Migration, Music and Social Relations on the NSW Far North Coast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Download Internet Service Channel Lineup

INTERNET CHANNEL GUIDE DJ AND INTERRUPTION-FREE CHANNELS Exclusive to SiriusXM Music for Business Customers 02 Top 40 Hits Top 40 Hits 28 Adult Alternative Adult Alternative 66 Smooth Jazz Smooth & Contemporary Jazz 06 ’60s Pop Hits ’60s Pop Hits 30 Eclectic Rock Eclectic Rock 67 Classic Jazz Classic Jazz 07 ’70s Pop Hits Classic ’70s Hits/Oldies 32 Mellow Rock Mellow Rock 68 New Age New Age 08 ’80s Pop Hits Pop Hits of the ’80s 34 ’90s Alternative Grunge and ’90s Alternative Rock 70 Love Songs Favorite Adult Love Songs 09 ’90s Pop Hits ’90s Pop Hits 36 Alt Rock Alt Rock 703 Oldies Party Party Songs from the ’50s & ’60s 10 Pop 2000 Hits Pop 2000 Hits 48 R&B Hits R&B Hits from the ’80s, ’90s & Today 704 ’70s/’80s Pop ’70s & ’80s Super Party Hits 14 Acoustic Rock Acoustic Rock 49 Classic Soul & Motown Classic Soul & Motown 705 ’80s/’90s Pop ’80s & ’90s Party Hits 15 Pop Mix Modern Pop Mix Modern 51 Modern Dance Hits Current Dance Seasonal/Holiday 16 Pop Mix Bright Pop Mix Bright 53 Smooth Electronic Smooth Electronic 709 Seasonal/Holiday Music Channel 25 Rock Hits ’70s & ’80s ’70s & ’80s Classic Rock 56 New Country Today’s New Country 763 Latin Pop Hits Contemporary Latin Pop and Ballads 26 Classic Rock Hits ’60s & ’70s Classic Rock 58 Country Hits ’80s & ’90s ’80s & ’90s Country Hits 789 A Taste of Italy Italian Blend POP HIP-HOP 750 Cinemagic Movie Soundtracks & More 751 Krishna Das Yoga Radio Chant/Sacred/Spiritual Music 03 Venus Pop Music You Can Move to 43 Backspin Classic Hip-Hop XL 782 Holiday Traditions Traditional Holiday Music -

The Sound of Ruins: Sigur Rós' Heima and the Post

CURRENT ISSUE ARCHIVE ABOUT EDITORIAL BOARD ADVISORY BOARD CALL FOR PAPERS SUBMISSION GUIDELINES CONTACT Share This Article The Sound of Ruins: Sigur Rós’ Heima and the Post-Rock Elegy for Place ABOUT INTERFERENCE View As PDF By Lawson Fletcher Interference is a biannual online journal in association w ith the Graduate School of Creative Arts and Media (Gradcam). It is an open access forum on the role of sound in Abstract cultural practices, providing a trans- disciplinary platform for the presentation of research and practice in areas such as Amongst the ways in which it maps out the geographical imagination of place, music plays a unique acoustic ecology, sensory anthropology, role in the formation and reformation of spatial memories, connecting to and reviving alternative sonic arts, musicology, technology studies times and places latent within a particular environment. Post-rock epitomises this: understood as a and philosophy. The journal seeks to balance kind of negative space, the genre acts as an elegy for and symbolic reconstruction of the spatial its content betw een scholarly w riting, erasures of late capitalism. After outlining how post-rock’s accommodation of urban atmosphere accounts of creative practice, and an active into its sonic textures enables an ‘auditory drift’ that orients listeners to the city’s fragments, the engagement w ith current research topics in article’s first case study considers how formative Canadian post-rock acts develop this concrete audio culture. [ More ] practice into the musical staging of urban ruin. Turning to Sigur Rós, the article challenges the assumption that this Icelandic quartet’s music simply evokes the untouched natural beauty of their CALL FOR PAPERS homeland, through a critical reading of the 2007 tour documentary Heima. -

The Cowl 2 NEWS October 4,1996 News Briefs Inside President’S Forum Presents First Event Congress the First Event in the Ber 10, at 7:30

Vol. LXI No. 4 Providence College - Providence, Rhode Island October 4,1996 “Belligerent, Uneducated Brutes...” He then proceeded to enter through in the car, the PPDR claims that well. he would be charged with “main by Mary M. Shaffrey ’97 door and encountered the band Bennett and the assisting officer, With everyone out of the house, taining a liquor nuisance.” With Editor-In-Chief and more students drinking out of Ptlm. Sisson, re-entered the house Jim Forker ‘97, according to the this, the report alleges, Forker at and Pete Keenan ’99 red cups. He proceeded to ask stu and were able to stop the band from report, approached the officers and tempted to flee, but was appre A&E Writer dents who lived there, and was met hended and placed in a police car. The above adjectives are how with blank stares. With this, he Both Testa and Forker were trans one bystander described the arrest asked students if they did not live ported to Central Station and held ing officers who broke up an off- there to please leave. Again, ac for the next session of 6th District campus party last Saturday cording to the PPDR, he was met Court. evening. with ignorant expressionless faces. The PPDR alleges that during Approximately 35 people were At about this time, according to the course of this investigation, a gathered to listen to Rhino as they the report, Brian Testa ‘97 ap large crowd gathered outside. celebrated Brian Testa’s 21 st birth proached Ptlm. Bennett and asked With this crowd came insults and day. -

ADAM and the ANTS Adam and the Ants Were Formed in 1977 in London, England

ADAM AND THE ANTS Adam and the Ants were formed in 1977 in London, England. They existed in two incarnations. One of which lasted from 1977 until 1982 known as The Ants. This was considered their Punk era. The second incarnation known as Adam and the Ants also featured Adam Ant on vocals, but the rest of the band changed quite frequently. This would mark their shift to new wave/post-punk. They would release ten studio albums and twenty-five singles. Their hits include Stand and Deliver, Antmusic, Antrap, Prince Charming, and Kings of the Wild Frontier. A large part of their identity was the uniform Adam Ant wore on stage that consisted of blue and gold material as well as his sophisticated and dramatic stage presence. Click the band name above. ECHO AND THE BUNNYMEN Formed in Liverpool, England in 1978 post-punk/new wave band Echo and the Bunnymen consisted of Ian McCulloch (vocals, guitar), Will Sergeant (guitar), Les Pattinson (bass), and Pete de Freitas (drums). They produced thirteen studio albums and thirty singles. Their debut album Crocodiles would make it to the top twenty list in the UK. Some of their hits include Killing Moon, Bring on the Dancing Horses, The Cutter, Rescue, Back of Love, and Lips Like Sugar. A very large part of their identity was silohuettes. Their music videos and album covers often included silohuettes of the band. They also have somewhat dark undertones to their music that are conveyed through the design. Click the band name above. THE CLASH Formed in London, England in 1976, The Clash were a punk rock group consisting of Joe Strummer (vocals, guitar), Mick Jones (vocals, guitar), Paul Simonon (bass), and Topper Headon (drums). -

Health Resource Ctr. Library Catalog

Faith Regional Health Services Health Resource Center (402) 644-7348 Items by Category - with Location 29 Jun 2009 2:31 PM Library Materials by Category Title Author Location Order Category: Adolescent Health Body Image for Boys Cambridge Educational Boundaries in dating : making dating work Cloud, Henry. / Townsend, John Sims, 1952- Caring for your teenager : the complete and Greydanus, Donald E. / Bashe, Philip. authoritative guide / American Academy of Pediatrics. Chicken soup for the teenage soul : 101 stories Canfield, Jack, 1944- / Hansen, Mark of life, love, and learning Victor. / Kirberger, Kimberly, 1953- Chicken soup for the teenage soul II : 101 more Canfield, Jack, 1944- / Hansen, Mark stories of life, love, and learning Victor. / Kirberger, Kimberly, 1953- Chicken soup for the teenage soul III : more Canfield, Jack, 1944- / Hansen, Mark stories of life, love, and learning Victor. / Kirberger, Kimberly, 1953- Chicken soup for the teenage soul IV : stories of Canfield, Jack, 1944- life, love, and learning Coping with Stress (adolescents) Packard, Gwen Dangerous dating : helping young women break Gaddis, Patricia Riddle. out of abusive relationships Girltalk : all the stuff your sister never told you Weston, Carol. Healthy teens, body and soul : a parent's Marks, Andrea, M.D. / Rothbart, Betty. complete guide to adolescent health How to say it to teens : talking about the most Heyman, Richard D. important topics of their lives The myth of maturity : what teenagers need Apter, T. E. from parents to become adults Private and personal : questions and answers Weston, Carol. for girls only Queen Bees & Wannabees : Helping your Wiseman, Rosalind daughter survive cliques, gossip, boyfriends & other realities of adolescence Raising Strong Daughters Gadeberg, Jeanette Science of the sexes : Growing up Discovery channel Science of the sexes - 2 part series : Different Discovery channel by design Sex and sensibility : the thinking parents guide M.S., Deborah M. -

Is Rock Music in Decline? a Business Perspective

Jose Dailos Cabrera Laasanen Is Rock Music in Decline? A Business Perspective Helsinki Metropolia University of Applied Sciences Bachelor of Business Administration International Business and Logistics 1405484 22nd March 2018 Abstract Author(s) Jose Dailos Cabrera Laasanen Title Is Rock Music in Decline? A Business Perspective Number of Pages 45 Date 22.03.2018 Degree Bachelor of Business Administration Degree Programme International Business and Logistics Instructor(s) Michael Keaney, Senior Lecturer Rock music has great importance in the recent history of human kind, and it is interesting to understand the reasons of its de- cline, if it actually exists. Its legacy will never disappear, and it will always be a great influence for new artists but is important to find out the reasons why it has become what it is in now, and what is the expected future for the genre. This project is going to be focused on the analysis of some im- portant business aspects related with rock music and its de- cline, if exists. The collapse of Gibson guitars will be analyzed, because if rock music is in decline, then the collapse of Gibson is a good evidence of this. Also, the performance of independ- ent and major record labels through history will be analyzed to understand better the health state of the genre. The same with music festivals that today seem to be increasing their popularity at the expense of smaller types of live-music events. Keywords Rock, music, legacy, influence, artists, reasons, expected, fu- ture, genre, analysis, business, collapse, -

Jorgensen 2019 the Semi-Autonomous Rock Music of the Stones

Sound Scripts Volume 6 | Issue 1 Article 12 2019 The eS mi-Autonomous Rock Music of The tS ones Darren Jorgensen University of Western Australia Recommended Citation Jorgensen, D. (2019). The eS mi-Autonomous Rock Music of The tS ones. Sound Scripts, 6(1). Retrieved from https://ro.ecu.edu.au/soundscripts/vol6/iss1/12 This Refereed Article is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/soundscripts/vol6/iss1/12 Jorgensen: The Semi-Autonomous Rock Music of The Stones The Semi-Autonomous Rock Music of The Stones by Darren Jorgensen1 The University of Western Australia Abstract: The Flying Nun record the Dunedin Double (1982) is credited with having identified Dunedin as a place where independent, garage style rock and roll was thriving in the early 1980s. Of the four acts on the double album, The Stones would have the shortest life as a band. Apart from their place on the Dunedin Double, The Stones would only release one 12” EP, Another Disc Another Dollar. This essay looks at the place of this EP in both Dunedin’s history of independent rock and its place in the wider history of rock too. The Stones were at first glance not a serious band, but by their own account, set out to do “everything the wrong way,” beginning with their name, that is a shortened but synonymous version of the Rolling Stones. However, the parody that they were making also achieves the very thing they set out to do badly, which is to make garage rock. Their mimicry of rock also produced great rock music, their nonchalance achieving that quality of authentic expression that defines the rock attitude itself. -

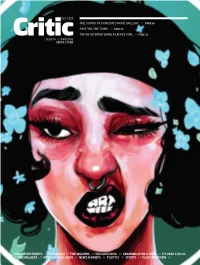

The Sound of Dunedin's None Gallery // Page 20 Painting

THE SOUND OF DUNEDIN’S NONE GALLERY // PAGE 20 PAINTING THE TOWN // PAGE 23 THE NZ INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL // PAGE 26 ISSUE 18 // 3 AUG 2015 CRITIC.CO.NZ OTAGO DIVESTMENTS // EXECRABLE // FIRE WALKERS // DESIGN SCHOOL // GRANDMA SPINS A YARN // ICT GRAD SCHOOL // FIRE WALKERS // INTERNATIONAL NEWS // NEWS IN BRIEFS // POLITICS // SPORTS // FLUKE INTERVIEW // ISSUE 18 : 3 AUGUST 2015 FEATURES 20 DUNEDIN’S NONE GALLERY A short walk up Stafford, a street lined with disused- warehouses and an old furniture distributor, one will find None Gallery. It is a residential studio and gallery complex that is a mainstay of Dunedin’s alternative sound subculture and independent arts. BY GEORGE ELLIOT 23 PAINTING THE TOWN 23 The work on our walls is sparking more creative expression and engaging the Dunedin public. “We are consciously targeting places that are out of the way for people today, like car parks and demolished buildings. These areas used to be busy. They were once the hub of the city and things change, but there is still something special there.” BY JESSICA THOMPSON 26 NZ INTERNATIONAL FILM FEST Films are about looking through another person’s eyes, entering their life and seeing how their world operates. The NZIFF offers multiple opinions, visions and lives for us to enter — ones we wouldn’t normally 20 26 see with blockbuster films. BY MANDY TE NEWS & OPINION COLUMNS CULTURE 04 OTAGO DIVESTS 38 LETTERS 30 SCREEN AND STAGE 05 EXECRABLE 42 SOMETHING CAME UP 32 ART 06 NEWS 42 DEAR ETHEL 33 GAMES 10 INTERNATIONAL NEWS 43 SCIENCE, BITCHES! -

Appendix a Manly Vale Hotel Chief Health and Building Surveyor's Recommendations Regarding Renewal of Licence, Based Upon Board

Appendix A Manly Vale Hotel Chief Health and Building Surveyor's recommendations regarding renewal of licence, based upon Board of Fire Commissioners Report. Source: Warringah Council File 1075/240-252 - G 1984. 1. Install hose reels and hydrants throughout the entire building as specified by the provisions of Parts 27.3 and 27.4 of Ordinance 70. 2. Provide emergency lighting and illuminated exit signs throughout the entire building as specified by the provisions of Clauses 24.29, 55.12 and 55.13 of Ordinance 70. 3. Remove all barrel bolts, deadlocks, chains and padlocks to all exit doors and doors leading to an exit door and replace with a latch that complies with Clause 24.20(7) of Ordinance 70. 4. Install a one hour fire rated shelter and a one hour fire rated door and jamb and self-closer to the kitchen servery, adjacent to the Peninsula bar room. 5. Install a fire blanket in the kitchen located in the first floor. 6. Install two kilogram C02 fire extinguishers in the kitchen located on the first floor. 7. Install an approved alarm device in the coolrooms located in the kitchen on the first floor and the coolroom located on the ground floor as specified by the provisions of Clause 53.2(l)(b) of Ord 70. 8. Construct a two hour fire rated wall around the dumb waiters service hoist located in the kitchen and in the cellar on the ground floor specified by Clause 16.8 of Ordinance 70. 9. Install a one hour fire rated door to both dumb waiter and service hoist, the doors to be so designed that they only open at the level at which the dumb waiter is parked. -

Grinspoon Guide to Better Living + Bonus Live EP Mp3, Flac, Wma

Grinspoon Guide To Better Living + Bonus Live EP mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Guide To Better Living + Bonus Live EP Country: Australia Released: 1998 Style: Alternative Rock, Hard Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1317 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1348 mb WMA version RAR size: 1924 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 797 Other Formats: MP1 VQF FLAC VOX MOD ASF AU Tracklist Hide Credits Guide To Better Living 1-01 Pressure Tested 1984 2:46 1-02 Boundary 2:32 1-03 DC X 3 2:55 1-04 Sickfest 3:12 1-05 Railrider 4:07 1-06 Scalped 2:36 1-07 Pedestrian 2:16 1-08 Just Ace 1:48 1-09 Post Enebriated Anxiety 2:38 1-10 Repeat 3:17 1-11 NBT 2:25 1-12 Don't Go Away 2:55 1-13 Balding Matters 2:34 Bad Funk Stripe 1-14 4:43 Keyboards – Piet Boon 1-15 Champion 2:41 1-16 Truk 4:08 Guide To Better Living Bonus Disc 2-01 Just Ace 1:48 2-02 Grudgefest Intro 0:34 2-03 More Than You Are (Live) 2:55 2-04 Freezer (Live) 2:04 2-05 Post Enebriated Anxiety (Live) 3:09 2-06 NBT (Live) 2:50 2-07 Just Ace (Live) 2:01 Companies, etc. Recorded At – Grudgefest Credits Mastered By – Don Bartley Mixed By [Assistant] – Aaron Pratley Producer – Grinspoon Producer, Mixed By – Phillip McKellar Recorded By [Assistant] – Greg Courtney Notes Includes the Just Ace single as a bonus live EP. -

Not Your Typical Evening Of

Eastern Illinois University The Keep February 2004 2-12-2004 Daily Eastern News: February 12, 2004 Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2004_feb Recommended Citation Eastern Illinois University, "Daily Eastern News: February 12, 2004" (2004). February. 9. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2004_feb/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the 2004 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in February by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REVIEW THIS Disney’s ‘Miracle’.S.A. U g delivers the goldpellin com The Hockey1980 drama“Miracle” based on 5B the , characPagteers story ◆ key team offers “Tell the truth hoc GradeFebruary: 12, 2004 THURSDAY W EEKEND THE VE RGE OF THE and don’t be afraid.” O N 2004 y 12, Februar ion B day Sect Thurs VOLUME 88, NUMBER 98 Feel the love THEDAILYEASTERNNEWS.COM The most romantic weekend of the year this weekend Get the scoop on affordable gifts he history of to get your significant other and , get cheap gift ◆Learn abouts Day t Valentine’ See page 3B HAAS BY STEPHEN ideas and pick out movies toTION the history of Valentine’s Day. PHOTO ILLUSTRA AR celebrate or boycott the occasionCALEND T ow benefit eepsh a P s Day-themed CONCER eekend’ z Fest, Jaz alentine’ EIU slew of Vinate the w and a activities. shows dom ◆ T REVIEWhe can shows the bestard. of Page 8B CONCER illiamsmusic III with y rock awfully h Hank countW r ivery and also del his lineage TURE lotte ◆ F EA vision Page 5B tele eams” ke her Dr VERGE ma Page 1B Charleston nativerican Cha r Martin to “Ame debut on this weekend.