Eloquent Javascript © 2011 by Marijn Haverbeke Here, Square Is the Name of the Function

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 4 Programming in Perl

Chapter 4 Programming in Perl 4.1 More on built-in functions in Perl There are many built-in functions in Perl, and even more are available as modules (see section 4.4) that can be downloaded from various Internet places. Some built-in functions have already been used in chapter 3.1 and some of these and some others will be described in more detail here. 4.1.1 split and join (+ qw, x operator, \here docs", .=) 1 #!/usr/bin/perl 2 3 $sequence = ">|SP:Q62671|RATTUS NORVEGICUS|"; 4 5 @parts = split '\|', $sequence; 6 for ( $i = 0; $i < @parts; $i++ ) { 7 print "Substring $i: $parts[$i]\n"; 8 } • split is used to split a string into an array of substrings. The program above will write out Substring 0: > Substring 1: SP:Q62671 Substring 2: RATTUS NORVEGICUS • The first argument of split specifies a regular expression, while the second is the string to be split. • The string is scanned for occurrences of the regexp which are taken to be the boundaries between the sub-strings. 57 58 CHAPTER 4. PROGRAMMING IN PERL • The parts of the string which are matched with the regexp are not included in the substrings. • Also empty substrings are extracted. Note, however that trailing empty strings are removed by default. • Note that the | character needs to be escaped in the example above, since it is a special character in a regexp. • split returns an array and since an array can be assigned to a list we can write: splitfasta.ply 1 #!/usr/bin/perl 2 3 $sequence=">|SP:Q62671|RATTUS NORVEGICUS|"; 4 5 ($marker, $code, $species) = split '\|', $sequence; 6 ($dummy, $acc) = split ':', $code; 7 print "This FastA sequence comes from the species $species\n"; 8 print "and has accession number $acc.\n"; splitfasta.ply • It is not uncommon that we want to write out long pieces of text using many print statements. -

1. Introduction to Structured Programming 2. Functions

UNIT -3Syllabus: Introduction to structured programming, Functions – basics, user defined functions, inter functions communication, Standard functions, Storage classes- auto, register, static, extern,scope rules, arrays to functions, recursive functions, example C programs. String – Basic concepts, String Input / Output functions, arrays of strings, string handling functions, strings to functions, C programming examples. 1. Introduction to structured programming Software engineering is a discipline that is concerned with the construction of robust and reliable computer programs. Just as civil engineers use tried and tested methods for the construction of buildings, software engineers use accepted methods for analyzing a problem to be solved, a blueprint or plan for the design of the solution and a construction method that minimizes the risk of error. The structured programming approach to program design was based on the following method. i. To solve a large problem, break the problem into several pieces and work on each piece separately. ii. To solve each piece, treat it as a new problem that can itself be broken down into smaller problems; iii. Repeat the process with each new piece until each can be solved directly, without further decomposition. 2. Functions - Basics In programming, a function is a segment that groups code to perform a specific task. A C program has at least one function main().Without main() function, there is technically no C program. Types of C functions There are two types of functions in C programming: 1. Library functions 2. User defined functions 1 Library functions Library functions are the in-built function in C programming system. For example: main() - The execution of every C program starts form this main() function. -

Control Flow, Functions

UNIT III CONTROL FLOW, FUNCTIONS 9 Conditionals: Boolean values and operators, conditional (if), alternative (if-else), chained conditional (if-elif-else); Iteration: state, while, for, break, continue, pass; Fruitful functions: return values, parameters, local and global scope, function composition, recursion; Strings: string slices, immutability, string functions and methods, string module; Lists as arrays. Illustrative programs: square root, gcd, exponentiation, sum an array of numbers, linear search, binary search. UNIT 3 Conditionals: Boolean values: Boolean values are the two constant objects False and True. They are used to represent truth values (although other values can also be considered false or true). In numeric contexts (for example when used as the argument to an arithmetic operator), they behave like the integers 0 and 1, respectively. A string in Python can be tested for truth value. The return type will be in Boolean value (True or False) To see what the return value (True or False) will be, simply print it out. str="Hello World" print str.isalnum() #False #check if all char are numbers print str.isalpha() #False #check if all char in the string are alphabetic print str.isdigit() #False #test if string contains digits print str.istitle() #True #test if string contains title words print str.isupper() #False #test if string contains upper case print str.islower() #False #test if string contains lower case print str.isspace() #False #test if string contains spaces print str.endswith('d') #True #test if string endswith a d print str.startswith('H') #True #test if string startswith H The if statement Conditional statements give us this ability to check the conditions. -

The Return Statement a More Complex Example

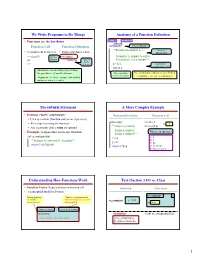

We Write Programs to Do Things Anatomy of a Function Definition • Functions are the key doers name parameters Function Call Function Definition def plus(n): Function Header """Returns the number n+1 Docstring • Command to do the function • Defines what function does Specification >>> plus(23) Function def plus(n): Parameter n: number to add to 24 Header return n+1 Function Precondition: n is a number""" Body >>> (indented) x = n+1 Statements to execute when called return x • Parameter: variable that is listed within the parentheses of a method header. The vertical line Use vertical lines when you write Python indicates indentation on exams so we can see indentation • Argument: a value to assign to the method parameter when it is called The return Statement A More Complex Example • Format: return <expression> Function Definition Function Call § Used to evaluate function call (as an expression) def foo(a,b): >>> x = 2 § Also stops executing the function! x ? """Return something >>> foo(3,4) § Any statements after a return are ignored Param a: number • Example: temperature converter function What is in the box? Param b: number""" def to_centigrade(x): x = a A: 2 """Returns: x converted to centigrade""" B: 3 y = b C: 16 return 5*(x-32)/9.0 return x*y+y D: Nothing! E: I do not know Understanding How Functions Work Text (Section 3.10) vs. Class • Function Frame: Representation of function call Textbook This Class • A conceptual model of Python to_centigrade 1 Draw parameters • Number of statement in the as variables function body to execute next to_centigrade x –> 50.0 (named boxes) • Starts with 1 x 50.0 function name instruction counter parameters Definition: Call: to_centigrade(50.0) local variables (later in lecture) def to_centigrade(x): return 5*(x-32)/9.0 1 Example: to_centigrade(50.0) Example: to_centigrade(50.0) 1. -

Subroutines – Get Efficient

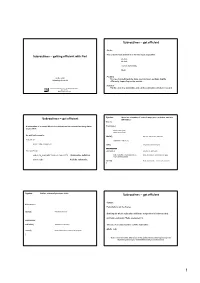

Subroutines – get efficient So far: The code we have looked at so far has been sequential: Subroutines – getting efficient with Perl do this; do that; now do something; finish; Problem Bela Tiwari You need something to be done over and over, perhaps slightly [email protected] differently depending on the context Solution Environmental Genomics Thematic Programme Put the code in a subroutine and call the subroutine whenever needed. Data Centre http://envgen.nox.ac.uk Syntax: There are a number of correct ways you can define and use Subroutines – get efficient subroutines. One is: A subroutine is a named block of code that can be executed as many times #!/usr/bin/perl as you wish. some code here; some more here; An artificial example: lalala(); #declare and call the subroutine Instead of: a bit more code here; print “Hello everyone!”; exit(); #explicitly exit the program ############ You could use: sub lalala { #define the subroutine sub hello_sub { print "Hello everyone!\n“; } #subroutine definition code to define what lalala does; #code defining the functionality of lalala more defining lalala; &hello_sub; #call the subroutine return(); #end of subroutine – return to the program } Syntax: Outline review of previous slide: Subroutines – get efficient Syntax: #!/usr/bin/perl Permutations on the theme: lalala(); #call the subroutine Defining the whole subroutine within the script when it is first needed: sub hello_sub {print “Hello everyone\n”;} ########### sub lalala { #define the subroutine The use of an ampersand to call the subroutine: &hello_sub; return(); #end of subroutine – return to the program } Note: There are subtle differences in the syntax allowed and required by Perl depending on how you declare/define/call your subroutines. -

PHP: Constructs and Variables Introduction This Document Describes: 1

PHP: Constructs and Variables Introduction This document describes: 1. the syntax and types of variables, 2. PHP control structures (i.e., conditionals and loops), 3. mixed-mode processing, 4. how to use one script from within another, 5. how to define and use functions, 6. global variables in PHP, 7. special cases for variable types, 8. variable variables, 9. global variables unique to PHP, 10. constants in PHP, 11. arrays (indexed and associative), Brief overview of variables The syntax for PHP variables is similar to C and most other programming languages. There are three primary differences: 1. Variable names must be preceded by a dollar sign ($). 2. Variables do not need to be declared before being used. 3. Variables are dynamically typed, so you do not need to specify the type (e.g., int, float, etc.). Here are the fundamental variable types, which will be covered in more detail later in this document: • Numeric 31 o integer. Integers (±2 ); values outside this range are converted to floating-point. o float. Floating-point numbers. o boolean. true or false; PHP internally resolves these to 1 (one) and 0 (zero) respectively. Also as in C, 0 (zero) is false and anything else is true. • string. String of characters. • array. An array of values, possibly other arrays. Arrays can be indexed or associative (i.e., a hash map). • object. Similar to a class in C++ or Java. (NOTE: Object-oriented PHP programming will not be covered in this course.) • resource. A handle to something that is not PHP data (e.g., image data, database query result). -

Control Flow Statements

Control Flow Statements http://docs.oracle.com/javase/tutorial/java/nutsandbolts/flow.html http://math.hws.edu/javanotes/c3/index.html 1 Control Flow The basic building blocks of programs - variables, expressions, statements, etc. - can be put together to build complex programs with more interesting behavior. CONTROL FLOW STATEMENTS break up the flow of execution by employing decision making, looping, and branching, enabling your program to conditionally execute particular blocks of code. Decision-making statements include the if statements and switch statements. There are also looping statements, as well as branching statements supported by Java. 2 Decision-Making Statements A. if statement if (x > 0) y++; // execute this statement if the expression (x > 0) evaluates to “true” // if it doesn’t evaluate to “true”, this part is just skipped // and the code continues on with the subsequent lines B. if-else statement - - gives another option if the expression by the if part evaluates to “false” if (x > 0) y++; // execute this statement if the expression (x > 0) evaluates to “true” else z++; // if expression doesn’t evaluate to “true”, then this part is executed instead if (testScore >= 90) grade = ‘A’; else if (testScore >= 80) grade = ‘B’; else if (testScore >= 70) grade = ‘C’; else if (testScore >= 60) grade = ‘D’; else grade = ‘F’; C. switch statement - - can be used in place of a big if-then-else statement; works with primitive types byte, short, char, and int; also with Strings, with Java SE7, (enclose the String with double quotes); -

C Programming Tutorial

C Programming Tutorial C PROGRAMMING TUTORIAL Simply Easy Learning by tutorialspoint.com tutorialspoint.com i COPYRIGHT & DISCLAIMER NOTICE All the content and graphics on this tutorial are the property of tutorialspoint.com. Any content from tutorialspoint.com or this tutorial may not be redistributed or reproduced in any way, shape, or form without the written permission of tutorialspoint.com. Failure to do so is a violation of copyright laws. This tutorial may contain inaccuracies or errors and tutorialspoint provides no guarantee regarding the accuracy of the site or its contents including this tutorial. If you discover that the tutorialspoint.com site or this tutorial content contains some errors, please contact us at [email protected] ii Table of Contents C Language Overview .............................................................. 1 Facts about C ............................................................................................... 1 Why to use C ? ............................................................................................. 2 C Programs .................................................................................................. 2 C Environment Setup ............................................................... 3 Text Editor ................................................................................................... 3 The C Compiler ............................................................................................ 3 Installation on Unix/Linux ............................................................................ -

Codebridge User's Guide Contents • Iii Passing Miscellaneous Information

Micro Focus RM/COBOL CodeBridge User’s Guide Micro Focus The Lawn 22-30 Old Bath Road Newbury, Berkshire RG14 1QN UK http://www.microfocus.com © Copyright 2017-2020 Micro Focus or one of its affiliates. The only warranties for products and services of Micro Focus and its affiliates and licensors (“Micro Focus”) are as may be set forth in the express warranty statements accompanying such products and services. Nothing herein should be construed as constituting an additional warranty. Micro Focus shall not be liable for technical or editorial errors or omissions contained herein. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice. Revised 2020-05-06 for version 12.17 Contents Preface ...................................................................................................... 1 Welcome to CodeBridge ............................................................................................................ 1 Who Should Use CodeBridge .................................................................................................... 1 Organization of Information ...................................................................................................... 2 Related Publications................................................................................................................... 3 Symbols and Conventions .......................................................................................................... 3 Technical Support ..................................................................................................................... -

Introduction to Software Testing Chapter 2.3 Graph Coverage for Source Code

Introduction to Software Testing Chapter 2.3 Graph Coverage for Source Code Paul Ammann & Jeff Offutt www.introsoftwaretesting.com Overview • The most common application of graph criteria is to program source • Graph : Usually the control flow graph (CFG) • Node coverage : Execute every statement • Edge coverage : Execute every branch • Loops : Looping structures such as for loops, while loops, etc. • Data flow coverage : Augment the CFG – defs are statements that assign values to variables – uses are statements that use variables Introduction to Software Testing (Ch 2), www.introsoftwaretesting.com © Ammann & Offutt 2 Control Flow Graphs • A CFG models all executions of a method by describing control structures • Nodes : Statements or sequences of statements (basic blocks) • Edges : Transfers of control • Basic Block : A sequence of statements such that if the first statement is executed, all statements will be (no branches) • CFGs are sometimes annotated with extra information – branch predicates – defs – uses • Rules for translating statements into graphs … Introduction to Software Testing (Ch 2), www.introsoftwaretesting.com © Ammann & Offutt 3 CFG : The if Statement if (x < y) { y = 0; 1 x = x + 1; x < y x >= y } y = 0 2 3 x = y else x = x + 1 { x = y; 4 } if (x < y) 1 { x < y y = 0; y = 0 x >= y 2 x = x + 1; x = x + 1 } 3 Introduction to Software Testing (Ch 2), www.introsoftwaretesting.com © Ammann & Offutt 4 CFG : The if-Return Statement if (x < y) { 1 return; x < y } return x >= y print (x); 2 return; print (x) 3 return No edge from node 2 to 3. The return nodes must be distinct. -

Lesson 5: User Defined Functions and Stack Mechanics Objectives

Lesson 5: User Defined Functions and Stack Mechanics Objectives: (a) Demonstrate the ability to analyze simple programs that use library and user defined functions. (b) Describe the organization and contents of a program’s stack throughout a program’s execution. (c) Demonstrate the ability to examine the stack values of a running program using the debugger. 1. Functions It is often best to solve a large problem by successively decomposing it into smaller and smaller sub-problems. In this manner we introduce and implement functions in C programs. A function is a small subprogram that performs a specific task in a program. Functions promote the writing of efficient programs. If we have large tasks that we want our program to accomplish, we can break it down into small, more manageable subtasks which individual functions can solve. The use of functions makes the C programming language more useful and robust. There are three types of functions that we discuss in this chapter: the main function, library functions and user-defined functions. 1.1 int main ( ) Since we introduced C programs in Chapter 2 we have included the function main in every C program. The main function is a very special function, as it is the only function required in a C program and is the point of entry from which every C program begins executing. The contents of the body of main can vary widely as we have seen from chapter to chapter, but the structure always follows this form: int main () // Main function { variable declarations; // body of main statement 1; (etc., etc.) statement n; } 1.2 Library Functions To date we have seen C programs which consist solely of the main function and/or import C libraries to utilize pre-defined library functions like printf, scanf or strcpy by adding a #include line at the beginning of the program for each C library we draw library functions from. -

Technical Standard COBOL Language

Technical Standard COBOL Language NICAL H S C T A E N T D A R D [This page intentionally left blank] X/Open CAE Specification COBOL Language X/Open Company, Ltd. December 1991, X/Open Company Limited All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owners. X/Open CAE Specification COBOL Language ISBN: 1 872630 09 X X/Open Document Number: XO/CAE/91/200 Set in Palatino by X/Open Company Ltd., U.K. Printed by Maple Press, U.K. Published by X/Open Company Ltd., U.K. Any comments relating to the material contained in this document may be submitted to X/Open at: X/Open Company Limited Apex Plaza Forbury Road Reading Berkshire, RG1 1AX United Kingdom or by Electronic Mail to: [email protected] X/Open CAE Specification (1991) Page : ii COBOL Language Contents COBOL LANGUAGE Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 THE X/OPEN COBOL DEFINITION 1.2 HISTORY OF THIS DOCUMENT 1.3 FORMAT OF ENTRIES 1.3.1 Typographical Conventions 1.3.2 Terminology Chapter 2 COBOL DEFINITION 2.1 GENERAL FORMAT FOR A SEQUENCE OF SOURCE PROGRAMS 2.2 GENERAL FORMAT FOR NESTED SOURCE PROGRAMS 2.2.1 Nested-Source-Program 2.3 GENERAL FORMAT FOR IDENTIFICATION DIVISION 2.4 GENERAL FORMAT FOR ENVIRONMENT DIVISION 2.5 GENERAL FORMAT FOR SOURCE-COMPUTER-ENTRY 2.6 GENERAL FORMAT FOR OBJECT-COMPUTER-ENTRY 2.7 GENERAL FORMAT FOR SPECIAL-NAMES-CONTENT 2.8 GENERAL FORMAT FOR FILE-CONTROL-ENTRY 2.8.1