christianity Peter Donnelly Union College - Schenectady, NY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is Ecumenism*?

What is Ecumenism*? From the Greek meaning “inhabited house.” A worldwide movement among Christians who accept Jesus as Lord and savior and, inspired by the Holy Spirit, seek through prayer, dialogue, and other initiatives to eliminate barriers and move toward the unity Christ willed for his church (Jn 17:21; see also Eph 4:4-5, UR 1-4). Christian communities separated over the Council of Ephesus (431), over the Council of Chalcedon (451), through the East-West schism conventionally dated 1054, at the Reformation in the sixteenth century, and later. Vatican II taught that the true church “subsists in” but is not simply identified with the Catholic Church (LG 8). Belief in Christ and baptism establish a real, if imperfect, union among all Christians (LG 15). In particular, the Orthodox share with Catholics very many elements of faith and sacramental life, including the Eucharist and apostolic succession (see OE 27-30). The Church Unity Octave, eight days of prayer for religious unity of all Christians, which is celebrated each year from January 17 to 25, was stared in 1908 by the founder of the Society of Atonement, Fr. Paul Wattson (1863-1940) when still a member of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States. The following year, with other friars, sisters, and laymen of his Graymoor community, he was received into the Catholic Church * From A Concise Dictionary of Theology. Eds. Gerald O’Collins, S.J. and Edward Farrugia, S.J. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 2000. What is Interreligious Dialogue? First, interreligious dialogue can be described as a kind of “formal conversation” with persons of non- Christian faiths. -

An Ecumenical Journey

An Ecumenical Journey A timeline of the World Council of Churches The Netherlands 1948 Zimbabwe 1998 USA 1954 Canada 1983 Sweden 1968 Australia 1991 India 1961 Kenya 1975 Brazil 2006 General Secretaries of WCC W. A. Visser ’t Hooft (1900-1985) Philip Potter (1921-) Konrad Raiser (1938-) Olav Fykse Tveit (1960-) Term: 1938-1966 Term: 1972-1985 Term: 1993-2003 Term: 2010- A brilliant and visionary Christian leader from the A Methodist pastor, missionary and youth leader from A German theologian who served on the WCC staff under A pastor from the Lutheran communion, Tveit began his Netherlands, Willem Visser ’t Hooft was named WCC general Dominica in the West Indies, Potter was called to several Philip Potter, Raiser once described his ecumenical calling as term of office in January 2010 following seven years as secretary at the 1938 meeting in which the WCC’s process of positions in the WCC. During his mandate as general “a second conversion.” During a sometimes turbulent period leader of the Church of Norway’s council on ecumenical formation began. A Reformed minister, he emphasized the secretary, he insisted on the fundamental unity of Christian for the ecumenical movement, he led the Council as general and international relations. Bringing wide experience in importance of linking the ecumenical movement to enduring witness and Christian service and the correlation of faith secretary in a redefinition of its “Common Understanding inter-religious dialogue, Tveit had also served as co-chair manifestations of the church through the ages. In 1968 he and action. and Vision” and in a fundamental review of the participation of the Palestine Israel Ecumenical Forum core group was elected honorary president of the WCC by the fourth of Orthodox member churches. -

Ecumenism, Principles and Practice

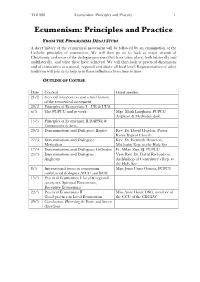

TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 1 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice FROM THE PROGRAMMA DEGLI STUDI A short history of the ecumenical movement will be followed by an examination of the Catholic principles of ecumenism. We will then go on to look at major strands of Christianity and some of the dialogue processes that have taken place, both bilaterally and multilaterally, and what these have achieved. We will then look at practical dimensions and of ecumenism at national, regional and above all local level. Representatives of other traditions will join us to help us in these reflections from time to time. OUTLINE OF COURSE Date Content Guest speaker 21/2 General introduction and a brief history of the ecumenical movement 28/2 Principles of Ecumenism I – UR & UUS 6/3 The PCPCU and its work Mgr. Mark Langham, PCPCU Anglican & Methodist desk. 13/3 Principles of Ecumenism II DAPNE & Communicatio in Sacris 20/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Baptist Rev. Dr. David Hogdon, Pastor, Rome Baptist Church. 27/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Rev. Dr. Kenneth Howcroft, Methodists Methodist Rep. to the Holy See 17/4 Denominations and Dialogues: Orthodox Fr. Milan Zust SJ, PCPCU 24/4 Denominations and Dialogues : Very Rev. Dr. David Richardson, Anglicans Archbishop of Canterbury‘s Rep. to the Holy See 8/5 International issues in ecumenism, Mgr. Juan Usma Gomez, PCPCU multilateral dialogues ,WCC and BEM 15/5 Practical Ecumenism I: local & regional structures, Spiritual Ecumenism, Receptive Ecumenism 22/5 Practical Ecumenism II Miss Anne Doyle DSG, member of Good practice in Local Ecumenism the CCU of the CBCEW 29/5 Conclusion: Harvesting the Fruits and future directions TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 2 Ecumenical Resources CHURCH DOCUMENTS Second Vatican Council Unitatis Redentigratio (1964) PCPCU Directory for the Application of the Principles and Norms of Ecumenism (1993) Pope John Paul II Ut Unum Sint. -

THE CHRISTIAN MESSAGE TODAY Syllabus Knowledge Objectives

PART FIVE THE CHRISTIAN MESSAGE TODAY Syllabus Knowledge Objectives • have a knowledge of current developments in the ecumenical movement • be able to name and recognise contemporary trends and challenges in Christianity. Understanding • have an understanding of the importance of origins in understanding the present and offering insight into future situations • be aware of the historical nature of Christianity and the role of the cultural context in the shaping of belief and practice from ancient times to the present day • understand the relationship between faith and culture • have an insight into the nature of Christian community life and ethical vision. Skills • recognise moments of adaptation and reform in the Christian tradition • analyse these moments in the light of Christian origins • develop critical awareness of their own/local Christian communities in the light of the original message of Jesus and life in the first communities. Attitudes • appreciation of the place of cultural context in the preaching and development of the Christian traditions • appreciation of the significance of the life, teaching, death, and resurrection of Jesus for the first Christians, for Christians today, and for the wider community • openness to diverse expressions of Christianity. Topic: 5.1 Interpreting the message today Procedure Description of content: In the case of one of the following, explore how the teaching and work of one Christian denomination sees itself as carrying on the mission of Jesus • Christians faced with violence, intolerance, and sectarianism • Christian understanding of a just and inclusive society • Christians and the use and sharing of the earth’s resources • Christian faith and victory over death • Christian community life today: structures and authority. -

Policy Statement on Interdenominational

Kairos Prison Ministry International, Inc. Interdenominational, Diversity, and Spiritual Unity Policy All Kairos Volunteers should know and agree with the Kairos Mission, Vision, Core Values and Statement of Faith. Each Kairos leader and team member must read and follow the applicable program manual. Kairos is a ministry of persons drawn from a broad range of Christian Churches which includes denominational, racial and age diversity. We expect all God’s people to be treated with respect, love, integrity and equality. Each team member must understand the importance of Kairos as a ministry of the church - a Ministry called by Jesus Christ to serve in the correctional institution and the lives of their relatives and friends. Kairos Prison Ministry is an interdenominational Christian ministry, commonly referred to as ecumenical. Ecumenical is promoting or relating to unity among the world's Christian churches. In Kairos, we are Christians who believe in the Holy Trinity and honor and live the teaching of the Bible and our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ. The ecumenical nature of Kairos Prison Ministry must be upheld which requires that team members come from a variety of denominations and that all volunteers refrain from activities that are practiced by their particular denomination, in contrast to others, while serving as a Kairos volunteer. Kairos Prison Ministry International presents only broad based, mainstream Christian teachings which we, as Christians, hold as ‘common ground.’ These teachings are built primarily around Jesus Christ’s unconditional love. We recognize our limitations, acknowledging that with God’s help, we can make a difference. Kairos volunteers present Christ’s love, understanding, forgiveness and acceptance. -

Protestantism, Liberalism, and Racial Equality

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Honors Theses Lee Honors College 2-7-2014 Protestantism, Liberalism, and Racial Equality Abraham Uppal Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Uppal, Abraham, "Protestantism, Liberalism, and Racial Equality" (2014). Honors Theses. 2393. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses/2393 This Honors Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Lee Honors College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WESTERN MICHIGAN UNIVERSITY PROTESTANTISM, LIBERALISM, AND RACIAL EQUALITY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE HONORS COLLEGE BY ABRAHAM UPPAL KALAMAZOO, MICHIGAN December 2013 1 2 3 This paper was greatly helped by Dr. Peter Wielhouwer 4 CONTENTS Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION General Introduction Research Question Method Chapter Map PART 1. HISTORY OF PROTESTANTISM PART 2. ANALYSIS OF U.S. PROTESTANT SUBFAMILIES 2. MAINLINE PROTESTANT CHURCHES Lutherans Reformed Anglicans Presbyterians Methodists United Church of Christ American Baptist Churches USA 5 3. EVANGELICAL CHRISTIAN CHURCHES Baptists Pentecostals Anabaptists 4. DATA 5. AFRICAN-AMERICAN PROTESTANTISM 6. WHITE SUPREMACIST CHRISTIAN MOVEMENTS PART 3. IS JESUS A LIBERAL OR A CONSERVATIVE, BASED ON THE GOSPELS? 7. CONCLUSIONS REFERENCE LIST 6 TABLES Table 1. Affiliation Tendency Among Protestant Subfamilies 2. Affiliation Percentage among Protestant Subfamilies 3. Racial Views by Subfamily 7 PREFACE In this paper, I will examine liberalism in Protestantism. Liberals who are Protestant, Mainline Protestants, are an interesting group who are different from the conservative, Evangelical Christian crowd. -

How Do We Implement Ecumenism at the Parish Level? Source of the Directives - Catechism of the Catholic Church Sec

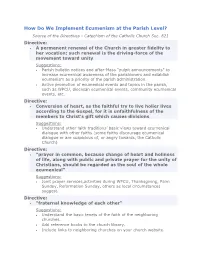

How Do We Implement Ecumenism at the Parish Level? Source of the Directives - Catechism of the Catholic Church Sec. 821 Directive: A permanent renewal of the Church in greater fidelity to her vocation; such renewal is the driving-force of the movement toward unity Suggestions: Parish bulletin notices and after-Mass "pulpit announcements" to increase ecumenical awareness of the parishioners and establish ecumenism as a priority of the parish administration. Active promotion of ecumenical events and topics in the parish, such as WPCU, diocesan ecumenical events, community ecumenical events, etc. Directive: Conversion of heart, as the faithful try to live holier lives according to the Gospel, for it is unfaithfulness of the members to Christ's gift which causes divisions Suggestions: Understand other faith traditions’ basic views toward ecumenical dialogue with other faiths (some faiths discourage ecumenical dialogue or are suspicious of, or angry towards, the Catholic Church) Directive: "prayer in common, because change of heart and holiness of life, along with public and private prayer for the unity of Christians, should be regarded as the soul of the whole ecumenical" Suggestions: Joint prayer services,activities during WPCU, Thanksgiving, Palm Sunday, Reformation Sunday, others as local circumstances suggest. Directive: "fraternal knowledge of each other" Suggestions: Understand the basic tenets of the faith of the neighboring churches. Add reference books to the church library. Include links to neighboring churches on your church website. Directive: "ecumenical formation, of the faithful and especially of priests" Suggestions: For larger parishes, form an ecumenical and interreligious commission. For smaller parishes, appoint an appropriate person as the ecumenical & interfaith liaison. -

The Baptist Tradition and Religious Freedom: Recent Trajectories

THE BAPTIST TRADITION AND RELIGIOUS FREEDOM: RECENT TRAJECTORIES by Samuel Kyle Brassell A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnel Barksdale Honors College. Oxford May 2019 Approved by _______________________________ Advisor: Professor Sarah Moses _______________________________ Reader: Professor Amy McDowell _______________________________ Reader: Professor Steven Skultety ii © 2019 Samuel Kyle Brassell ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College for providing funding to travel to the Society of Christian Ethics conference in Louisville to attend presentations and meet scholars to assist with my research. iii ABSTRACT SAMUEL KYLE BRASSELL: The Baptist Tradition and Religious Freedom: Recent Trajectories For my thesis, I have focused on the recent religious freedom bill passed in Mississippi and the arguments and influences Southern Baptists have had on the bill. I used the list of resolutions passed by the Southern Baptist Convention to trace the history and development of Southern Baptist thought on the subject of religious freedom. I consulted outside scholarly works to examine the history of the Baptist tradition and how that history has influenced modern day arguments. I compared these texts to the wording of the Mississippi bill. After conducting this research, I found that the Southern Baptist tradition and ethical thought are reflected in the wording of the Mississippi bill. I found that the large percentage of the Mississippi population comprised of Southern Baptists holds a large amount of political power in the state, and this power was used to pass a law reflecting their ethical positions. -

A Public Debate on Cyril of Alexandria's Views on The

International Journal of the Classical Tradition https://doi.org/10.1007/s12138-019-00551-1 ARTICLE A Public Debate on Cyril of Alexandria’s Views on the Procession of the Holy Spirit in Seventeenth‑Century Constantinople: the Jesuit Reaction to Nicodemos Metaxas’s Greek Editions Nil Palabıyık1 © The Author(s) 2020 On a September afternoon in 1627, crowds gathered at the library of the Jesuit resi- dence in Constantinople to witness a lively public discussion between two repre- sentatives of the Roman Catholic Church concerning Cyril of Alexandria’s views on the procession of the Holy Spirit.1 It is interesting to see that a ffth-century church father’s writings in the context of a dispute dating back to the sixth century were still considered politically relevant, socially infuential and theologically compelling in seventeenth-century Constantinople. The primary aim of this rather ostentatious gathering was to adopt and promote a diferent (according to Eastern Christians an ‘erroneous’) viewpoint on Cyril of Alexandria’s writings on the procession of the Holy Spirit, and thereby to present a counter-argument to that of the Eastern Church. The Jesuit dispute ultimately targeted the theological stance and the reputation of Cyril Lucaris (1572–1638), the ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople and the of- cial head of the populous Greek Orthodox millet of the Ottoman Empire. 1 Cyril of Alexandria’s opinion on this question is still controversial, but lies beyond the scope of this article. For a succinct overview, see A. E. Siecienski, The Filioque: History of a Doctrinal Controversy, Oxford, 2010, pp. 47–50. -

Ekklesia and Ecumenism in the Body of Christ: Unity from the Ground-Up

religions Article Ekklesia and Ecumenism in the Body of Christ: Unity from the Ground-Up Anastasia Wendlinder Gonzaga University, 502 East Boone Avenue, Spokane, WA 99258-0102, USA; [email protected] Received: 9 October 2018; Accepted: 22 November 2018; Published: 28 November 2018 Abstract: This article explores the implications for Christian unity from the perspective of the lived faith community, the ekklesia. While bilateral and multilateral dialogues have borne great fruit in bringing Christian denominations closer together, as indeed it will continue to do so, considering how the ecclesiological identity of the faith community both forms and reflects its members may be helpful in moving forward in our ecumenical efforts. This calls for a ground-up approach as opposed to a top-down approach. By “ground-up” it is meant that the starting point for theological reflection on ecumenism begins not with doctrine but with praxis, particularly as it relates to the common believer in the pew. The ecclesiological model “Body of Christ” provides a helpful vocabulary in this exploration for a number of reasons, none the least that it is scripturally-based, presumes diversity and employs concrete imagery relating to everyday life. Further, “Body of Christ” language is used by numerous Christian denominations in their statements of self-identity, regardless of where they lie on the doctrinal or political spectrum. In this article, potential benefits and challenges of this ground-up perspective will be considered, and a way forward will be proposed to promote ecumenical unity across denomination borders. Keywords: ecumenism; ecumenical; ecclesiology; ekklesia; body of Christ; Christianity; denomination; unity-in-diversity; bilateral dialogue; ressourcement; aggiornamento 1. -

Orthodox Mission Methods: a Comparative Study

ORTHODOX MISSION METHODS: A COMPARATIVE STUDY by STEPHEN TROMP WYNN HAYES submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF THEOLOGY in the subject of MISSIOLOGY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA Promoter: Professor W.A. Saayman JUNE 1998 Page 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the University of South Africa, who awarded the Chancellor's Scholarship, which enabled me to travel to Russia, the USA and Kenya to do research. I would also like to thank the Orthodox Christian Mission Center, of St Augustine, Florida, for their financial help in attending the International Orthodox Christian Mission Conference at Holy Cross Seminary, Brookline, MA, in August 1996. To Fr Thomas Hopko, and the staff of St Vladimir's Seminary in New York, for allowing me to stay at the seminary and use the library facilities. The St Tikhon's Institute in Moscow, and its Rector, Fr Vladimir Vorobiev and the staff, for their help with visa applications, and for their patience in giving me information in interviews. To the Danilov Monastery, for their help with accom modation while I was in Moscow, and to Fr Anatoly Frolov and all the parishioners of St Tikhon's Church in Klin, for giving me an insight into Orthodox life and mission in a small town parish. To Metropolitan Makarios of Zimbabwe, and the staff and students of the Makarios III Orthodox Seminary at Riruta, Kenya, for their hospitality and their readiness to help me get the information I needed. To the Pokrov Foundation in Bulgaria, for their hospitality and help, and to the Monastery of St John the Forerunner in Karea, Athens, and many others in that city who helped me with my research in Greece. -

Jordan 2019 International Religious Freedom Report

JORDAN 2019 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution declares Islam the religion of the state but safeguards “the free exercise of all forms of worship and religious rites” as long as these are consistent with public order and morality. It stipulates there shall be no discrimination based on religion. It does not address the right to convert to another faith, nor are there penalties under civil law for doing so. According to the constitution, matters concerning the personal and family status of Muslims come under the jurisdiction of sharia courts. Under sharia, converts from Islam are still considered Muslims and are subject to sharia but are regarded as apostates. Seven of the 11 recognized Christian groups have religious courts to address such personal status matters for their members. In April parliament ratified amendments to the Personal Status Law (PSL), stipulating that mothers, regardless of religious background, should retain custody of their children until age 18. The government continued to deny official recognition to some religious groups, including Baha’is and Jehovah’s Witnesses. On August 1, the government temporarily closed Aaron’s Tomb, a religious site near Petra popular with tourists, after photographs and videos appeared on social media showing a group of Jewish tourists praying at the site. Members of some unregistered groups continued to face problems registering their marriages and the religious affiliation of their children, and also renewing their residency permits. The government continued to monitor mosque sermons and required that preachers refrain from political commentary and adhere to approved themes and texts during Friday sermons.