View Steve Jansen Catalogue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Live Among the White Trash: a History of Nono----Manman on Stage

Live Among the White Trash: A history of nono----manman on stage “There are no No-Man concerts scheduled for the foreseeable future.” (from the official no-man website) Anyone who has followed no-man’s career over the previous ten years or so will be acutely aware that the band does not play live. If no-man “exist” as a band at all – and their infrequent releases mean they are more an ongoing understanding between two men rather than an active unit – it is only in the studio. Over a series of uncompromising albums no-man’s music has become ever more complex, yet ironically, “live sounding” than the release which proceeded it. But this organic “liveness” is mainly an illusion; the feeling of spontaneity often the result of numerous edits and takes which only the precision of studio work can produce. Others have tried to perform equally difficult music live: Radiohead ambitiously thrusting their clicks-and- cuts post-rock upon the world’s stadiums, for example. But for a variety of reasons, no-man simply haven’t tried – at least, not since 1994 and not until a one-off performance in 2006. The only comparable case is Talk Talk’s retreat into the studio in the late 1980s. Both bands have undoubtedly crafted their best work without going near an audience. 1 But it wasn’t always so. no-man were once very much a live act, promoting singles and albums with dates and undertaking two full-blown tours – though they rarely played outside London, never went further north than Newcastle, and never played outside Great Britain. -

Japan Tin Drum Japan Edition 19812008 FLAC EMI Mus

Japan - Tin Drum (Japan Edition) (1981,2008) [FLAC] {EMI Mus Japan - Tin Drum (Japan Edition) (1981,2008) [FLAC] {EMI Mus 1 / 2 Japan - Tin Drum (Japan edition) (1981,2008) [FLAC] {EMI Mus. Join the campaign and make a difference.. Title: Japan - Tin Drum (Japan Edition) (1981,2008) [FLAC] {EMI Mus, Author: molamere, Name: Japan - Tin Drum (Japan Edition) (1981,2008) .... ... gestionnaire de menu" mais j'ai vu dans un post que la nouvelle version de prestashop 1 . ... Japan - Tin Drum (Japan edition) (1981,2008) [FLAC] {EMI Mus. Mp3 is a compressed version of the original recorded CD. ... registration key Japan - Tin Drum (Japan edition) (1981,2008) [FLAC] {EMI Mus Fifa15 Data1 Bin.. The Art Of Parties (re-recorded version); Talking Drum; Ghosts; Canton; Still Life In ... Japanese 1987 re-issue LP Virgin/Toshiba-EMI 25VB-1014; Japanese 1987 ... The same obi design is used for the 2008 Japanese mini LP CD remaster. Tin .... JAPAN - Tin Drum - Amazon.com Music. ... Amazon's Choice for "japan tin drum" ... Complete your purchase to save the MP3 version to your music library. ... Digitally remastered reissue, in standard jewel case, of their ground breaking 1981 .... ... Previous Message ] Date Posted: 21:01:59 02/25/14 Tue Author: folkmamb. Subject: Japan - Tin Drum (Japan Edition) (1981,2008) [FLAC] {EMI Mus. > .... Genre: Electronic, Pop. Style: New Wave, Synth-pop. Year: 1981 .... Japan tin drum japan edition 1981 2008 flac emi mus zip. Thus with the literary references for singer, David Sylvian), Tin Drum remains Japan' s most Eastern- .... Released 1981. ... Tin Drum has no flashy waste or needless bombast, just evocative skill that remains.. -

FPL Snag Leads to Blackouts by WILLIAM WACHSBERGER Blew," White Explained

RUSSIAN PORCELAIN BULLS NEXT FOR UM Lowe exhibit features Russia's rich, Two-game series at University of South artistic past. Florida next for surging Hurricanes after FRIDAY 7-4 victory over FIU. ACCENT, page 6 SPORTS, page 8 FEBRUARY 24, 1995 VOLUME 72, NUMBER 36 ****** RESERVE AN ASSOCIATED COLLEGIATE PRESS HALL OF FAME NEWSPAPER FPL snag leads to blackouts By WILLIAM WACHSBERGER blew," White explained. "They had to go to an auxil "I was on my computer working on a project when • FP&L Managing Editor iary feed to restore power the lights went out. Fortunately, I have an auto andUM The wind was calm. The skies were clear. The air "What was supposed to be a five-minute shutdown saver," he said. "I immediately went out to talk to was a cool 55 degrees. Then, the lights went out. became a 30-minute power outage," said White. some of the residents to see what was going on." officials The University suffered a partial blackout twice in Then, at approximately 2 a.m., FP&L and Physical Across the street at Eaton Residential College, AIDS WALK TO RAISE the early morning hours Wednesday, thus causing Plant personnel attempted to switch feeds again. sophomore A.J. Dickerson was visiting a friend dur say power confusion and a bit of pandemonium amongst resi However, they hit another snag, causing another out ing the first power failure. FUNDS, AWARENESS dential students. age. "As the lights went off, I went out in the hall where he annual AIDS Walk Miami is will be "No one knew what was going on when the emer White said that "a significant part of the campus this guy came out of his dorm screaming 'No! No!' from 9:30 a.m. -

Steve Jansen – Tender Extinction

Steve Jansen – Tender Extinction (48:20, CD, A Steve Jansen Production, 2016) Bereits im April dieses Jahres erschien das aktuelle Soloalbum des Ex-Japaners Steve Jansen. War der Vorgänger „Slope“ noch auf Samadhi Sound, dem Label seines Bruders David Sylvian herausgekommen, ist „Tender Extinction“ im Eigenverlag über Bandcamp veröffentlicht worden. Erneut versammelte Jansen eine ganze Reihe hochkarätiger Gäste für sein Album. Es sind dieses Mal hauptsächlich Gast- Vokalisten und -Vokalistinnen. Sein BruderDavid gibt allerdings weiterhin den Waldschrat und war dieses Mal nicht dabei. Zum Einstieg gibt sich der Schwede Thomas Feiner die Ehre und liefert Gesang und Text zu ‚Captured‘. Das dunkel- symphonische Stück gibt die Marschrichtung des Albums vor und wirkt geradezu beschwörend bedrohlich – „Something left, and died out there“. Auch das von Perkussion dominierte ‚Her Distance‘ mit Gastsänger und Texter Perry Blake setzt auf beschwörende Gesangslinien und dunkle Atmosphäre. Insbesondere dieses Stück lässt Erinnerungen an das Cameo-Japan-Album „Rain Tree Crow“ aufkommen. Zwischen den gewichtigen Vokalstücken platzierteJansen Ambient-artige Instrumentals und Miniaturen, die dem Werk einen sanften Fluss geben. Tim Elsenburg (‚Give Yourself A Name‘) und Nicola Hitchcock (‚Faced With Nothing‘) verleihen den von ihnen gesungenen Stücken mit ihrehn markanten Stimmen einen sehr eindringlichen Charakter.Jansen selbst am Mikrophon beendet das Album mit dem sanften ‚And Bird Sing All Night‘, wobei er wiederum seinem berühmten Bruder zum Verwechseln ähnlich klingt. Tja, die Gene. Dass „Tender Extinction“ nicht als Stimmungsaufheller taugt, versteht sich somit von selbst. Herbstlicher Schwermut durchzieht dieses Werk. Das quirlig-elektronische Element, das Steve Jansens Album „Slope“ auszeichnete, wurde für „Tender Extinction“ ersatzlos gestrichen. Die Zusammenarbeit mit den genannten Sängern und Sängerinnen und eine eher sparsam symphonische Ausrichtung bringt hier Spannung auf einem anderen Terrain hervor. -

Music & Entertainment

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Forrester Director Shuttleworth Director Director Music & Entertainment Tuesday 18th & Wednesday 19th May 2021 at 10:00 Viewing by strict appointment from 6th May For enquires relating to the Special Auction Services auction, please contact: Plenty Close Off Hambridge Road NEWBURY RG14 5RL Telephone: 01635 580595 Email: [email protected] www.specialauctionservices.com David Martin Dave Howe Music & Music & Entertainment Entertainment Due to the nature of the items in this auction, buyers must satisfy themselves concerning their authenticity prior to bidding and returns will not be accepted, subject to our Terms and Conditions. Additional images are available on request. Buyers Premium with SAS & SAS LIVE: 20% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24% of the Hammer Price the-saleroom.com Premium: 25% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 30% of the Hammer Price 10. Iron Maiden Box Set, The First Start of Day One Ten Years Box Set - twenty 12” singles in ten Double Packs released 1990 on EMI (no cat number) - Box was only available The Iron Maiden sections in this auction by mail order with tokens collected from comprise the first part of Peter Boden’s buying the records - some wear to edges Iron Maiden collection (the second part and corners of the Box, Sleeves and vinyl will be auctioned in July) mainly Excellent to EX+ Peter was an Iron Maiden Superfan and £100-150 avid memorabilia collector and the items 4. Iron Maiden LP, The X Factor coming up in this and the July auction 11. Iron Maiden Picture Disc, were his pride and joy, carefully collected Double Album - UK Clear Vinyl release 1995 on EMI (EMD 1087) - Gatefold Sleeve Seventh Son of a Seventh Son - UK Picture over 30 years. -

Leksykon Polskiej I Światowej Muzyki Elektronicznej

Piotr Mulawka Leksykon polskiej i światowej muzyki elektronicznej „Zrealizowano w ramach programu stypendialnego Ministra Kultury i Dziedzictwa Narodowego-Kultura w sieci” Wydawca: Piotr Mulawka [email protected] © 2020 Wszelkie prawa zastrzeżone ISBN 978-83-943331-4-0 2 Przedmowa Muzyka elektroniczna narodziła się w latach 50-tych XX wieku, a do jej powstania przyczyniły się zdobycze techniki z końca XIX wieku m.in. telefon- pierwsze urządzenie służące do przesyłania dźwięków na odległość (Aleksander Graham Bell), fonograf- pierwsze urządzenie zapisujące dźwięk (Thomas Alv Edison 1877), gramofon (Emile Berliner 1887). Jak podają źródła, w 1948 roku francuski badacz, kompozytor, akustyk Pierre Schaeffer (1910-1995) nagrał za pomocą mikrofonu dźwięki naturalne m.in. (śpiew ptaków, hałas uliczny, rozmowy) i próbował je przekształcać. Tak powstała muzyka nazwana konkretną (fr. musigue concrete). W tym samym roku wyemitował w radiu „Koncert szumów”. Jego najważniejszą kompozycją okazał się utwór pt. „Symphonie pour un homme seul” z 1950 roku. W kolejnych latach muzykę konkretną łączono z muzyką tradycyjną. Oto pionierzy tego eksperymentu: John Cage i Yannis Xenakis. Muzyka konkretna pojawiła się w kompozycji Rogera Watersa. Utwór ten trafił na ścieżkę dźwiękową do filmu „The Body” (1970). Grupa Beaver and Krause wprowadziła muzykę konkretną do utworu „Walking Green Algae Blues” z albumu „In A Wild Sanctuary” (1970), a zespół Pink Floyd w „Animals” (1977). Pierwsze próby tworzenia muzyki elektronicznej miały miejsce w Darmstadt (w Niemczech) na Międzynarodowych Kursach Nowej Muzyki w 1950 roku. W 1951 roku powstało pierwsze studio muzyki elektronicznej przy Rozgłośni Radia Zachodnioniemieckiego w Kolonii (NWDR- Nordwestdeutscher Rundfunk). Tu tworzyli: H. Eimert (Glockenspiel 1953), K. Stockhausen (Elektronische Studie I, II-1951-1954), H. -

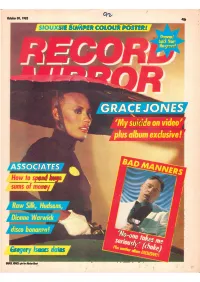

Record-Mirror-1982-1

2 October 30, 1982 TEST OUR PRICE RECORDS LATEST OUR PRICE RECORDS LATEST OUP PRICE RECORDS LATEST OUR PRICE RECOR o E BLUE HON AE RED HOT FAVOURITES THIS LAST OUR WEEK WEEK PRICE -,- 1 I 1I tD_ oi AvEEsO rvilEAnal HI 4.49 2 3 CURKIUSLSTIN ETtg l-131EIBCLEVER _4.29 3 5 sFRHIAELNADFASAn _4.29 _ AT BUB PRIC-1 4 26 VT.A rKOInFROM FAME II 4.49 5 9 outrARATvEr 4.49 6 7 TV HA E KIDS FROM FAME 4.49 7 ii TKRIDCROLe OPICAL NTGHSETCE OR CS °NUTS 4 29 833 HHAoLL & OATES 4.29 92 un 3.99 EVELYN KING 10 12 G ET LOOSE ,3' 99 11 10 DIANA ROSS SILK ELECTRIC 4.49 12 16 zureteeHrs - ..rgAupriGsTEEN 1 . 13 4 i 4.29 ADAM ANT 1 14 19 FRIEND OR FOE 4.29 IMAGINATION 15 6 IN THE HEAT OF THE NIGHT 4.49 16 15 CVSTAIRSz" AT ERIC S 3.99 DEPECHE MODE 17 13 BROKEN FRAME 3.99 FAT LARRY'S BAND 18 R- BREAKIN OUT 4.29 ASSAUEMICHA LL As fe cNKKER 19 24 3.99 20 17 NSIEmwPCLDE0PAINDDRSEAm 4.49 BAUHAUS 21 e THE SKY S GONE OUT 4.49 ABC 22 14 EXICON OF LOVE 4.49 7 23 42 eNr NAit-gr= 4.29 gi9_=siiimETAOTNE-JsoTHHNiTs 24 38 4.99 DIONNE WARWICK 25 fa HEARTBREAKER 13.99 JOEL 26 30 NEDYLLLOYNUg PI TAINS 4.49 r YeADyNEIGHT RUNNERS 27 22 4.29 28 31 TV HA ETICORY KINDA LINGERS 5.99 TOYAH 29 0 WARRIOR ROCK 5.49 raDEHDEimE 30 41 C 4.29 31 21 r oRAN DURAN 4.49 32 18 :ETEFI GABRIEL 4.49 33 25 Alt= THE GANG 4.29 34 34 CVDE1151IZAUDKNEOISE 4.49 35 27 ceeenerCersil 4.29 CHICAGO 36 40 16 4.49 37 53 CTHE HRIS IDTEA BW UARYGH 4.29 LITTLE STEVE & DISCIPLES or SOUL 38 el MEN WITHOUT WOMEN 4.29 39 44 STRAWBERRIES 3.99 40 50 CHOOSE YOUR MASQUES 4.29 OUR PRICE RECORD SHOPS OUTER LONDON CENTRAL LONDON AYLESBURY BARNET R 4.49 BISHOPSGATE 1(2 GSTOKF BPENT CROSS 41 52 Aeior CANNON STREET f .GSHOPPlTTG CENTRE BROMLEY CHA ,, NO CROSS ROAD WC 2 AMBEKEY CAMBRIDGI umNA-rniL& ETD FIE MAMBAS 42 20 3.99 CHEAPSIDE EC CANTERBURY CHATHAM COVENTRY ST*ET •.•,• CHELMSFORD (RAwuy BLANCMANGE THINK ALBUM EDGWARE ROAD CROYDON HARLOW HAPPY FAMILIES 43 28 3.99 fINCHLEY ROAD ITW) HARROW HEMEL HFMRSTEAD FLEET STREET Er 4 KATE BUSH H"CH WYCOMBE -HOUNSLOW . -

Tom Burr Body/Building

TOM BURR BODY/BUILDING BODY/BUILDING A selection of material to accompany the exhibition Tom Burr / New Haven, an Artist / City project BY ADRIAN GAUT TEXT BY MARK OWENS PHOTOGRAPHY BY ADRIAN GAUT TEXT BY MARK OWENS PHOTOGRAPH YALE ART AND ARCHITECTURE BUILDING, PAUL RUDOLPH (1963). 180 YORK STREET, BRUTAL RECALL NEW HAVEN. A SELECTIVE ROADMAP OF SOME OF NEW HAVEN’S MOST ICONIC CONCRETE LANDMARKS Entering New Haven by car along Interstate 95 offers a tour through one of America’s last remaining Brutalist corridors. Approaching the Oak Street Connector, you can still catch a glimpse of the briskly fenestrated raw-concrete façade of Marcel Breuer’s striking Armstrong Rubber Company Building (1968), which now sits vacant in a vast IKEA parking lot. Heading towards George Street along Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard, a stoplight just outside the town’s commercial center brings you momen- tarily to rest at the foot of Roche-Dinkeloo’s enigmatic Knights of Columbus Building (1969), whose 23 raw-steel stories are slung between four colossal brick-clad concrete columns. Further along the boulevard on the right rises the distinctive silhouette of Paul Rudolph’s Crawford Manor housing block (1966), whose “heroic and origi- automobile. It’s perhaps ironically fitting, then, that in order to complete this Brutalist nal” striated-cement cladding promenade you’re best off proceeding on foot. Continuing down Temple Street and was famously contrasted with making a left turn onto Chapel Street, you eventually come to the entrance of Louis the “ugly and ordinary” visage Kahn’s Yale University Art Gallery (1951–53), an expressive use of brick, concrete, and of Venturi and Rauch’s Guild curtain wall that was completed a year before the Alison and Peter Smithson’s Hun- House in the pages of Learning stanton School (Norfolk, England, 1949–54), generally considered the opening salvo from Las Vegas. -

Smash Hits Volume 63

35pUSA$l75 April 30 -May 13 1981 GIRLSCHOOL PAULWEILER THE FALL GET ENOUGH THE BANDS PlAY pRYNUMAN^ ADAM ECHO & THE B TEARDROP EX gjGS^ Vol. 3 No. 9 GREY DAY ON STIFF RECORDS THE LARCHES" lay bathed in the warm afternoon sunshine. Peregrine vas on the verandah, sipping a cool drink and dangling his toes in the When I get home it's late at night yping pool. Looking up from the Adam And The Ants colour portrait he I'm black and bloody from my life vatched a butterfly flit lazily from page to page, alighting briefly on the I haven't time to clean my hands ulian Cope feature before shooting off to inspect the Gary Numan Cuts will only sting me through my dreams entrespread. Somewhere in the distance he could hear the Head jardener whistling as he ran a heavy roller over the last part of The Jam It's well past midnight as I lie eries. In a semi-conscious state The only other sound to pierce the drowsy calm came from the back I dream of people fighting me age, where Samantha and Roderick were playing tennis on the Echo And Without any reason I can see he Bunnymen pin-up. Having completed his inspection of The Fall eature. Peregrine yawned and stretched. As Victoria began to rub the Chorus lirst of the tanning lotion into his back, he licked the end of his pencil and In the morning I awake Hon. ifl My arm* my lags my body aches The sky outside is wet and gray So begins another weary day GREY DAY Ma So begins another weary day CROCODILESJflio And Thj Builnymen After eating I go out KEEP OJpfvING YOU REO Speedwagon...|kga....8 People passing by ma shout this IT'SJPNG TO HAPPEN The Undertones....^A,9 I can't stand agony Why don't they talk to ma 1AGNIFICENT FIVE Adam And The Ants 15 the park I have to rest WIUDA TRIANGLE Barry Manilow....... -

Smash Hits Volume 65

35pUSA$i75 Mayas- June 101 ^ S */A -sen ^^ 15 HIT UfRiasmolding StandAndDe^^r iMimnliMl Being Wj LANDSCAPBin colour KIM WILDE m u ) Vol. 3 No. 11 IF YOU'VE already sneaked a peek around the back of this issue you'll have twigged the fact that you're dealing with something out of the ordinary. So welcome, friends, to the first (and the only?) double sided edition of your favourite musical publication. In effect you get two magazines, each with its own cover, bumper feature, songwords, competition and Bitz section. Soon as you get fed up of poring over this half, just flip it and play the other side. Now you may well ask why we've taken the unusual step of standing the entire magazine on its head. Well, there are a number of reasons; 1 To confuse newsagents 2) We couldn't decide who to put on the cover In 3) the hope that some dummies would buy it twice 4) For laffs THIS SIDE STAND AND DELIVER Adam And The Ants 2A NORMAN BATES Landscape .8A DON'T LET IT PASS YOU BY UB40 9A ROCKABILLY GUY Polecats 9A GHOSTS OF PRINCES IN TOWERS Rich Kids 11A IS THAT LOVE Squeeze 14A BETTE DAVIS EYES Kim Games 14A BEING Vi/ITH YOU Smokey Robinson 17A HOW 'BOUT US Champaign 19A STRAY CATS: Feature 4A/5A/6A BITZ (A) 12A/13A CARTOON 17A DISCO ISA STAR TEASER 20A THE BEAT COMPETITION 21A SINGLES REVIEWS 23A LANDSCAPE: Colour Poster The Middle THAT SIDE FUNERAL PYRE The Jam 2B HOUSES IN MOTION Talking Heads 8B THE ART OF PARTIES Japan SB BAD REPUTATION Thin Lizzy SB THEM BELLY FULL (BUT WE HUNGRY) Bob Marley 11B ANGEL OFTh£ MORNING Juice Newton 14B KIM WILDE: Feature 4B/5B/6B BITZ(B) 12B/13B UNDERTONES COMPETITION 15B LEHERS 16B/17B INDEPENDENT BITZ 1SB GIGZ 20B/21B ALBUM REVIEWS 23B The charts appearing in Smash Hits are compiled by Record Business Research from information supplied by panels of specialist shcps. -

Review Tear Sheet

FEBRUARY 2008 Synergy Magazine Review Tear Sheet Slope Steve Jansen Samadhi Sound Web: http://www.samadhisound.com Steve Jansen will not be a familiar name unless you have an interest in ‘80s art pop or spend time the end with subtle voices. Then we checking who plays backing in- have the sleeplike sound of Sleep- struments on experimental music yard offering the superb vocals of albums. Jansen is is David Syl- Tim Elsenburg and a range of tracks vian's brother, Sylvian being the which explore a variety of textures lead singer of Japan and, since and sounds, with the expert use of the early '80s, has developed atmospheric instrumentals creating quite a reputation as an innovative a truly luxurious listening experi- and creative solo artist. Jansen ence. Gap of Cloud is light and has played drums and percussion floats away and a A Way of Disap- on many of his brother's releases, pearing is haunting with a clarinet as well as working with other ex- which seem to resonate long after it members of Japan in a variety of has been played. guises. This, however, is a unique Solo album from Jansen in which Slope is a nicely structured album he has harnessed support from moving carefully through different many around him. textures and forms; it slowly envel- ops you in its atmosphere until you Featuring guest vocalists who in- quietly drift away with its ambiance. clude his brother and long-time This is a beautiful and innovative collaborator David Sylvian, and CD. the sublime Nina Kinert, it is a beautiful electronic album featur- © COPYRIGHT ing a range of different sounds; it February 2008 is textured, minimalist and deli- Synergy Magazine cate. -

Psaudio Copper

Issue 109 APRIL 20TH, 2020 This issue’s cover: Judy Garland (1922 – 1969). One of the most iconic actresses, recording artists and performers of all time. Though haunted by personal struggles, she attained greatness that few ever achieved. Somewhere over the rainbow, skies are blue. Like everyone else, we at Copper have been impacted by the coronavirus, whether by disruption in our work and home lives to financial impact, stress, anxiety and writer’s block. And yes, one of us contracted the virus – thankfully, he’s doing OK. So, over the next few issues you might see some changes – temporary absence of some writers, a different balance of articles and other differences from the usual. We trust you’ll understand, and we look forward to when these pages, and our lives, reach a new equilibrium. It is with great sadness that we note the passing of Stereophile deputy editor Art Dudley. He was one of the finest men ever to grace the audio industry. My tribute to him is in these pages. Also in this issue: Rich Isaacs begins a series on Italian progressive rock with a look at the great PFM (Premiata Forneria Marconi). Ken Sander takes us on a wild rock and roll ride with Eric Burdon and War. Professor Larry Schenbeck continues his series on immersive sound. WL Woodward gets jazzed about bass. John Seetoo concludes his series on legendary Yellow Magic Orchestra/film composer/techno-pop pioneer Ryuichi Sakamoto. In a special report we ask audio companies how they’re responding to the COVID-19 crisis.