10-224 National Meat Assn. V. Harris (01/23/2012)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Variocookingcenter Application Manual Foreword

® VarioCookingCenter Application Manual Foreword Dear User, ® With your decision to purchase a VarioCookingCenter , you have made the right choice. ® The VarioCookingCenter will not only reliably assist you with routine tasks such as checking and adjusting, it also provides you with cooking experience of cooking, pan-frying and deep- frying gathered over years – all at the push of a button. You choose the product you would ® like to prepare and select the result you would like from the VarioCookingCenter – and then you have time for the essentials again. ® The VarioCookingCenter automatically detects the load size and the size of the products, and controls the temperatures according to your wishes. Permanent supervision of the ® cooking process is no longer necessary. Your VarioCookingCenter gives you a signal when your desired result is ready or when you have to turn or load the food. This Application Manual has been designed to give you ideas and help you to use your ® VarioCookingCenter . The contents have been classified according to meat, fish, side dishes and vegetables, egg dishes, soups and sauces, dairy products and desserts as ® well as Finishing . At the beginning of each chapter there is an overview showing the cooking processes contained with recommendations as to which products can ideally be prepared using which process. In addition, each section provides useful tips on how to use the accessories. ® As an active VarioCookingCenter user we would like to invite you to attend a day seminar at our ConnectedCooking.com. In a relaxed atmosphere, you can experience how you can ® make the best and most efficient use of the VarioCookingCenter in your kitchen. -

Wilderness Cookery, by Bradford Angier ______• Cooking the One Burner Way, by Melissa Gray and Buck Tilton, Globe Pequot

meat to the pot after the vegetarian portions are prepared (i.e. the spaghetti MAIL-IN CARD FOR FOOD SUBSTITUTIONS meal would require pulling out the noodles and tomato sauce for the AsMAIL-IN a crew, we understand CARD if FORwe wish FOOD to request SUBSTITUTIONS food substitutions for vegetarian before adding the MRE pouch with the meat for every one else). Asmedical a crew, reasons, we understand religious if beliefs we wish or tovegetarian request foodneeds, substitutions a letter needs for to In other cases, meal substitutions can be packed in place of the regular medicalbe written reasons, to Northern religious Tier beliefs, explaining or vegetarian the circumstances. needs, a Thisletter card needs is for to meal. becrews written to torequest the Northern food substitutions Tier explaining for other the circumstances.reasons. This card is This book was prepared for you. for crews to request food substitutions for other reasons. WILDERNESS The following is a list of most of the vegetarian items we will be stocking in This card needs to be mailed to the Northern Tier only if we are requesting Please read it thoroughly the commissary this summer. These items are in addition to items like rice, Thisa food card substitution. needs to be It mailed must be to receivedthe Northern no later Tier than only 3 ifweeks we are prior re- to the pasta, egg noodles, and dry sliced potatoes. questingstart of ayour food trip. substitution. Any substitutions It must listedbe received on this nocard later pertain than to May only 15. the and if you have any questions, COOKERY Anycrew substitutions listed. -

Uncovering Secrets of the "Fish of 10,000 Casts": the Physiological Ecology And

Uncovering Secrets of the "Fish of 10,000 Casts": The Physiological Ecology and Behaviour of Muskellunge (Esox masquinongy) By Sean Joseph Landsman B.Sc., University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2009 A thesis submitted to The Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Ottawa Carleton Institute of Biology Carleton, University Ottawa, Ontario, Canada ©2011, Sean Joseph Landsman Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-87852-1 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-87852-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Taste the CKC Good Food Difference

Taste the CKC Good Food Difference With more than 25 years of catering experience, CKC can provide food to impress any crowd large or small and take the stress off you. From formal affairs to casual picnics and barbecues, CKC Good Food provides premium service and a variety of delicious menus to fit your needs and budget. Whether your event is for 50 or 5,000 people, make it truly special with CKC Good Food catering! MTCS has been using CKC catering for more than 15 years - they are always our first go-to for our catering needs! We have enjoyed every bite of the professional experience. Erin Schurman Executive Assistant To Superintendent Minnesota Transitions Charter School Catering menus Breakfast Beverages Lunch Buffets & Boxes Holiday Special Events Buffet & Plated Dinners School Fundraisers / Galas Sweet & Savory Dessert Graduation Parties Our standard menus give you a glimpse into Chef Naj’s culinary depth and versatility. These menus are just the beginning. Have something specific you want? We often develop custom menus for specific themes and tastes and would love to discuss your vision for your event. Your satisfaction is our highest goal. Call us today to taste the CKC Good Food difference. 651.453.1136 | CKCGoodFood.com © CKC Good Food Dinner Appetizers Minimum 10 persons (each appetizer order, 3 bites per person) Cream Cheese Won Ton with Sweet & Sour Sauce $3 per person Spanakopita $3 per person Flaky Filo Dough Stuffed with Spinach & Cheese Served with Tzatziki Sauce Hummus & Pita Chips or Pita Bread $3 per person Choice of -

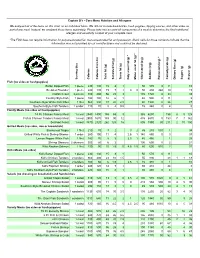

Nutritional and Allergen Information

Captain D's - Core Menu Nutrition and Allergens We analyzed all of the items on this chart on an individual basis. We did not include breadsticks, hush puppies, dipping sauces, and other sides as part of any meal. Instead, we analyzed those items separately. Please take into account all components of a meal to determine the final nutritional, allergen and sensitivity content of your complete meal. *The FDA does not require information for polyunsaturated fat, monounsaturated fat and potassium. Blank cells for those nutrients indicate that the information was not provided by our manufacturers and could not be declared. Serving Size Serving Calories Calories from fat Total fat (g) fatSaturated (g) fat Trans (g) fatunsat Poly (g) * fat (g)Mono unsat * (mg)Cholesterol Sodium (mg) (mg) Potassium * (g) Carbohydrate Dietary fiber (g) (g) Sugars Protein (g) Fish (no sides or hushpuppies) Batter Dipped Fish 1 piece 230 130 15 8 1 50 570 0 11 10 Breaded Flounder 1 piece 240 130 15 7 1 0 0 50 430 260 10 15 Catfish Feast 3 pieces 780 490 56 25 3 185 1720 0 33 33 Country-Style Fish 1 piece 190 100 12 6 1 40 500 0 11 9 Southern-Style White Fish Fillet 1 filet 560 330 37 20 2.5 80 1390 0 26 27 Southern-Style Fish Tenders 1 tender 110 70 8 4 0.5 15 240 0 4 5 Family Meals (no sides or hushpuppies) 14 Pc Chicken Family Meal 1 meal 2540 1400 158 69 9 385 6250 158 8 8 125 Fish & Chicken Tenders Family Meal 1 meal 2900 1670 189 90 12 435 6870 0 153 7 7 142 Seafood Feast 1 meal 3870 2320 262 125 16 805 7990 90 211 2 10 150 Grilled Meals (no sides, rice or -

The Catering Menu

Catering 3325 Newport Blvd. Newport Beach, Ca. 92663 949‐675 6990 / www.pescadoubistro.com ENTREES (Minimum of 20 people per selection) served in large aluminum to go containers for pick up price per person + 7.75% tax For parties catered with service add 18% for prep. and delivery. Servers extra All entrees include a salad : Mesclun greens with vinaigrette Poultry Coq au Vin 14.50 Chicken marinated in red wine, served in its natural juices with mushroom, carrots, peas, pearl onions and mashed potatoes. Poulet a lʹestragon 14.50 Braised chicken in white wine, chicken stock and fresh tarragon, mushroom, Dijon mustard and cream, mashed potatoes. Poulet Provencal 14.50 Sautéed chicken in olive oil, garlic, plum tomatoes, zucchinis, eggplant and black olives, bow tie pasta. Supreme de poulet au Miel 16.50 Braised boneless breast of chicken with sage, thyme, honey and chicken broth, roasted fennel and mashed potatoes Supreme de poulet Florentine 16.50 Chicken breast stuffed with spinach leaves and Swiss cheese, slow baked in mushroom veloute sauce, mashed potatoes. Canard a lʹorange 17.50 Roasted breast of duck, orange‐triple sec sauce, sauteed zucchinis and mashed potatoes Bon Appetit Meat Boeuf Bourguignon 17.50 Braised beef stew in red wine, aromatic vegetables, carrots, mushroom, pearl onions and mashed potatoes Boeuf braise aux petits legumes 17.50 Braised beef shank in white wine and stock, carrots, celery, onion, tomato and potatoes Roti de boeuf au poivre 19.50 Roasted boneless beef rib loin, green peppercorn sauce, sauteed green beans -

01 Methods of Cooking

Food Production Foundation -II BHM -201T UNIT: 01 METHODS OF COOKING Structure 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Objectives 1.3 Heat and Cooking 1.3.1 What is heat? 1.3.2 Effect of Heat on food 1.3.3 Method of heat transfer 1.4 Methods of cooking 1.5 Moist heat Methods of Cooking 1.5.1 Boiling 1.5.2 Poaching 1.5.3 Steaming 1.5.4 Stewing 1.5.5 Braising 1.6 Dry heat Methods of Cooking 1.6.1 Baking 1.6.2 Roasting 1.6.3 Grilling 1.7 Frying 1.8 Modern Methods of cooking 1.8.1 Paper Bag (en papillotte) 1.8.2 Microwave Cooking 1.8.3 Infra-red Cooking 1.9 HACCP Standards and Professional Kitchens 1.9.1 Introduction 1.9.2 What is HACCP? 1.9.3 Food Preparation Hazard and Control Rules 1.10 Summary 1.11 Key Terms 1.12 References and Bibliography 1.13 Review Questions 1.1 Introduction This chapter deals with basic principles. You will learn about what happens to food when it is heated, about how food is cooked by different methods, and about rules of seasoning and flavouring. It is important to understand the science of food and cooking so you can successfully use these principles in the kitchen. 1.2 Objectives After reading this unit the learner will be able to understand: • Methods of heat transfer Uttarakhand Open University 1 Food Production Foundation -II BHM -201T • Effect of heat on food • Moist heat Methods of Cooking • Dry heat Methods of Cooking • Frying • Modern Methods of cooking 1.3 Heat and Cooking To cook food means to heat it in order to make certain changes in it. -

Pico De Gallo (Lg).……

Cheese Quesadilla (Corn or Flour)………..........................................................MEAT $1.80 QUESADILLA Steak or Lengua Quesadilla................................................................................$2.70 Meat Quesadilla (Chorizo, Chicken, Beef or Pastor)…….................................$2.20 Hamburger……….................................................................................................$2.45 Cheeseburger……….........................................................……............................$2.95 Combo Meal (Burger fry & medium pop)…….........................................……...$5.25 Combo Meal with Cheese………….....................................................................CHEESE BURGER $5.60 Ketchup, Mayonnaise, Lettuce and Tomato Cheese………………....................$0.55 Avocado on King Burrito...…….$1.30 Rice on Burrito………………......$0.55 Avocado on Jr. Burrito.......…….$0.85 Small Guacamole….....………….$1.70 Avocado on Taco.................……$0.65 Large Guacamole….....………….$2.95 Avocado on Torta................…….$0.85 Cheese Sauce Small….....…..….$1.20 Jalapeño (8 oz)....................…….$1.00 Cheese Sauce Large.............…..$2.00 Jalapeño (16 oz)........…......…….$2.00 Sour Cream…………............…....$0.55 Chile Torreados (each) ......…….$0.35 Pico de Gallo (Lg).……................$1.50 Flan………...........................…….$2.60 Pico de Gallo (SM)……................$0.75 Beans………….............................$1.35 Cheese Fries…….............……….$2.70 Sour Cream…...........................…$0.55 -

CB Butcher Box

CB Butcher Box Barbecue season is officially over. We stretched it as long as we could, but it’s time to cover up the grill for a few months, and we at Charlies Burgers have a new Butcher Box for all your indoor cooking needs. The centerpiece here is Osso Buco, or cross-cut veal shank. It is one of the most deeply flavoured and complex cuts of veal, famous for its Milanese incarnation, which we have included a simple recipe for below. The Osso Buco and the Chicken Supreme are both great braising meats, and we have also included some perfect filet mignon meant for simple pan cooking, along with a giant ribeye roast that works best seared and then slow cooked. All of these cuts are designed for the type of hearty, comfort cooking that we all need right now, and all are perfect accompaniments to the many wines we have available for delivery. Enjoy! The Meat: Wine Suggestions: • 2x Provimi Osso Buco Centre Cut 1.5” thick, 14oz each. This is one of the most flavourful cuts of meat out there, ideal for hearty winter meals: While we aren’t sending any specific wine • To cook classic Osso Buco, first cut little slits into the meat pairings with this package, we would love and stuff with a mix of chopped garlic, sage and rosemary to help you find the perfect wine for these (trito) before refrigerating for an hour. Next, preheat your cuts, and have included some suggestions oven to 325F and sear the meat in a heavy bottomed pot from our wine store. -

Dinner Menu Bahnschrift- 10.15.18.Docx

STARTERS CHERRY FOIE GRAS 20 Unique presentation of decadent Foie Gras Mousse dipped in a cherry glaze served chilled CHINESE CHAYOTE 12 Savory Chayote squash marinated in soy, garlic, red pepper w. hint of sweetness TEA SMOKED CHICKEN 13 House smoked w. delicate flavor of Chinese tea leaves, soy, & ginger ROASTED PORK 12 Slow roasted pork till crispy outside and tending inside coated with sweet tangy BBQ TEA SMOKED SALMON 15 Salmon smoked w. flavor of Chinese tea leaves, soy, ginger that gives it a light crispness TENDER VEAL 16 Slow cooked veal, glazed w. a hint of sweetness, coated w. peanuts, & dried red peppers HANGZHOU LOTUS ROOT 14 Beautiful lotus root filled with sweet rice, honey & has pleasant floral notes of apricot & peach JIANGNAN CHINESE SALAD 13 Vibrant salad made with cabbage, carrots, apple, cilantro, orange zest, & topped w. sweet potato crisp SEAFOOD MIX 22 Shrimp, crab, scallop, clam, & julienne cucumber served in tower glass w. our soy-chili sauce HOMEMADE PORK & BEEF DUMPLINGS 12 Pan fried to golden brown yet soft and flavorful w. our house made soy & vinegar sauce CHINESE YAM 14 Great to start or end your meal. Chinese yams topped w. blueberry glaze and honey citrus create a delicate yam that is a Chinese specialty to provide health and wellbeing SHRIMP SPRING ROLLS 2 for 6 / 5 for 12 Shrimp, onion, carrots, mushrooms, & cabbage fried till golden brown w. our sweet chili sauce DUCK SPRING ROLLS 2 for 6 / 5 for 12 Duck, onion, carrots, mushrooms, & cabbage fried till golden brown w. our sweet chili sauce VEGETABLE ROLLS 2 for 5 / 5 for 12 Carrots, onion, mushrooms & cabbage fried till golden brown w. -

Republic of France As Amicus Curiae in Support of Petitioners

No. 17-1285 ================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- --------------------------------- ASSOCIATION DES ÉLEVEURS DE CANARDS ET D’OIES DU QUÉBEC; HVFG LLC; AND HOT’S RESTAURANT GROUP, INC., Petitioners, v. XAVIER BECERRA, IN HIS OFFICIAL CAPACITY AS ATTORNEY GENERAL OF CALIFORNIA, Respondent. --------------------------------- --------------------------------- On Petition For A Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Ninth Circuit --------------------------------- --------------------------------- BRIEF OF THE REPUBLIC OF FRANCE AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS --------------------------------- --------------------------------- LAWRENCE S. EBNER Counsel of Record CAPITAL APPELLATE ADVOCACY PLLC 1701 Pennsylvania Ave., NW Washington, DC 20006 (202) 729-6337 [email protected] Counsel for Amicus Curiae ================================================================ i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTEREST OF THE AMICUS CURIAE ................ 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ................................. 4 ARGUMENT ............................................................ 5 The Court should grant review because the Ninth Circuit’s flawed preemption analysis undermines USDA’s nationally uniform standards for poultry product ingredients ............. 5 A. The PPIA’s express preemption provision mandates national uniformity of poultry product ingredients .......................................... 5 -

Supreme Court of the United States ______

NO. 19-1039 In the Supreme Court of the United States ________________ PENNEAST PIPELINE COMPANY, LLC, Petitioner, v. STATE OF NEW JERSEY, et al., Respondents. ________________ On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit ________________ JOINT APPENDIX Volume I of II ________________ JEREMY M. FEIGENBAUM PAUL D. CLEMENT Counsel of Record Counsel of Record OFFICE OF THE NEW KIRKLAND & ELLIS LLP JERSEY ATTORNEY 1301 Pennsylvania Ave., NW GENERAL Washington, DC 20004 25 Market Street (202) 389-5000 Trenton, NJ 08611 [email protected] (609) 376-2690 [email protected] Counsel for Respondents Counsel for Petitioner State of New Jersey, et al. (Additional Counsel Listed on Inside Cover) March 1, 2021 Petition for Writ of Certiorari Filed Feb. 18, 2020 Petition for Writ of Certiorari Granted Feb. 3, 2021 MATTHEW LITTLETON Counsel of Record DONAHUE, GOLDBERG, WEAVER & LITTLETON 1008 Pennsylvania Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20003 (202) 683-6895 [email protected] JENNIFER L. DANIS EDWARD LLOYD MORNINGSIDE HEIGHTS LEGAL SERVICES 435 W. 116th Street New York, NY 10027 (201) 306-3382 [email protected] [email protected] Counsel for Respondent New Jersey Conservation Foundation JA i TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume I Relevant Docket Entries, United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit, In re: PennEast Pipeline Co., LLC, No. 19-1191 ..................... JA-1 Relevant Docket Entries, United States District Court for the District of New Jersey, In re: PennEast Pipeline Co., LLC, No. 3:18-cv-01597 ........................................ JA-26 Order Issuing Certificates, PennEast Pipeline Co., LLC, 162 FERC ¶ 61,053 (Jan.