Orthodoxy and Ecumenism in Eastern Europe Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is Ecumenism*?

What is Ecumenism*? From the Greek meaning “inhabited house.” A worldwide movement among Christians who accept Jesus as Lord and savior and, inspired by the Holy Spirit, seek through prayer, dialogue, and other initiatives to eliminate barriers and move toward the unity Christ willed for his church (Jn 17:21; see also Eph 4:4-5, UR 1-4). Christian communities separated over the Council of Ephesus (431), over the Council of Chalcedon (451), through the East-West schism conventionally dated 1054, at the Reformation in the sixteenth century, and later. Vatican II taught that the true church “subsists in” but is not simply identified with the Catholic Church (LG 8). Belief in Christ and baptism establish a real, if imperfect, union among all Christians (LG 15). In particular, the Orthodox share with Catholics very many elements of faith and sacramental life, including the Eucharist and apostolic succession (see OE 27-30). The Church Unity Octave, eight days of prayer for religious unity of all Christians, which is celebrated each year from January 17 to 25, was stared in 1908 by the founder of the Society of Atonement, Fr. Paul Wattson (1863-1940) when still a member of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States. The following year, with other friars, sisters, and laymen of his Graymoor community, he was received into the Catholic Church * From A Concise Dictionary of Theology. Eds. Gerald O’Collins, S.J. and Edward Farrugia, S.J. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 2000. What is Interreligious Dialogue? First, interreligious dialogue can be described as a kind of “formal conversation” with persons of non- Christian faiths. -

An Ecumenical Journey

An Ecumenical Journey A timeline of the World Council of Churches The Netherlands 1948 Zimbabwe 1998 USA 1954 Canada 1983 Sweden 1968 Australia 1991 India 1961 Kenya 1975 Brazil 2006 General Secretaries of WCC W. A. Visser ’t Hooft (1900-1985) Philip Potter (1921-) Konrad Raiser (1938-) Olav Fykse Tveit (1960-) Term: 1938-1966 Term: 1972-1985 Term: 1993-2003 Term: 2010- A brilliant and visionary Christian leader from the A Methodist pastor, missionary and youth leader from A German theologian who served on the WCC staff under A pastor from the Lutheran communion, Tveit began his Netherlands, Willem Visser ’t Hooft was named WCC general Dominica in the West Indies, Potter was called to several Philip Potter, Raiser once described his ecumenical calling as term of office in January 2010 following seven years as secretary at the 1938 meeting in which the WCC’s process of positions in the WCC. During his mandate as general “a second conversion.” During a sometimes turbulent period leader of the Church of Norway’s council on ecumenical formation began. A Reformed minister, he emphasized the secretary, he insisted on the fundamental unity of Christian for the ecumenical movement, he led the Council as general and international relations. Bringing wide experience in importance of linking the ecumenical movement to enduring witness and Christian service and the correlation of faith secretary in a redefinition of its “Common Understanding inter-religious dialogue, Tveit had also served as co-chair manifestations of the church through the ages. In 1968 he and action. and Vision” and in a fundamental review of the participation of the Palestine Israel Ecumenical Forum core group was elected honorary president of the WCC by the fourth of Orthodox member churches. -

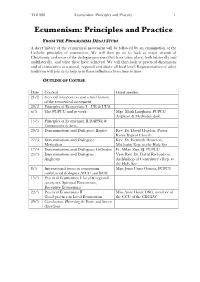

Ecumenism, Principles and Practice

TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 1 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice FROM THE PROGRAMMA DEGLI STUDI A short history of the ecumenical movement will be followed by an examination of the Catholic principles of ecumenism. We will then go on to look at major strands of Christianity and some of the dialogue processes that have taken place, both bilaterally and multilaterally, and what these have achieved. We will then look at practical dimensions and of ecumenism at national, regional and above all local level. Representatives of other traditions will join us to help us in these reflections from time to time. OUTLINE OF COURSE Date Content Guest speaker 21/2 General introduction and a brief history of the ecumenical movement 28/2 Principles of Ecumenism I – UR & UUS 6/3 The PCPCU and its work Mgr. Mark Langham, PCPCU Anglican & Methodist desk. 13/3 Principles of Ecumenism II DAPNE & Communicatio in Sacris 20/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Baptist Rev. Dr. David Hogdon, Pastor, Rome Baptist Church. 27/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Rev. Dr. Kenneth Howcroft, Methodists Methodist Rep. to the Holy See 17/4 Denominations and Dialogues: Orthodox Fr. Milan Zust SJ, PCPCU 24/4 Denominations and Dialogues : Very Rev. Dr. David Richardson, Anglicans Archbishop of Canterbury‘s Rep. to the Holy See 8/5 International issues in ecumenism, Mgr. Juan Usma Gomez, PCPCU multilateral dialogues ,WCC and BEM 15/5 Practical Ecumenism I: local & regional structures, Spiritual Ecumenism, Receptive Ecumenism 22/5 Practical Ecumenism II Miss Anne Doyle DSG, member of Good practice in Local Ecumenism the CCU of the CBCEW 29/5 Conclusion: Harvesting the Fruits and future directions TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 2 Ecumenical Resources CHURCH DOCUMENTS Second Vatican Council Unitatis Redentigratio (1964) PCPCU Directory for the Application of the Principles and Norms of Ecumenism (1993) Pope John Paul II Ut Unum Sint. -

A Report of the House of Bishops' Working Party on Women in the Episcopate Church Ho

Women Bishops in the Church of England? A report of the House of Bishops’ Working Party on Women in the Episcopate Church House Publishing Church House Great Smith Street London SW1P 3NZ Tel: 020 7898 1451 Fax: 020 7989 1449 ISBN 0 7151 4037 X GS 1557 Printed in England by The Cromwell Press Ltd, Trowbridge, Wiltshire Published 2004 for the House of Bishops of the General Synod of the Church of England by Church House Publishing. Copyright © The Archbishops’ Council 2004 Index copyright © Meg Davies 2004 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or stored or transmitted by any means or in any form, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system without written permission, which should be sought from the Copyright Administrator, The Archbishops’ Council, Church of England, Church House, Great Smith Street, London SW1P 3NZ. Email: [email protected]. The Scripture quotations contained herein are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright © 1989, by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA, and are used by permission. All rights reserved. Contents Membership of the Working Party vii Prefaceix Foreword by the Chair of the Working Party xi 1. Introduction 1 2. Episcopacy in the Church of England 8 3. How should we approach the issue of whether women 66 should be ordained as bishops? 4. The development of women’s ministry 114 in the Church of England 5. Can it be right in principle for women to be consecrated as 136 bishops in the Church of England? 6. -

Index to the Papers Presented to Parliament

Index to the Papers Presented to Parliament SESSION 1978-79-80 Presented Printed Journals V. & P. Paper Paper Page Page Year No. Aboriginal Affairs. See "Department of" Aboriginal Affairs-House of Representatives Standing Committee- Government response to Report on- Alcohol problems of Aboriginals . 977 Reports- Aboriginal health-Report, dated 20 March 1979, together with transcript of evidence and copies of extracts of minutes of proceedings of committee . 677 1979 60* Aboriginal legal aid-Report, dated July 1980, incorporating a dissenting report, together with transcript of evidence and extracts from minutes of proceeding of com m ittee . 1588 1980 149* Aboriginal communities in Northern Territory- Impact of mining royalties-Ist Report to Minister for Aboriginal Affairs by Shann Turnbull, Director, Management and Investment Limited, 27 October 1977 . 167 230 1978 135 Self-sufficiency (with land rights)-2nd Report to Minister for Aboriginal Affairs by Shann Turnbull, Director, Management and Investment Limited, 9 June 1978 . 489 572 1978 438 And see "Social impact of uranium mining, etc." Aboriginal Councils and Associations Act-Regulations-Statutory Rules-1978- N o. 137 . .. 289 334 Aboriginal Development Agency-Ministerial statement, 26 October 1978 . 498 Aboriginal health. See "Aboriginal Affairs" Aboriginal Hostels Limited-Report and Financial statement-Period- 27 June 1976 to 25 June 1977 (3rd) . 32 28 1978 56 26 June 1977 to 24 June 1978 (4th) . 508 592 1978 355 25 June 1978 to 30 June 1979 (5th) . 1048 1191 1979 340 Aboriginal Land Commissioner. See- "Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act", "Alyawarra and Kaititja land claim", "Anmatijirra and Alyawarra land claim", "Borroloola land claim", "Uluru (Ayers Rock), etc.", "Warlpiri and Kartangarurru-Kurinintji land claim", and "Yingawunarri (Old Top Springs) Mudubura land claim" Aboriginal Land Fund Act-Aboriginal Land Fund Commission-Report and financial statements, together with Auditor-General's Report-Year- 1976-77 (3rd) . -

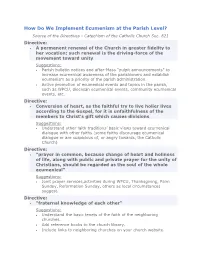

How Do We Implement Ecumenism at the Parish Level? Source of the Directives - Catechism of the Catholic Church Sec

How Do We Implement Ecumenism at the Parish Level? Source of the Directives - Catechism of the Catholic Church Sec. 821 Directive: A permanent renewal of the Church in greater fidelity to her vocation; such renewal is the driving-force of the movement toward unity Suggestions: Parish bulletin notices and after-Mass "pulpit announcements" to increase ecumenical awareness of the parishioners and establish ecumenism as a priority of the parish administration. Active promotion of ecumenical events and topics in the parish, such as WPCU, diocesan ecumenical events, community ecumenical events, etc. Directive: Conversion of heart, as the faithful try to live holier lives according to the Gospel, for it is unfaithfulness of the members to Christ's gift which causes divisions Suggestions: Understand other faith traditions’ basic views toward ecumenical dialogue with other faiths (some faiths discourage ecumenical dialogue or are suspicious of, or angry towards, the Catholic Church) Directive: "prayer in common, because change of heart and holiness of life, along with public and private prayer for the unity of Christians, should be regarded as the soul of the whole ecumenical" Suggestions: Joint prayer services,activities during WPCU, Thanksgiving, Palm Sunday, Reformation Sunday, others as local circumstances suggest. Directive: "fraternal knowledge of each other" Suggestions: Understand the basic tenets of the faith of the neighboring churches. Add reference books to the church library. Include links to neighboring churches on your church website. Directive: "ecumenical formation, of the faithful and especially of priests" Suggestions: For larger parishes, form an ecumenical and interreligious commission. For smaller parishes, appoint an appropriate person as the ecumenical & interfaith liaison. -

118102 JAN. 2009 WORD.Indd

Volume 53 No. 1 January 2009 VOLUME 53 NO. 1 JANUARY 2009 contents COVER THEOPHANY: The Baptism of Christ 3 EDITORIAL by Rt. Rev. John Abdalah 4 CANON 28 OF THE 4TH ECUMENICAL COUNCIL by Metropolitan PHILIP 10 METROPOLITAN PHILIP HOSTS ANTIOCHIAN SEMINARIANS IN ANNUAL EVENT 14 FR. FRED PFEIL INTERVIEWS FR. DAVID ALEXANDER, The Most Reverend US NAVY CHAPLAIN Metropolitan PHILIP, D.H.L., D.D. Primate 17 DEPARTMENT OF YOUTH MINISTRIES The Right Reverend Bishop ANTOUN 21 ORATORICAL FESTIVAL The Right Reverend Bishop JOSEPH The Right Reverend 23 COMMUNITIES IN ACTION Bishop BASIL The Right Reverend 31 ORTHODOX WORLD Bishop THOMAS The Right Reverend 35 THE PEOPLE SPEAK … Bishop MARK The Right Reverend Bishop ALEXANDER Icons courtesy of Come and See Icons. Founded in Arabic as www.comeandseeicons.com Al Kalimat in 1905 by Saint Raphael (Hawaweeny) Founded in English as The WORD in 1957 by Metropolitan ANTONY (Bashir) Editor in Chief The Rt. Rev. John P. Abdalah, D.Min. Assistant Editor Christopher Humphrey, Ph.D. Editorial Board The Very Rev. Joseph J. Allen, Th.D. Anthony Bashir, Ph.D. The Very Rev. Antony Gabriel, Th.M. The Very Rev. Peter Gillquist Letters to the editor are welcome and should include the author’s full name and Ronald Nicola parish. Submissions for “Communities in Action” must be approved by the local Najib E. Saliba, Ph.D. pastor. Both may be edited for purposes of clarity and space. All submissions, in The Very Rev. Paul Schneirla, M.Div. hard copy, on disk or e-mailed, should be double-spaced for editing purposes. -

Ekklesia and Ecumenism in the Body of Christ: Unity from the Ground-Up

religions Article Ekklesia and Ecumenism in the Body of Christ: Unity from the Ground-Up Anastasia Wendlinder Gonzaga University, 502 East Boone Avenue, Spokane, WA 99258-0102, USA; [email protected] Received: 9 October 2018; Accepted: 22 November 2018; Published: 28 November 2018 Abstract: This article explores the implications for Christian unity from the perspective of the lived faith community, the ekklesia. While bilateral and multilateral dialogues have borne great fruit in bringing Christian denominations closer together, as indeed it will continue to do so, considering how the ecclesiological identity of the faith community both forms and reflects its members may be helpful in moving forward in our ecumenical efforts. This calls for a ground-up approach as opposed to a top-down approach. By “ground-up” it is meant that the starting point for theological reflection on ecumenism begins not with doctrine but with praxis, particularly as it relates to the common believer in the pew. The ecclesiological model “Body of Christ” provides a helpful vocabulary in this exploration for a number of reasons, none the least that it is scripturally-based, presumes diversity and employs concrete imagery relating to everyday life. Further, “Body of Christ” language is used by numerous Christian denominations in their statements of self-identity, regardless of where they lie on the doctrinal or political spectrum. In this article, potential benefits and challenges of this ground-up perspective will be considered, and a way forward will be proposed to promote ecumenical unity across denomination borders. Keywords: ecumenism; ecumenical; ecclesiology; ekklesia; body of Christ; Christianity; denomination; unity-in-diversity; bilateral dialogue; ressourcement; aggiornamento 1. -

The Ecumenism of St. Francis De Sales

STUDIES IN SALESIAN SPIRITUALITY RUTH KLEINMAN The Ecumenism of St. Francis de Sales originally published in Salesian Studies 5/2 (Spring 1968): 42-49 In connection with the present ecumenical movement Saint Francis de Sales in some ways seems an incongruous figure. True, he had the principal charge of a mission to convert an entire province of his native Savoy, and his later biographers have claimed that he was a forerunner of modern missionaries, relying on none but spiritual weapons to move consciences. He also took a great interest in various projects to re-introduce Catholicism into Geneva, and at one point in his life set down what he believed to be a feasible scheme for the general reconciliation of the Protestant churches with Rome. Yet the historian cannot help noting that the saint shared the attitudes of his time concerning the nature of reunion among the churches and the intervention of the state in the process of conversion. These attitudes are no longer comprehensible to many of our own contemporaries, based as they were on conditions and responses three hundred years removed from us. The form of the Reformation Francis de Sales knew best was Calvinism, as he met it in Geneva and the surrounding provinces of France and Savoy. With Lutheranism he seems to have had little if any personal acquaintance, nor did he have anything to say about the Anglican Church. The differences between the Protestant denominations did not concern him greatly. He tended to lump them together, as when he wrote, “We speak indifferently of Luther and Calvin, because we do not believe that their teachings are widely divergent.” As far as he was concerned, Protestantism was heresy, and heresy was rebellion against God, the Church, and usually also the lawful authority of princes. -

Ecumenism in the 21St Century

Ecumenism in the 21st Century Report of the Consultation Convened by the World Council of Churches Chavannes-de-Bogis, Switzerland 30 November to 3 December 2004 World Council of Churches Geneva This is a working document, which has been produced within a tight deadline. It has therefore not been possible to devote time to addi- tional editing, style, etc. © 2005, World Council of Churches 150, route de Ferney, P.O. Box 2100 1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland Web site: http://www.wcc-coe.org Printed in Switzerland Contents 1 Ecumenism in the 21st century: Background to the Consultation 3 Final Statement from the Consultation 12 Summary of Proceedings Appendices 33 I Opening Remarks Presentation by Rev Dr Samuel Kobia 38 II Ecumenism in Process of Transformation Presentation by His Holiness Aram I 46 III Ecumenism and Pentecostals: A Latin American Perspective Presentation by Dr Oscar Corvalán-Vásquez 58 IV Dreams and Visions: Living the Deepening Contradictions of Ecumenism in the 21st Century Presentation by Dr Musimbi Kanyoro 66 V. Mapping the Oikoumene: A Study of Current Ecumenical Structures and Relationships Presentation by Jill Hawkey 81 VI Bible Studies Led by Rev Wesley Ariarajah 85 VII List of Participants 1 Ecumenism in the 21st Century: Background to the Consultation Over the past 50 years, churches throughout the world have established many different ecumenical organisations at the national, regional and global levels in a quest to discover Christian unity and also to assist the churches to respond to the needs of the world. In recent years, questions have been increasingly raised regarding the relationships between these various organi- sations their financial sustainability and whether a reconfiguration of ecu- menical life is necessary in order to meet the challenges of the 21st century. -

Essays in Orthodox Ecclesiology

ESSAYS IN ORTHODOX ECCLESIOLOGY Vladimir Moss © Copyright: Vladimir Moss, 2014. All Rights Reserved. 1 INTRODUCTION 4 1. THE CHURCH AS THE BRIDE OF CHRIST 5 2. DO HERETICS HAVE THE GRACE OF SACRAMENTS? 20 3. THE BRANCH AND MONOLITH THEORIES OF THE CHURCH 42 4. THE ECUMENICAL PATRIARCHATE AND THE NEW WORLD ORDER 52 5. THE CYPRIANITES, THE TIKHONITES AND BISHOP AGATHANGELUS 58 6. WHAT IS THE LOCAL CHURCH? 62 7. THE HERESY OF ECCLESIASTICAL ELITISM 76 8. ON THE CONDEMNATION OF HERETICS 80 9. THE CESSATION OF DIALOGUE 94 10. THE LIMITS OF THE CHURCH: A REVIEW OF THE ARGUMENT 97 11. “THERE IS NONE THAT WATCHETH OUT FOR MY SOUL” 106 12. PATRISTIC TESTIMONIES ON THE BODY AND BLOOD OF CHRIST 112 13. SCRIPTURAL AND PATRISTIC TESTIMONIES ON THE NECESSITY OF HAVING NO COMMUNION WITH HERETICS AND SCHISMATICS 122 14. KHOMIAKOV ON SOBORNOST’ 125 15. THE ABRAHAMIC COVENANT 130 16. THE UNITY OF THE TRUE ORTHODOX CHURCH 145 17. ON NOT ROCKING THE BOAT 160 18. ORTHODOXY, UNIVERSALISM AND NATIONALISM 169 19. IN DEFENCE OF THE TRUE ORTHODOX CHURCH OF GREECE 187 20. THE POWER OF ANATHEMA 193 21. THE APOSTOLIC SUCCESSION OF THE ROMANIAN OLD CALENDARIST CHURCHES 210 22. IS THE SERBIAN TRUE ORTHODOX CHURCH SCHISMATIC? 219 23. TOWARDS THE EIGHTH ECUMENICAL COUNCIL 243 24. THE KALLINIKITE UNIA 250 25. TOWARDS THE “MAJOR SYNOD” OF THE TRUE ORTHODOX CHURCH 262 2 26. THE KALLINIKITE UNIA – CONTINUED 271 3 INTRODUCTION This book collects into one place various articles on ecclesiological themes that I have written in the last fifteen years or so. -

Medical-Ethics Commission

Church Ministries / Commissions Medical/Ethics Commission Chairperson V. Rev. John Breck Commission Email [email protected] 6102 Rockefeller Rd. Wadmalaw Island, SC 29487 Commission Web www.oca.org /DOdept.asp?SID=5&LID=19 Home 843-559-1404 Email [email protected] Members Dr. Al Calabrese V. Rev. Michael Matsko Rev. Paul Minkowski Dr. Nicola Nicoloff Juliana Orr-Weaver Dr. Al Rossi Dr. John Shultz Rev. Dn. Michael Wusylko Accomplishments/Progress Since the 13th All-American Council The Medical-Ethics Commission keeps abreast of the latest developments in medical science, bioethics, and related fields on behalf of and in an effort to advise the Holy Synod of Bishops. The commission also provides resources and recommendations on contemporary medical and ethical issues as needs arise. The last report of this commission was submitted in July 2004. During that year I was in discussion with Dr. Al Rossi regarding his SCOBA paper on homosexuality and same-sex unions, and with Dr. Terry Orr-Weaver on the question of the status of the pre-implantation embryo. These are areas of primary importance for us today, given the current pres- sures in this country toward legalizing same-sex marriage, and toward acceptance of medical procedures involving manipulation of human embryos, including human cloning. There is a great deal of discussion currently going on in both of these areas, and it is not yet possible to provide answers to some of the most pressing issues. With regard to same-sex unions: Dr. Rossi drafted a very thoughtful paper on homosexuality in response to a SCOBA request for a statement that addresses the problem of same-sex unions.