The Symmetry of “Circle Limit IV” and Related Patterns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crystallographic Topology and Its Applications * Carroll K

4 Crystallographic Topology and Its Applications * Carroll K. Johnson and Michael N. Burnett Chemical and Analytical Sciences Division, Oak Ridge National Laboratory Oak Ridge, TN 37831-6197, USA [email protected] http://www. ornl.gov/ortep/topology. html William D. Dunbar Division of Natural Sciences & Mathematics, Simon’s Rock College Great Barrington, MA 01230, USA wdunbar @plato. simons- rock.edu http://www. simons- rock.edd- wdunbar Abstract two disciplines. Since both topology and crystallography have many subdisciplines, there are a number of quite Geometric topology and structural crystallography different intersection regions that can be called crystall o- concepts are combined to define a new area we call graphic topology; but we will confine this discussion to Structural Crystallographic Topology, which may be of one well delineated subarea. interest to both crystallographers and mathematicians. The structural crystallography of interest involves the In this paper, we represent crystallographic symmetry group theory required to describe symmetric arrangements groups by orbifolds and crystal structures by Morse func- of atoms in crystals and a classification of the simplest arrangements as lattice complexes. The geometric topol- tions. The Morse @fiction uses mildly overlapping Gau s- sian thermal-motion probability density functions cen- ogy of interest is the topological properties of crystallo- tered on atomic sites to form a critical net with peak, pass, graphic groups, represented as orbifolds, and the Morse pale, and pit critical points joined into a graph by density theory global analysis of critical points in symmetric gradient-flow separatrices. Critical net crystal structure functions. Here we are taking the liberty of calling global drawings can be made with the ORTEP-111 graphics pro- analysis part of topology. -

Fractal Wallpaper Patterns Douglas Dunham John Shier

Fractal Wallpaper Patterns Douglas Dunham John Shier Department of Computer Science 6935 133rd Court University of Minnesota, Duluth Apple Valley, MN 55124 USA Duluth, MN 55812-3036, USA [email protected] [email protected] http://john-art.com/ http://www.d.umn.edu/˜ddunham/ Abstract In the past we presented an algorithm that can fill a region with an infinite sequence of randomly placed and progressively smaller shapes, producing a fractal pattern. In this paper we extend that algorithm to fill rectangles and triangles that tile the plane, which yields wallpaper patterns that are locally fractal in nature. This produces artistic patterns which have a pleasing combination of global symmetry and local randomness. We show several sample patterns. Introduction We have described an algorithm [2, 4, 6] that can fill a planar region with a series of progressively smaller randomly-placed motifs and produce pleasing patterns. Here we extend that algorithm to fill rectangles and triangles that can fill the plane, creating “wallpaper” patterns. Figure 1 shows a randomly created circle pattern with symmetry group p6mm. In order to create our wallpaper patterns, we fill a fundamental region Figure 1: A locally random circle fractal with global p6mm symmetry. for one of the 17 2-dimensional crystallographic groups with randomly placed, progressively smaller copies of a motif, such as a circle in Figure 1. The randomness generates a fractal pattern. Then copies of the filled fundamental region can be used to tile the plane, yielding a locally fractal, but globally symmetric pattern. In the next section we recall how the basic algorithm works and describe the modifications needed to create wallpaper patterns. -

Congruence Links for Discriminant D = −3

Principal Congruence Links for Discriminant D = −3 Matthias Goerner UC Berkeley April 20th, 2011 Matthias Goerner (UC Berkeley) Principal Congruence Links April 20th, 2011 1 / 44 Overview Thurston congruence link, geometric description Bianchi orbifolds, congruence and principal congruence manifolds Results implying there are finitely many principal congruence links Overview for the case of discriminant D = −3 Preliminaries for the construction Construction of two more examples Open questions Matthias Goerner (UC Berkeley) Principal Congruence Links April 20th, 2011 2 / 44 Thurston congruence link −3 M2+ζ Complement is non-compact finite-volume hyperbolic 3-manifold. Tesselated by 28 regular ideal hyperbolic tetrahedra. Tesselation is \regular", i.e., symmetry group takes every tetrahedron to every other tetrahedron in all possible 12 orientations. Matthias Goerner (UC Berkeley) Principal Congruence Links April 20th, 2011 3 / 44 Cusped hyperbolic 3-manifolds Ideal hyperbolic tetrahedron does not include the vertices. Remove a small hororball. Ideal tetrahedron is topologically a truncated tetrahedron. Cut is a triangle with a Euclidean structure from hororsphere. Matthias Goerner (UC Berkeley) Principal Congruence Links April 20th, 2011 4 / 44 Cusped hyperbolic 3-manifolds have toroidal ends Truncated tetrahedra form interior of a 3-manifold M¯ with boundary. @M¯ triangulated by the Euclidean triangles. @M¯ is a torus. Ends (cusps) of hyperbolic manifold modeled on torus × interval. Matthias Goerner (UC Berkeley) Principal Congruence Links April 20th, 2011 5 / 44 Knot complements can be cusped hyperbolic 3-manifolds Cusp homeomorphic to a tubular neighborhood of a knot/link component. Figure-8 knot complement tesselated by two regular ideal tetrahedra. Hyperbolic metric near knot so dense that light never reaches knot. -

On Three-Dimensional Space Groups

On Three-Dimensional Space Groups John H. Conway Department of Mathematics Princeton University, Princeton NJ 08544-1000 USA e-mail: [email protected] Olaf Delgado Friedrichs Department of Mathematics Bielefeld University, D-33501 Bielefeld e-mail: [email protected] Daniel H. Huson ∗ Applied and Computational Mathematics Princeton University, Princeton NJ 08544-1000 USA e-mail: [email protected] William P. Thurston Department of Mathematics University of California at Davis e-mail: [email protected] February 1, 2008 Abstract A entirely new and independent enumeration of the crystallographic space groups is given, based on obtaining the groups as fibrations over the plane crystallographic groups, when this is possible. For the 35 “irreducible” groups for which it is not, an independent method is used that has the advantage of elucidating their subgroup relationships. Each space group is given a short “fibrifold name” which, much like the orbifold names for two-dimensional groups, while being only specified up to isotopy, contains enough information to allow the construction of the group from the name. 1 Introduction arXiv:math/9911185v1 [math.MG] 23 Nov 1999 There are 219 three-dimensional crystallographic space groups (or 230 if we distinguish between mirror images). They were independently enumerated in the 1890’s by W. Barlow in England, E.S. Federov in Russia and A. Sch¨onfliess in Germany. The groups are comprehensively described in the International Tables for Crystallography [Hah83]. For a brief definition, see Appendix I. Traditionally the enumeration depends on classifying lattices into 14 Bravais types, distinguished by the symmetries that can be added, and then adjoining such symmetries in all possible ways. -

Non-Fundamental Trunc-Simplex Tilings and Their Optimal Hyperball Packings and Coverings in Hyperbolic Space I

Non-fundamental trunc-simplex tilings and their optimal hyperball packings and coverings in hyperbolic space I. For families F1-F4 Emil Moln´ar1, Milica Stojanovi´c2, Jen}oSzirmai1 1Budapest University of Tehnology and Economics Institute of Mathematics, Department of Geometry, H-1521 Budapest, Hungary [email protected], [email protected] 2Faculty of Organizational Sciences, University of Belgrade 11040 Belgrade, Serbia [email protected] Abstract Supergroups of some hyperbolic space groups are classified as a contin- uation of our former works. Fundamental domains will be integer parts of truncated tetrahedra belonging to families F1 - F4, for a while, by the no- tation of E. Moln´aret al. in 2006. As an application, optimal congruent hyperball packings and coverings to the truncation base planes with their very good densities are computed. This covering density is better than the conjecture of L. Fejes T´othfor balls and horoballs in 1964. 1 Introduction arXiv:2003.13631v1 [math.MG] 30 Mar 2020 1.1 Short history Hyperbolic space groups are isometry groups, acting discontinuously on hyperbolic 3-space H3 with compact fundamental domains. It will be investigated some series of such groups by looking for their fundamental domains. Face pairing identifications 2000 Mathematics Subject Classifications. 51M20, 52C22, 20H15, 20F55. Key words and Phrases. hyperbolic space group, fundamental domain, isometries, truncated simplex, Poincar`ealgorithm. 1 2 Moln´ar,Stojanovi´c,Szirmai on a given polyhedron give us generators and relations for a space group by the algorithmically generalized Poincar´eTheorem [4], [6], [11] (as in subsection 1.2). The simplest fundamental domains are 3-simplices (tetrahedra) and their integer parts by inner symmetries. -

The Symmetry of M.C. Escher's Circle Limit IV Pattern and Related Patterns

The symmetry of M.C. Escher’s Circle Limit IV pattern and related patterns. Douglas Dunham Department of Computer Science University of Minnesota, Duluth Duluth, MN 55812-3036, USA E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: http://www.d.umn.edu/˜ddunham/ 1 Two Questions: • What is the correct orientation for the Circle Limit IV pattern? • What is the symmetry group of the Circle Limit IV pattern? 2 What is the correct orientation? Answer: 3 A Sub-question Why aren’t there signatures in all three of the blank devils’ faces next to the central angels? 4 Escher’s Signature (graphic) 5 Escher’s Signature (text) MCE VII-’60 6 Why Examine Orientation Now? • The Symmetries of Things Conway, Burgiel, Goodman Strass A.K. Peters, 2008 • Euclidean and Non-Euclidean Geometries: Devel- opment and History Marvin Greenberg W.H. Freeman, 2008 7 The Symmetries of Things page 224 8 Euclidean and Non-Euclidean Geometries 9 The World of M.C. Escher His Life and Complete Graphic Work (Harry N. Abrams, 1981) • Page 98 (large image): correctly oriented • Page 322 (small image — Catalogue number 436): 10 M.C. Escher web site 11 The Signature 12 Second Question: What is the Symmetry group of Circle Limit IV ? C3? 13 It seems to be D3 14 Escher (in M.C. Escher The Graphic Work Barnes & Noble/TASCHEN 2007 ISBN 0-7607-9669-6, page 10): Here too, we have the components diminishing in size as they move outwards. The six largest (three white angels and three black devils) are arranged about the centre and radiate from it. -

Orbi User Manual 0.5 Orbi User Manual 0.5 Digital Publication

Orbi User Manual 0.5 Orbi User Manual 0.5 Digital Publication Grasshopper Collective Faculty of Architecture Nuremberg Tech Authors: Thomas Alexander Fabian Grohe Leonhard Taglieber Gunnar Tausch User Licence CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Cover Image: Fifteen Wallpaper Groups Contents I. Introduction: Symmetry Groups in Grasshopper II. How Orbi works Programm Structure Data Structure User-Objects Point Groups Wallpaper Groups Spherical Groups Frieze Groups Further work III. References I. Introduction: Symmetry Groups in Grasshopper Orbi is a plug-in for Grasshopper that generates the Orbifold notation and symmetry groups, „The Symmetries patterns parametrically with symmetry groups. of Things“ is a very clear and understandable introduction. Orbi allows to select a symmetry group and define any Symmetry groups are elementary forms of repetition. Un- geometry as the fundamental region of a pattern. The fortunately, however, they appear almost exclusively in the fundamental region is the smallest part that is repeated curriculum of mathematicians. Architects, designers and in a pattern. engineers are often not aware that there is more than point and mirror symmetry. They don´t know that there are diffe- In Orbi the shape of the fundamental region is rent and very specific symmetries possible around a point, displayed and used as drawing area for an input along a line or on a flat or spherically curved surface. And the geometry. The fundamental region can be freely astonishing fact that there are exactly 17 wallpapergroups, 14 arranged and oriented in space. Once the fundamental spherical groups and 7 frieze groups is hardly known among region and the symmetry group are defined, the many people professionally dealing with form. -

Abstracts of Papers Presented at Mathfest 2021 August 4 – August 7, 2021

Abstracts of Papers Presented at MathFest 2021 August 4 – August 7, 2021 1 Contents Alternative Assessments: Lessons from the Pandemic ...........................................................................3 Closing Wallets while Opening Minds: Adopting Open Educational Resources in Mathematics............. 10 Computational Investigation in Undergraduate Mathematics ............................................................... 12 Creating Relevance in Introductory Mathematics Courses ................................................................... 15 Cross-Curricular Applications for Pure Mathematics Courses .............................................................. 18 Ethnomathematics: Culture Meets Mathematics in the Classroom ........................................................ 19 Games in Math Circles ...................................................................................................................... 21 Inquiry-Based Learning and Teaching ................................................................................................ 23 Insights into Quantitative Literacy and Reasoning from the COVID-19 Pandemic ................................ 26 Math In Action ................................................................................................................................. 28 MathArt, ArtMath at MathFest .......................................................................................................... 32 Mathematics and Sports ................................................................................................................... -

Repeating Fractal Patterns with 4-Fold Symmetry Douglas Dunham

Repeating Fractal Patterns with 4-Fold Symmetry Douglas Dunham John Shier Department of Computer Science 6935 133rd Court University of Minnesota, Duluth Apple Valley, MN 55124 USA Duluth, MN 55812-3036, USA [email protected] [email protected] http://john-art.com/ http://www.d.umn.edu/˜ddunham/ Abstract Previously we described an algorithm that can fill a region with an infinite sequence of randomly placed and progressively smaller shapes, producing a fractal pattern. If the algorithm is appropriately modified and the region is a fundamental region for one of the 17 “wallpaper” groups, one can obtain a fractal pattern with that symmetry group. This produces artistic patterns which have a pleasing combination of global symmetry and local randomness. In this paper we focus on such patterns with 4-fold symmetry, and we show several sample patterns. Introduction In the past we have created pleasing patterns with an algorithm [2, 5, 7] that can fill a planar region with a series of progressively smaller randomly-placed motifs. Also we have extended that algorithm to create “wallpaper” patterns with reflection symmetry [3]. In this paper we extend the algorithm to create wallpaper patterns with 4-fold symmetry, i.e. with 4-fold rotation centers. Thus the groups we are interested in are p4,p4mm, and p4mg. Figure 1 shows a random pattern of circles with symmetry group p4. In order to Figure 1: A locally random circle fractal with global p4 symmetry. create our wallpaper patterns, we fill a fundamental region for one of the 2-dimensional crystallographic groups with randomly placed, progressively smaller copies of a motif, possibly with different colors (or orientations), such as the circles of Figure 1. -

Symmetries of Monocoronal Tilings

Symmetries of monocoronal tilings Dirk Frettl¨oh Technische Fakult¨at Universit¨atBielefeld Geometry and Symmetry 29 June - 3 July 2015, Veszpr´em Dedicated to K´arolyBezdek and Egon Schulte on the occasion of their 60th birthdays Dirk Frettl¨oh Symmetries of monocoronal tilings Dirk Frettl¨oh Symmetries of monocoronal tilings 1. Monohedral and isohedral tilings 2. Monogonal and isogonal tilings 3. Monocoronal (and isocoronal) tilings Joint work with Alexey Garber. Dirk Frettl¨oh Symmetries of monocoronal tilings 2 Tiling (=tessellation) covering of R which is also a packing. Pieces (tiles): nice compact sets (squares, triangles...). Dirk Frettl¨oh Symmetries of monocoronal tilings 2 Here: tilings of R . 2 Def.: The symmetry group of a tiling T of R : 2 Sym(T ) = f' isometry in R j '(T ) = T g A central question: Which shapes do tile? 2 I Euclidean plane R d I Euclidean space R (d ≥ 2) 2 I hyperbolic space H I finite regions like 2, 4, ::: Dirk Frettl¨oh Symmetries of monocoronal tilings A central question: Which shapes do tile? 2 I Euclidean plane R d I Euclidean space R (d ≥ 2) 2 I hyperbolic space H I finite regions like 2, 4, ::: 2 Here: tilings of R . 2 Def.: The symmetry group of a tiling T of R : 2 Sym(T ) = f' isometry in R j '(T ) = T g Dirk Frettl¨oh Symmetries of monocoronal tilings Monohedral and isohedral tilings Dirk Frettl¨oh Symmetries of monocoronal tilings Image: isohedral (hence monohedral) tiling. A tiling is called monohedral if all tiles are congruent. A tiling T is called isohedral if its symmetry group acts transitively on the tiles. -

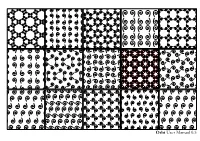

On Periodic Tilings with Regular Polygons

José Ezequiel Soto Sánchez On Periodic Tilings with Regular Polygons AUGUST 11, 2020 phd thesis, impa - visgraf lab advisor: Luiz Henrique de Figueiredo co-advisor: Asla Medeiros e Sá chequesoto.info Con amor y gratitud a... Antonio Soto ∤ Paty Sánchez Alma y Marco Abstract On Periodic Tilings with Regular Polygons by José Ezequiel Soto Sánchez Periodic tilings of regular polygons have been present in history for a very long time: squares and triangles tessellate the plane in a known simple way, tiles and mosaics surround us, hexagons appear in honeycombs and graphene structures. The oldest registry of a systematic study of tilings of the plane with regular polygons is Kepler’s book Harmonices Mundi, published 400 years ago. In this thesis, we describe a simple integer-based representation for periodic tilings of regular polygons using complex numbers. This representation allowed us to acquire geometrical models from two large collections of images – which constituted the state of the art in the subject –, to synthesize new images of the tilings at any scale with arbitrary precision, and to recognize symmetries and classify each tiling in its wallpaper group as well as in its n-uniform k-Archimedean class. In this work, we solve the age old problem of characterizing all triangle and square tilings (Sommerville, 1905), and we set the foundations for the enumeration of all periodic tilings with regular polygons. An algebraic structure for families of triangle-square tilings arises from their representation via equivalence with edge-labeled hexagonal graphs. The set of tilings whose edge-labeled hexagonal dual graph is embedded in the same flat torus is closed by positive- integer linear combinations. -

Tegula- Exploring a Galaxy of Two-Dimensional Periodic Tilings

Tegula- exploring a galaxy of two-dimensional periodic tilings R¨udigerZeller Olaf Delgado Friedrichs Daniel H. Huson July 2020 Abstract Periodic tilings play a role in the decorative arts, in construction and in crystal structures. Com- binatorial tiling theory allows the systematic generation, visualization and exploration of such tilings of the plane, sphere and hyperbolic plane, using advanced algorithms and software. Here we present a \galaxy" of tilings that consists of the set of all 2.4 billion different types of periodic tilings that have Dress complexity up to 24. We make these available in a database and provide a new program called Tegula that can be used to search and visualize such tilings. Availability: All tilings and software and are open source and available here: https://ab.inf.uni-tuebingen.de/software/tegula. 1 Introduction Two dimensional periodic tilings play a role in the decorative arts, prominent examples being the euclidean tilings that cover the Alhambra palace in Granada, Spain, and M.C. Escher's illustrations of euclidean, hyperbolic and spherical tilings involving reptiles, birds and other shapes (Schattschneider, 2010). Two dimensional euclidean tilings are used in the construction of floors, walls and roofs. Hyperbolic tilings are used in the analysis of minimal surfaces of three-dimensional crystal structures (Ramsden et al., 2009; Kolbe and Evans, 2018). A two-dimensional periodic tiling (T ; Γ) of the euclidean plane, sphere or hyperbolic plane, consists of a set of tiles T and a discrete group Γ of symmetries of T with compact fundamental domain, see Figure 1. Combinatorial tiling theory, based on the encoding of periodic tilings as \Delaney-Dress symbols" (Dress, 1984, 1987; Dress and Huson, 1987), can be used to systematically enumerate all possible (equivariant) types of two-dimensional tilings by their curvature and increasing number of equivalence classes of tiles (Huson, 1993).