Christmas Miracle at Moose Factory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Fall-Rose City Beacon

R se City Beacon U.S. Coast G uard Auxiliary Flotilla 091 -22 -05, Jackson, Mich igan Fall 2016 Flotilla Activities: Attendance at the event was high, with the flotilla members seeing about 2,500 peo- July –September ple on Thursday and another 2,200 on Friday. AIM Week Academy Admissions Partners Kim Cole and Jan Osborn participated in AIM Week in July this year, providing logistical support to the program. The Academy Introduction Mis- sion (AIM) program is held each year by the U.S. Coast Guard Academy in New London, Connecticut. During AIM, students who are about to enter their senior year of high school are exposed to six days of life as an Academy cadet. Vessel Exams in Cajun Country Thom Brennan, FSO-PB Last year, I hadn’t completed the five ves- sel safety checks needed to keep my vessel examiner qualifications current. Accordingly, this year I found myself in REYR status (failure to meet currency). Since I live in Louisiana, commuting to Michigan to participate in the flotilla’s VE Blitzes was out of the question. I contacted Edie Wellemeyer, the FC of Flotilla 081-04-04 in Lafayette, Louisiana. Edie graciously invited me to help them out on their JACKSON, July 14 —Coastie the Safety Boat next ramp day. This would allow me to com- heads out on patrol during the Learning Fair. plete the two supervised visits required to get Coastie was operated by Mark Cole. myself out of REYR status. Located about two hours west of New Orleans, Lafayette is the Learning Fair capital of Cajun Country in Louisiana. -

{PDF} the Gamemaker Standard Ebook, Epub

THE GAMEMAKER STANDARD Author: David Vinciguerra Number of Pages: 276 pages Published Date: 14 Dec 2015 Publisher: Taylor & Francis Ltd Publication Country: London, United Kingdom Language: English ISBN: 9781138856974 DOWNLOAD: THE GAMEMAKER STANDARD The GameMaker Standard PDF Book Convex Sets and Their ApplicationsWhat motives underlie the ways humans interact socially. And if nothing else, I knew how to deal with feelings. Unlike a generation of young writers who lost faith in the God of the Bible, Tolkien and Lewis produced epic stories infused with the themes of guilt and grace, sorrow and consolation. There have been major developments in our understanding and management of COPD over the last decade and this new edition has extensively reviewed the known literature and latest Guidelines to provide the most up to date and comprehensive picture of diagnosis, investigation and best patient care and management. Since Adam first hid his nakedness from God and pointed the finger at Eve, men have struggled to take responsibility for their sexuality. A Better Life: How Our Darkest Moments Can be Our Greatest GiftAnabolic steroids have traditionally been controversial in the sporting arena. Law of Estate AgencyEvolution of Water Supply Through the Millennia presents the major achievements in the scientific fields of water supply technologies and management throughout the millennia. Help with the pronunciation of Chinese words, including Pinyin for all Chinese headwords, translations, phrases and examples. The question. How to Choose the Right Plugins for your WordPress Website. Here too is the poignant and compelling history of Siegel and Shuster s lifelong struggle for the recognition and rewards rightly due to the architects of a genuine cultural phenomenon. -

First Flights

:.:'.•lllllllllllllClllllllllllllrlllllllllllllClllllllllllllrlllllllllllllClllllllllllllrlllllllllllllClllllllllllllrlllllllllllllClllllllllllllrlllllllllllllClllllllllllllCllllllllll~• " ~ I" I~ I We are philatelic auctioneersl_ c= and specialize c ; . I ~ m providing i " a competitive market ~ for stamp collections and other philatelic properties I I ~ Over ·30 years experience i assures the maximum in results Your inquiry is welcomed I I IRWIN HEI JIAN~ I Inc. !==.=====:::. Serving American Philately Since 1926 - :..: 2 WEST 46th STREET £ NEW YORK 36, N.Y. Telephone: JUdson 2-2393 Suite 708 ~lllllllllClllllllllllllClllllllllllllrlllllllllllllClllllllllllllClllllllllllllClllllllllllllClllllllllllllClllllllllllllClllllllllllllClllllllllllllClll1111111111ClHllllllllllC•~ AUGUST, 1961 The American Air Mail Society A Non-Profit Corporation Incorporated 1944 Organized 1923 Under the Laws ~IJGff~Ic~ of Ohio \j PRESIDENT Official Publication of the Robert W. Murch AMERICAN AIR MAIL SOCIETY 9560 Litzinger Road St. Louis 24, Mo. SECRETARY Ruth T. Smith VOL. 32 No. 11 ISSUE No. 375 102 Arbor Road Riverton, New Jersey '.l'REASURER John J. Smith Contents .............. for August, 1961 102 Arbor Road Riverton, New Jersey A.A.M.S. Election Results ···---················ 334 VICE-PRESIDENTS 1961 ConvenUon Committee Announced 335 Joseph L. Eisendrath Proposed Convention Schedule ............ 335 Louise S. Hoffman Florence L. Kleinert The Navy Carries the Mail .................... 337 Dr. Southgate Leigh, Jr. The New 11-Cent Aerogramme ·····---···· -

Commander Elmer F. “Archie” Stone, Uscg

COMMANDER ELMER F. “ARCHIE” STONE, USCG COAST GUARD AVIATOR #1 by Captain Robert B. Workman, Jr. USCG (Retired) Coast Guard Aviator # 914, Helicopter Pilot # 438 1887 - 1936 INTRODUCTION: The birth of aviation and events in WWI and WWII inspired a few visionary men from each of the armed services and civil aviation. They knew each other, and many were close friends. Among many, the list includes Glenn Curtiss, Captain Eddie Rickenbaker (famous WWI leading ACE), aircraft designers Fokker, Sikorsky and de Seversky, RADM W.A. Moffett, USN, CDR J.H. Towers, USN (Naval Aviator #3), Prince of Wales and CDR Elmer F. Stone, USCG (Coast Guard Aviator #1)1 An additional catalyst occurred when the Coast Guard was transferred to the Department of the Navy during both wars, and Coast Guard officers were assigned to Navy ships and aviation units. The Navy was introduced to Coast Guard aviators with different visions and capabilities that grew from operations in heavy seas and foul weather during Search and Rescue missions. It was therefore natural that the early days of Naval Aviation were marked with extraordinary coordination and mutual cooperation between the Navy and the Coast Guard. Early aviators in both services supported each other while convincing skeptical shipboard officers of the relevance aircraft had for service operations. Aircraft loaned to the Coast Guard by the Navy, aviator training at NAS Pensacola and Coast Guard aviators assigned to Navy aviation projects were not uncommon. This is the story of a preeminent member of this proud family, Elmer Fowler Stone, who during one assignment served as Chief Test Pilot for Seaplanes in the Navy’s Aviation Division of NC aircraft, and later was the pilot of NC-4. -

Vol. 59, No. 6 23 a Reserve Unit

from their guns, while a squadron of Portuguese airplanes Commander: escorted the NC-4 on its arriTal to Lisbon. A navy boat Commander (USN) John H. Towers (NC-3, Squadron took Lieutenant Commander Read and his crew from Commander) NC-4 to USS Rochester to receive a hero’s welcome Lieutenant Commander (USN) Albert Cushing Read (NC-4, Commander) from United States Navy and Portuguese officials. In Lieutenant Commander (USN) Patrick N. L. Bellinger addition, a popular festival also took place to honor the (NC- 1, Pilot) achievement of the crew of NC-4. Officer: As a signal of respect for the new flying navigators, Commander (USN) Holden B. Richardson (NC-3, Portugal, an old maritime nation, and full of examples of Pilot) historic navigation episodes, granted to all three seaplanes Lieutenant Commander (USN) Marc Andrew Mitscher crewmembers (and another United States Navy Rear (NC- 1, Pilot) Admiral), her most important decoration - the Military Order of the Tower and the Sword (Figure 9).2 The crew Knight: Lieutenant Commander (USN) Robert A. Lavender of the NC-4 then proceeded to take off for Plymouth, (NC-3, Radio Operator) England and anived on May 31 st. Lieutenant (USN) David H. McCulloch (NC-3, Co- pilot) Boatswain (USN) Lloyd R. Moore (NC-1, Engineer) Lieutenant (USCG) Elmer Fowler Stone (NC-4, Pilot) Lieutenant (USN) Walter Hinton (NC-4, Co-pilot) Lieutenant (USN) James L. Breese (NC-4, Reserve Pilot) Ensign (USN) Herbert C. Rodd (NC-4, Radio Operator) Chief Special Machinist (USN) Eugene S. Rhoades (NC-4, Engineer) Lieutenant (USN) Louis T. -

100 YEARS of SUSTAINED POWER FLIGHT HISTORY Compiled By

100 YEARS OF SUSTAINED POWER FLIGHT HISTORY Compiled By: Barbara Harris-Para Before the Wright Brothers experience there were attempts for men/women to fly: 1793 A French balloonist, Jean Pierre Blanchard, became the first aeronaut in America. He ascended from Phila. & 45 minutes later landed in Deptford, NJ 1830 Charles F. Durant of Jersey City was America’s 1st native-born aeronaut. He flew his balloon from Castle Garden (Battery Park) in Manhattan & landed in South Amboy, NJ 1863 Perth Amboy’s Dr. Solomon Andrews built & flew America’s 1st dirigible balloon. With a rudder but no engine the doctor flew his invention from NJ to Long Island by tacking in the cross winds like a sailboat. 1903 December 17th Kitty Hawk, NC Orville Wright makes the first controlled powered flight, flying the “Wright Flyer” 120’ in 12 seconds 1905 Mrs. Hart O. Berg flew with Wilbur Wright, just two years after Wright’s historic flight 1906 Brazilian Alberto Santos Dumont publicly flew a powered aircraft in Europe in his 14-bis plane First Aero Exhibition, the NY Aero Show held with the auto show 1907 International Aeronautic Congress held in New York 1908 Glenn H. Curtiss finished his plane the “June Bug biplane”. It was flown on March 12, for 300’, he then improved upon it, flew it on July 4 over a measured kilometer First Flying Club established in New York City, “Aeronautical Society” 1909 First private airplane sold in U.S. a pusher sold to the Aeronautic Society of New York First Aeroplane dealership- Wycroff, Church & Partridge, auto dealers in NYC, acquired Curtiss line Dr. -

Zeppelins & Aerophilately

Zeppelins & Aerophilately Afghanistan 11556 1931 Zeppelin Flight w/ B87 - B92 A Brief Note complete Rotary Set ..................... $1,000.00 07931 1933 4th South American Flight. Sent via 11557 1931 Zeppelin Flight w/ B87 - B92 Turkey to Brazil (S.223 B) ........... $3,900.00 complete Rotary Set ..................... $1,000.00 We are pleased to offer you our new listing 11558 1931 Zeppelin Flight w/ B87 -B92 Albania Complete Rotary Set ....................... $600.00 of Zeppelins and Aerophilately. This 11555 1931 Zeppelin Flight w/ B89, B90, B92 list is only a small part of our 12046 C36 - C42 LH / NH C40 - C42 NH cv 11.00 Rotary ............................................. $750.00 as H .................................................. $60.00 Aerophilately stock. If you don’t see 03039 1932 (June 22) Catapult cover "Europa" to 12051 C8 - C14 F - VF LH + NH Slight toning cv New York sent by registered mail to Costa what you are looking for - please 39.50 ................................................. $25.00 Rica. Stamped "Received in ordinary mail ask! Strongest in Worldwide Algeria N.Y.P.O. Varick S" Backstamped Berlin, Zeppelin flights, this list includes New York and Costa Rica on reverse. 07934 1933 2nd South American Flight sent to K111AU cv $800.00 Hab. 89 .......... $750.00 rarities as well as U.S. and Brazil S.214Aa ................................ $575.00 08138 1934 "Bremen" Catapult Registered. Worldwide DO-X, Balbo flights, etc. Postage paid in cash. (k207cAV $900) 8 Antigua carried ............................................. $650.00 As items are virtually all are one-of- 13108 1936 (May 2) Hindenburg 1st North a-kind, we suggest ordering early to 12720 1931(Aug 20) special flight Do-X to San America flight cover to NY. -

Apj Ads Buy Sell Want Lists

AAMS EXCHANGE DEPARTMENT APJ ADS BUY SELL WANT LISTS RATES: AEROGRAMMES - Have duplicates to FOUR CENTS PER WORD per insertion. exchange or sell. These include the scarce •\IIinimum charge one dollar. Remittance South African and Korean military sheets . must accompany order and copy. The Richard P. Heffner, 2012 Spring Street, AIRPOST JOURNAL. 350 No. Deere Park West Lawn, Penna. *372 Drive, Highland Park, Ill. EXCHANGE WANTED - Postally us2d 6 3/4 AIRMAIL ENVELOPES, Barber Pole Aerograms UN. M.L Position Blocks. 1st design, 24 lb. Parchment Stock, 100% Rag day. Dr. Keller., Sr., Hilton, N. Y. *371 Content. Prices and Samples Ten Cents. Milton Ehrlich, 34-15A 31st Ave., Long Is OFFERING St. Lawrence Seaway land City 6, N. Y. Member A.A.M.S. 372 Souvenir Wooden Money (2). Want Plate Block Be Champion, or three 4c Commem. YOU OWE it to yourself to join Airmails Plates. John Kitchen, Route 6, 'Voodstock, Exclusively. No cash fees for next sixty Ontario, Canada. *371 days. Join now. Airmails Exclusively, ---· ·----------------- 1757 Henderson St., Chicago 13, 11. *371 50-4c U.S. Mint Comm. will bring you regular 200 kit of Phila-Tex cellulose ace FOREIGN Used Airmail Stamp, Single3 tate for making your own mounts. Ar and Complete sets on and off covers, better, 5319 N. Bernard, Chicago 25, Ill. Want list filled, Price list free. H/R Stamp Co., Box 89-N Long Beach, N. Y. *3'/2 ANTARCTIC Covers: Exchange ship for ship, base for base, flown cover for flown SCOTT #369 - 2c Lincoln 1909, bluish oa cover. Bill S9hneider, Metuchen, New per, very fine to superb. -

A Companion to Capitola 11-18

A Companion To Capitola By Frank Perry Capitola Historical Museum 2018 A Companion To Capitola Published by the Capitola Historical Museum 410 Capitola Avenue Capitola, CA. 95010 Capitola Museum Board of Trustees, Spring, 2020 Niels Kisling, president; David Peyton, vice president; Pamela Greeninger, secretary; Brian Legakis, treasurer; Joshua Henshaw, youth representative; Emmy Mitchell-Lynn; Dean Walker; Gordon van Zuiden Cover: A portion of the mural “Our Capitola” by Jon Ton and Maia Negre Funded by the Capitola Art and Cultural Commission 2015 Fifth printing with minor revisions, 2020 Copyright 2018 Board of Trustees Capitola Historical Museum !2 A Companion To Capitola Introduction At the Capitola Historical Museum, we are asked hundreds of questions each year about Capitola. Many visitors want to know certain dates, such as when Capitola was incorporated or when the railroad trestle was built. Others are curious about people, places, or historic buildings. This publication is an attempt to answer many of those questions in the form of a quick reference guide. It includes people, places, events, agricultural products, natural features, public art, schools, parks, churches, books about Capitola, movies made in Capitola, and assorted other topics. Each entry includes a brief description and significant dates. Many entries also include a reference to the source of the information and/or further reading. Some entries are based on information from multiple sources, of which only one or two are listed. Emphasis is on the historical development of Capitola. This list does not include living people, and it does not include businesses that started after 1980. If a word in a description has its own entry, it is often in bold. -

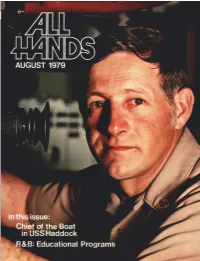

Chief of the Boat in USS Haddock -I

1. "I -i 1 ! Chief of the Boat in USS Haddock WB: Educational .. I No other way to go. When your ship is named afer the man with the most famous signature of all time (at least for Ameri- cans), what better way to display the name than on the stern? Commander Ron Wilgenbusch.first commanding ogicer of the new destroyer USS John Hancock (DD 981). had his ship's name done up in style before commissioning at Pascagoula. Miss. (Litton photo.) .I . MAGAZINE OF THE U.S. NAVY - 57th YEAR OF PUBLICATION AUGUST 1979 NUMBER 751 Chief of Naval Operations: ADM Thomas B. Hayward Chief of Information: RADM David M. Cooney OIC Navy Internal Relations Act: CAPT Robert K. Lewis Jr. Features 6 NATICK-THE NAVY'S CLOTHING 'THINK TANK' Seeking better ways to improve protective clothing 13 ONLY RETIREMENT ENDED HIS CAREER Carl Brashear believes there's no such thing as the impossible 16 CHIEF OF THE BOAT-LEADERSHIP MAKES THE DIFFERENCE A look at a submarine's most knowledgeable enlisted man 20 THERE'S SOMETHING FOR EVERYONE ON ELEUTHERA The pace is less hectic and people have fewer worries 22 DUTY IN THE 'YARD' The overview of life at Annapolis for junior officers is positive 30 7TH FLEET BAND 'DOWN UNDER' Sydney responds to the Navy's versatile Far East Edition Page 22 36 WALTER HINTON- WALKING TEXTBOOK ON EARLY FLIGHT At 90, he recalls the birth of aviationas though it happened yesterday 42 EDUCATION AND TRAINING Ninth in aseries on Rights and Benefits 2 Currents 28 Bearings 48 Mail Buoy Covers Front: EMCM(SS) Arthur "Buck" Parker, Chief of the Boat of USS Haddock (SSN 62 1 ).