Baltimore's East-West Expressway and the Construction of the "Highway to Nowhere." (338 Pp.)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jewell Chambers Transcript

COPYRIGHT / USAGE Material on this site may be quoted or reproduced for personal and educational purposes without prior permission, provided appropriate credit is given. Any commercial use of this material is prohibited without prior permission from The Special Collections Department - Langsdale Library, University of Baltimore. Commercial requests for use of the transcript or related documentation must be submitted in writing to the address below. When crediting the use of portions from this site or materials within that are copyrighted by us please use the citation: Used with permission of the University of Baltimore. If you have any requests or questions regarding the use of the transcript or supporting documents, please contact us: Langsdale Library Special Collections Department 1420 Maryland Avenue Baltimore, MD 21201-5779 http://archives.ubalt.edu The University of Baltimore is launching a two-year investigation called “Baltimore’68: Riots and Rebirth,” a project centered around the events that followed the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and their effects on the development of our city. UB administration and faculty members in the law school and in the undergraduate departments of history and community studies are planning a series of projects and events to commemorate the 40th anniversary of this pivotal event. We are currently working with the Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History, The Jewish Museum of Maryland, Maryland Public Television and the Enoch Pratt Free Libraries to pursue funding for projects that may include conferences, a website and a library traveling exhibit. Your potential participation in an oral history project would contribute to the very foundation of this project – the memories of Baltimoreans who lived through the riots and saw the changes that came about in response to them. -

Entire Public Libraries Directory In

October 2021 Directory Local Touch Global Reach https://directory.sailor.lib.md.us/pdf/ Maryland Public Library Directory Table of Contents Allegany County Library System........................................................................................................................1/105 Anne Arundel County Public Library................................................................................................................5/105 Baltimore County Public Library.....................................................................................................................11/105 Calvert Library...................................................................................................................................................17/105 Caroline County Public Library.......................................................................................................................21/105 Carroll County Public Library.........................................................................................................................23/105 Cecil County Public Library.............................................................................................................................27/105 Charles County Public Library.........................................................................................................................31/105 Dorchester County Public Library...................................................................................................................35/105 Eastern -

Rede Record Brazil's 'Os Dez Mandamentos': You Still Haven't Seen It All

Rede Record Brazil's 'Os Dez Mandamentos': You Still Haven't Seen It All 04.04.2016 Regarded as the great sensation of Brazilian television, the biblical telenovela Os Dez Mandamentos (The Ten Commandments), returns for a second season, with a warning: you still haven't seen it all. The series, penned by Vivian de Oliveira, will premiere Monday, April 4, at 8:30 p.m. on Rede Record Brazil. The channel - considered Brazil's second-largest producer of original content with a total of more than 90 hours per week - offers programming focused on the Brazilian family. The novela's first season was exported to Argentina, where it aired on Telefe in prime time, becoming the country's most-watched program in its debut, scoring a 14.9 household ratings average. Also, the production has been turned into a film, where it became the second biggest box-office hit in the history of Brazilian cinema. The launch campaign for the show's second season builds on this phenomenon. "The great secret behind the excellent results obtained by The Ten Commandments has been selling the product as a telenovela, and not as a biblical story," says Alexandre Barbosa Machado de Souza, on-air creative promos coordinator for Rede Record. This is why since season one the communication strategy has focused "more on the plot than the biblical aspects, including the romances, the conflicts, the betrayals and the drama that all major soap operas have," Souza says. As for the show's Biblical origins, Marcelo Caetano, programming director of Rede Record, says "we have been producing this type of content since 2010. -

The Life of Moses #25 February 2, 2020

The Life of Moses #25 February 2, 2020 “The 10 Plagues upon Egypt” Part 5 Exodus 7-12 Introduction: Tonight, we return to the first of the ten plagues which God brought upon Egypt. This plague consisted of the water being turned into blood. This beginning of plagues would have been devastating to the Egyptians. The Nile River was the lifeline which flowed through the land. Let me review the points which we looked at last week. 1. The Reproving before the Plague Notice Exodus 7:14-16 Pharaoh was given fair warning before the plague. We considered this thought before, but I will remind you again that God always brings a warning before His judgment falls. 2. The Revelation in the Plague Notice Exodus 7:17 One of the purposes of all the plagues would be to educate the people of Egypt and Israel about God. 3. The Ruin of the Plague. Notice Exodus 7:19-21 This plague was devasting to the Egyptians. The river waters and the ponds were all turned to blood. It would affect three areas of their lives: 1. Their food supplies. 2. Their environment. 3. Their economy. Egypt was desert country. They depended completely upon the Nile for irrigation as well as soil to put upon their fields. Most of Egypt’s trade and commerce depended upon the Nile River. This plague was a great blow to every area in Egypt. 4. The Reaping of the Plague. This plague of water to blood brought upon Egypt was the reaping of that which they were guilty of in the past. -

Green V. Garrett: How the Economic Boom of Professional Sports Helped to Create, and Destroy, Baltimore's

Green v. Garrett: How the Economic Boom of Professional Sports Helped to Create, and Destroy, Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium 1953 Renovation and upper deck construction of Memorial Stadium1 Jordan Vardon J.D. Candidate, May 2011 University of Maryland School of Law Legal History Seminar: Building Baltimore 1 Kneische. Stadium Baltimore. 1953. Enoch Pratt Free Library, Baltimore. Courtesy of Enoch Pratt Free Library, Maryland’s State Library Resource Center, Baltimore, Maryland. Table of Contents I. Introduction........................................................................................................3 II. Historical Background: A Brief History of the Location of Memorial Stadium..............................................................................................................6 A. Ednor Gardens.............................................................................................8 B. Venable Park..............................................................................................10 C. Mount Royal Reservoir..............................................................................12 III. Venable Stadium..............................................................................................16 A. Financial History of Venable Stadium.......................................................19 IV. Baseball in Baltimore.......................................................................................24 V. The Case – Not a Temporary Arrangement.....................................................26 -

NORTH Highland AVENUE

NORTH hIGhLAND AVENUE study December, 1999 North Highland Avenue Transportation and Parking Study Prepared by the City of Atlanta Department of Planning, Development and Neighborhood Conservation Bureau of Planning In conjunction with the North Highland Avenue Transportation and Parking Task Force December 1999 North Highland Avenue Transportation and Parking Task Force Members Mike Brown Morningside-Lenox Park Civic Association Warren Bruno Virginia Highlands Business Association Winnie Curry Virginia Highlands Civic Association Peter Hand Virginia Highlands Business Association Stuart Meddin Virginia Highlands Business Association Ruthie Penn-David Virginia Highlands Civic Association Martha Porter-Hall Morningside-Lenox Park Civic Association Jeff Raider Virginia Highlands Civic Association Scott Riley Virginia Highlands Business Association Bill Russell Virginia Highlands Civic Association Amy Waterman Virginia Highlands Civic Association Cathy Woolard City Council – District 6 Julia Emmons City Council Post 2 – At Large CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS VISION STATEMENT Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION 1:1 Purpose 1:1 Action 1:1 Location 1:3 History 1:3 The Future 1:5 Chapter 2 TRANSPORTATION OPPORTUNITIES AND ISSUES 2:1 Introduction 2:1 Motorized Traffic 2:2 Public Transportation 2:6 Bicycles 2:10 Chapter 3 PEDESTRIAN ENVIRONMENT OPPORTUNITIES AND ISSUES 3:1 Sidewalks and Crosswalks 3:1 Public Areas and Gateways 3:5 Chapter 4 PARKING OPPORTUNITIES AND ISSUES 4:1 On Street Parking 4:1 Off Street Parking 4:4 Chapter 5 VIRGINIA AVENUE OPPORTUNITIES -

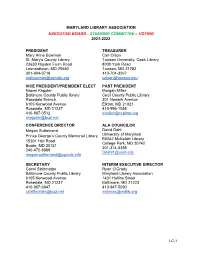

MLA Organizational Structure

MARYLAND LIBRARY ASSOCIATION EXECUTIVE BOARD - STEERING COMMITTEE – VOTING 2021-2022 PRESIDENT TREASURER Mary Anne Bowman Carl Olson St. Mary’s County Library Towson University, Cook Library 23630 Hayden Farm Road 8000 York Road Leonardtown, MD 20650 Towson, MD 21252 301-904-0718 410 - 704 - 3267 [email protected] [email protected] VICE PRESIDENT/PRESIDENT ELECT PAST PRESIDENT Naomi Keppler Morgan Miller Baltimore County Public library Cecil County Public Library Rosedale Branch 301 Newark Avenue 6105 Kenwood Avenue Elkton, MD 21921 Rosedale, MD 21237 410 - 996 - 1055 410-887-0512 [email protected] [email protected] CONFERENCE DIRECTOR ALA COUNCILOR Megan Sutherland David Dahl Prince George’s County Memorial Library University of Maryland B0242 McKeldin Library 15301 Hall Road College Park, MD 20742 Bowie, MD 20721 301-314-0395 240-472-8889 [email protected] [email protected] SECRETARY INTERIM EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Conni Strittmatter Ryan O’Grady Baltimore County Public Library M ary land Library Association 6105 Kenwood Avenue 1401 Hollins Street Rosedale, MD 21237 Baltimore, MD 21223 410-887-6047 410 - 947 - 5090 [email protected] [email protected] I-C-1 EXECUTIVE BOARD – APPOINTED OFFICERS - VOTING 2021-2022 PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT LEGISLATIVE Tyler Wolfe Andrea Berstler Baltimore County Public Library Carroll County Public Library 3202 Bayonne Avenue 1100 Green Valley Road Baltimore, MD 21214 New Windsor, MD 21776 410-905-6866 443-293-3136 cell: 443-487-1716 [email protected] [email protected] INTELLECTUAL FREEDOM Andrea -

Narrative Epic and New Media: the Totalizing Spaces of Postmodernity in the Wire, Batman, and the Legend of Zelda

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-17-2015 12:00 AM Narrative Epic and New Media: The Totalizing Spaces of Postmodernity in The Wire, Batman, and The Legend of Zelda Luke Arnott The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Nick Dyer-Witheford The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Media Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Luke Arnott 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Other Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Arnott, Luke, "Narrative Epic and New Media: The Totalizing Spaces of Postmodernity in The Wire, Batman, and The Legend of Zelda" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3000. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3000 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NARRATIVE EPIC AND NEW MEDIA: THE TOTALIZING SPACES OF POSTMODERNITY IN THE WIRE, BATMAN, AND THE LEGEND OF ZELDA (Thesis format: Monograph) by Luke Arnott Graduate Program in Media Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Luke Arnott 2015 Abstract Narrative Epic and New Media investigates why epic narratives have a renewed significance in contemporary culture, showing that new media epics model the postmodern world in the same way that ancient epics once modelled theirs. -

A Guide to the Records of the Mayor and City Council at the Baltimore City Archives

Governing Baltimore: A Guide to the Records of the Mayor and City Council at the Baltimore City Archives William G. LeFurgy, Susan Wertheimer David, and Richard J. Cox Baltimore City Archives and Records Management Office Department of Legislative Reference 1981 Table of Contents Preface i History of the Mayor and City Council 1 Scope and Content 3 Series Descriptions 5 Bibliography 18 Appendix: Mayors of Baltimore 19 Index 20 1 Preface Sweeping changes occurred in Baltimore society, commerce, and government during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. From incorporation in 1796 the municipal government's evolution has been indicative of this process. From its inception the city government has been dominated by the mayor and city council. The records of these chief administrative units, spanning nearly the entire history of Baltimore, are among the most significant sources for this city's history. This guide is the product of a two year effort in arranging and describing the mayor and city council records funded by the National Historical Publications and Records Commission. These records are the backbone of the historical records of the municipal government which now total over three thousand cubic feet and are available for researchers. The publication of this guide, and three others available on other records, is preliminary to a guide to the complete holdings of the Baltimore City Archives scheduled for publication in 1983. During the last two years many debts to individuals were accumulated. First and foremost is my gratitude to the staff of the NHPRC, most especially William Fraley and Larry Hackman, who made numerous suggestions regarding the original proposal and assisted with problems that appeared during the project. -

The NAACP and the Black Freedom Struggle in Baltimore, 1935-1975 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillm

“A Mean City”: The NAACP and the Black Freedom Struggle in Baltimore, 1935-1975 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By: Thomas Anthony Gass, M.A. Department of History The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Hasan Kwame Jeffries, Advisor Dr. Kevin Boyle Dr. Curtis Austin 1 Copyright by Thomas Anthony Gass 2014 2 Abstract “A Mean City”: The NAACP and the Black Freedom Struggle in Baltimore, 1935-1975” traces the history and activities of the Baltimore branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) from its revitalization during the Great Depression to the end of the Black Power Movement. The dissertation examines the NAACP’s efforts to eliminate racial discrimination and segregation in a city and state that was “neither North nor South” while carrying out the national directives of the parent body. In doing so, its ideas, tactics, strategies, and methods influenced the growth of the national civil rights movement. ii Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the Jackson, Mitchell, and Murphy families and the countless number of African Americans and their white allies throughout Baltimore and Maryland that strove to make “The Free State” live up to its moniker. It is also dedicated to family members who have passed on but left their mark on this work and myself. They are my grandparents, Lucious and Mattie Gass, Barbara Johns Powell, William “Billy” Spencer, and Cynthia L. “Bunny” Jones. This victory is theirs as well. iii Acknowledgements This dissertation has certainly been a long time coming. -

Countywide Bus Rapid Transit Study Consultant’S Report (Final) July 2011

Barrier system (from TOA) Countywide Bus Rapid Transit Study Consultant’s Report (Final) July 2011 DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION COUNTYWIDE BUS RAPID TRANSIT STUDY Consultant’s Report (Final) July 2011 Countywide Bus Rapid Transit Study Table of Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. ES-1 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Key additional elements of BRT network ...................................................................... 2 1.1.1 Relationship to land use ........................................................................................ 2 1.1.2 Station access ...................................................................................................... 3 1.1.3 Brand identity ........................................................................................................ 4 1.2 Organization of report .................................................................................................. 5 1.3 Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................ 5 2 Study Methodology ............................................................................................................. 7 2.1 High-level roadway screening ...................................................................................... 9 2.2 Corridor development and initial -

Maintenance Surface Treatment (MST) Paving Program, April 13, 2010

Maine State Library Digital Maine Transportation Documents Transportation 4-13-2010 MaineDOT Region 2 : Maintenance Surface Treatment (MST) Paving Program, April 13, 2010 Maine Department of Transportation Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalmaine.com/mdot_docs Recommended Citation Maine Department of Transportation, "MaineDOT Region 2 : Maintenance Surface Treatment (MST) Paving Program, April 13, 2010" (2010). Transportation Documents. 1381. https://digitalmaine.com/mdot_docs/1381 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Transportation at Digital Maine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Transportation Documents by an authorized administrator of Digital Maine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MaineDOT 2010 Maintenance Surface Treatment (MST) Paving Program MaineDOT Map ID Municipalities Anticipated Road Segment Description Miles Region # Affected 2010 Dates Route 105 - from the southerly junction of Routes 131 and 105, 2 21 Appleton, Hope 11.34 8/2 - 10/1 extending southerly to the Camden/Hope town line Route 100 - from 1.84 miles east of the Benton/Fairfield town line to 2 17 Benton 2.95 9/8 - 9/21 0.47 mile westerly of the Benton/Clinton town line Turner/Biscay Road - from the junction with Biscay Road, Bremen 2 16 Bremen 3.04 8/2 - 10/1 to the junction with Route 32, Bremen Route 139 - from the intersection of Route 137/7 in Brooks, 2 114 Brooks, Knox 8.78 6/28 - 8/13 extending northerly to the junction of Routes 139 and 220 Weeks Mills Road - from the intersection of