Evangelicals, Ecumenism and Unity: a Case Study of the Evangelical Alliancel Ian Randall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evangelicalism and the Church of England in the Twentieth Century

STUDIES IN MODERN BRITISH RELIGIOUS HISTORY Volume 31 EVANGELICALISM AND THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY REFORM, RESISTANCE AND RENEWAL Evangelicalism and the Church.indb 1 25/07/2014 10:00 STUDIES IN MODERN BRITISH RELIGIOUS HISTORY ISSN: 1464-6625 General editors Stephen Taylor – Durham University Arthur Burns – King’s College London Kenneth Fincham – University of Kent This series aims to differentiate ‘religious history’ from the narrow confines of church history, investigating not only the social and cultural history of reli- gion, but also theological, political and institutional themes, while remaining sensitive to the wider historical context; it thus advances an understanding of the importance of religion for the history of modern Britain, covering all periods of British history since the Reformation. Previously published volumes in this series are listed at the back of this volume. Evangelicalism and the Church.indb 2 25/07/2014 10:00 EVANGELICALISM AND THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY REFORM, RESISTANCE AND RENEWAL EDITED BY ANDREW ATHERSTONE AND JOHN MAIDEN THE BOYDELL PRESS Evangelicalism and the Church.indb 3 25/07/2014 10:00 © Contributors 2014 All Rights Reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner First published 2014 The Boydell Press, Woodbridge ISBN 978-1-84383-911-8 The Boydell Press is an imprint of Boydell & Brewer Ltd PO Box 9, Woodbridge, Suffolk IP12 3DF, UK and of Boydell & Brewer Inc. -

The Empty Tomb

content regulars Vol 24 No 299 April 2021 6 gHOSTLy cOunSEL 3 LEAD STORy 20 views, reviews & previews AnDy HAWES A Missioner to the catholic on the importance of the church Movement BOOkS: Christopher Smith on Philip North introduces this Wagner 14 LOST SuffOLk cHuRcHES Jack Allen on Disability in important role Medieval Christianity EDITORIAL 18 Benji Tyler on Being Yourself BISHOPS Of THE SOcIETy 35 4 We need to talk about Andy Hawes on Chroni - safeguarding cles from a Monastery A P RIEST 17 APRIL DIARy raises some important issues 27 In it from the start urifer emerges 5 The Empty Tomb ALAn THuRLOW in March’s New Directions 19 THE WAy WE LIvE nOW JOHn TWISLETOn cHRISTOPHER SMITH considers the Resurrection 29 An earthly story reflects on story and faith 7 The Journal of Record DEnIS DESERT explores the parable 25 BOOk Of THE MOnTH WILLIAM DAvAgE MIcHAEL LAngRISH writes for New Directions 29 Psachal Joy, Reveal Today on Benedict XVI An Easter Hymn 8 It’s a Sin 33 fAITH Of OuR fATHERS EDWARD DOWLER 30 Poor fred…Really? ARTHuR MIDDLETOn reviews the important series Ann gEORgE on Dogma, Devotion and Life travels with her brother 9 from the Archives 34 TOucHIng PLAcE We look back over 300 editions of 31 England’s Saint Holy Trinity, Bosbury Herefordshire New Directions JOHn gAyfORD 12 Learning to Ride Bicycles at champions Edward the Confessor Pusey House 35 The fulham Holy Week JAck nIcHOLSOn festival writes from Oxford 20 Still no exhibitions OWEn HIggS looks at mission E R The East End of St Mary's E G V Willesden (Photo by Fr A O Christopher Phillips SSC) M I C Easter Chicks knitted by the outreach team at Articles are published in New Directions because they are thought likely to be of interest to St Saviour's Eastbourne, they will be distributed to readers. -

What Is Ecumenism*?

What is Ecumenism*? From the Greek meaning “inhabited house.” A worldwide movement among Christians who accept Jesus as Lord and savior and, inspired by the Holy Spirit, seek through prayer, dialogue, and other initiatives to eliminate barriers and move toward the unity Christ willed for his church (Jn 17:21; see also Eph 4:4-5, UR 1-4). Christian communities separated over the Council of Ephesus (431), over the Council of Chalcedon (451), through the East-West schism conventionally dated 1054, at the Reformation in the sixteenth century, and later. Vatican II taught that the true church “subsists in” but is not simply identified with the Catholic Church (LG 8). Belief in Christ and baptism establish a real, if imperfect, union among all Christians (LG 15). In particular, the Orthodox share with Catholics very many elements of faith and sacramental life, including the Eucharist and apostolic succession (see OE 27-30). The Church Unity Octave, eight days of prayer for religious unity of all Christians, which is celebrated each year from January 17 to 25, was stared in 1908 by the founder of the Society of Atonement, Fr. Paul Wattson (1863-1940) when still a member of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States. The following year, with other friars, sisters, and laymen of his Graymoor community, he was received into the Catholic Church * From A Concise Dictionary of Theology. Eds. Gerald O’Collins, S.J. and Edward Farrugia, S.J. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 2000. What is Interreligious Dialogue? First, interreligious dialogue can be described as a kind of “formal conversation” with persons of non- Christian faiths. -

An Ecumenical Journey

An Ecumenical Journey A timeline of the World Council of Churches The Netherlands 1948 Zimbabwe 1998 USA 1954 Canada 1983 Sweden 1968 Australia 1991 India 1961 Kenya 1975 Brazil 2006 General Secretaries of WCC W. A. Visser ’t Hooft (1900-1985) Philip Potter (1921-) Konrad Raiser (1938-) Olav Fykse Tveit (1960-) Term: 1938-1966 Term: 1972-1985 Term: 1993-2003 Term: 2010- A brilliant and visionary Christian leader from the A Methodist pastor, missionary and youth leader from A German theologian who served on the WCC staff under A pastor from the Lutheran communion, Tveit began his Netherlands, Willem Visser ’t Hooft was named WCC general Dominica in the West Indies, Potter was called to several Philip Potter, Raiser once described his ecumenical calling as term of office in January 2010 following seven years as secretary at the 1938 meeting in which the WCC’s process of positions in the WCC. During his mandate as general “a second conversion.” During a sometimes turbulent period leader of the Church of Norway’s council on ecumenical formation began. A Reformed minister, he emphasized the secretary, he insisted on the fundamental unity of Christian for the ecumenical movement, he led the Council as general and international relations. Bringing wide experience in importance of linking the ecumenical movement to enduring witness and Christian service and the correlation of faith secretary in a redefinition of its “Common Understanding inter-religious dialogue, Tveit had also served as co-chair manifestations of the church through the ages. In 1968 he and action. and Vision” and in a fundamental review of the participation of the Palestine Israel Ecumenical Forum core group was elected honorary president of the WCC by the fourth of Orthodox member churches. -

Ecumenism, Principles and Practice

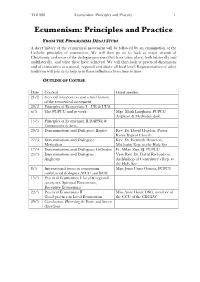

TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 1 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice FROM THE PROGRAMMA DEGLI STUDI A short history of the ecumenical movement will be followed by an examination of the Catholic principles of ecumenism. We will then go on to look at major strands of Christianity and some of the dialogue processes that have taken place, both bilaterally and multilaterally, and what these have achieved. We will then look at practical dimensions and of ecumenism at national, regional and above all local level. Representatives of other traditions will join us to help us in these reflections from time to time. OUTLINE OF COURSE Date Content Guest speaker 21/2 General introduction and a brief history of the ecumenical movement 28/2 Principles of Ecumenism I – UR & UUS 6/3 The PCPCU and its work Mgr. Mark Langham, PCPCU Anglican & Methodist desk. 13/3 Principles of Ecumenism II DAPNE & Communicatio in Sacris 20/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Baptist Rev. Dr. David Hogdon, Pastor, Rome Baptist Church. 27/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Rev. Dr. Kenneth Howcroft, Methodists Methodist Rep. to the Holy See 17/4 Denominations and Dialogues: Orthodox Fr. Milan Zust SJ, PCPCU 24/4 Denominations and Dialogues : Very Rev. Dr. David Richardson, Anglicans Archbishop of Canterbury‘s Rep. to the Holy See 8/5 International issues in ecumenism, Mgr. Juan Usma Gomez, PCPCU multilateral dialogues ,WCC and BEM 15/5 Practical Ecumenism I: local & regional structures, Spiritual Ecumenism, Receptive Ecumenism 22/5 Practical Ecumenism II Miss Anne Doyle DSG, member of Good practice in Local Ecumenism the CCU of the CBCEW 29/5 Conclusion: Harvesting the Fruits and future directions TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 2 Ecumenical Resources CHURCH DOCUMENTS Second Vatican Council Unitatis Redentigratio (1964) PCPCU Directory for the Application of the Principles and Norms of Ecumenism (1993) Pope John Paul II Ut Unum Sint. -

Lambeth Daily 28Th July 1998

The LambethDaily ISSUE No.8 TUESDAY JULY 28 1998 OFFICIAL NEWSPAPER OF THE 1998 LAMBETH CONFERENCE TODAY’S KEY EVENTS What’s 7.00am Eucharist Mission top of Holy Land serves as 9.00am Coaches leave University campus for Lambeth Palace 12.00pm Lunch at Lambeth Palace agenda for cooking? 2.45pm Coaches depart Lambeth Palace for Buckingham Palace c. 6.00pm Coaches depart Buckingham Palace for Festival Pier College laboratory An avalanche of food c. 6.30pm Embarkation on Bateaux Mouche Japanese Church 6.45 - 9.30pm Boat trip along the Thames Page 3 Page 4 9.30pm Coaches depart Barrier Pier for University campus Page 3 Bishop Spong apologises to Africans by David Skidmore scientific theory. Bishop Spong has been in the n escalating rift between con- crosshairs of conservatives since last Aservative African bishops and November when he engaged in a Bishop John Spong (Newark, US) caustic exchange of letters with the appears headed for a truce. In an Archbishop of Canterbury over interview on Saturday Bishop homosexuality. In May he pub- Spong expressed regret for his ear- lished his latest book, Why Chris- Bishops on the run lier statements characterising tianity Must Change or Die, which African views on the Bible as questions the validity of a physical Bishops swapped purple for whites as teams captained by Bishop Michael “superstitious.” resurrection and other central prin- Photos: Anglican World/Jeff Sells Nazir-Ali (Rochester, England) and Bishop Arthur Malcolm (North Queens- Bishop Spong came under fire ciples of the creeds. land,Australia) met for a cricket match on Sunday afternoon. -

Protestants, Evangelicals, and the Religious Order: Christianity and Political Conservatism in the United Kingdom and United States from 1530 to 1950

Protestants, Evangelicals, and the Religious Order: Christianity and Political Conservatism in the United Kingdom and United States from 1530 to 1950 An Honors Thesis Presented by Duncan Mayer Robb to Curriculum and Honors Committee Department of Political Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a degree with honors of Bachelor of Arts University of Oregon June 2009 Thesis Advisor: Dr. Craig Parsons Second Reader: Dr. Joseph Lowndes 2 The British monarch holds a number of titles and distinctions. “Defender of the Faith and Supreme Governor of the Church of England” is only one of them and carries little practical importance – no more than “Commandant-in-Chief of the Royal Air Force” or “Lord High Admiral of the Royal Navy.” But, the former distinction, bestowed upon all Sovereigns of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, is perhaps the most obvious example of the tie that exists between Church and State there. However, while this link is born of a historic symbiotic relationship between the Church of England and British government, politics and public life today have a distant association with religious matters. Prayer in schools, though mandated by British common law, is often not practiced daily, weekly, or even monthly (Lords 19 Apr. 2007). While Church of England bishops do sit in the House of Lords, which indeed possesses some real power, most notably derived from its judicial authority roughly equivalent to the American Supreme Court, the upper house’s power and influence pales in comparison to that of the House of Commons across the hall (Nash). -

How Do We Implement Ecumenism at the Parish Level? Source of the Directives - Catechism of the Catholic Church Sec

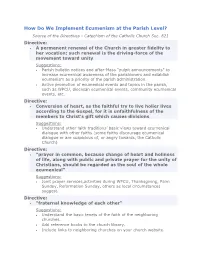

How Do We Implement Ecumenism at the Parish Level? Source of the Directives - Catechism of the Catholic Church Sec. 821 Directive: A permanent renewal of the Church in greater fidelity to her vocation; such renewal is the driving-force of the movement toward unity Suggestions: Parish bulletin notices and after-Mass "pulpit announcements" to increase ecumenical awareness of the parishioners and establish ecumenism as a priority of the parish administration. Active promotion of ecumenical events and topics in the parish, such as WPCU, diocesan ecumenical events, community ecumenical events, etc. Directive: Conversion of heart, as the faithful try to live holier lives according to the Gospel, for it is unfaithfulness of the members to Christ's gift which causes divisions Suggestions: Understand other faith traditions’ basic views toward ecumenical dialogue with other faiths (some faiths discourage ecumenical dialogue or are suspicious of, or angry towards, the Catholic Church) Directive: "prayer in common, because change of heart and holiness of life, along with public and private prayer for the unity of Christians, should be regarded as the soul of the whole ecumenical" Suggestions: Joint prayer services,activities during WPCU, Thanksgiving, Palm Sunday, Reformation Sunday, others as local circumstances suggest. Directive: "fraternal knowledge of each other" Suggestions: Understand the basic tenets of the faith of the neighboring churches. Add reference books to the church library. Include links to neighboring churches on your church website. Directive: "ecumenical formation, of the faithful and especially of priests" Suggestions: For larger parishes, form an ecumenical and interreligious commission. For smaller parishes, appoint an appropriate person as the ecumenical & interfaith liaison. -

Ordination of Deacons by the Bishop of London Assisted by the Area Bishops, the Bishop Suffragan and the Honorary Assistant Bishops

Eucharist with the Ordination of Deacons by the Bishop of London assisted by the Area Bishops, the Bishop Suffragan and the Honorary Assistant Bishops Eve of St Peter Saturday 28th June 2014 3 pm WELCOME TO ST PAUL’S CATHEDRAL Today thirty-five women and men are ordained to serve as deacons in the Church of God. All Christians are called to serve Christ as they live their daily lives. Deacons are called to serve in a particular way, exercising the ministry of ‘diakonia’ – servanthood. We are a Christian church within the Anglican tradition (Church of England) and we welcome people of all Christian traditions as well as people of other faiths and people of little or no faith. Christian worship has been offered to God here for over 1400 years. By worshipping with us today, you become part of that living tradition. Our regular worshippers, supported by nearly 150 members of staff and a large number of volunteers, make up the cathedral community. We are committed to the diversity, equal opportunities and personal and spiritual development of all who work and worship here because we are followers of Jesus Christ. We are a Fairtrade Cathedral and use fairly traded communion wine at all celebrations of the Eucharist. This order of service is printed on sustainably-produced paper. You are welcome to take it away with you but, if you would like us to recycle it for you, please leave it on your seat. Thank you for being with us today. If you need any help, please ask a member of staff. -

Peter Webster, 'Evangelicals, Culture and the Arts'

Peter Webster, ‘Evangelicals, culture and the arts’ Chapter 14 of Andrew Atherstone and David Ceri Jones (eds), The Routledge Research Companion to the History of Evangelicalism (Abingdon, Routledge, 2019), pp.232- 247. Available via https://peterwebster.me This is the text as accepted by the publisher after peer review, but before copy-editing and typesetting. The version of record is available via https://www.routledge.com/The-Routledge- Research-Companion-to-the-History-of-Evangelicalism/Atherstone- Jones/p/book/9781472438928 ISBN:9781472438928 Evangelicals, culture and the arts Peter Webster One evening in the early 1960s Michael Saward, curate of St Margaret’s Edgware, a thriving evangelical Anglican parish in north London, went to the Royal Festival Hall to hear the aged Otto Klemperer conduct Beethoven. As the Polish violinist Henryk Szeryng played the Violin Concerto, Saward unexpectedly found himself ‘sitting (or so it seemed) a yard above my seat and experiencing what I can only describe as perhaps twenty minutes of orgasmic ecstasy. Heaven had touched earth in the Royal Festival Hall.’ Saward came later came to view the experience as the third instalment in a ‘trinity of revelation . a taste of [God’s] work as creator of all that is beautiful, dynamic and worthy of praise . speaking of his majesty in the universe which he has made, goes on sustaining, and fills with his life force, the Holy Spirit, who draws out of humanity an infinite range of talent, skill and glorious creativity in artistic works.'1 Saward’s words were part of a memoir and not a work of theology, but they challenge many received views of the relationship between evangelicals and the arts. -

Ekklesia and Ecumenism in the Body of Christ: Unity from the Ground-Up

religions Article Ekklesia and Ecumenism in the Body of Christ: Unity from the Ground-Up Anastasia Wendlinder Gonzaga University, 502 East Boone Avenue, Spokane, WA 99258-0102, USA; [email protected] Received: 9 October 2018; Accepted: 22 November 2018; Published: 28 November 2018 Abstract: This article explores the implications for Christian unity from the perspective of the lived faith community, the ekklesia. While bilateral and multilateral dialogues have borne great fruit in bringing Christian denominations closer together, as indeed it will continue to do so, considering how the ecclesiological identity of the faith community both forms and reflects its members may be helpful in moving forward in our ecumenical efforts. This calls for a ground-up approach as opposed to a top-down approach. By “ground-up” it is meant that the starting point for theological reflection on ecumenism begins not with doctrine but with praxis, particularly as it relates to the common believer in the pew. The ecclesiological model “Body of Christ” provides a helpful vocabulary in this exploration for a number of reasons, none the least that it is scripturally-based, presumes diversity and employs concrete imagery relating to everyday life. Further, “Body of Christ” language is used by numerous Christian denominations in their statements of self-identity, regardless of where they lie on the doctrinal or political spectrum. In this article, potential benefits and challenges of this ground-up perspective will be considered, and a way forward will be proposed to promote ecumenical unity across denomination borders. Keywords: ecumenism; ecumenical; ecclesiology; ekklesia; body of Christ; Christianity; denomination; unity-in-diversity; bilateral dialogue; ressourcement; aggiornamento 1. -

The Ecumenism of St. Francis De Sales

STUDIES IN SALESIAN SPIRITUALITY RUTH KLEINMAN The Ecumenism of St. Francis de Sales originally published in Salesian Studies 5/2 (Spring 1968): 42-49 In connection with the present ecumenical movement Saint Francis de Sales in some ways seems an incongruous figure. True, he had the principal charge of a mission to convert an entire province of his native Savoy, and his later biographers have claimed that he was a forerunner of modern missionaries, relying on none but spiritual weapons to move consciences. He also took a great interest in various projects to re-introduce Catholicism into Geneva, and at one point in his life set down what he believed to be a feasible scheme for the general reconciliation of the Protestant churches with Rome. Yet the historian cannot help noting that the saint shared the attitudes of his time concerning the nature of reunion among the churches and the intervention of the state in the process of conversion. These attitudes are no longer comprehensible to many of our own contemporaries, based as they were on conditions and responses three hundred years removed from us. The form of the Reformation Francis de Sales knew best was Calvinism, as he met it in Geneva and the surrounding provinces of France and Savoy. With Lutheranism he seems to have had little if any personal acquaintance, nor did he have anything to say about the Anglican Church. The differences between the Protestant denominations did not concern him greatly. He tended to lump them together, as when he wrote, “We speak indifferently of Luther and Calvin, because we do not believe that their teachings are widely divergent.” As far as he was concerned, Protestantism was heresy, and heresy was rebellion against God, the Church, and usually also the lawful authority of princes.