Passover for the Rest of Us

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Torah Family E-Magazine Issue #4

Torah Family E-Magazine Issue #4 This magazine is a special place for Torah keeping families to learn and share and grow together. Whether you are 2 or 69, you will find something here for you. Enjoy and Shalom! Torah Family e-magazine is a publication just for families that are trying to keep Torah. Everyone gets a chance to share, from children to grandparents. This magazine is owned and operated by Heidi Cooper, and all submissions are checked and placed by her. Please enjoy reading the material, and be sure to share what you have learned with everyone else. Ads or classifieds are available for $5 per issue, and will be placed within the magazine as well as on the www.torahfamilyliving.com website. Categories accepted include: Torah, crafts, homesteading, herbs, modesty, home schooling, general Scriptures. This magazine is available to all for free and all submissions are given freely. Each issue will be available in PDF download at the www.torahfamilyliving.com website. Thank you very much for taking part in this project. Affiliate links have been used in this issue. If you click through these links and make a purchase, a small percentage of the sale goes towards keeping this magazine free for all to enjoy. Thank you for your support. Index 2- Intro and Index 3- Children's Gallery 5- A Barn Surprise: Copywork 9- Torah Family Interview: Pamela Matos 12- 36 Cool things to do for Pesach 15- Hebrew Roots Devotional: Dining with Yahshua HaMashiach 17- Time for a Shofar, Shofar for a Time 20- Modesty from a Father's Perspective 23- Hebrew Vocabulary Cards for Pesach 27- Time with Yahshua announcement Coloring page drawn by Holly, age 8. -

Passover Menu

CLASSIC TO GO PASSOVER MENU www.classiccatering.com 410.356.1666 PASSOVER PASSOVER TRADITIONAL DINNER CONTEMPORARY DINNER $199, serves 10 $285, serves 10 no substitutions additional entrées available no substitutions additional entrées available SEDER PLATE INGREDIENTS SEDER PLATE INGREDIENTS roasted lamb bone, roasted hard boiled egg, parsley, roasted lamb bone, roasted hard boiled egg, parsley, horseradish root horseradish root & traditional charoset & traditional charoset TRADITIONAL CHAROSET TRADITIONAL CHAROSET apples, walnuts, cinnamon & sweet Passover wine apples, walnuts, cinnamon & sweet Passover wine TURKISH CHAROSET CHICKEN BROTH & MATZO BALLS dates, prunes, apricots, almonds, sweet Passover wine GRILLED BONELESS BREAST OF CAPON SHORT RIBS PROVENCAL tomato chutney MEDITERRANEAN OLIVE CAPON green olives, lime juice, oregano, garlic RED BLISS POTATOES, CARROTS & ONIONS ROASTED ASPARAGUS FARRO & ROASTED MUSHROOM RISOTTO lemon, pepper & thyme HARICOT VERT FLOURLESS CHOCOLATE CAKE red pepper glaze PINE NUT ROLL Add a second entrée of oven roasted brisket Add Roasted Carrot, Apple & Celery Root Soup with gravy for $58.50, serves 10 for $36, serves 10 PASSOVER À LA CARTE STARTERS ENTRÉES SEDER PLATE INGREDIENTS $14 TENDERLOIN OF BEEF $165 roasted lamb bone, roasted hard boiled egg, parsley, horseradish root & traditional charoset seared, oven ready or roasted carved & garnished TRADITIONAL CHAROSET $16 TRADITIONAL BEEF BRISKET $21 apples, walnuts, cinnamon & sweet Passover wine 1st cut - beef gravy price per quart price per pound -

The Holidays 2020 Holidays Feel a Bit Different This Year, So We’Ve Created a Flavorful Menu to Celebrate the Season

BY CONSTELLATION THE HOLIDAYS 2020 HOLIDAYS FEEL A BIT DIFFERENT THIS YEAR, SO WE’VE CREATED A FLAVORFUL MENU TO CELEBRATE THE SEASON. GATHER AROUND THE TABLE FOR AN INTIMATE FAMILY FEAST OR RING IN A TASTY NEW YEAR WITH FRIENDS, NEAR & FAR. BY CONSTELLATION HOLIDAY PARTY IN A BOX HORS D’OEUVRES $475 per box | feeds 8-10 guests room temperature bites available throughout the month, 20 pieces per platter including New Year's Eve! add on to party in a box or suppers SMOKED SALMON NAPOLEON BAR SNACK TRIO horseradish lemon crème fraîche wasabi rice & pea crunch $60 PER PLATTER spiced mixed nuts candied peanuts & popcorn KOREAN SPICED BAR SNACKS GF SHORT RIBS lime, radish, jicama cup $65 PER PLATTER ARTISAN CHEESES SOUTHWESTERN aged cheddar, manchego, brie, SPICED CHICKEN fried almonds, grapes, dried apricots, tortilla wrap, lime avocado sauce crostini $55 PER PLATTER NAKED BURRATA PERSIAN GF V help yourself toppings | caponata, CUCUMBER CUPS crisp prosciutto, fig almond, pesto fava bean hummus, olive tapenade, za’atar MEZZE SAMPLER $50 PER PLATTER SELECT hummus, baba ghanoush, olives, TWO marinated feta, stuffed grape leaves, TRUFFLE MUSHROOM GF V soft pita SKEWERS GF V artichoke & sundried tomato tapenade SHAREABLES GREENMARKET CRUDITÉ $55 PER PLATTER raw & steamed seasonal veggies, carrot hummus TRIO OF DIPS & BREADS DIPS | tomato bruschetta, olive hummus, spinach artichoke BREADS| sourdough baguette, rosemary crostini, za'atar lavash COLORFUL FRENCH MACARONS ASSORTED HOUSE MADE GF CHOCOLATE TRUFFLES SWEET ENDING GF = GLUTEN FREE V = VEGAN -

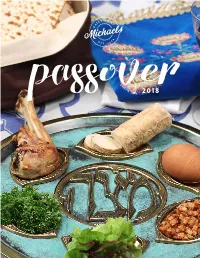

2018-Passover-Menu.Pdf

2018 * New Item V Vegetarian N Contains Nuts GF Does Not Contain Gluten Ingredients COMPLETE DINNER PACKAGE Package orders are available for 10 or more in DINNER MENU multiples of 5. All “choice” items may be divided in FIRST & SECOND COURSE multiples of 10. No substitutions or deletions. Food Homemade Gefilte Fish arrives in disposable containers except where noted. With white or beet horseradish. Matzo Ball Soup SEDER PLATE INGREDIENTS With toasted matzo farfel. 1 pan per 10 guests. CHOOSE 1 ENTRÉE ZEROA (ROASTED LAMB SHANK BONE) Mom’s Sliced Beef Brisket With mushrooms, onion and natural gravy. MAROR (FRESH HORSERADISH) or HAROSET V | N 3 oz per person. Stuffed Free Range Chicken Breast KARPAS (PARSLEY) Oven roasted skin-on imperial chicken breast stuffed with matzo-vegetable farfel, topped with apricot glaze. ROASTED EGGS V | GF 1 per 10 guests. or HARD BOILED EGGS V | GF 1 per person peeled. *House-Roasted Chicken GF Bone-in chicken lightly seasoned with garlic and paprika. PREPARED WHITE HORSERADISH or Horseradish Encrusted Salmon Filet Accompanied by horseradish cream sauce. CHOOSE 2 SIDES Sweet Potato & Apple Tzimmes V | GF Spinach, Mushroom & Onion Kugel V Apple Matzo Kugel V Kishke Must be roasted before serving. Oven Roasted Potatoes V | GF Maple Dijon Glazed Tri-Colored Carrots V | GF DON’T FORGET TO ORDER DESSERT! See our full dessert menu on pages 8-9 Complete Dinner Package 31.00/pp CATERINGBYMICHAELS.COM | 847.966.6555 02/05/18 2 * New Item V Vegetarian N Contains Nuts GF Does Not Contain Gluten Ingredients STARTERS HORS D’OEUVRE TRADITIONAL SEDER PLATE INGREDIENTS 34.25 MATZO BALLS 10 per pan. -

Passover Menu 2020

CLASSIC TO GO PASSOVER MENU 2020 www.classiccatering.com 410.356.1666 PASSOVER PASSOVER TRADITIONAL DINNER CONTEMPORARY DINNER $199, serves 10 $285, serves 10 no substitutions additional entrées available no substitutions additional entrées available SEDER PLATE INGREDIENTS SEDER PLATE INGREDIENTS roasted lamb bone, roasted hard boiled egg, parsley, roasted lamb bone, roasted hard boiled egg, parsley, horseradish root horseradish root & traditional charoset & traditional charoset TRADITIONAL CHAROSET TRADITIONAL CHAROSET apples, walnuts, cinnamon & sweet Passover wine apples, walnuts, cinnamon & sweet Passover wine TURKISH CHAROSET CHICKEN BROTH & MATZO BALLS dates, prunes, apricots, almonds, sweet Passover wine GRILLED BONELESS BREAST OF CAPON SPICED SHORT RIBS tomato chutney ROASTED ORANGE-HERB CAPON BREAST RED BLISS POTATOES, CARROTS & ONIONS FARRO & ROASTED MUSHROOM RISOTTO ROASTED ASPARAGUS lemon, pepper & thyme HARICOT VERT red pepper glaze FLOURLESS CHOCOLATE CAKE PINE NUT ROLL Add a second entrée of oven roasted brisket Add Roasted Carrot, Apple & Celery Root Soup with gravy for $58.50, serves 10 for $36, serves 10 PASSOVER À LA CARTE STARTERS ENTRÉES SEDER PLATE INGREDIENTS $14 TENDERLOIN OF BEEF $165 roasted lamb bone, roasted hard boiled egg, parsley, horseradish root & traditional charoset seared, oven ready or roasted carved & garnished TRADITIONAL CHAROSET $16 TRADITIONAL BEEF BRISKET $22.50 apples, walnuts, cinnamon & sweet Passover wine 1st cut - beef gravy price per quart price per pound TURKISH CHAROSET $25 GLAZED CORNED -

2021 Passover Guide Shamayim: Jewish Animal Advocacy | Shamayim.Us What Is Passover? (Continued)

Passover Guide The holiday and its connection to animal welfare, recipes, and more. What is Passover? Passover or Pesach is a Jewish festival that occurs in the springtime (in the Northern Hemisphere) each year. It commemorates the liberation of the enslaved Israelites from bondage in Egypt and the miraculous way(s) in which the string of horrific plagues spared one group and badly affected another. The manner in which the Israelites were passed over time and time again is the source of the holiday’s namesake and to many of our Sages, it’s also a definitive reaffirmation of HaShem’s commitment to the Abrahamic covenant. More still, the story of the Passover shows us how much change one, solitary person can put into motion when they find the courage to stand up to injustice. “‘Speak truth to power!’ ‘Power is corrupt!’ These popular mantras have fueled rhetorical wars among the classes for generations and are still voiced by many activists today. The disdain for power long predates the Marxists and the counter- culture activists; it enters the discourse of the early Rabbis in the Mishnah: ‘Love work, hate holding power, and do not seek to become intimate with the authorities,’ (Pirke Avot 1:10). The Rabbis urge us to resist attaining power or being influenced by the powerful not only for ethical concerns, but also for concern of one’s own success, with the words: ‘Woe to authority, for it buries those who hold it; there is not a single prophet who did not outlive four kings.’” - (Rabbi Shmuly Yanklowitz) The above quote, the words of Shamayim’s founder, was published in July, but of which year? 2020? 2019? 2010. -

Spice up Passover with These Matzo Recipes

Matzo Recipes Ideas: 8 Ways To Spice Up Passover! Entertainment Fashion+Beauty Entertainment VIDEO: Eiza Gonzalez Denise Bidot Launches En Is Kate Del Castillo Refuses To Talk About 'No Wrong Way' 5 Be Meeting 'El Chapo' In Giovani Dos Santos Movement With 'La P NY Jail? Romance Unretouched Photos Lifestyle ADVERTISEMENT Matzo Recipes Ideas: 8 Ways To Spice Up Passover! Like Twitter Comment Email By Maria G. Valdez | Apr 22 2016, 02:56AM EDT Most Read 1. Entertainment Is Kate Del Castillo Meeting 'El Chapo' In NY Jail? 2. Lifestyle 5 Ways To Rum Right All Year Long 3. Entertainment 'El Capo' Telenovela Cast: Mauricio Islas Stars In Telemundo Narco Series 4. Entertainment VIDEO: Eiza Gonzalez Refuses To Talk About Giovani Dos Santos Romance Not your average matzo ball soup! Check these delicious recipes out, perfect for Passover! Shutterstock/LeonP 5. Entertainment Netflix April 2017 Full List New Releases: See What Movies, TV Series Are Coming Bring on the Matzo! It’s Passover from Friday, April 22, until Saturday, April 30, so that means leavened bread is out of the question for our Jewish friends. That’s when Matzo, which is unleavened ADVERTISEMENT bread, comes in. Passover, or Pesach, is the commemoration of the Jewish Exodus from Egypt after generations of slavery. In the narrative of the Exodus, the Bible tells that God helped the Children of Israel escape from their slavery in Egypt by inflicting ten plagues upon the ancient Egyptians before the Pharaoh would release his Israelite slaves. After the last plague ended the lives of the Egyptian male firstborn, the Pharaoh chased his former slaves out of the land. -

Ala Carte Hot Selections Are Not Available on Saturday Due to Shabbat****

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday March 29, 2021 March 30, 2021 March 31, 2021 April 1, 2021 April 2, 2021 April 3, 2021 April 4, 2021 Breakfast/Dairy Breakfast/Dairy Breakfast/Dairy Breakfast/Dairy Breakfast/Dairy Breakfast/Dairy Breakfast/Dairy Choice of Juice Choice of Juice Choice of Juice Choice of Juice Choice of Juice Choice of Juice Choice of Juice Cream of Mazto Passover Cold Cereal Cream of Matzo Cream of Matzo Passover Cold Cereal Passover Cold Cereal Cream of Matzo Apple Matzoh Kugel Southwest Frittata Matzo Waffle Matzo Brei Cheese Blintz Yogurt & Fruit Parfait Matza Brei Banana Home Fries Hard Boiled Egg Fresh Fruit Stewed Fruit Passover Cake Potato Latke Stewed Fruit Fresh Berries Apricots Alternate Alternate Alternate Alternate Alternate Alternate Alternate Scrambled Eggs Cottage Cheese and Fruit Matza Brei Scrambled Eggs Loaded Omelet Hard Boiled Egg Cheese Omelet Available Breakfast Alternates During Passover Passover Cold Cereal, Fruit and Yogurt Parfait,, Hard Boiled Eggs, Cottage Cheese, Cheese Omelet Juices ( Orange, Apple, Cranberry, Tomato), Coffee and Tea, Low Fat, 2%, Lactaid and Chocolate Milk Lunch/Dairy Lunch/Dairy Lunch/Dairy Lunch/Dairy Lunch/Dairy Lunch/Dairy Lunch/Dairy Beet & Onion Salad Potato Chowder Roasted Vegetable Soup Tossed Salad Caesar Salad Spinach Salad Creamy Coleslaw Vegetable Stuffed Eggplant Cheese Blintz w/ Fruit Compote Vegetable Quinoa Stir Fry Baked Lemon Dill Fish Matzo Vegetable Pizza Vegetable Cholant Fish and Chips Roasted Red Potaotes Potato Gratin Fresh -

Congregation Beth Yeshurun Sisterhood 2020/5780 Passover Cookbook TABLE of CONTENTS

Congregation Beth Yeshurun Sisterhood 2020/5780 Passover Cookbook TABLE OF CONTENTS Appetizers ● Chopped Liver ● Gefilte Fish Ball ● Gefilte Fish Dip ● Tri-Color Gefilte Fish Entrees ● Atlanta Brisket (aka Coca Cola Brisket) ● Butternut Squash Matzo Lasagna ● Cornish Hens with Apricots and Prunes ● Honey Horseradish Roasted Chicken ● Passover Cheese Blintzes ● Passover Sweet & Sour Meatballs (May also be an Appetizer) ● Spinach Frittata ● Tzimmes Chicken with Apricots, carrots, and Prunes Sides/Vegetables ● Doughless Potato Knishes ● Gluten Free Passover Spinach Noodle Kugel ● Passover Bagels ● Passover Matzo Fruited Farfel Casserole ● Passover Matzo Stuffing ● Passover Ratatouille ● Passover Spinach Balls ● Potato Kugelettes ● Simple Glazed Carrots ● Spinach & Artichoke Matzo Kugel ● Spinach Potato Nest Bites Desserts ● Double Chocolate Pavlova with Marscapone Cream & Raspberries ● Flourless Walnut-Date Cake ● Gluten-Free Passover Chocolate Swirl Macaroon Cheesecake ● Matzoh Toffee Bar Crunch ● Passover Almond Cookies ● Passover Apple Cake 1 ● Passover Apple Cake 2 ● Passover Apple Cake 3 ● Passover Apricot Squares ● Passover Chocolate Dipped Almond Fingers ● Passover Farfel Nut Thin Cookies ● Passover Hot Fruit Compote ● Passover Macaroon Cheesecake ● Passover Mandel Bread ● Passover Meringues ● Passover Pistachio Brittle Chopped Liver Serves 8 Ingredients: 1 lb. of chicken livers, washed and membranes trimmed 2 large yellow onions, thinly sliced 6 Tablespoons of Schmaltz (chicken fat) 3 hard boiled eggs Salt and pepper, to taste Directions: In a heavy large skillet, fry your onions in chicken fat on medium heat for about 7 minutes until golden. Salt the chicken livers add to the same pan with the onions. Simmer for about 15 minutes until all the pink is out of the liver. The onions will continue to cook down. -

Recipe Nutrition Counseling Matzo Lasagna for Passover the JCC Is Proud to Offer a Passover Commemorates the Liberation of the Jewish Slaves from Egypt

Nutrition / Matzo Lasagna for Passover Featured RECIPE Nutrition Counseling Matzo Lasagna for Passover The JCC is proud to offer a Passover commemorates the liberation of the Jewish slaves from Egypt. The Jews had to leave in such a hurry that they could not wait for their breads to rise. Eating unleavened wide array of services that bread (matzo) during the days of Passover connects Jews of today to this event in the aid our Members in achieving past. Leavened bread and bread products, known as chametz, are prohibited during their health and fitness goals. Passover. These items include certain grain-based foods like breads, pasta, pastries, breadcrumbs, crackers, etc. This Passover-friendly recipe for Matzo Lasagna replaces Nutrition Counseling gives you pasta noodles with matzo. The trick when using matzo as noodles, is to soften them the tools you need to lead a with water so they are not dry and crumbly. This lasagna is also a great way to get extra healthy and balanced life and vegetables into your meal. The recipe calls for eggplant, but spinach can be substituted. can be tailored to your specific Ingredients needs. • 1 tbsp. olive oil • 1 large eggplant, peeled and cut • 3 cups sliced mushrooms into 1/2-inch slices. (If you choose to • 3 garlic cloves, crushed substitute spinach in lieu of eggplant, use 4 cups finely chopped) • 1/4 cup fresh parsley, chopped • 6 tbsp grated Parmesan, divided • 1/4 cup dry red wine • 1 container (15-oz) nonfat ricotta Nutrition Counseling provides: • 1 tsp. dried basil • 3 slices Matzo • 1 tsp. -

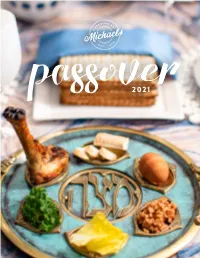

Passover-2021.Pdf

2021 * New Item V Vegetarian N Contains Nuts GF Does Not Contain Gluten Ingredients THANK YOU FOR BEING HERE… The Catering by Michaels Team understands that the holidays look different this year, but the importance of celebrating and being with loved ones (whether in person or virtually) has never been more important. The pandemic has been tough on everyone and especially the hospitality business. We are so thankful for your support, loyalty, and understanding. We look forward to helping you celebrate the holidays and many more celebrations in the future. Health and safety have always been of the utmost importance to us, but it is critical now more than ever that we prioritize health and the way we practice sanitation. Here are the things we are doing to keep you safe: *All employees are subject to a daily health screening before the start of each shift. This includes recording temperatures, checking for symptoms, and completing a series of questions related to COVID-19 and potential exposure. *We are operating our kitchen with two isolated teams who never physically interact. If it becomes necessary for one team to undergo testing or quarantine, the other team can continue working to prepare food safely. * All staff are required to wear the appropriate Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) which includes masks and gloves as well as face shields and disposable aprons when applicable. *Catering by Michaels employees are required to adhere to social distancing guidelines. All food prep areas in our kitchens are stationed at least 6ft apart and floors are marked with arrows and boxes to indicate appropriate distances. -

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday

Full Passover Sedar Meal Sedar Meal Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday March 22, 2021 March 23, 2021 March 24, 2021 March 25, 2021 March 26, 2021 March 27, 2021 March 28, 2021 Breakfast/Dairy Breakfast/Dairy Breakfast/Dairy Breakfast/Dairy Breakfast/Dairy Breakfast/Dairy Breakfast/Dairy Choice of Juice Choice of Juice Choice of Juice Choice of Juice Choice of Juice Choice of Juice Choice of Juice Cream of Wheat Oatmeal Cream of Wheat Peach Baked Oatmeal Cream of Matzo Passover Cold Cereal Passover Cold Cereal Scrambled Eggs Challah French Toast w/ Syrup Cheesy Omelet Vegetarian Sausage Vegetable Cheese Omelet Yogurt & Fruit Parfait Matza Brei Home Fries Cottage Cheese Veg. Bacon Strips Pears Home Fries Passover Cake Potato Latkes Manadarin Oranges Pineapple Bananas Peaches Apricots Alternate Alternate Alternate Alternate Alternate Alternate Alternate French Toast Scrambled Eggs w/ Cheese Waffle w/ Syrup Scrambled Eggs Matzoh Pancakes Hard Boiled Egg Cheese Omelet Available Breakfast Alternates During Passover Fruit and Yogurt Parfait,, Hard Boiled Eggs, Cottage Cheese, Cheese Omelet Juices ( Orange, Apple, Cranberry, Tomato), Coffee and Tea, Low Fat, 2%, Lactaid and Chocolate Milk Lunch/Dairy Lunch/Dairy Lunch/Dairy Lunch/Dairy Lunch/Dairy Lunch/Dairy Lunch/Dairy Minestrone Tossed Salad Vegetarian Lentil Soup Tossed Salad Tossed Salad Romaine Salad Cream of Mushrom Egg Salad Sandwich on Baked Salmon with Tomato Spaghetti Marinara Salmon Cake Mac & Cheese Matzo Lasagna Baked Fish w. Lemon Butter Wheat Butter Fresh