Advanced Perl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 4 Programming in Perl

Chapter 4 Programming in Perl 4.1 More on built-in functions in Perl There are many built-in functions in Perl, and even more are available as modules (see section 4.4) that can be downloaded from various Internet places. Some built-in functions have already been used in chapter 3.1 and some of these and some others will be described in more detail here. 4.1.1 split and join (+ qw, x operator, \here docs", .=) 1 #!/usr/bin/perl 2 3 $sequence = ">|SP:Q62671|RATTUS NORVEGICUS|"; 4 5 @parts = split '\|', $sequence; 6 for ( $i = 0; $i < @parts; $i++ ) { 7 print "Substring $i: $parts[$i]\n"; 8 } • split is used to split a string into an array of substrings. The program above will write out Substring 0: > Substring 1: SP:Q62671 Substring 2: RATTUS NORVEGICUS • The first argument of split specifies a regular expression, while the second is the string to be split. • The string is scanned for occurrences of the regexp which are taken to be the boundaries between the sub-strings. 57 58 CHAPTER 4. PROGRAMMING IN PERL • The parts of the string which are matched with the regexp are not included in the substrings. • Also empty substrings are extracted. Note, however that trailing empty strings are removed by default. • Note that the | character needs to be escaped in the example above, since it is a special character in a regexp. • split returns an array and since an array can be assigned to a list we can write: splitfasta.ply 1 #!/usr/bin/perl 2 3 $sequence=">|SP:Q62671|RATTUS NORVEGICUS|"; 4 5 ($marker, $code, $species) = split '\|', $sequence; 6 ($dummy, $acc) = split ':', $code; 7 print "This FastA sequence comes from the species $species\n"; 8 print "and has accession number $acc.\n"; splitfasta.ply • It is not uncommon that we want to write out long pieces of text using many print statements. -

1. Introduction to Structured Programming 2. Functions

UNIT -3Syllabus: Introduction to structured programming, Functions – basics, user defined functions, inter functions communication, Standard functions, Storage classes- auto, register, static, extern,scope rules, arrays to functions, recursive functions, example C programs. String – Basic concepts, String Input / Output functions, arrays of strings, string handling functions, strings to functions, C programming examples. 1. Introduction to structured programming Software engineering is a discipline that is concerned with the construction of robust and reliable computer programs. Just as civil engineers use tried and tested methods for the construction of buildings, software engineers use accepted methods for analyzing a problem to be solved, a blueprint or plan for the design of the solution and a construction method that minimizes the risk of error. The structured programming approach to program design was based on the following method. i. To solve a large problem, break the problem into several pieces and work on each piece separately. ii. To solve each piece, treat it as a new problem that can itself be broken down into smaller problems; iii. Repeat the process with each new piece until each can be solved directly, without further decomposition. 2. Functions - Basics In programming, a function is a segment that groups code to perform a specific task. A C program has at least one function main().Without main() function, there is technically no C program. Types of C functions There are two types of functions in C programming: 1. Library functions 2. User defined functions 1 Library functions Library functions are the in-built function in C programming system. For example: main() - The execution of every C program starts form this main() function. -

![[PDF] Beginning Raku](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0681/pdf-beginning-raku-210681.webp)

[PDF] Beginning Raku

Beginning Raku Arne Sommer Version 1.00, 22.12.2019 Table of Contents Introduction. 1 The Little Print . 1 Reading Tips . 2 Content . 3 1. About Raku. 5 1.1. Rakudo. 5 1.2. Running Raku in the browser . 6 1.3. REPL. 6 1.4. One Liners . 8 1.5. Running Programs . 9 1.6. Error messages . 9 1.7. use v6. 10 1.8. Documentation . 10 1.9. More Information. 13 1.10. Speed . 13 2. Variables, Operators, Values and Procedures. 15 2.1. Output with say and print . 15 2.2. Variables . 15 2.3. Comments. 17 2.4. Non-destructive operators . 18 2.5. Numerical Operators . 19 2.6. Operator Precedence . 20 2.7. Values . 22 2.8. Variable Names . 24 2.9. constant. 26 2.10. Sigilless variables . 26 2.11. True and False. 27 2.12. // . 29 3. The Type System. 31 3.1. Strong Typing . 31 3.2. ^mro (Method Resolution Order) . 33 3.3. Everything is an Object . 34 3.4. Special Values . 36 3.5. :D (Defined Adverb) . 38 3.6. Type Conversion . 39 3.7. Comparison Operators . 42 4. Control Flow . 47 4.1. Blocks. 47 4.2. Ranges (A Short Introduction). 47 4.3. loop . 48 4.4. for . 49 4.5. Infinite Loops. 53 4.6. while . 53 4.7. until . 54 4.8. repeat while . 55 4.9. repeat until. 55 4.10. Loop Summary . 56 4.11. if . .. -

Eloquent Javascript © 2011 by Marijn Haverbeke Here, Square Is the Name of the Function

2 FUNCTIONS We have already used several functions in the previous chapter—things such as alert and print—to order the machine to perform a specific operation. In this chap- ter, we will start creating our own functions, making it possible to extend the vocabulary that we have avail- able. In a way, this resembles defining our own words inside a story we are writing to increase our expressive- ness. Although such a thing is considered rather bad style in prose, in programming it is indispensable. The Anatomy of a Function Definition In its most basic form, a function definition looks like this: function square(x) { return x * x; } square(12); ! 144 Eloquent JavaScript © 2011 by Marijn Haverbeke Here, square is the name of the function. x is the name of its (first and only) argument. return x * x; is the body of the function. The keyword function is always used when creating a new function. When it is followed by a variable name, the new function will be stored under this name. After the name comes a list of argument names and finally the body of the function. Unlike those around the body of while loops or if state- ments, the braces around a function body are obligatory. The keyword return, followed by an expression, is used to determine the value the function returns. When control comes across a return statement, it immediately jumps out of the current function and gives the returned value to the code that called the function. A return statement without an expres- sion after it will cause the function to return undefined. -

Control Flow, Functions

UNIT III CONTROL FLOW, FUNCTIONS 9 Conditionals: Boolean values and operators, conditional (if), alternative (if-else), chained conditional (if-elif-else); Iteration: state, while, for, break, continue, pass; Fruitful functions: return values, parameters, local and global scope, function composition, recursion; Strings: string slices, immutability, string functions and methods, string module; Lists as arrays. Illustrative programs: square root, gcd, exponentiation, sum an array of numbers, linear search, binary search. UNIT 3 Conditionals: Boolean values: Boolean values are the two constant objects False and True. They are used to represent truth values (although other values can also be considered false or true). In numeric contexts (for example when used as the argument to an arithmetic operator), they behave like the integers 0 and 1, respectively. A string in Python can be tested for truth value. The return type will be in Boolean value (True or False) To see what the return value (True or False) will be, simply print it out. str="Hello World" print str.isalnum() #False #check if all char are numbers print str.isalpha() #False #check if all char in the string are alphabetic print str.isdigit() #False #test if string contains digits print str.istitle() #True #test if string contains title words print str.isupper() #False #test if string contains upper case print str.islower() #False #test if string contains lower case print str.isspace() #False #test if string contains spaces print str.endswith('d') #True #test if string endswith a d print str.startswith('H') #True #test if string startswith H The if statement Conditional statements give us this ability to check the conditions. -

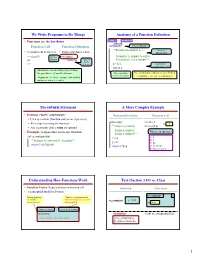

The Return Statement a More Complex Example

We Write Programs to Do Things Anatomy of a Function Definition • Functions are the key doers name parameters Function Call Function Definition def plus(n): Function Header """Returns the number n+1 Docstring • Command to do the function • Defines what function does Specification >>> plus(23) Function def plus(n): Parameter n: number to add to 24 Header return n+1 Function Precondition: n is a number""" Body >>> (indented) x = n+1 Statements to execute when called return x • Parameter: variable that is listed within the parentheses of a method header. The vertical line Use vertical lines when you write Python indicates indentation on exams so we can see indentation • Argument: a value to assign to the method parameter when it is called The return Statement A More Complex Example • Format: return <expression> Function Definition Function Call § Used to evaluate function call (as an expression) def foo(a,b): >>> x = 2 § Also stops executing the function! x ? """Return something >>> foo(3,4) § Any statements after a return are ignored Param a: number • Example: temperature converter function What is in the box? Param b: number""" def to_centigrade(x): x = a A: 2 """Returns: x converted to centigrade""" B: 3 y = b C: 16 return 5*(x-32)/9.0 return x*y+y D: Nothing! E: I do not know Understanding How Functions Work Text (Section 3.10) vs. Class • Function Frame: Representation of function call Textbook This Class • A conceptual model of Python to_centigrade 1 Draw parameters • Number of statement in the as variables function body to execute next to_centigrade x –> 50.0 (named boxes) • Starts with 1 x 50.0 function name instruction counter parameters Definition: Call: to_centigrade(50.0) local variables (later in lecture) def to_centigrade(x): return 5*(x-32)/9.0 1 Example: to_centigrade(50.0) Example: to_centigrade(50.0) 1. -

EN-Google Hacks.Pdf

Table of Contents Credits Foreword Preface Chapter 1. Searching Google 1. Setting Preferences 2. Language Tools 3. Anatomy of a Search Result 4. Specialized Vocabularies: Slang and Terminology 5. Getting Around the 10 Word Limit 6. Word Order Matters 7. Repetition Matters 8. Mixing Syntaxes 9. Hacking Google URLs 10. Hacking Google Search Forms 11. Date-Range Searching 12. Understanding and Using Julian Dates 13. Using Full-Word Wildcards 14. inurl: Versus site: 15. Checking Spelling 16. Consulting the Dictionary 17. Consulting the Phonebook 18. Tracking Stocks 19. Google Interface for Translators 20. Searching Article Archives 21. Finding Directories of Information 22. Finding Technical Definitions 23. Finding Weblog Commentary 24. The Google Toolbar 25. The Mozilla Google Toolbar 26. The Quick Search Toolbar 27. GAPIS 28. Googling with Bookmarklets Chapter 2. Google Special Services and Collections 29. Google Directory 30. Google Groups 31. Google Images 32. Google News 33. Google Catalogs 34. Froogle 35. Google Labs Chapter 3. Third-Party Google Services 36. XooMLe: The Google API in Plain Old XML 37. Google by Email 38. Simplifying Google Groups URLs 39. What Does Google Think Of... 40. GooglePeople Chapter 4. Non-API Google Applications 41. Don't Try This at Home 42. Building a Custom Date-Range Search Form 43. Building Google Directory URLs 44. Scraping Google Results 45. Scraping Google AdWords 46. Scraping Google Groups 47. Scraping Google News 48. Scraping Google Catalogs 49. Scraping the Google Phonebook Chapter 5. Introducing the Google Web API 50. Programming the Google Web API with Perl 51. Looping Around the 10-Result Limit 52. -

Name Description

Perl version 5.10.0 documentation - perlnewmod NAME perlnewmod - preparing a new module for distribution DESCRIPTION This document gives you some suggestions about how to go about writingPerl modules, preparing them for distribution, and making them availablevia CPAN. One of the things that makes Perl really powerful is the fact that Perlhackers tend to want to share the solutions to problems they've faced,so you and I don't have to battle with the same problem again. The main way they do this is by abstracting the solution into a Perlmodule. If you don't know what one of these is, the rest of thisdocument isn't going to be much use to you. You're also missing out onan awful lot of useful code; consider having a look at perlmod, perlmodlib and perlmodinstall before coming back here. When you've found that there isn't a module available for what you'retrying to do, and you've had to write the code yourself, considerpackaging up the solution into a module and uploading it to CPAN so thatothers can benefit. Warning We're going to primarily concentrate on Perl-only modules here, ratherthan XS modules. XS modules serve a rather different purpose, andyou should consider different things before distributing them - thepopularity of the library you are gluing, the portability to otheroperating systems, and so on. However, the notes on preparing the Perlside of the module and packaging and distributing it will apply equallywell to an XS module as a pure-Perl one. What should I make into a module? You should make a module out of any code that you think is going to beuseful to others. -

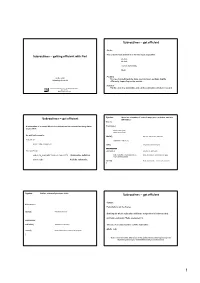

Subroutines – Get Efficient

Subroutines – get efficient So far: The code we have looked at so far has been sequential: Subroutines – getting efficient with Perl do this; do that; now do something; finish; Problem Bela Tiwari You need something to be done over and over, perhaps slightly [email protected] differently depending on the context Solution Environmental Genomics Thematic Programme Put the code in a subroutine and call the subroutine whenever needed. Data Centre http://envgen.nox.ac.uk Syntax: There are a number of correct ways you can define and use Subroutines – get efficient subroutines. One is: A subroutine is a named block of code that can be executed as many times #!/usr/bin/perl as you wish. some code here; some more here; An artificial example: lalala(); #declare and call the subroutine Instead of: a bit more code here; print “Hello everyone!”; exit(); #explicitly exit the program ############ You could use: sub lalala { #define the subroutine sub hello_sub { print "Hello everyone!\n“; } #subroutine definition code to define what lalala does; #code defining the functionality of lalala more defining lalala; &hello_sub; #call the subroutine return(); #end of subroutine – return to the program } Syntax: Outline review of previous slide: Subroutines – get efficient Syntax: #!/usr/bin/perl Permutations on the theme: lalala(); #call the subroutine Defining the whole subroutine within the script when it is first needed: sub hello_sub {print “Hello everyone\n”;} ########### sub lalala { #define the subroutine The use of an ampersand to call the subroutine: &hello_sub; return(); #end of subroutine – return to the program } Note: There are subtle differences in the syntax allowed and required by Perl depending on how you declare/define/call your subroutines. -

Coleman-Coding-Freedom.Pdf

Coding Freedom !" Coding Freedom THE ETHICS AND AESTHETICS OF HACKING !" E. GABRIELLA COLEMAN PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON AND OXFORD Copyright © 2013 by Princeton University Press Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial- NoDerivs CC BY- NC- ND Requests for permission to modify material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW press.princeton.edu All Rights Reserved At the time of writing of this book, the references to Internet Web sites (URLs) were accurate. Neither the author nor Princeton University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Coleman, E. Gabriella, 1973– Coding freedom : the ethics and aesthetics of hacking / E. Gabriella Coleman. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-691-14460-3 (hbk. : alk. paper)—ISBN 978-0-691-14461-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Computer hackers. 2. Computer programmers. 3. Computer programming—Moral and ethical aspects. 4. Computer programming—Social aspects. 5. Intellectual freedom. I. Title. HD8039.D37C65 2012 174’.90051--dc23 2012031422 British Library Cataloging- in- Publication Data is available This book has been composed in Sabon Printed on acid- free paper. ∞ Printed in the United States of America 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 This book is distributed in the hope that it will be useful, but WITHOUT ANY WARRANTY; without even the implied warranty of MERCHANTABILITY or FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE !" We must be free not because we claim freedom, but because we practice it. -

PHP: Constructs and Variables Introduction This Document Describes: 1

PHP: Constructs and Variables Introduction This document describes: 1. the syntax and types of variables, 2. PHP control structures (i.e., conditionals and loops), 3. mixed-mode processing, 4. how to use one script from within another, 5. how to define and use functions, 6. global variables in PHP, 7. special cases for variable types, 8. variable variables, 9. global variables unique to PHP, 10. constants in PHP, 11. arrays (indexed and associative), Brief overview of variables The syntax for PHP variables is similar to C and most other programming languages. There are three primary differences: 1. Variable names must be preceded by a dollar sign ($). 2. Variables do not need to be declared before being used. 3. Variables are dynamically typed, so you do not need to specify the type (e.g., int, float, etc.). Here are the fundamental variable types, which will be covered in more detail later in this document: • Numeric 31 o integer. Integers (±2 ); values outside this range are converted to floating-point. o float. Floating-point numbers. o boolean. true or false; PHP internally resolves these to 1 (one) and 0 (zero) respectively. Also as in C, 0 (zero) is false and anything else is true. • string. String of characters. • array. An array of values, possibly other arrays. Arrays can be indexed or associative (i.e., a hash map). • object. Similar to a class in C++ or Java. (NOTE: Object-oriented PHP programming will not be covered in this course.) • resource. A handle to something that is not PHP data (e.g., image data, database query result). -

Control Flow Statements

Control Flow Statements http://docs.oracle.com/javase/tutorial/java/nutsandbolts/flow.html http://math.hws.edu/javanotes/c3/index.html 1 Control Flow The basic building blocks of programs - variables, expressions, statements, etc. - can be put together to build complex programs with more interesting behavior. CONTROL FLOW STATEMENTS break up the flow of execution by employing decision making, looping, and branching, enabling your program to conditionally execute particular blocks of code. Decision-making statements include the if statements and switch statements. There are also looping statements, as well as branching statements supported by Java. 2 Decision-Making Statements A. if statement if (x > 0) y++; // execute this statement if the expression (x > 0) evaluates to “true” // if it doesn’t evaluate to “true”, this part is just skipped // and the code continues on with the subsequent lines B. if-else statement - - gives another option if the expression by the if part evaluates to “false” if (x > 0) y++; // execute this statement if the expression (x > 0) evaluates to “true” else z++; // if expression doesn’t evaluate to “true”, then this part is executed instead if (testScore >= 90) grade = ‘A’; else if (testScore >= 80) grade = ‘B’; else if (testScore >= 70) grade = ‘C’; else if (testScore >= 60) grade = ‘D’; else grade = ‘F’; C. switch statement - - can be used in place of a big if-then-else statement; works with primitive types byte, short, char, and int; also with Strings, with Java SE7, (enclose the String with double quotes);