Private Investment in Urban Regeneration Process: the Case of Golden Horn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GAZİANTEP ZEUGMA MOZAİK MÜZESİ We Have a New Museum: Gaziantep Zeugma Mozaic Museum

EKİM-KASIM-ARALIK 2011 OCTOBER-NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 2011 SAYI 3 ISSUE 3 Yeni bir müzemiz oldu: GAZİANTEP ZEUGMA MOZAİK MÜZESİ We have a new museum: Gaziantep Zeugma Mozaic Museum KÜLTÜRE ve SANATA CAN SUYU: DÖSİMM Life line support for history, culture and art: DÖSİMM TOKAT ATATÜRK EVİ ve Etnografya Müzesi The Atatürk House and Etnographic Museum in Tokat Başarısını talanıyla gölgeleyen SCHLIEMANN Schliemann who overshadowed his success with his pillage MEDUSA: Mitolojinin yılan saçlı kahramanı Medusa: Mythological heroine with snakes for hair İSTANBUL ARKEOLOJİ MÜZELERİ KOLEKSİYONUNDAN IYI ÇOBAN ISA İyi Çoban İsa ensesine oturttuğu koçun ayaklarını sağ eli ile tutmuştur. Kısa bir tunik giymiş olup giysisini belinden bir kuşakla bağlamıştır. Başını yukarı doğru kaldırmıştır. Kısa dalgalı saçları yüzünü çevirmektedir. Sırtındaki koçun anatomik yapısı çok iyi işlenmiştir. Ana Sponsor İstanbul Arkeoloji Müzeleri TÜRSAB’ın desteğiyle yenileniyor İstanbul Arkeoloji Müzeleri Osman Hamdi Bey Yokuşu Sultanahmet İstanbul • Tel: 212 527 27 00 - 520 77 40 • www.istanbularkeoloji.gov.tr EKİM-KASIM-ARALIK 2011 OCTOBER-NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 2011 SAYI 3 ISSUE 3 Yeni bir müzemiz oldu: GAZİANTEP ZEUGMA içindekiler MOZAİK MÜZESİ We have a new museum: Gaziantep Zeugma Mozaic Museum KÜLTÜRE ve SANATA CAN SUYU: DÖSİMM Life line support for history, culture and art: DÖSİMM TOKAT ATATÜRK EVİ ve Etnografya Müzesi The Atatürk House and Etnographic Museum in Tokat Başarısını talanıyla gölgeleyen SCHLIEMANN Schliemann who overshadowed his success with his pillage MEDUSA: Mitolojinin yılan saçlı kahramanı Medusa: Mythological heroine with snakes for hair 5 Başyazı Her taşı bir tarih sahnesi 22 Dünya tarihinin ev sahibi BRITISH MUSEUM 8 36 KÜLTÜRE ve SANATA can suyu 46 Taşa çeviren bakışlar Tarihin AYAK İZLERİ.. -

CONSTANTINOPLE COMPOSITE the PLEIADES PATTERN the 7 Hills of the Golden Horn by Luis B

CONSTANTINOPLE COMPOSITE THE PLEIADES PATTERN The 7 Hills of the Golden Horn by Luis B. Vega [email protected] www.PostScripts.org The purpose of this illustration is to suggest that the Golden Horn of the ancient city of Constantinople is configured to the Cydonia, Mars pyramid complex. The Martian motif consists of a 7 pyramid Pleiadian City, the giant Pentagon Pyramid and the Face of Mars or that of a supposed mausoleum to the demigod, Ala-lu. What is unique about this 2nd Roman Capital founded by the Emperor Constantine in 330 AD is that the breath of the Horn or peninsula is laid out in the approximate depiction of the Pleiades star cluster corresponding to the 7 hills of the Golden Horn. During the Roman and Byzantium periods, the 7 hills corresponded to various religious monasteries or churches as were with its twin capital of Rome with its 7 hills. The most prominent being the Hagia Sophia basilica or Holy Wisdom from the Greek. One of the main reasons the move of imperial capitals was made from Rome to Constantinople was because Rome was being sacked so many times by the northern Germanic tribes. Since the fall of Constantinople to the Muslims in 1453 the various churches have been converted into mosques. The name of Constantinople was changed to Istanbul by the Ottoman Turks who are Asiatic and used the Greek word for ‘The City’. The Golden Horn is in the European site of the Straits of the Bosphorus. The other celestial association with this Golden Horn is that it is referencing to the constellation of Taurus in which the Pleaides are situated. -

Cagaloglu Hamam 46 Ecumenical Patriarchate

THIS SIDE OF THES GOLDEN Yerebatan Cistern 44 Spiritual brothers: The HORN: THE OLD TOWN AND Cagaloglu Hamam 46 Ecumenical Patriarchate EYUP 8 Nuruosmaniye Mosque 48 of Constantinople 84 Topkapi Palace 10 Grand Bazaar 50 Fethiye Mosque (Pamma- The Power and the Glory Knotted or woven: The Turkish karistos Church) 86 of the Ottoman Rulers: art of rug-making 52 Chora Church 88 Inside the Treasury 12 Book Bazaar 54 Theodosian City Wall 90 The World behind the Veil: Traditional handicrafts: Eyiip Sultan Mosque 92 Life in the Harem 14 Gold and silver jewelry 56 Santralistanbul Center of Hagia Eirene 16 Beyazit Mosque 58 Art and Culture 94 Archaeological Museum 18 Siileymaniye Mosque 60 Fountain of Sultan Ahmed 20 Rustem Pa§a Mosque 64 BEYOND THE GOLDEN Hagia Sophia 22 Egyptian Bazaar HORN:THE NEWTOWN Constantine the Great 26 (Spice Bazaar) 66 AND THE EUROPEAN SIDE Sultan Ahmed Mosque Yeni Mosque, OF THE BOSPHORUS 96 (Blue Mosque) 28 Hiinkar Kasri 68 Karakoy (Galata), Tophane 98 Arasta Bazaar 32 Port of Eminonii 70 Jewish life under the The Great Palace of the Galata Bridge 72 Crescent Moon 100 Byzantine Emperors, Myths and legends: The Istanbul Modern Museum 102 Mosaic Museum 34 story(ies) surrounding Shooting stars above the Istanbul's Traditional the Golden Horn 74 gilded cage of art: Wooden Houses and Sirkeci train station 76 Istanbul Biennal 104 the Ravages of Time 36 $ehzade Mosque Kilig Ali Pa§a Mosque, The Hippodrome 38 (Prince's Mosque) 78 Nusretiye Mosque 106 Sokollu Mehmet Pa§a Valens Aqueduct 80 Galata Tower 108 Mosque 40 Fatih -

Refik Anadol CV Eng

REFİK ANADOL 1985 Istanbul, Turkey Lives and works in Los Angeles, CA, USA SELECTED EXHIBITIONS 2021 Machine Memoirs: Space, Pilevneli Gallery, Istanbul, Turkey 2019 Machine Hallucination, Artechouse, New York City, USA Latent History, Fotografiska, Stockholm, Sweden Infinite Space, Artechouse, Washington, DC, USA Macau Currents: Data Paintings, Art Macao: International Art Exhibition, Macao, China Archive Dreaming, Symbiosis – Asia Digital Art Exhibition, Beijing, China Machine Hallucination – Study II, Hermitage Museum, Moscow, Russia Memoirs from Latent Space, New Human Agenda, Akbank Sanat, Istanbul, Turkey Melting Memories – Engram – LEV Festival, Gijón, Spain Machine Hallucination – Study I, Bitforms Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, USA Infinity Room / New Edition, ZKM, Karlsruhe, Germany Bosphorus, At The Factory: 10 Artists / 10 Individual Practices PİLEVNELİ Mecidiyeköy, Istanbul, Turkey Infinity Room / New Edition, Wood Street Gallery, Pittsburgh, PA, USA 2018 WDCH Dreams, Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles, California Melting Memories, PİLEVNELİ Dolapdere, Istanbul, Turkey Infinity Room/New Edition, New Zealand Festival, Wellington, New Zealand Virtual Archive, SALT Galata, Istanbul, Turkey Liminality V1.0, International Art Projects, Hildesheim, Germany Infinity Room / New Edition, Kaneko Museum, Omaha, Nebraska The Invisible Body : Data Paintings, Sven-Harrys Museum, Stockholm, Sweden Data Sculpture Series, Art Center Nabi, Seoul, South Korea 1-2-3 Data Exhibition, Paris, EDF, France Infinity Room, Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary -

![Fall of Constantinople] Pmunc 2018 Contents](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3444/fall-of-constantinople-pmunc-2018-contents-1093444.webp)

Fall of Constantinople] Pmunc 2018 Contents

[FALL OF CONSTANTINOPLE] PMUNC 2018 CONTENTS Letter from the Chair and CD………....…………………………………………....[3] Committee Description…………………………………………………………….[4] The Siege of Constantinople: Introduction………………………………………………………….……. [5] Sailing to Byzantium: A Brief History……...………....……………………...[6] Current Status………………………………………………………………[9] Keywords………………………………………………………………….[12] Questions for Consideration……………………………………………….[14] Character List…………………...………………………………………….[15] Citations……..…………………...………………………………………...[23] 2 [FALL OF CONSTANTINOPLE] PMUNC 2018 LETTER FROM THE CHAIR Dear delegates, Welcome to PMUNC! My name is Atakan Baltaci, and I’m super excited to conquer a city! I will be your chair for the Fall of Constantinople Committee at PMUNC 2018. We have gathered the mightiest commanders, the most cunning statesmen and the most renowned scholars the Ottoman Empire has ever seen to achieve the toughest of goals: conquering Constantinople. This Sultan is clever and more than eager, but he is also young and wants your advice. Let’s see what comes of this! Sincerely, Atakan Baltaci Dear delegates, Hello and welcome to PMUNC! I am Kris Hristov and I will be your crisis director for the siege of Constantinople. I am pleased to say this will not be your typical committee as we will focus more on enacting more small directives, building up to the siege of Constantinople, which will require military mobilization, finding the funds for an invasion and the political will on the part of all delegates.. Sincerely, Kris Hristov 3 [FALL OF CONSTANTINOPLE] PMUNC 2018 COMMITTEE DESCRIPTION The year is 1451, and a 19 year old has re-ascended to the throne of the Ottoman Empire. Mehmed II is now assembling his Imperial Court for the grandest city of all: Constantinople! The Fall of Constantinople (affectionately called the Conquest of Istanbul by the Turks) was the capture of the Byzantine Empire's capital by the Ottoman Empire. -

TURKEY Threats to the World Heritage in the Changing Metropolitan Areas of Istanbul

Turkey 175 TURKEY Threats to the World Heritage in the Changing Metropolitan Areas of Istanbul The Historic Areas of Istanbul on the Bosporus peninsula were in- scribed in 1985 in the World Heritage List, not including Galata and without a buffer zone to protect the surroundings. Risks for the historic urban topography of Istanbul, especially by a series of high- rise buildings threatening the historic urban silhouette, were already presented in Heritage at Risk 2006/2007 (see the visual impact as- sessment study by Astrid Debold-Kritter on pp. 159 –164). In the last years, dynamic development and transformation have changed the metropolitan areas with a new scale of building inter- ventions and private investments. Furthermore, the privatisation of urban areas and the development of high-rise buildings with large ground plans or in large clusters have dramatically increased. orld eritagea,,eerules and standards set upby arely knownconveyrthe ap- provedConflicts in managing the World Heritage areas of Istanbul Metropolis derive from changing the law relevant for the core area- sisthe . Conservation sites and areas of conservation were proposed in 1983. In 1985, the historic areas of Istanbul were inscribed on the basis of criteria 1 to 4. The four “core areas”, Archaeological Park, Süleymaniye conservation site, Zeyrek conservation site, and the Theodosian land walls were protected by Law 2863, which in Article I (4) gives a definition of “conservation” and of “areas of conservation”. Article II defines right and responsibility: “cultural and natural property cannot be acquired through possession”; article Fig. 1. Project for Diamond of Dubai, 2010, height 270 m, 53 floors, Hattat 17 states that “urban development plans for conservation” have to Holding Arch. -

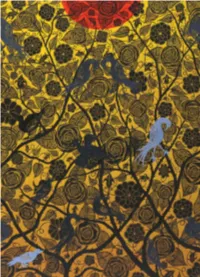

Selma-Gurbuz-Final2.Pdf

Selma Gurbuz Mind’s Eye 24October – 7 December 2011 In association with “This exhibition mostly consists of works I had made in my studio in Istanbul in 2011. I always put a full stop after each exhibition and begin with a new clean sheet. Actually, the things that should have been said were told in the first few sentences, but the real sentence is still incomplete. What brings me to the process of this second exhibition is the need to complete this sentence. Before that, I held an exhibition called Shadows of My Self at Leighton House Museum in London. Now, with this exhibition, I will continue to form the incomplete sentence. I think that the Western tradition and the tradition of the Eastern pole are actually two separate fluid materials intertwined. I try to imagine the West from the East as how the West would imagine the East. When setting up my own dream, I generate a view from East to West by knowing both the Western art and culture and using the richness of this region such as being in between East and West. When I interpret Western myths through the eyes of the Eastern, the Eastern myths that I have created show up, too.They also have a nature that occurs with these myths. There is not an indication on a definite location. Geographies are undefined in my pictures.” Selma Gürbüz. Selma Gürbüz is nothing if not eclectic. She knows her more prominent and, more recently, the details in her sources and is not afraid to mix idioms. -

REGENERATION of GOLDEN HORN AS a “CULTURAL VALLEY”

The Turkish Online Journal of Design, Art and Communication - TOJDAC ISSN: 2146-5193, October 2019 Volume 9 Issue 4, p. 491-513 FROM INDUSTRY TO CULTURE: REGENERATION of GOLDEN HORN AS A “CULTURAL VALLEY” Ceyda BAKBAŞA BOSSON École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5490-3019 Evrim TÖRE İstanbul Kültür University, Turkey [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6720-0232 ABSTRACT The image shifts from industrial identity to cultural identity since 1980s in Golden Horn, one of Istanbul’s former industrial areas, encompassed cultural policies and urban regeneration processes in the area. This study discusses the positions of public and private sector investments in the region during the process of creating "The Golden Horn Cultural Valley" and reveals the policies that managed this regeneration. The research uses a multi-dimensional method considering both qualitative and quantitative data throughout economics, politics/urban cultural policies, society, culture and space. With respect to the projects, the authors highlight three main outcomes: (1) processes vary according to the actors, (2) lack of integrated vision and (3) disconnected cultural visibility. Keywords: post-industrial space, entrepreneurialism, Golden Horn, culture-led regeneration, urban policies, arts. SANAYİDEN KÜLTÜRE: HALİÇ’İN “KÜLTÜR VADİSİ”NE DÖNÜŞÜMÜ ÖZ 1980'lerden bu yana sanayi kimliğinden kültürel kimliğe geçiş, İstanbul'un eski sanayi bölgelerinden biri olan Haliç'te, bölgedeki kültürel politikaları ve kentsel dönüşüm süreçlerini kapsamıştır. Bu çalışma “Haliç Kültürü Vadisi” oluşturma sürecinde bölgedeki kamu ve özel sektör yatırımlarının konumlarını tartışmakta ve bu yenilenmeyi yöneten politikaları ortaya koymaktadır. Araştırmada, ekonomi, siyaset/kentsel kültür politikaları, toplum, kültür ve mekan üzerine hem nitel hem de nicel verileri dikkate alan çok boyutlu bir metodoloji kullanılmaktadır. -

The Golden Horn: Heritage Industry Vs

Uludağ Üniversitesi Mühendislik Fakültesi Dergisi, Cilt 19, Sayı 2, 2014 ARAŞTIRMA THE GOLDEN HORN: HERITAGE INDUSTRY VS. INDUSTRIAL HERITAGE Zeynep GÜNAY * Abstract: The revitalization of former industrial areas has been one of the crucial tasks of urban policy agenda throughout the world since the mid 1970s; whereas heritage industry has become the new orthodoxy in the shift from production to consumption as means for the restructuring and reimaging of post-industrial economies in the global order. The increasing tendency to link heritage and conservation with economic development has brought new meanings to cultural assets, the value of which has started to be related solely to the economic value it sustains or generates. The commodification and instrumentalization of industrial heritage by the heritage industry, in particular, has turned out to be the determining factor for creating opportunity spaces in the post-industrial areas. At the same time, many academics are critical on the attempts to reform post-industrial spaces of consumption with privatized spaces and commodified cultures. Within this context, the paper attempts to evaluate the role and the impact of heritage industry in the revitalisation of the post-industrial spaces of Istanbul, with a case study on the Golden Horn. The results of the paper are related to the following questions: What role the industrial heritage play in the revitalisation of historic environments? What are the ways to turn such industrial heritage into sources of social and economic development? What are the likely impacts on the local economy and local community? The conclusion gives an overview of the extent of the impacts that industrial heritage has on the Golden Horn, and in turn relates this back to the wider idea of heritage industry being promoted for the urban policy- making in Istanbul. -

A Case of Energy Museum in Sanatistanbul, Turkey MA

Journal of Contemporary Urban Affairs 2017, Volume 1, Number 1, pages 24– 34 Adaptive Reuse of the Industrial Building: A case of Energy Museum in Sanatistanbul, Turkey MA. Najmaldin Hussein Department of Architecture, Faculty of Architecture, Eastern Mediterranean University, Turkey A R T I C L E I N F O: A B S T R A C T Article history: Industrial buildings as an example of cultural heritage transforms our cultural identity Received 20 September 2016 from past to the present and even for the future. Unfortunately, there are lots of Received in revised form 5 industrial building which lost its function by converting the place to live and December 2016 identifiable place. This research will clarify the reasons of conserving of the industrial Accepted 20 January 2017 heritage and by classification of international charters which are dealing with Available online 2 January industrial heritage will introduce conservation methods for adaptive reuse of industrial 2017 buildings. As a case study, the research will focus on Energy Museum in Istanbul. To Keywords: assess the building based on reusing principals. The study concludes that Energy Industrial Building; Museum is one of the successful examples of reuse of the building. It also concludes Adaptive Reuse; that less intervention in reusing a building can save the identity of the building. Conservation methods; Energy Museum; JOURNAL OF CONTEMPORARY URBAN AFFAIRS (2017) 1(1), 24-34. Gentrification; https://doi.org/10.25034/1761.1(1)24-34 Sanatistanbul. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivs 4.0. "CC-BY-NC-ND" www.ijcua.com Copyright © 2017 Journal Of Contemporary Urban Affairs. -

Public Istanbul

Frank Eckardt, Kathrin Wildner (eds.) Public Istanbul Frank Eckardt, Kathrin Wildner (eds.) Public Istanbul Spaces and Spheres of the Urban Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbib- liothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deut- sche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de © 2008 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Cover layout: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Cover illustration: Kathrin Wildner, Istanbul, 2005 Proofred by: Esther Blodau-Konick, Kathryn Davis, Kerstin Kempf Typeset by: Gonzalo Oroz Printed by: Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar ISBN 978-3-89942-865-0 CONTENT Preface 7 PART 1 CONTESTED SPACES Introduction: Public Space as a Critical Concept. Adequate for Understanding Istanbul Today? 13 FRANK ECKARDT Mapping Social Istanbul. Extracts of the Istanbul Metropolitan Area Atlas 21 MURAT GÜVENÇ Contested Public Spaces vs. Conquered Public Spaces. Gentrification and its Reflections on Urban Public Space in Istanbul 29 EDA ÜNLÜ YÜCESOY Globalization, Locality and the Struggle over a Living Space. The Case of Karanfilköy 49 SEVIL ALKAN Fortress Istanbul. Gated Communities and the Socio-Urban Transformation 83 ORHAN ESEN/TIM RIENIETS Peripheral Public Space. Types in Progress 113 ELA ALANYALI ARAL Old City Walls as Public Spaces in Istanbul 141 FUNDA BA BÜTÜNER Regenerating »Public Istanbul«. Two Projects on the Golden Horn 163 SENEM ZEYBEKOLU Public Transformation of the Bosporus. Facts and Opportunities 187 EBRU ERDÖNMEZ/SELIM ÖKEM PART 2 EXPERIENCING ISTANBUL Introduction: Spaces of Everyday Life 209 KATHRIN WILDNER Istanbul's Worldliness 215 ASU AKSOY Public People. -

20Th Annual Meetıng of the European Assocıatıon Of

20th Annual Meetıng 20thof the Annual European Meetıng ofAssocıatıon the European Assocıatıonof Archaeologısts of Archaeologısts In Memoriam Sevgi Gönül In Memoriam Sevgi Gönül Programme Programme 10-14 September 2014 Istanbul | Turkey 10-14 September 2014 Istanbul | Turkey CONTENTS General Programme of the EAA 2014 Istanbul Meeting .....................................V Programme of the Opening Ceremony .............................................................VII EAA Secretariat – Annual Business Meeting .....................................................VIII The Venues and Taksim District .......................................................................... IX Special Exhibits and Events............................................................................... XIII Social Programme.............................................................................................XIV Exhibition........................................................................................................XVIII Sponsors ......................................................................................................... XXIX General Poster Session .................................................................................. XXXII Book of Abstracts .......................................................................................... XXXII Oral Presentations and Handing in Power Point ...........................................XXXII Scientific Programme ...................................................................................