Evolving with Your Company [Entire Talk]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ghost Dancer Aka: Dance of Death

Ghost Dancer aka: Dance of Death John Case Ballantine Books ASIN: B000JMKNA6 For Paco Ignacio Taibo, Justo Vasco, and the Semana Negra crew PROLOGUE LIBERIA | SEPTEMBER 2003 There was this…ping. A single, solitary noise that announced itself in the key of C—ping!—and that was that. The noise came from somewhere in the back, at the rear of the fuselage, and for a moment it reminded Mike Burke of his brother’s wedding. It was the sound his father made at the rehearsal dinner, announcing a toast by tapping his glass with a spoon. Ping! It was funny, if you thought about it. But that wasn’t it. Though the helicopter was French (in fact, a single-rotor Ecureuil B2), it was not equipped with champagne flutes. The sound signaled something else, like the noise a tail rotor makes when one of its blades is struck with a 9mm round—and snaps in half and flies away. Or so Burke imagined. Ping! Frowning, he turned to the pilot, a Kiwi named Rubini. “Did you—?” The handsome New Zealander grinned. “No worries, bugalugs!” Suddenly, the chopper yawed violently to starboard, roaring into a slide and twisting down. Rubini’s face went white and he lunged at the controls. Burke gasped, grabbing the armrests on his seat. In an instant, his life—his whole life—passed before his eyes against a veering background of forest and sky. One by one, a thousand scenes played out as the helicopter tobogganed down an invisible staircase toward a wall of trees. In the few seconds it took to fall five hundred feet, Burke remembered every pet he’d ever had, every girl he’d kissed, every house apartment teacher friend and landscape he’d ever seen. -

Redox DAS Artist List for Period

Page: Redox D.A.S. Artist List for01.10.2020 period: - 31.10.2020 Date time: Title: Artist: min:sec 01.10.2020 00:01:07 A WALK IN THE PARK NICK STRAKER BAND 00:03:44 01.10.2020 00:04:58 GEORGY GIRL BOBBY VINTON 00:02:13 01.10.2020 00:07:11 BOOGIE WOOGIE DANCIN SHOES CLAUDIAMAXI BARRY 00:04:52 01.10.2020 00:12:03 GLEJ LJUBEZEN KINGSTON 00:03:45 01.10.2020 00:15:46 CUBA GIBSON BROTHERS 00:07:15 01.10.2020 00:22:59 BAD GIRLS RADIORAMA 00:04:18 01.10.2020 00:27:17 ČE NE BOŠ PROBU NIPKE 00:02:56 01.10.2020 00:30:14 TO LETO BO MOJE MAX FEAT JAN PLESTENJAK IN EVA BOTO00:03:56 01.10.2020 00:34:08 I WILL FOLLOW YOU BOYS NEXT DOOR 00:04:34 01.10.2020 00:38:37 FEELS CALVIN HARRIS FEAT PHARRELL WILLIAMS00:03:40 AND KATY PERRY AND BIG 01.10.2020 00:42:18 TATTOO BIG FOOT MAMA 00:05:21 01.10.2020 00:47:39 WHEN SANDRO SMILES JANETTE CRISCUOLI 00:03:16 01.10.2020 00:50:56 LITER CVIČKA MIRAN RUDAN 00:03:03 01.10.2020 00:54:00 CARELESS WHISPER WHAM FEAT GEORGE MICHAEL 00:04:53 01.10.2020 00:58:49 WATERMELON SUGAR HARRY STYLES 00:02:52 01.10.2020 01:01:41 ŠE IMAM TE RAD NUDE 00:03:56 01.10.2020 03:21:24 NO ORDINARY WORLD JOE COCKER 00:03:44 01.10.2020 03:25:07 VARAJ ME VARAJ SANJA GROHAR 00:02:44 01.10.2020 03:27:51 I LOVE YOU YOU LOVE ME ANTHONY QUINN 00:02:32 01.10.2020 03:30:22 KO LISTJE ODPADLO BO MIRAN RUDAN 00:03:02 01.10.2020 03:33:24 POROPOMPERO CRYSTAL GRASS 00:04:10 01.10.2020 03:37:31 MOJE ORGLICE JANKO ROPRET 00:03:22 01.10.2020 03:41:01 WARRIOR RADIORAMA 00:04:15 01.10.2020 03:45:16 LUNA POWER DANCERS 00:03:36 01.10.2020 03:48:52 HANDS UP / -

Read an Excerpt

Blackout THE L IFE AND SORDID TIMES OF BOBBY TRAVIS Edgar Swamp Special thanks to my sister Gina Kelliher for reading an early draft of this novel and giving me valuable feedback. To show my appreciation, I named one of my characters after her, a dubious honor indeed! I Called the Cops on You Lyrics by Jeremy Quint, Copyright 1992, Basement Tapes Music LTD Copyright © 2017 Edgar Swamp All rights reserved. ISBN: 0692832440 ISBN 13: 9780692832448 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017900492 Edgar Swamp, Carlsbad, CA This book is dedicated to the loving memory of Ms. Ruby, who unfortunately passed before I finished the book. I love you, honey. RIP, 2006–2016. This book is a work of fiction. All names, places, characters etc. are fig- ments of the author’s imagination and are not to be misconstrued as real. Any semblance to anyone living or dead is a coincidence. Foreword This book is not autobiographical; all of the characters are figments of my imagination and are in no way meant to be construed as real people (see disclaimer on the previous page). And by way of explanation, I’d like to of- fer here a brief story that inspired this novel, at least the crux of it anyway, involving a person who blacks out repeatedly hence making anything in life possible at any time. The year was 1993, and I was working at a bar and grill called Rosie’s Water Works in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. I was on my two weeks’ notice, planning to leave the city for Raleigh, North Carolina, in pur- suit of my musical ambitions. -

Redox DAS Artist List for Period: 01.12.2020

Page: Redox D.A.S. Artist List for01.12.2020 period: - 31.12.2020 Date time: Title: Artist: min:sec 01.12.2020 00:06:24 HAVE A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS JOHNNY MATHIS 00:01:57 01.12.2020 00:08:31 BURNING UP MADONNA 00:03:39 01.12.2020 00:12:10 ZLOMLJENO SRCE PIKA BOŽIČ KONTREC 00:03:43 01.12.2020 00:16:13 DON T PAY THE FERRYMAN CHRIS DE BURGH 00:03:24 01.12.2020 00:19:35 NELL ARIA MARCELLA BELLA 00:03:48 01.12.2020 00:23:25 POVEJ NAGLAS ANDREJ IKICA 00:03:13 01.12.2020 00:26:45 LOVE ASHLEE SIMPSON 00:02:31 01.12.2020 00:29:17 SWEET CAROLINA NEIL DIAMOND 00:03:19 01.12.2020 00:32:34 AMAZONKA SAŠKA SMODEJ 00:03:03 01.12.2020 00:35:37 POP N SYNC 00:02:54 01.12.2020 00:38:37 PUTTING ON THE RITZ TACO 00:03:18 01.12.2020 00:41:55 PLOVEMO TRETJI KANU 00:04:30 01.12.2020 00:46:23 TOUCH LITTLE MIX 00:03:28 01.12.2020 00:49:57 EXTENDED DREAM SPAGNA 00:05:44 01.12.2020 00:55:40 THAT S THE TRUTH MCFLY 00:03:48 01.12.2020 00:59:28 MOMENTS IN LOVE BO ANDERSEN AND BERNIE PAUL00:04:27 01.12.2020 01:04:16 NAPOVEDNIK krajše 7 NOČ 00:02:29 01.12.2020 01:04:24 1 DEL 7 NOČ 00:00:43 01.12.2020 01:04:59 OBLADI OBLADA ORG MARMALADE 00:02:59 01.12.2020 01:07:54 VMESNI 2 7 NOČ 00:00:44 01.12.2020 01:07:59 ANOTHER SATURDAY NIGHT SAM COOKE 00:02:38 01.12.2020 01:10:36 PRIDI DALA TI BOM CVET EVA SRŠEN 00:02:50 01.12.2020 01:13:27 VMESNI 2 7 NOČ 00:00:44 01.12.2020 01:13:31 THAT S AMORE DEAN MARTIN FEAT FRANK SINATRA00:03:06 01.12.2020 01:16:38 2 DEL 7 NOČ 00:00:49 01.12.2020 01:17:27 MY WAY FRANK SINATRA 00:04:35 01.12.2020 01:21:55 VMESNI 2 7 NOČ 00:00:44 01.12.2020 -

Double Blind Transcript

RELEVE DES DIALOGUES DOUBLE BLIND un film de SOPHIE CALLE et GREG SHEPHARD SOPHIE voix off : I met him in a bar in December 1989. I was in New York for two days on my way from Mexico to Paris. He offered me a place to stay. Upon accepting, he handed me the address, the keys and he disappeared. He returned two days later. I thanked him and left. The only thing I learned about him was from a piece of paper I found under the cigarette box. It said: “ Resolutions for the new year: no lying, no biting. ” A few days later, I called him from France. After several conversations, we decided to meet in Paris and made an appointment for January 20th, 1990, Orly airport, 10 am. He never arrived, never called, never answered the phone. On January 10th 1991, I received the following phone call: “ It’s Greg Shephard. I am at Orly airport, one year late. Would you like to see me? ” This man knew how to talk to me. That’s how it all began. A year later, I am in New York again. This time to cross America with him and make a video along the way. The plan is to drive his old Cadillac to California where I will teach for a semester. We were to leave January 1st, a few days after my arrival. But instead of meeting me at the airport, I found him asleep in his appartment. He hadn’t left for a week. Nothing had been done. The car was not ready, the cameras not purchased, he had lost his driving license, not said goodbye to his friends, not cleaned the trunk, any excuse would do. -

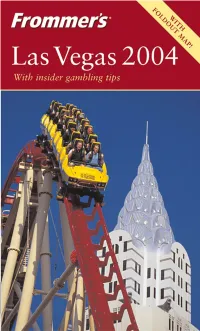

Frommer's Las Vegas 2004

Las Vegas 2004 by Mary Herczog Here’s what the critics say about Frommer’s: “Amazingly easy to use. Very portable, very complete.” —Booklist “Detailed, accurate, and easy-to-read information for all price ranges.” —Glamour Magazine “Hotel information is close to encyclopedic.” —Des Moines Sunday Register “Frommer’s Guides have a way of giving you a real feel for a place.” —Knight Ridder Newspapers About the Author Mary Herczog lives in Los Angeles and works in the film industry. She is the author of Frommer’s New Orleans, California For Dummies, Frommer’s Portable Las Vegas for Non-Gamblers, and Las Vegas For Dummies, and has contributed to Frommer’s Los Angeles. She still isn’t sure when to hit and when to hold in blackjack. Published by: Wiley Publishing, Inc. 111 River St. Hoboken, NJ 07030 Copyright © 2004 Wiley Publishing, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or trans- mitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, record- ing, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8700. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Legal Department, Wiley Publishing, Inc., 10475 Crosspoint Blvd. Indianapolis, IN 46256, (317) 572-3447, fax (317) 572-4447, E-Mail: [email protected]. -

The Vamps: Our Story: 100% Official Free

FREE THE VAMPS: OUR STORY: 100% OFFICIAL PDF The Vamps | 224 pages | 20 Oct 2016 | Headline Publishing Group | 9781472240439 | English | London, United Kingdom The Vamps: Our Story: % Official by The Vamps - Books - Hachette Australia From life on the road to dealing with their new-found fame, nothing is off-limits. Featuring exclusive behind-the-scenes photography, this is a fully- illustrated joint autobiography: the perfect book for any Vamps fan. At least, according to the stories I've been told Because in some bloodsucker storiesvamps change shapes—from semihumans to bats, to wolves, etc. That's why we begin with the vamps —yes, those cruel women; yet not all that cruel, always. In many ways, the principal story of the epic hinges on the envy of Kaikeyi, whose role is much like the vamps of Bollywood cinema, though Kaikeyi is never known If Kaikeyi is cited as often is the case as having some ancestral source of inspiration to the vamps of our time, 5 - That Other Self: The Vamps. The brother every vamp wishes This sexy human being ought to participate on this phenomenon story. The vamp who has very In light of his removal from the field of battle, we are reconsidering our options, and then the master's Enforcer appears, well weaponed. How fortuitous. I knew that The Vamps: Our Story: 100% Official. Thus the story about which Montgomery brother Erica would pick was irritating : It went once too often to the well of Erica as irresistible. But the queen of vamps as far as acting talent goesand therebygoing by the importance in the story given to her A story about my favorite printmy story would be out of date. -

Www .Maver Ic K

JANUARY/FeBRUARY 2014 www.maverick-country.com MAVERICK FROM THE EDITOR... MEET THE TEAM Editor t is with a great deal of sadness, that I acknowlege that this will be my last issue as Alan Cackett editor of Maverick. I have always believed that when you no longer enjoy doing 24 Bray Gardens, Loose, Maidstone, Kent, ME15 9TR, UK something, then it’s time to stop and look to do something di erent. I have had a 01622 744481 Igood run as editor, and now is the time to hand over to someone younger. Someone who [email protected] can hopefully take the magazine forward, embracing country music’s future whilst not Managing Editor overlooking its huge legacy of the past. I know that the new editor Laura Bethell who Michelle Teeman 01622 823920 worked with me for 5 years, 2 as my deputy editor, will do just that. [email protected] It was just over 47 years ago that I edited and published Britain’s rst regular monthly country music magazine. Looking back that was quite an audacious and bold undertaking Designer Laura Bethell for a teenager from a council house estate who le school at 15. Some of the original 01622 823922 readers of Country Music Monthly are still around and have continued to follow my writing [email protected] and views on the music as readers of Maverick. ere was a time when I not only knew Editorial Assistant many of the Maverick readers’ names but had a personal contact with them, but recently Chris Beck I’ve lost touch and I have to say that I miss the chats that we used to have when they phoned Project Manager up to renew their subscriptions. -

The Vamps: Fuori Il Singolo "Married in Vegas

VENERDì 31 LUGLIO 2020 The Vamps ritornano con "Married In Vegas", il nuovo singolo dal 31 luglio su tutte le piattaforme digitali. Il brano anticipa l'album, "Cherry Blossom", in arrivo il prossimo 16 ottobre. The Vamps: Fuori il singolo "Married in Vegas" anticipa l'album "Married In Vegas", segna una nuova era, una vera e propria rinascita per in uscita ad ottobre la band inglese. Brad, Connor, Tristan e James hanno scritto il loro album più personale. Il singolo è stato composto durante l'isolamento da Brad, leader della band e dal produttore Lostboy. "Il giorno in cui abbiamo consegnato l'album ho fatto una telefonata via zoom con Lostboy" spiega Brad. "Ci siamo fatti qualche birra e quattro ANTONIO GALLUZZO ore dopo è nata Married in Vegas". Aggiunge James: "Stavo giocando alla playstation quando Brad mi ha chiamato dicendomi ho appena scritto questa canzone! Amo i momenti come questo perché anche quando pensi che qualcosa sia finita tutto può comunque cambiare all'ultimo minuto". Così l'ultima canzone arrivata è stata scelta come singolo, stravolgendo tutti i piani. [email protected] SPETTACOLINEWS.IT The Vamps, alias Brad Simpson, Connor Ball, Tristan Evans e James McVey, hanno debuttato con l'album, "Meet The Vamps", che nel 2014 è entrato al secondo posto della classifica inglese, certificato disco di platino. Da allora hanno pubblicato "Wake up" nel 2015 e "Night&Day", nelle versioni "Night Edition" (che nel 2017 ha raggiunto la vetta delle classifiche con il brano All Night ft. Matoma) e "Day Edition" nel 2018. Dopo un periodo di pausa, l'estate scorsa, insoddisfatti dei risultati delle prime sessioni, i ragazzi hanno iniziato nuovamente a suonare. -

Constructions of Latinidad in Jane the Virgin

RACE, GENDER, AND SEXUALITY: CONSTRUCTIONS OF LATINIDAD IN JANE THE VIRGIN _______________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________________________ by LITZY GALARZA Dr. Cristina Mislán, Thesis Supervisor MAY 2016 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled RACE, GENDER, AND SEXUALITY: CONSTRUCTIONS OF LATINIDAD IN JANE THE VIRGIN presented by Litzy Galarza, a candidate for the degree of master of arts, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Cristina Mislán Professor Alexis A. Callender Professor Cynthia M. Frisby Professor Keith Greenwood DEDICATION Dedico mi tesis a los mios, a mi familia. A todas las personas que amo y siempre me han dado aliento. A mi madre. A mi abuelo Rosendo. A mis dos hermanas que siempre han aguantado my lengua. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge this work would not be possible without the patience, guidance, and unyielding support of my thesis chair and academic mentor Dr. Cristina Mislán. She has been invested in my work and development as a scholar since the infancy of this project and I will be forever grateful for her encouragement. I would also like to thank Dr. Melissa A. Click for her expertise in television studies, her feedback in identifying weaknesses of my study in its early stages, and her guidance in helping me find useful literature for my analysis. I would also like to extend my gratitude to Dr. -

Study Guide and Interview Transcript to Accompany

STUDY GUIDE AND INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT TO ACCOMPANY VIDEO TAPE “PSYCHOTHERAPY WITH THE EXPERTS” FEATURING KENNETH V. HARDY Jon Carlson Diane Kjos Governors State University University Park, IL FAMILY SYSTEMS THERAPY with Kenneth V. Hardy Introduction This video is one in a series portraying the leading theories of psychotherapy and their application. This series presents the predominant theories and how they are practiced. Each video in the series features a leading practitioner and educator in the field of counseling or psychotherapy. The series is unique in that it features real clients with real problems. During the course of the series these clients bring up a number of issues with the therapists. A theory is a framework that helps us understand something or explains how something works. Just as there are many different people and personalities, there are different theories of understanding how people live and how change occurs, each with its own guidelines for understanding and procedures for operation. The primary differences between these theories are related to the relative importance each theory places on cognitive (thinking), behavioral (doing), and affective (feeling) factors. Each theory has devotees who think and act as the theory prescribes in order to help people change their lives. Certain theories explain certain phenomena better than others. The individual counselor or psychotherapist needs to develop his or her own approach to helping others with problems of an emotional, behavioral, or cognitive nature. Specific objectives in therapy include (1) removing, modifying, or retarding existing symptoms, (2) mediating disturbed patterns of behavior, and (3) promoting positive personality growth and development. -

Dueling Divas

COVER STORY ................................................................ 2 The Sentinel FEATURE STORY .............................................................. 3 SPORTS........................................................................ 4 MOVIES ............................................................13 & 22 WORD SEARCH/ LATE LAUGHS/ CABLE GUIDE ...................... 10 COOKING HIGHLIGHTS ................................................... 12 SUDOKU .................................................................... 13 tvweek STARS ON SCREEN/Q&A ............................................... 23 March 26 - April 1, 2017 Dueling divas Bette (Susan Sarandon, “Thelma & Louise,” 1991) and Joan (Jessica Lange, “American Horror Story”) brace for failure in a new episode of “Feud: Bette and Joan,” airing Sunday. Susan Sarandon stars in “Feud: Bette and Joan” Certiied Technicians We service WhatWesell 49 NEW HOME AND OLD HOME SERVICE WORK J.L. Ruth Electric - The Generator KING... Ask for Joe! WHY CHOOSE US? • Prompt Professional Service • All Work Guaranteed • Family Owned and Operated • Insured A/JL Ruth ASK • 49 Years of Experience • Phone Installation & Service ABOUT OUR •Master Electrician & Plumbing • New&O2ldH omesx 3 $ Licenses in All Townships •Appliance Hook-up 200 • ServingEastandWestShores • Install Exhaust Fans, Roof Fans SAVINGS* *Not valid with • Radio and GPS Equipped Trucks & Light Fixtures any other offer •Residential and Commercial •Generator Service Also Available • 100-400 AMP Service Upgrades • We DoItAll!!