The Legacy of Utopian Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus Staatliches Bauhaus, commonly known simply as Bauhaus, was a school in Germany that combined crafts and the fine arts, and was famous for the approach to design that it publicized and taught. It operated from 1919 to 1933. At that time the German term Bauhaus, literally "house of construction" stood for "School of Building". The Bauhaus school was founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar. In spite of its name, and the fact that its founder was an architect, the Bauhaus did not have an architecture department during the first years of its existence. Nonetheless it was founded with the idea of creating a The Bauhaus Dessau 'total' work of art in which all arts, including architecture would eventually be brought together. The Bauhaus style became one of the most influential currents in Modernist architecture and modern design.[1] The Bauhaus had a profound influence upon subsequent developments in art, architecture, graphic design, interior design, industrial design, and typography. The school existed in three German cities (Weimar from 1919 to 1925, Dessau from 1925 to 1932 and Berlin from 1932 to 1933), under three different architect-directors: Walter Gropius from 1919 to 1928, 1921/2, Walter Gropius's Expressionist Hannes Meyer from 1928 to 1930 and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Monument to the March Dead from 1930 until 1933, when the school was closed by its own leadership under pressure from the Nazi regime. The changes of venue and leadership resulted in a constant shifting of focus, technique, instructors, and politics. For instance: the pottery shop was discontinued when the school moved from Weimar to Dessau, even though it had been an important revenue source; when Mies van der Rohe took over the school in 1930, he transformed it into a private school, and would not allow any supporters of Hannes Meyer to attend it. -

The De Stijl Movement in the Netherlands and Related Aspects of Dutch Architecture 1917-1930

25 March 2002 Art History W36456 The De Stijl Movement in the Netherlands and related aspects of Dutch architecture 1917-1930. Walter Gropius, Design for Director’s Office in Weimar Bauhaus, 1923 Walter Gropius, Bauhaus Building, Dessau 1925-26 [Cubism and Architecture: Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Maison Cubiste exhibited at the Salon d’Automne, Paris 1912 Czech Cubism centered around the work of Josef Gocar and Josef Chocol in Prague, notably Gocar’s House of the Black Virgin, Prague and Apt. Building at Prague both of 1913] H.P. (Hendrik Petrus) Berlage Beurs (Stock Exchange), Amsterdam 1897-1903 Diamond Workers Union Building, Amsterdam 1899-1900 J.M. van der Mey, Michel de Klerk and P.L. Kramer’s work on the Sheepvaarthuis, Amsterdam 1911-16. Amsterdam School and in particular the project of social housing at Amsterdam South as well as other isolated housing estates in the expansion of the city. Michel de Klerk (Eigenhaard Development 1914-18; and Piet Kramer (De Dageraad c. 1920) chief proponents of a brick architecture sometimes called Expressionist Robert van t’Hoff, Villa ‘Huis ten Bosch at Huis ter Heide, 1915-16 De Stijl group formed in 1917: Piet Mondrian, Theo van Doesburg, Gerritt Rietveld and others (Van der Leck, Huzar, Oud, Jan Wils, Van t’Hoff) De Stijl (magazine) published 1917-31 and edited by Theo van Doesburg Piet Mondrian’s development of “Neo-Plasticism” in Painting Van Doesburg’s Sixteen Points to a Plastic Architecture Projects for exhibition at the Léonce Rosenberg Gallery, Paris 1923 (Villa à Plan transformable in collaboration with Cor van Eestern Gerritt Rietveld Red/Blue Chair c. -

Taking a Stand? Debating the Bauhaus and Modernism, Heidelberg: Arthistoricum.Net 2021, P

Damnatio Memoriae. The Case of Mart Stam Simone Hain Hain, Simone, Damnatio Memoriae. The Case of Mart Stam, in: Bärnreuther, Andrea (ed.), Taking a Stand? Debating the Bauhaus and Modernism, Heidelberg: arthistoricum.net 2021, p. 359-573, https://doi.org/10.11588/arthistoricum.843.c11919 361 Simone Hain [ B ] What do we understand by taking a stand regarding architecture and design, and particularly of the Bauhaus and Modernism? architectural historiography As early as 1932, 33-year-old Mart Stam was preoccupied with the of modernism idea that he might be counted as dead as far as architectural his- tory, or rather the «West», was concerned, because for over a year and a half he had failed to provide new material for art history. «We Are Not Working Here with the Intention of Influencing How Art Develops and Making New Material Available to Art History» On August 20th, 1932, he wrote to Sigfried Giedion, the most im- portant art historian for architects: «You will be amazed to receive another little letter from me after I have been dead for a year and a half. Yes, I am immersed in our Russian work, in one of the most [ B ] difficult tasks that will ever exist. I know that we won’t be able to build a lot of flawless buildings here, that we won’t be able to produce wonderful material compositions, that we won’t even be able to implement pure floor plans and apartment types, maybe not even flawless city plans. [...] we are not working here with the intention of influencing how art develops and making new mate- rial available to art history, but rather because we are witnessing societal projects of modernism a great cultural-historical development that is almost unprecedent- reshaping the world ed in its scope and extent [...].»1 Stam describes his activities in Russia ex negativo, knowing full well that in doing so he is violating the well-established rela- tionship between himself and Giedion and all the rules of the game in the industry. -

The Economics of the Cantilever Chair, 1929-1936

Working Papers No. 161/12 Steel, Style and Status: The Economics of the Cantilever Chair, 1929-1936 Tobias Vogelgsang © Tobias Vogelgsang March 2012 Department of Economic History London School of Economics Houghton Street London, WC2A 2AE Tel: +44 (0) 20 7955 7860 Fax: +44 (0) 20 7955 7730 2 Steel, Style and Status : The Economics of the Cantilever Chair, 1929-1936 Tobias Vogelgsang* *Acknowledgements: I thank Max-Stephan Schulze for the advice in developing the idea behind this paper and the support in executing it. Susanne Korn and Bernd Gaydos of Thonet have provided indispensable guidance into Thonet's archive and history. Kornelia Rennert has generously provided access to the archives of the Salzgitter and Mannesmann AG. Finally, I greatly appreciate Séamus MacCnáimhín's editorial support. The usual disclaimer applies. 3 Abstract The cantilever chair is an iconic consumer product of the twentieth century and stands for a modern, progressive lifestyle. It is expensive, often used to furnish exclusive spaces and thereby the opposite of its original artistic vision from the late 1920s. By way of comparing historical prices and wages, this paper establishes that the cantilever chair was never a cheap mass commodity but almost immediately acquired an upmarket status with corresponding prices. This is accounted for by programmatic demands of the creative environment from which the chair originated, through the chair's legal status as artwork, consumer tastes, strategic marketing choices and ultimately institutions. 4 The cantilever chair is a modern classic. It is part of the collections of the Victoria & Albert Museum in London and the MoMA in New York, it furnishes the VIP rooms at Berlin's Olympic Stadium and many other exclusive spaces and it is the subject of exhibitions, monographs, coffee table books and scholarly research. -

Mart Stam Œuvrecatalogus

MART1 STAM STEF JACOBS Supplement bij Mart Stam. Dichter van staal en glas ŒUVRECATALOGUS MART STAM STEF JACOBS Supplement bij Mart Stam. Dichter van staal en glas ŒUVRECATALOGUS MART STAM STEF JACOBS Supplement bij Mart Stam. Dichter van staal en glas ŒUVRECATALOGUS ’Bouwen’ verlangt naast het inzicht in de opgave ook inzicht in de middelen ter oplossing. (...) Dit inzicht zal tot vernieuwing van constructie- systemen en tot toepassing van nog ongebruikte materialen leiden. Uit deze wijze van bouwen ont- staan resultaten die ons tot verbazing en bewon- dering dwingen door hun juistheid. Het zijn zowel de producten ontstaan in de massa productie (fiets, badkuip, gloeilamp, schrijfmachine) als de technische bouwwerken (kruiser, elevator, turbine). Mart Stam, ‘Op zoek naar een ABC van het bouwen’, 1927 VOORWOORD 7 VERANTWOORDING 8 CATALOGUS PURMEREND 1917–1918 11 C AT. 1 – 7 ROTTERDAM 1919–1921 15 CAT. 8–14 BERLIJN 1922–1923 20 CAT. 15–20 ZWITSERLAND 1923–1925 27 CAT. 21–47 PARIJS 1925–1926 57 CAT. 48 PURMEREND 1926 59 CAT. 49 ROTTERDAM 1926–1928 61 CAT. 50–74 FRANKFURT AM MAIN 1928–1930 91 CAT. 75–88 SOVJET-UNIE 1930–1934 107 CAT. 89–93 AMSTERDAM 1935–1948 115 CAT. 94–152 SBZ/DDR 1948–1953 171 CAT. 153–161 AMSTERDAM 1953–1966 180 CAT. 162–185 ZWITSERLAND 1966–1983 206 CAT. 186–200 ZAKENREGISTER 220 PERSONENREGISTER 224 COLOFON 230 INHOUD VOORWOORD Deze volledige oeuvrecatalogus begeleidt het proefschrift, waarop ik in september 2016 ben gepromoveerd: Mart Stam. Dichter van staal en glas. Bij die gelegenheid vertelde ik mijn oppo- nenten meer dan eens, dat zij geen goed beeld van Stams werk hadden omdat zij dit niet konden overzien. -

The Thonet Tubular Steel Furniture – an Invention from the Bauhaus Era

Press Release Frankenberg/Germany, June 2018 The Thonet tubular steel furniture – an invention from the Bauhaus era Today, we take the form and aesthetics of tubular steel furniture for granted. They represent legendary milestones in design history. Art historians and materials scientists have been dealing with the details of the development of this design innovation for a long time. When were each of the particular designs created? How did the first tubular steel furniture designers influence each other? After the end of the First World War, society and politics in Germany were struck by a general crisis, which also shook the foundations of everyday aesthetic forms and provoked changes. In 1919, the first post-war year, not only was the Bauhaus in Weimar established but the National Assembly discussed the Weimar Constitution right next door in the theatre, and the Treaty of Versailles divided society. First influenced by expressionism and the Dutch De Stijl movement, several designers, architects and craftsmen started looking for new technologies and forms in the 1920s. For the first time in furniture making, they began experimenting with tubular steel as a material. The concurrence of several factors contributed to the fame and sustainable success of Thonet’s tubular steel furniture. There was the New Building design movement that developed with manifold tendencies, and the aesthetic-cultural educational institution Bauhaus, which repeatedly changed locations due to political changes and changes in its conceptual strategy resulting from its own development. The Bauhaus is a decisive point of reference, but it was not the birthplace of the new furniture. -

Autonomy-Synthesis

AUTONOMY-SYNTHESIS for contemporary projects – between architectural and urban- The recently initiated, broadly defined debate on urbanism planning practice and its dialectical relationship to the social seems definitively to ignore the social relevance of the labour configuration of time and place can no longer take concrete OASE #75 of the urban planner. With the ad hoc objective of filling an form. From now on, the practice of spatial design will thus observed gap in thinking about form in urban design, this de- unapologetically disintegrate into its separate components bate has re-emphasised the autonomy of the discipline and the – planning, urbanism and architecture – which, on the basis individual artist. The fact that urbanism is drawing on an op- of a kind of closed learning and feedback loop, can each de- tion which emphasises that the social origins of the formal are velop in a unique, idiosyncratic way. This parting of ways at unknowable – and thus deliberately and voluntarily retreats as the level of spatial action systems has, however, made it obvi- far as possible from reality – has its roots not least in the for- ous that no part of current design practice is self-evident any malist approach developed by the postmoderns in the 1970s. longer; even its right to exist is no longer self-evident, accord- In 1979 Carel Weeber, one of the Dutch representatives of ing to Jürgen Habermas.3 Because of the crisis of the multi- 3 this school, pointed out that the discipline of urbanism should and interdisciplinary approach that is the inevitable result of Jürgen Habermas, ‘Het moder ne – een onvoltooid be encouraged to shed the mask of other disciplines, in or- this, and because of the more complex field of urban integra- project’, lecture delivered upon der for it to focus exclusively on designing formal structures tion in which the discipline of urbanism has traditionally op- receiving the Adorno Prize, on an urban scale. -

Marcel Breuer Oder Mart Stam

ThonetCont tubularemporary steelsince 18classics19. Über uns Moderne der Architektur Eine der wichtigsten Stationen in der Geschichte der Moderne in Architektur und Gestaltung ist zweifelsohne das Bauhaus. Walter Gropius hatte für diese 1919 gegründete neuartige Ausbil- dungsinstitution die Vereinigung von Kunst und Technik zu einer Einheit gefordert. 1926 nach Mit dem Wirken des Tischlermeisters Michael Thonet (1796 bis 1871) begann unsere traditions- Dessau umgezogen, wurde an dieser Schule so auch mit dem neuartigen Material Stahlrohr reiche Unternehmensgeschichte. In seinem Werk vollzog sich der Übergang von handwerklicher zu experimentiert – u.a. von Bauhaus-Lehrern wie Marcel Breuer oder Mart Stam. Diese Experimente industrieller Möbelfertigung. Der Durchbruch zur industriellen Fertigung gelang Michael Thonet standen im Zusammenhang mit der aufkommenden Bewegung des Neuen Bauens, die dem moder- 1859 in Wien mit dem Stuhl Nr. 14, dem später so genannten „Wiener Caféhaus-Stuhl“, bei dem nen Menschen neue Architektur und neue Einrichtungen bieten wollte. Durch das Engagement von die neuartige Technologie des Biegens von massivem Buchenholz zum Einsatz kam. Die Arbeits- Thonet seit Ende der 1920er Jahre erhielt das Stahlrohrkonzept eine durchschlagende Wirkung und schritte waren industriell standardisiert – erstmals in der Möbelherstellung fand Arbeitsteilung gelangte zu wachsender Popularität. statt. Überdies war der Stuhl einfach zu zerlegen und Platz sparend zu transportieren. Der Stuhl ebnete uns den Weg zum Weltunternehmen; zahlreiche erfolgreiche Bugholz-Möbel folgten. Die zweite Konstante im Thonet-Programm bilden Stahlrohrmöbel. In den 1930er Jahren war das Unter- nehmen der weltweit größte Produzent dieser neuartigen Möbel, die von berühmten Architekten wie Mart Stam, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe oder Marcel Breuer stammten. Heute gelten die frühen Gestalter am Bauhaus Stahlrohrmöbel als Meilensteine in der Designgeschichte. -

Bargstadt Disruption in Germany

2018/05/21 The effect of disruptive technologies on the European academic education system, especially in engineering Prof. Dr.-Ing. H.-J. Bargstädt 21/05/2018 InstituteProf. for Construction Dr.-Ing. Engineering Hans-Joachim and Management Bargstädt1 Bauhaus-Universität Weimar The effect of disruptive technologies on the European academic education system, especially in engineering • Bauhaus 1919 • Designing study programs • How to facilitate disruptions Prof. Dr.-Ing. H.-J. Bargstädt 21/05/2018 InstituteProf. for Construction Dr.-Ing. Engineering Hans-Joachim and Management Bargstädt2 Bauhaus-Universität Weimar 1 2018/05/21 Berlin Berlin Dessau Frankfurt Weimar München Prof. Dr.-Ing. H.-J. Bargstädt 21/05/2018 Institute for Construction Engineering and Management 3 History of the University, I 1860 The Grand Duke Carl Alexander founded the School of Fine Arts in Weimar. Its most prominent students were Max Liebermann and Max Beckmann. 1907 The Belgian architect Henry van de Velde founded the School of Arts and Crafts. Shortly thereafter, he designed two new buildings, known as the Van-de-Velde ensemble, which are now registered as World Heritage Sites by the UNESCO. 1919 Walter Gropius founded the State Bauhaus in Weimar. The courses in the avant-garde were significantly influenced by Johannes Itten, Lyonel Feininger, Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky. Bauhaus-Universität Weimar, 21 May 2018 www.uni-weimar.de Staircase in the Main Building 2 2018/05/21 Disruptive Technology, 1919 Gründer des Bauhauses 1919: Walter Gropius Architekt Walter Gropius Manifest 1919: Das Endziel aller bildnerischen Tätigkeit ist der Bau! Ihn zu schmücken war einst die vornehmste Aufgabe der bildenden Künste, sie waren unablösliche Bestandteile der großen Baukunst. -

MIES NO WEISSENHOF MIES at WEISSENHOF Humberto Mezzadri Tradução Português-Inglês: Carlos Eduardo Comas ARQ TEXTO 13 ARQ TEXTO 13

MIES NO WEISSENHOF MIES AT WEISSENHOF Humberto Mezzadri Tradução português-inglês: Carlos Eduardo Comas TEXTO 13 TEXTO 13 ARQ ARQ Edifício de apartamentos de Mies van der Rohe, apartamento 10. Mies van der Rohe’s apartment building, apartment 10. 26 27 Em 1927 Mies van der Rohe estabelece definitivamen- Mies van der Rohe establishes definitely in 1977 the formal te o vocabulário formal que o consagra como um dos vocabulary that turns him into one of the true masters of Modern luminares da arquitetura moderna. Sendo o Pavilhão de architecture. The Barcelona Pavilion and the Tugendhat Houde TEXTO 13 TEXTO 13 Barcelona e a casa Tugendhat as obras mais conspícuas are the most conspicuous works of this vocabulary. The apart- ARQ desse vocabulário, o edifício de apartamentos que constrói ment building that he puts up at Weissenhof gets lost amidst ARQ em Weissenhof perde-se no conjunto da mostra Die Woh- the whole of the Die Wohnung eexhibition and has not been nung e não tem sido compreendido e interpretado como understood and interpreted as a capital work. obra capital. The reasons for such cloudiness are several and they are As razões para este enevoamento são variadas e rooted in the Miesian historio graphy itself. It is Philip Johnson enraizam-se na própria historiografia miesiana. É Philip who will give first rank to the pair Barcelona-Tugendhat in the Johnson quem vai dar o primeiro lugar ao conjunto Barce- affirmation of a definitive and absolute image of modern space. lona-Tugendhat na afirmação de uma imagem de espaço That happened already in his writings of the 1930s and, in a moderno; definitiva e absoluta. -

S 33 S 34 1926 1929

1926 1929 S33 S34 Design Mart Stam Mart Stam, born 1899 in Purmerend in the Nether- lands, was among the leaders of Modern Architecture and apioneer in contemporary furniture design. He attracted much attention in 1927 with his archi- tectural contribution to the Weißenhof project in Stuttgart both as an architect and as adesigner experimenting with tubular steel. In 1928 and 1929 he worked as an architect in Frankfurt, where he helped build the Hellerhof housing estate, among other projects. At the same time he served as aguest lecturer at the Bauhaus, teaching elementary construction theory and urban planning. From 1930 to 1934, Mart Stam was active in Russia and other countries; he subsequently worked as an architect in Amsterdam until 1948. In 1939 he assumed the top position at the Academy of Arts and Crafts in Amsterdam, and in 1950 he was named director of the Conservatory for Applied Art in Berlin-Weißensee. He returned to Amsterdam in 1953 but emigrated to Switzerland in 1977, where he died on February 23, 1986, in Goldach. Free-swinging instead of anchored on four legs: a new type of chair makes history.In1926, Mart Stam began experimenting with gas pipes and bent metal, and used them to develop the principle of acanti- levered chair that no longer needed four legs for stability –afirst in the history of furniture. When he presented his groundbreaking chair without back legs to the public in 1927, at the opening of the Weissenhof development in Stuttgart, he launched a construction principle that –against the background of the formal restraint called for by the Bauhaus and modern architectural theory –would play an impor- tant role in the history of modern furniture design. -

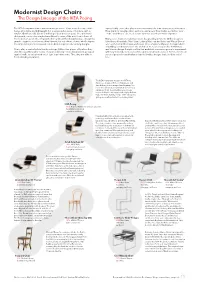

Modernist Design Chairs the Design Lineage of the IKEA Poäng

Modernist Design Chairs The Design Lineage of the IKEA Poäng The IKEA Poäng armchair is a modern design classic. It has a timeless style, while Symbolically, chairs also play a more important role than other pieces of furniture. being affordable and lightweight. It is a very popular piece of furniture, with a They stand for social position, authority, and power. Even today, words like “seat”, total of 30 million sold, about 1.5 million per year in recent years. The armchair’s “chair”, and “throne” are used as synonyms for specific positions of power. design and construction can be traced back to some of the most iconic chairs of the modernist epoch. The infographic below shows this design lineage. Though this Many iconic chairs of modernism were designed by architects. Of the designers graphic suggests a continuous development, it is not always clear to which degree listed here, Alvar Aalto, Mart Stam, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Marcel Breuer the named designers consciously referred back to previously existing designs. were architects in their main profession. These chairs mostly were the byproducts of building constructions were the architects were also responsible for furniture Chairs play a central role in furniture design. Unlike other pieces of furniture they and interior design. It might well be that architects were more prone to experiment stand freely within public rooms. They are seldomly covered by blankets, propped with new materials such as steel tube and bent laminated wood. Architect’s refined against walls, or only placed out of sight in private rooms. Thus, they are alike to sense of proportion and balance lead to timeless designs that stood the test of freely standing sculptures.