Control Flow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 4 Programming in Perl

Chapter 4 Programming in Perl 4.1 More on built-in functions in Perl There are many built-in functions in Perl, and even more are available as modules (see section 4.4) that can be downloaded from various Internet places. Some built-in functions have already been used in chapter 3.1 and some of these and some others will be described in more detail here. 4.1.1 split and join (+ qw, x operator, \here docs", .=) 1 #!/usr/bin/perl 2 3 $sequence = ">|SP:Q62671|RATTUS NORVEGICUS|"; 4 5 @parts = split '\|', $sequence; 6 for ( $i = 0; $i < @parts; $i++ ) { 7 print "Substring $i: $parts[$i]\n"; 8 } • split is used to split a string into an array of substrings. The program above will write out Substring 0: > Substring 1: SP:Q62671 Substring 2: RATTUS NORVEGICUS • The first argument of split specifies a regular expression, while the second is the string to be split. • The string is scanned for occurrences of the regexp which are taken to be the boundaries between the sub-strings. 57 58 CHAPTER 4. PROGRAMMING IN PERL • The parts of the string which are matched with the regexp are not included in the substrings. • Also empty substrings are extracted. Note, however that trailing empty strings are removed by default. • Note that the | character needs to be escaped in the example above, since it is a special character in a regexp. • split returns an array and since an array can be assigned to a list we can write: splitfasta.ply 1 #!/usr/bin/perl 2 3 $sequence=">|SP:Q62671|RATTUS NORVEGICUS|"; 4 5 ($marker, $code, $species) = split '\|', $sequence; 6 ($dummy, $acc) = split ':', $code; 7 print "This FastA sequence comes from the species $species\n"; 8 print "and has accession number $acc.\n"; splitfasta.ply • It is not uncommon that we want to write out long pieces of text using many print statements. -

1. Introduction to Structured Programming 2. Functions

UNIT -3Syllabus: Introduction to structured programming, Functions – basics, user defined functions, inter functions communication, Standard functions, Storage classes- auto, register, static, extern,scope rules, arrays to functions, recursive functions, example C programs. String – Basic concepts, String Input / Output functions, arrays of strings, string handling functions, strings to functions, C programming examples. 1. Introduction to structured programming Software engineering is a discipline that is concerned with the construction of robust and reliable computer programs. Just as civil engineers use tried and tested methods for the construction of buildings, software engineers use accepted methods for analyzing a problem to be solved, a blueprint or plan for the design of the solution and a construction method that minimizes the risk of error. The structured programming approach to program design was based on the following method. i. To solve a large problem, break the problem into several pieces and work on each piece separately. ii. To solve each piece, treat it as a new problem that can itself be broken down into smaller problems; iii. Repeat the process with each new piece until each can be solved directly, without further decomposition. 2. Functions - Basics In programming, a function is a segment that groups code to perform a specific task. A C program has at least one function main().Without main() function, there is technically no C program. Types of C functions There are two types of functions in C programming: 1. Library functions 2. User defined functions 1 Library functions Library functions are the in-built function in C programming system. For example: main() - The execution of every C program starts form this main() function. -

7. Control Flow First?

Copyright (C) R.A. van Engelen, FSU Department of Computer Science, 2000-2004 Ordering Program Execution: What is Done 7. Control Flow First? Overview Categories for specifying ordering in programming languages: Expressions 1. Sequencing: the execution of statements and evaluation of Evaluation order expressions is usually in the order in which they appear in a Assignments program text Structured and unstructured flow constructs 2. Selection (or alternation): a run-time condition determines the Goto's choice among two or more statements or expressions Sequencing 3. Iteration: a statement is repeated a number of times or until a Selection run-time condition is met Iteration and iterators 4. Procedural abstraction: subroutines encapsulate collections of Recursion statements and subroutine calls can be treated as single Nondeterminacy statements 5. Recursion: subroutines which call themselves directly or indirectly to solve a problem, where the problem is typically defined in terms of simpler versions of itself 6. Concurrency: two or more program fragments executed in parallel, either on separate processors or interleaved on a single processor Note: Study Chapter 6 of the textbook except Section 7. Nondeterminacy: the execution order among alternative 6.6.2. constructs is deliberately left unspecified, indicating that any alternative will lead to a correct result Expression Syntax Expression Evaluation Ordering: Precedence An expression consists of and Associativity An atomic object, e.g. number or variable The use of infix, prefix, and postfix notation leads to ambiguity An operator applied to a collection of operands (or as to what is an operand of what arguments) which are expressions Fortran example: a+b*c**d**e/f Common syntactic forms for operators: The choice among alternative evaluation orders depends on Function call notation, e.g. -

A Survey of Hardware-Based Control Flow Integrity (CFI)

A survey of Hardware-based Control Flow Integrity (CFI) RUAN DE CLERCQ∗ and INGRID VERBAUWHEDE, KU Leuven Control Flow Integrity (CFI) is a computer security technique that detects runtime attacks by monitoring a program’s branching behavior. This work presents a detailed analysis of the security policies enforced by 21 recent hardware-based CFI architectures. The goal is to evaluate the security, limitations, hardware cost, performance, and practicality of using these policies. We show that many architectures are not suitable for widespread adoption, since they have practical issues, such as relying on accurate control flow model (which is difficult to obtain) or they implement policies which provide only limited security. CCS Concepts: • Security and privacy → Hardware-based security protocols; Information flow control; • General and reference → Surveys and overviews; Additional Key Words and Phrases: control-flow integrity, control-flow hijacking, return oriented programming, shadow stack ACM Reference format: Ruan de Clercq and Ingrid Verbauwhede. YYYY. A survey of Hardware-based Control Flow Integrity (CFI). ACM Comput. Surv. V, N, Article A (January YYYY), 27 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/nnnnnnn.nnnnnnn 1 INTRODUCTION Today, a lot of software is written in memory unsafe languages, such as C and C++, which introduces memory corruption bugs. This makes software vulnerable to attack, since attackers exploit these bugs to make the software misbehave. Modern Operating Systems (OSs) and microprocessors are equipped with security mechanisms to protect against some classes of attacks. However, these mechanisms cannot defend against all attack classes. In particular, Code Reuse Attacks (CRAs), which re-uses pre-existing software for malicious purposes, is an important threat that is difficult to protect against. -

Eloquent Javascript © 2011 by Marijn Haverbeke Here, Square Is the Name of the Function

2 FUNCTIONS We have already used several functions in the previous chapter—things such as alert and print—to order the machine to perform a specific operation. In this chap- ter, we will start creating our own functions, making it possible to extend the vocabulary that we have avail- able. In a way, this resembles defining our own words inside a story we are writing to increase our expressive- ness. Although such a thing is considered rather bad style in prose, in programming it is indispensable. The Anatomy of a Function Definition In its most basic form, a function definition looks like this: function square(x) { return x * x; } square(12); ! 144 Eloquent JavaScript © 2011 by Marijn Haverbeke Here, square is the name of the function. x is the name of its (first and only) argument. return x * x; is the body of the function. The keyword function is always used when creating a new function. When it is followed by a variable name, the new function will be stored under this name. After the name comes a list of argument names and finally the body of the function. Unlike those around the body of while loops or if state- ments, the braces around a function body are obligatory. The keyword return, followed by an expression, is used to determine the value the function returns. When control comes across a return statement, it immediately jumps out of the current function and gives the returned value to the code that called the function. A return statement without an expres- sion after it will cause the function to return undefined. -

Control-Flow Analysis of Functional Programs

Control-flow analysis of functional programs JAN MIDTGAARD Department of Computer Science, Aarhus University We present a survey of control-flow analysis of functional programs, which has been the subject of extensive investigation throughout the past 30 years. Analyses of the control flow of functional programs have been formulated in multiple settings and have led to many different approximations, starting with the seminal works of Jones, Shivers, and Sestoft. In this paper, we survey control-flow analysis of functional programs by structuring the multitude of formulations and approximations and comparing them. Categories and Subject Descriptors: D.3.2 [Programming Languages]: Language Classifica- tions—Applicative languages; F.3.1 [Logics and Meanings of Programs]: Specifying and Ver- ifying and Reasoning about Programs General Terms: Languages, Theory, Verification Additional Key Words and Phrases: Control-flow analysis, higher-order functions 1. INTRODUCTION Since the introduction of high-level languages and compilers, much work has been devoted to approximating, at compile time, which values the variables of a given program may denote at run time. The problem has been named data-flow analysis or just flow analysis. In a language without higher-order functions, the operator of a function call is apparent from the text of the program: it is a lexically visible identifier and therefore the called function is available at compile time. One can thus base an analysis for such a language on the textual structure of the program, since it determines the exact control flow of the program, e.g., as a flow chart. On the other hand, in a language with higher-order functions, the operator of a function call may not be apparent from the text of the program: it can be the result of a computation and therefore the called function may not be available until run time. -

Control Flow, Functions

UNIT III CONTROL FLOW, FUNCTIONS 9 Conditionals: Boolean values and operators, conditional (if), alternative (if-else), chained conditional (if-elif-else); Iteration: state, while, for, break, continue, pass; Fruitful functions: return values, parameters, local and global scope, function composition, recursion; Strings: string slices, immutability, string functions and methods, string module; Lists as arrays. Illustrative programs: square root, gcd, exponentiation, sum an array of numbers, linear search, binary search. UNIT 3 Conditionals: Boolean values: Boolean values are the two constant objects False and True. They are used to represent truth values (although other values can also be considered false or true). In numeric contexts (for example when used as the argument to an arithmetic operator), they behave like the integers 0 and 1, respectively. A string in Python can be tested for truth value. The return type will be in Boolean value (True or False) To see what the return value (True or False) will be, simply print it out. str="Hello World" print str.isalnum() #False #check if all char are numbers print str.isalpha() #False #check if all char in the string are alphabetic print str.isdigit() #False #test if string contains digits print str.istitle() #True #test if string contains title words print str.isupper() #False #test if string contains upper case print str.islower() #False #test if string contains lower case print str.isspace() #False #test if string contains spaces print str.endswith('d') #True #test if string endswith a d print str.startswith('H') #True #test if string startswith H The if statement Conditional statements give us this ability to check the conditions. -

The Return Statement a More Complex Example

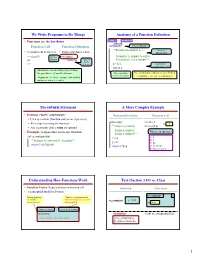

We Write Programs to Do Things Anatomy of a Function Definition • Functions are the key doers name parameters Function Call Function Definition def plus(n): Function Header """Returns the number n+1 Docstring • Command to do the function • Defines what function does Specification >>> plus(23) Function def plus(n): Parameter n: number to add to 24 Header return n+1 Function Precondition: n is a number""" Body >>> (indented) x = n+1 Statements to execute when called return x • Parameter: variable that is listed within the parentheses of a method header. The vertical line Use vertical lines when you write Python indicates indentation on exams so we can see indentation • Argument: a value to assign to the method parameter when it is called The return Statement A More Complex Example • Format: return <expression> Function Definition Function Call § Used to evaluate function call (as an expression) def foo(a,b): >>> x = 2 § Also stops executing the function! x ? """Return something >>> foo(3,4) § Any statements after a return are ignored Param a: number • Example: temperature converter function What is in the box? Param b: number""" def to_centigrade(x): x = a A: 2 """Returns: x converted to centigrade""" B: 3 y = b C: 16 return 5*(x-32)/9.0 return x*y+y D: Nothing! E: I do not know Understanding How Functions Work Text (Section 3.10) vs. Class • Function Frame: Representation of function call Textbook This Class • A conceptual model of Python to_centigrade 1 Draw parameters • Number of statement in the as variables function body to execute next to_centigrade x –> 50.0 (named boxes) • Starts with 1 x 50.0 function name instruction counter parameters Definition: Call: to_centigrade(50.0) local variables (later in lecture) def to_centigrade(x): return 5*(x-32)/9.0 1 Example: to_centigrade(50.0) Example: to_centigrade(50.0) 1. -

Subroutines – Get Efficient

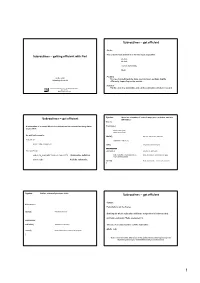

Subroutines – get efficient So far: The code we have looked at so far has been sequential: Subroutines – getting efficient with Perl do this; do that; now do something; finish; Problem Bela Tiwari You need something to be done over and over, perhaps slightly [email protected] differently depending on the context Solution Environmental Genomics Thematic Programme Put the code in a subroutine and call the subroutine whenever needed. Data Centre http://envgen.nox.ac.uk Syntax: There are a number of correct ways you can define and use Subroutines – get efficient subroutines. One is: A subroutine is a named block of code that can be executed as many times #!/usr/bin/perl as you wish. some code here; some more here; An artificial example: lalala(); #declare and call the subroutine Instead of: a bit more code here; print “Hello everyone!”; exit(); #explicitly exit the program ############ You could use: sub lalala { #define the subroutine sub hello_sub { print "Hello everyone!\n“; } #subroutine definition code to define what lalala does; #code defining the functionality of lalala more defining lalala; &hello_sub; #call the subroutine return(); #end of subroutine – return to the program } Syntax: Outline review of previous slide: Subroutines – get efficient Syntax: #!/usr/bin/perl Permutations on the theme: lalala(); #call the subroutine Defining the whole subroutine within the script when it is first needed: sub hello_sub {print “Hello everyone\n”;} ########### sub lalala { #define the subroutine The use of an ampersand to call the subroutine: &hello_sub; return(); #end of subroutine – return to the program } Note: There are subtle differences in the syntax allowed and required by Perl depending on how you declare/define/call your subroutines. -

Obfuscating C++ Programs Via Control Flow Flattening

Annales Univ. Sci. Budapest., Sect. Comp. 30 (2009) 3-19 OBFUSCATING C++ PROGRAMS VIA CONTROL FLOW FLATTENING T. L¶aszl¶oand A.¶ Kiss (Szeged, Hungary) Abstract. Protecting a software from unauthorized access is an ever de- manding task. Thus, in this paper, we focus on the protection of source code by means of obfuscation and discuss the adaptation of a control flow transformation technique called control flow flattening to the C++ lan- guage. In addition to the problems of adaptation and the solutions pro- posed for them, a formal algorithm of the technique is given as well. A prototype implementation of the algorithm presents that the complexity of a program can show an increase as high as 5-fold due to the obfuscation. 1. Introduction Protecting a software from unauthorized access is an ever demanding task. Unfortunately, it is impossible to guarantee complete safety, since with enough time given, there is no unbreakable code. Thus, the goal is usually to make the job of the attacker as di±cult as possible. Systems can be protected at several levels, e.g., hardware, operating system or source code. In this paper, we focus on the protection of source code by means of obfuscation. Several code obfuscation techniques exist. Their common feature is that they change programs to make their comprehension di±cult, while keep- ing their original behaviour. The simplest technique is layout transformation [1], which scrambles identi¯ers in the code, removes comments and debug informa- tion. Another technique is data obfuscation [2], which changes data structures, 4 T. L¶aszl¶oand A.¶ Kiss e.g., by changing variable visibilities or by reordering and restructuring arrays. -

Control Flow Statements

Control Flow Statements Christopher M. Harden Contents 1 Some more types 2 1.1 Undefined and null . .2 1.2 Booleans . .2 1.2.1 Creating boolean values . .3 1.2.2 Combining boolean values . .4 2 Conditional statements 5 2.1 if statement . .5 2.1.1 Using blocks . .5 2.2 else statement . .6 2.3 Tertiary operator . .7 2.4 switch statement . .8 3 Looping constructs 10 3.1 while loop . 10 3.2 do while loop . 11 3.3 for loop . 11 3.4 Further loop control . 12 4 Try it yourself 13 1 1 Some more types 1.1 Undefined and null The undefined type has only one value, undefined. Similarly, the null type has only one value, null. Since both types have only one value, there are no operators on these types. These types exist to represent the absence of data, and their difference is only in intent. • undefined represents data that is accidentally missing. • null represents data that is intentionally missing. In general, null is to be used over undefined in your scripts. undefined is given to you by the JavaScript interpreter in certain situations, and it is useful to be able to notice these situations when they appear. Listing 1 shows the difference between the two. Listing 1: Undefined and Null 1 var name; 2 // Will say"Hello undefined" 3 a l e r t( "Hello" + name); 4 5 name= prompt( "Do not answer this question" ); 6 // Will say"Hello null" 7 a l e r t( "Hello" + name); 1.2 Booleans The Boolean type has two values, true and false. -

PHP: Constructs and Variables Introduction This Document Describes: 1

PHP: Constructs and Variables Introduction This document describes: 1. the syntax and types of variables, 2. PHP control structures (i.e., conditionals and loops), 3. mixed-mode processing, 4. how to use one script from within another, 5. how to define and use functions, 6. global variables in PHP, 7. special cases for variable types, 8. variable variables, 9. global variables unique to PHP, 10. constants in PHP, 11. arrays (indexed and associative), Brief overview of variables The syntax for PHP variables is similar to C and most other programming languages. There are three primary differences: 1. Variable names must be preceded by a dollar sign ($). 2. Variables do not need to be declared before being used. 3. Variables are dynamically typed, so you do not need to specify the type (e.g., int, float, etc.). Here are the fundamental variable types, which will be covered in more detail later in this document: • Numeric 31 o integer. Integers (±2 ); values outside this range are converted to floating-point. o float. Floating-point numbers. o boolean. true or false; PHP internally resolves these to 1 (one) and 0 (zero) respectively. Also as in C, 0 (zero) is false and anything else is true. • string. String of characters. • array. An array of values, possibly other arrays. Arrays can be indexed or associative (i.e., a hash map). • object. Similar to a class in C++ or Java. (NOTE: Object-oriented PHP programming will not be covered in this course.) • resource. A handle to something that is not PHP data (e.g., image data, database query result).