Oral History Interview with William H. Bailey, 2012 October 10-December 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Divinity School 2013–2014

BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY BULLETIN OF YALE BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Periodicals postage paid New Haven ct 06520-8227 New Haven, Connecticut Divinity School 2013–2014 Divinity School Divinity 2013–2014 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 109 Number 3 June 20, 2013 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 109 Number 3 June 20, 2013 (USPS 078-500) The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, is published seventeen times a year (one time in May and October; three times in June and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and a∞rmatively and September; four times in July; five times in August) by Yale University, 2 Whitney seeks to attract to its faculty, sta≠, and student body qualified persons of diverse back- Avenue, New Haven CT 0651o. Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut. grounds. In accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment against Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, any individual on account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, or PO Box 208227, New Haven CT 06520-8227 national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity or expression. Managing Editor: Kimberly M. Go≠-Crews University policy is committed to a∞rmative action under law in employment of Editor: Lesley K. Baier women, minority group members, individuals with disabilities, and covered veterans. PO Box 208230, New Haven CT 06520-8230 Inquiries concerning these policies may be referred to the Director of the O∞ce for Equal Opportunity Programs, 221 Whitney Avenue, 203.432.0849. -

Music Playlist Auggie: 1

Music Playlist Auggie: 1. Ugly- Sugababes This links to Auggie because throughout the book Auggie gets more comfortable with his face being different and this is linked to the lyrics “ i got real comfortable with my own style”. the lyrics “But there will always be the one who will say something bad to make them feel great” this links to Julian asking if Auggie was in a fire and saying he looks like Darth Sideous. 2. This is me- Keala Settle This song links to Auggie because he works his way to accepting himself for who he is. The lyrics “I won’t let them break me down” Is linked to Auggie not letting people hurt him and he ignores the mean comments people make. The lyrics “I’m not scared to be seen” is linked to Auggie not getting upset or hide away when people stare at him. Via: 1. Ok not to be ok- Demi Lovato and Marshmello This song links to Via because she does not have to act like she is ok when something is wrong just because her parents don’t pay as much attention to her as Auggie. The lyrics “Or give up when you’re closest” is linked to Via because in the book it says if she struggles on something she works it out on her own, so Via doesn’t give up until she has figured it out. 2. History- One Direction This links to Via because her and Miranda were best friends and had a lot of history. The lyrics “Thought we were going strong I thought we were holding on” links to Via because at the start of high school she found out Miranda was ditching her in the summer holidays and their friendship was falling apart. -

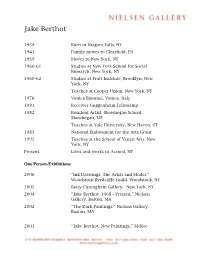

Jake Berthot

Jake Berthot 1939 Born in Niagara Falls, NY 1941 Family moves to Clearfield, PA 1959 Moves to New York, NY 1960-61 Studies at New York School for Social Research, New York, NY 1960-62 Studies at Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, New York, NY Teaches at Cooper Union, New York, NY 1976 Venice Biennial, Venice, Italy 1981 Receives Guggenheim Fellowship 1982 Resident Artist, Skowhegan School, Skowhegan, ME Teaches at Yale University, New Haven, CT 1983 National Endowment for the Arts Grant 1992 Teaches at the School of Visual Arts, New York, NY Present Lives and works in Accord, NY One Person-Exhibitions 2006 “Ink Drawings: The Artist and Model,” Woodstock Byrdcliffe Guild, Woodstock, NY 2005 Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York, NY 2004 "Jake Berthot: 1968 - Present," Nielsen Gallery, Boston, MA 2002 “The Dark Paintings,” Nielsen Gallery, Boston, MA 2001 “Jake Berthot, New Paintings,” McKee Gallery, New York, NY 2002 "Landscape Paintings & Drawings," Nielsen Gallery, Boston, MA 1999 "Trees: Drawings and Texts," Humanities Gallery, The Cooper Union, New York, NY 1998 “Paintings and Drawings,” Nielsen Gallery, Boston, MA 1997 “New Paintings and Drawings,” McKee Gallery, New York, NY 1996 “Drawings,” McKee Gallery, New York, NY “Enamel Drawings," Nielsen Gallery, Boston, MA 1995 “Jake Berthot: The Red Paintings,” Nielsen Gallery, Boston, MA “Jake Berthot,” Jaffe-Friede and Strauss Galleries, Hopkins Center, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH 1994 “Jake Berthot: The Kristin Paintings and Works on Paper,” David McKee Gallery, New York, NY “Jake Berthot : Paintings and Works on Paper,” David McKee Gallery, New York, NY 1992 “Jake Berthot - Paintings,” Toni Oliver Gallery, Sydney, Australia. -

Moments of Observation

John Walker Moments of Observation Sheldon Museum of Art January 18–July 14, 2019 Introduction and Beer With a Painter: John Walker, Revisited by Jennifer Samet ohn Walker’s recent paintings are about a compression of energy: forms and patterns J locked into one another. There is an urgency to his most recent paintings, a directness that is about that relationship between a person and a place, and the impulse to record that relationship through mark making. It is symbolized by how the forms lock into one another: the penetration of earth and shallow water. I think about the painting by Cezanne, The Bay of Marseilles, Seen from L’Estaque, which is also about water and shore locking into one another like mirroring, perfect jigsaw puzzle pieces. For more than fifteen years, Walker has turned his attention and gaze to Seal Point, Maine, where he lives and works. But in the newest paintings, Walker pares down his formal vocabulary to elements like patterns of zigzag lines, painterly, irregular grids, oval-shaped forms and dots. They are abstractions, but they are also landscape paintings that turn the genre on its head. They are oriented vertically, rather than the horizontal format we traditionally code as landscape. The horizon line is pushed to the uppermost portion of the canvas so that only a thin band of form suggests sky, clouds, sun or moon. Instead, Walker focuses on the patterns that form when earth and water meet. And in this area of Maine, the inlets and bays are as much about mud as they are about water. -

Meals+With+Faculty+Program+Semester+Report+

Introduction Every day, Yale College students interact with their instructors, which include professors, lecturers, and teaching fellows. However, these interactions are typically limited to the classroom and office hours, and relationships tend not to continue past the end of the semester. By creating another way in which students can interact with faculty, students will have the ability to develop stronger relationships, which are valuable for both students and faculty. A Meals with Faculty program would allow students to interact more easily with professors, lecturers, and teaching fellows outside of typical learning spaces. This project aims to institute a robust Meals with Faculty program within Yale College. Background Currently, Yale College does not offer a college-wide Meals with Faculty program for students. Although professors in some classes invite students to meals, whether in the dining hall or off-campus, these are only a handful. There are also several residential colleges that have similar Meals with Faculty programs, such as Davenport College, Branford College, and Grace Hopper College. These college-specific programs are typically run by the residential college councils. In addition to this, students already have the opportunity to schedule meals with tenured professors, who are able to have lunches in the dining halls free of charge. However, many students are unaware of this opportunity or feel uncomfortable asking professors to a meal. A Meals with Faculty program would break down this “barrier” to interacting more with faculty. Peer Institutions Most of Yale’s peer institutions have Meals with Faculty programs in place. Each peer institution has designed a unique program to encourage relationships between students and faculty. -

Yale.Edu/Visitor Yale Guided Campus Tours Are Conducted Mon–Fri at 10:30 Am and Campus Map 2 Pm, and Sat–Sun at 1:30 Pm

sites of interest Mead Visitor Center 149 Elm St 203.432.2300 www.yale.edu/visitor Yale Guided campus tours are conducted Mon–Fri at 10:30 am and 2 pm, and Sat–Sun at 1:30 pm. No reservations are necessary, campus map and tours are open to the public free of charge. Please call for holiday schedule. Large groups may arrange tours suited to their interests and schedules; call for information and fees. selected athletic facilities Directions: From I-95 North or South, connect to I-91 North in New Haven. Take Exit 3 (Trumbull Street) and continue to third traªc light. Turn left onto Temple Street. At first traªc light, turn Yale Bowl right onto Grove Street. At first traªc light, turn left onto Col- 81 Central Ave lege Street. Continue two blocks on College Street to traªc light From downtown New Haven, go west on Chapel Street. Turn at Elm Street and turn left. The Visitor Center is on the left in the left on Derby Avenue (Rte. 34) and follow signs to Yale Bowl. middle of the first block, across from the New Haven Green. Completed in 1914 and regarded by many as the finest stadium in America for viewing football, the Bowl has 64,269 seats, each Yale University Art Gallery with an unobstructed view of the field. 1111 Chapel St 203.432.0600 Payne Whitney Gymnasium www.yale.edu/artgallery 70 Tower Pkwy The Art Gallery holds more than 185,000 works from ancient 203.432.1444 Egypt to the present day. Completed in 1932, Payne Whitney is one of the most elaborate Open Tue–Sat 10 am–5 pm; Thurs until 8 pm (Sept–June); indoor athletic facilities in the world. -

Berthot Press Release 2016

Jake Berthot: In Color March 12 – April 23, 2016 Opening Saturday March 12th, 4 – 7 PM Celebrating the career of Jake Berthot, Betty Cuningham Gallery is pleased to open Jake Berthot: In Color on Saturday, March 12th, with a reception from 4 – 7 PM. The exhibition will include approximately 20 works dating from 1969 to 2014. As this is the first exhibition of Berthot’s work since his death in December of 2014, the Gallery chose to feature Nympha Red, a major work only once exhibited in 1988 at the Rose Art Museum (Brandeis University). Painted in 1969, Nympha Red measures 60 ½ x 210 inches and is the ‘sister painting’ to another major horizontal painting, Walken's Ridge, 1975-6, in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art. From these two paintings – painted early in his career – the titles alone indicate Berthot’s instinctive interest in both color and landscape. Berthot began exhibiting in the mid-1960s, at a time when Abstract Expressionism, Pop and Minimalism were part of the aesthetic environment. Berthot’s early work was geometric and the color was subdued. Over the following years, his color intensified and the underlying grid opened to include an oval (some thought a portrait or a head). In 1992, Berthot moved to upstate New York where he wrote a quote from Ralph Waldo Emerson on the wall of his new studio: We may climb into the thin and cold realm of pure geometry and lifeless science, or sink into that of sensation. Between these extremes is the equator of life, of thought, or spirit, or poetry – a narrow belt. -

Divinity School 2011–2012

BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Periodicals postage paid New Haven ct 06520-8227 New Haven, Connecticut Divinity School 2011–2012 Divinity School Divinity 2011–2012 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 107 Number 3 June 20, 2011 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 107 Number 3 June 20, 2011 (USPS 078-500) The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, is published seventeen times a year (one time in May and October; three times in June and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and a∞rmatively and September; four times in July; five times in August) by Yale University, 2 Whitney seeks to attract to its faculty, sta≠, and student body qualified persons of diverse back- Avenue, New Haven CT 0651o. Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut. grounds. In accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment against Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, any individual on account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, or PO Box 208227, New Haven CT 06520-8227 national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity or expression. Managing Editor: Linda Koch Lorimer University policy is committed to a∞rmative action under law in employment of Editor: Lesley K. Baier women, minority group members, individuals with disabilities, and covered veterans. PO Box 208230, New Haven CT 06520-8230 Inquiries concerning these policies may be referred to the O∞ce for Equal Opportu- nity Programs, 221 Whitney Avenue, 203.432.0849 (voice), 203.432.9388 (TTY). -

TRADITIONS & D E P a R T U R

P ART II REALISM NOW : TRADITIONS & D e p a r t u r e s M ENTORS AND P ROTÉGÉS M ENTORS AND P ROTÉGÉS W ILL B ARNE T • Vincent Desiderio, George Wingate B ESSIE B ORI S • Mary Sipp-Green H ARVEY B REVERMA N • Thomas Insalaco C HARLES C ECI L • Matthew Collin s C HUCK C LOS E • Nancy Lawto n J ACOB C OLLIN S • John Morr a K EN D AVIE S • Michael Theis e W ILLIAM R. D AVIS , D ONALD D EMERS , J OSEPH M C G UR L PHILIP H ALE , C HARLES H AWTHORN E • Polly Thayer Star r M ORTON K AIS H • Luise Kais h B EN K AMIHIR A • Edgar Jerin s EVERETT R AYMOND K INSTLE R • Michael Shane Nea l M ICHAEL L EWI S • Charles Yode r J AMES L INEHA N • June Gre y M ARTIN LUBNE R • Stanley Goldstei n J ANET M C K ENZI E • Byron Geige l J OHN M OOR E • Iona Frombolut i C AROL M OTHNER , M ICHAEL B ERGT , D ANIEL M ORPER E LLIOT O FFNE R • Mark Zunin o R ANDALL S EXTO N • Adam Forfan g M ILLARD S HEET S • Timothy J. Clar k D ON S TONE , N.A . • Thea N. Nelso n N EIL W ELLIVE R • Melville McLean REALISM NOW : TRADITIONS & De p a rtu r es M ENTORS AND P ROTÉGÉS Part II May 17 – July 17, 2004 vose NEW AMERICAN REALISM contemporary Part II R EALISM N OW : T RADITIONS AND D EPARTURES M ENTORS AND P ROTÉGÉS May 17 to July 17, 2004 Compiled by Nancy Allyn Jarzombek with an essay by John D. -

I'll Be There for You (V1) Artist:The Rembrandts

I'll Be There For You (v1) Artist:The Rembrandts. Writer:Phil Sōlem, Danny Wilde, David Crane, Marta Kauffman, Michael Skloff, Allee Willis A -2-2-2-0------------0-----2-2-2-0--------------0---- E -3---------3-1-1-3-----3--3----------3-1-1-3-----3- C -2---------------------------2--------------------------- G -0---------------------------0--------------------------- Strumming Pattern: Island Strum Intro: [G] [F] [G] [F] [G] So no one told you life was gonna be this [F] way [G] Your job's a joke, you're broke, your love life's [Gmaj7] D.O.A. [F] It's like you're [C] always stuck in [G] second gear And it [F] hasn't been your [C] day, your week Your [D] month or even your [D7] year, but Gmaj7 [G] I'll be [C] there for [D] you, when the rain starts to [G] pour I'll be [C] there for [D] you, like I've been there be-[G]fore I'll be [C] there for [D] you, 'cause you're there for me [F] too [F] [G] You're in bed at ten and work began at [F] eight [G] You've burned your breakfast so far things are going [Gmaj7] great [F] Your mother [C] warned you there'd be [G] days like these But she [F] didn’t tell you [C] when the world has [D] brought You down to your [D7] knees that [G] I'll be [C] there for [D] you, when the rain starts to [G] pour I'll be [C] there for [D] you, like I've been there be-[G]fore I'll be [C] there for [D] you, 'cause you're there for me [F] too [F] [G] [G] [C] No one could ever know me, no one could ever see me [Em] Sometimes the only one who knows what it's like to be me [Am] Someone to face the day with, [Am7] make it through -

New Work on Paper I John Elderfield

New work on paper I John Elderfield Author Elderfield, John Date 1981 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2019 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art NEW WORK ON PAPER JAKE BERTHOT DAN CHRISTENSEN ALAN COTE TOM HOLLAND YVONNE JACQUETTE KEN KIFF JOAN SNYDER WILLIAM TUCKER JOHN ELDERFIELD THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART NEW YORK NEW WORK ON PAPER 1 Thisis the first in a seriesof exhibitionsorganized by The Museumof ModernArt, New York, each of whichis intendedto showa relativelysmall number of artists througha broadand representativeselection of their recentwork on paper.Emphasis is placedon newwork, with occasionalglances backward to earlierproduction where the characterof the art especially reguiresit, and on artists or kindsof art not seenin depth at the Museumbefore. Beyond this, no restrictionsare imposedon the series,which may include exhibitions devoted to heterogeneous and to highlycompatible groups of artists, and selectionsof workranging from traditional drawing to workson paper in mediaof all kinds.Without exception, however, the artists includedin each exhibitionare presentednot as a definitive selectionof outstandingcontemporary talents but as a choice, limitedby necessitiesof space, of only a fewof those whose achievementmight warrant their inclusion— and a choice, moreover,that is entirelythe responsibilityof the directorof the exhibition,who wished to share someof the interestand excite mentexperienced in lookingat newwork on paper. NEW WORK ON PAPER 1 JOHN ELDERFIELD THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK Copyright© 1981by The Museumof ModernArt TRUSTEES OF THE MUSEUM Jr.,Mrs. -

American Art Today: Contemporary Landscape the Art Museum at Florida International University Frost Art Museum the Patricia and Phillip Frost Art Museum

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons Frost Art Museum Catalogs Frost Art Museum 2-18-1989 American Art Today: Contemporary Landscape The Art Museum at Florida International University Frost Art Museum The Patricia and Phillip Frost Art Museum Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/frostcatalogs Recommended Citation Frost Art Museum, The Art Museum at Florida International University, "American Art Today: Contemporary Landscape" (1989). Frost Art Museum Catalogs. 11. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/frostcatalogs/11 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the Frost Art Museum at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Frost Art Museum Catalogs by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RIGHT: COVER: Howard Kanovitz Louisa Matthiasdottir Full Moon Doors, 1984 Sheep with Landscape, 1986 Acrylic on canvas/wood construction Oil on canvas 47 x 60" 108 x ;4 x 15" Courtesy of Robert Schoelkopf Gallery, NY Courtesy of Marlborough Gallery, NY American Art Today: Contemporary Landscape January 13 - February 18, 1989 Essay by Jed Perl Organized by Dahlia Morgan for The Art Museum at Florida International University University Park, Miami, Florida 33199 (305) 554-2890 Exhibiting Artists Carol Anthony Howard Kanovitz Robert Berlind Leonard Koscianski John Bowman Louisa Matthiasdottir Roger Brown Charles Moser Gretna Campbell Grover Mouton James Cook Archie Rand James M. Couper Paul Resika Richard Crozier Susan Shatter