Subli: on the Use of Multidisciplinal Methods in Musicology Elena Rivera Mirano

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL REPORT JULY 2011 -JULY 2012 Unit 601, DMG Center, 52 Domingo M

BISHOPS-BUSINESSMEN’S CONFERENCE for Human Development ANNUAL REPORT JULY 2011 -JULY 2012 Unit 601, DMG Center, 52 Domingo M. Guevarra St. corner Calbayog Extension Mandaluyong City Tel Nos. 584-25-01; Tel/Fax 470-41-51 E-mail: [email protected] Website: bbc.org.ph TABLE OF CONTENTS BISHOPS-BUSINESSMEN’S CONFERENCE MESSAGE OF NATIONAL CO-CHAIRMEN.....................................................1-2 FOR HUMAN DEVELOPMENT NATIONAL EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE ELECTION RESULTS............................ 3-4 STRATEGIC PLANNING OF THE EXCOM - OUTPUTS.....................................5-6 NATIONAL EXECUTIVE COMMITEE REPORT.................................................7-10 NATIONAL SECRETARIAT National Greening Program.................................................................8-10 Consultation Meeting with the CBCP Plenary Assembly........................10-13 CARDINAL SIN TRUST FUND FOR BUSINESS DISCIPLESHIP.......................23-24 CLUSTER/COMMITTEE REPORTS Formation of BBC Chapters..........................................................................13 Mary Belle S. Beluan Cluster on Labor & Employment................................................................23-24 Executive Director/Editor Committee on Social Justice & Agrarian Reform.....................................31-37 Coalition Against Corruption -BBC -LAIKO Government Procurement Monitoring Project.......................................................................................38-45 Replication of Government Procurement Monitoring............................46-52 -

DIRECTORY of PDIC MEMBER RURAL BANKS As of 27 July 2021

DIRECTORY OF PDIC MEMBER RURAL BANKS As of 27 July 2021 NAME OF BANK BANK ADDRESS CONTACT NUMBER * 1 Advance Credit Bank (A Rural Bank) Corp. (Formerly Advantage Bank Corp. - A MFO RB) Stop Over Commercial Center, Gerona-Pura Rd. cor. MacArthur Highway, Brgy. Abagon, Gerona, Tarlac (045) 931-3751 2 Agribusiness Rural Bank, Inc. 2/F Ropali Plaza Bldg., Escriva Dr. cor. Gold Loop, Ortigas Center, Brgy. San Antonio, City of Pasig (02) 8942-2474 3 Agricultural Bank of the Philippines, Inc. 121 Don P. Campos Ave., Brgy. Zone IV (Pob.), City of Dasmariñas, Cavite (046) 416-3988 4 Aliaga Farmers Rural Bank, Inc. Gen. Luna St., Brgy. Poblacion West III, Aliaga, Nueva Ecija (044) 958-5020 / (044) 958-5021 5 Anilao Bank (Rural Bank of Anilao (Iloilo), Inc. T. Magbanua St., Brgy. Primitivo Ledesma Ward (Pob.), Pototan, Iloilo (033) 321-0159 / (033) 362-0444 / (033) 393-2240 6 ARDCIBank, Inc. - A Rural Bank G/F ARDCI Corporate Bldg., Brgy. San Roque (Pob.), Virac, Catanduanes (0908) 820-1790 7 Asenso Rural Bank of Bautista, Inc. National Rd., Brgy. Poblacion East, Bautista, Pangasinan (0917) 817-1822 8 Aspac Rural Bank, Inc. ASPAC Bank Bldg., M.C. Briones St. (Central Nautical Highway) cor. Gen. Ricarte St., Brgy. Guizo, City of Mandaue, Cebu (032) 345-0930 9 Aurora Bank (A Microfinance-Oriented Rural Bank), Inc. GMA Farms Building, Rizal St., Brgy. V (Pob.), Baler, Aurora (042) 724-0095 10 Baclaran Rural Bank, Inc. 83 Redemptorist Rd., Brgy. Baclaran, City of Parañaque (02) 8854-9551 11 Balanga Rural Bank, Inc. Don Manuel Banzon Ave., Brgy. -

Summary of Barangays Susceptible to Taal

Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY PHILIPPINE INSTITUTE OF VOLCANOLOGY AND SEISMOLOGY SUMMARY OF BARANGAYS SUSCEPTIBLE TO TAAL VOLCANO BASE SURGE PROVINCE MUNICIPALITY BARANGAY BATANGAS AGONCILLO Adia BATANGAS AGONCILLO Bagong Sikat BATANGAS AGONCILLO Balangon BATANGAS AGONCILLO Bilibinwang BATANGAS AGONCILLO Bangin BATANGAS AGONCILLO Barigon BATANGAS AGONCILLO Coral Na Munti BATANGAS AGONCILLO Guitna BATANGAS AGONCILLO Mabini BATANGAS AGONCILLO Pamiga BATANGAS AGONCILLO Panhulan BATANGAS AGONCILLO Pansipit BATANGAS AGONCILLO Poblacion BATANGAS AGONCILLO Pook BATANGAS AGONCILLO San Jacinto BATANGAS AGONCILLO San Teodoro BATANGAS AGONCILLO Santa Cruz BATANGAS AGONCILLO Santo Tomas BATANGAS AGONCILLO Subic Ibaba BATANGAS AGONCILLO Subic Ilaya BATANGAS AGONCILLO Banyaga BATANGAS ALITAGTAG Ping-As BATANGAS ALITAGTAG Poblacion East BATANGAS ALITAGTAG Poblacion West BATANGAS ALITAGTAG Santa Cruz BATANGAS ALITAGTAG Tadlac BATANGAS BALETE Calawit BATANGAS BALETE Looc BATANGAS BALETE Magapi BATANGAS BALETE Makina BATANGAS BALETE Malabanan BATANGAS BALETE Palsara BATANGAS BALETE Poblacion BATANGAS BALETE Sala BATANGAS BALETE Sampalocan BATANGAS BALETE Solis BATANGAS BALETE San Sebastian BATANGAS CUENCA Calumayin BATANGAS CUENCA Don Juan 1 BATANGAS CUENCA San Felipe BATANGAS LAUREL As-Is BATANGAS LAUREL Balakilong BATANGAS LAUREL Berinayan BATANGAS LAUREL Bugaan East BATANGAS LAUREL Bugaan West BATANGAS LAUREL Buso-buso BATANGAS LAUREL Gulod BATANGAS LAUREL J. Leviste BATANGAS LAUREL Molinete BATANGAS LAUREL Paliparan -

2016 Calabarzon Regional Development Report

2016 CALABARZON Regional Development Report Regional Development Council IV-A i 2016 CALABARZON REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT REPORT Foreword HON. HERMILANDO I. MANDANAS RDC Chairperson The 2016 Regional Development Report is an annual assessment of the socio- economic performance of the Region based on the targets of the Regional Development Plan 2011-2016. It highlights the performance of the key sectors namely macroeconomy, industry and services, agriculture and fisheries, infrastructure, financial, social, peace and security, governance and environment. It also includes challenges and prospects of each sector. The RDC Secretariat, the National Economic and Development Authority Region IV-A, led the preparation of the 2016 RDR by coordinating with the regional line agencies (RLAs), local government units (LGUs), state colleges and universities (SUCs) and civil society organizations (CSOs). The RDR was reviewed and endorsed by the RDC sectoral committees. The results of assessment and challenges and prospects in each sector will guide the planning and policy direction, and programming of projects in the region. The RLAs, LGUs, SUCs and development partners are encouraged to consider the RDR in their development planning initiatives for 2017-2022. 2016 Regional Development Report i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. Foreword i Table of Contents ii List of Tables iii List of Figures vii List of Acronyms ix Executive Summary xiii Chapter I: Pursuit of Inclusive Growth 1 Chapter II: Macroeconomy 5 Chapter III: Competitive Industry and Services Sector 11 Chapter IV: Competitive and Sustainable Agriculture and Fisheries Sector 23 Chapter V: Accelerating Infrastructure Development 33 Chapter VI: Towards a Resilient and Inclusive Financial System 43 Chapter VII: Good Governance and Rule of Law 53 Chapter VIII: Social Development 57 Chapter IX: Peace and Security 73 Chapter X: Conservation, Protection and Rehabilitation of the Environment and 79 Natural Resources Credit 90 2016 Regional Development Report ii LIST OF TABLES No. -

Hamon Ni Arsobispo Arguelles Ful Witness to Their Adherence to Christ.” #UB Seryosong Ipinaalala Ng Lubhang Kgg

JUNE“TRANSFORMATIO 2010 et CONSECRATIO”... JUBILEE YEAR ( APRIL 2010 - APRIL 2011)1 PAPAL INTENTION FOR JUNE 2010 Respect Life VATICAN CITY - Benedict XVI will be praying in June that national and international insti- tutions will respect life. The Apostleship of Prayer announced the intentions cho- YEAR VI NO. 6 OFFICIAL NEWSPAPER OF THE ARCHDIOCESE OF LIPA JUNE 2010 sen by the Pope for June. His general prayer intention Sa Kapistahan ng Kamahal-mahalang Puso... is: “That every national and trans-national institution may strive to guarantee respect for human life from conception to “Debosyon dapat maipakita sa natural death.” The Holy Father also chooses an apostolic intention for each month. In June he will pray: “That the Churches in Asia, pagmamahal at pagmamalasakit sa which constitute a ‘little flock’ among non-Christian popula- tions, may know how to commu- nicate the Gospel and give joy- kapwa,” hamon ni Arsobispo Arguelles ful witness to their adherence to Christ.” #UB Seryosong ipinaalala ng Lubhang Kgg. Arsobispo Ramon C. Arguelles sa kanyang mga taga-pakinig, kabilang ang mga nakikinig sa DWAL-FM 95.9 Radyo Totoo, na ang debosyon sa Kamahal-mahalang Puso ni Hesus ay hindi lamang sa paraan ng pagsasagawa ng mga panalangin at pagpaparangal tulad ng prusisyon at banal na oras. “Hindi dapat matapos ang mga ginawang pagno- nobena at Misa ang ating pagde-debosyon kay Hesus, kundi ang dapat ay ipakita ang Mabathalang Awa na siyang sinasagisag ng puso ni Photo by: FR. ERIC A. Hesus sa pamamagitan ng FOR INQUIRIES CONTACT: Pinangunahan ni Arsobispo Arguelles ang Misa sa pagtatapos ng Taon ng “Twin Hearts” kung ating mga pakikilahok sa 756-2175, 756-4190, 756-1547 saan sinariwa ng mga madre at mga pari ang kanilang mga sumpa at pagtatalaga sa Panginoon. -

International Marian Association Letter to Cardinal Mueller

International Marian Association Letter to Cardinal Mueller 31 May 2017 Eminence, Gerhard Cardinal Müller Prefect, Congregation for the Doctrine on Faith Piazza del S. Uffizio, 11 00193 Roma, Italy Your Eminence: We, Executive Members of the International Marian Association, which consti- tutes over 100 theologians, cardinals, bishops, clergy, religious and lay leaders from 5 continents, wish to, first of all, thank you for the many excellent and courageous articulations and defenses of our holy Catholic Faith, as contained in your recently released, The Cardinal Müller Report. At the same time, we are obliged to express to you our grave concern regarding your comment from the text when you state: “(for example, the Church … does not call her [Mary] “co-redeemer,” because the only Redeemer is Christ, and she herself has been redeemed sublimiore modo, as Lumen Gentium [n. 53] says, and serves this redemption wrought exclusively by Christ… (p. 133). You unfortunately refer to this term as an example of false exaggeration: “falsely exaggerating per excessum, attributing to the Virgin what is not attributable to her” (Ibid.). Your Eminence, in making this statement, albeit as a private theologian since a public interview carries no authoritative or magisterial status, you have publicly stated: 1) a theologically and historically erroneous position, since the Church undeni- ably has and does call Mary a co-redeemer; and 2) a position which, in itself, materially dissents from the repeated and authoritative teachings of the Papal Magisterium, the historical teachings from your own Congregation for the Doctrine of Faith (Holy Office)and other Vatican Congregations; the pre- and post-conciliar teachings of the Magisterium as expressed through numerous cardinals, bishops and national episcopal conferences; teachings of the broader Church, inclusive of multiple can- onized saints and blessed who all do, in fact, assent to and theologically expand upon the authentic Magisterial teachings of the Church concerning Mary as a co- redeemer. -

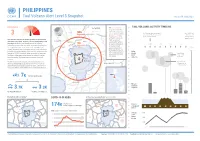

PHILIPPINES Taal Volcano Alert Level 3 Snapshot As of 09 July 2021

PHILIPPINES Taal Volcano Alert Level 3 Snapshot As of 09 July 2021 Maragondon Cabuyao City TAALVictoria VOLCANIC ACTIVITY TIMELINE Alert level Silang LAGUNA With Alert Level 3 on, Indang danger zone in the 7-km City of Calamba Amadeo radius of Taal volcano has Mendez 14km been declared. Should the On 1 July, alert level was raised to 3 As of July 9, Taal danger zone Los Baños after a short-lived phreatomagmatic Volcano is still 3 Bay Alert increase to 4, this plume, 1 km-high occured showing signs of Magallanes will likely be extended to Calauan magmatic unrest Taal Volcano continues to spew high levels of sulfur dioxide 14-km as with 2020 Alfonso Talisay Santo and steam rich plumes, including volcanic earthquakes, in the CAVITE Tagaytay City Tomaseruption, which will drive Nasugbu past days. While alert level 3 remains over the volcano, 7km the number of displaced. 1 JULY 3 JULY 5 JULY 7 JULY volcanologists warn that an eruption is imminent but may not danger zone At the peak of 2020 HEIGHT be as explosive as the 2020 event. Local authorities have City of Tanauan eruption some 290,000 (IN METERS) started identifying more evacuation sites to ensure adherence people were displaced in 3K to health and safety protocols. Plans are also underway for the Laurel 500 evacuation centers or Sulfur transfer of COVID-19 patients under quarantine to temporary Alaminos dioxide Lowest since were staying with friends San Pablo City facilities in other areas, while vaccination sites will also be Malvar (SO2) 1 July at 5.3K Tuy and relatives. -

Mga Milagro Ng Birheng Maria (Miracles of the Virgin Mary): Symbolism and Expression of Marian Devotion in the Philippines

Mga Milagro ng Birheng Maria (Miracles of the Virgin Mary): Symbolism and Expression of Marian devotion in the Philippines Mark Iñigo M. Tallara, Ph.D. Candidate National University of Singapore SUMMARY This paper is about Catholicism in the Philippines, highlighting the events, and objects on the popular devotion to the Birheng Maria (Virgin Mary), that could give fresh look onto the process of formulating an alternative discourse on religious piety and identity formation. This study also calls for more scholarly attention on the historical and religious connection between Spain, Mexico, and the Philippines, focusing on the legacies of the Manila Galleon that through them we can better appreciate the Latin American dimension of Filipino Catholicism. In addition to the goods, the Manila Galleon facilitated the first transpacific people to people exchange and their ideas, customs, and most importantly the aspects of religious life. This study will examine the symbolism and expression of Filipinos’ devotion to the miraculous image of Nuestra Señora de la Paz y Buen Viaje (Our Lady of Peace and Good Voyage) or popularly known as the Black Virgin Mary of Antipolo1. What are the motivations of the devotees to the Black Virgin? How has the popular devotion to the Virgin Mary changed overtime? Observing a particular group of devotees and their practices could provide materials for the study of pilgrimage and procession. Then apply those features and analysis in order to formulate a method that is suitable for the study of popular piety in the Philippines. Although the origin of the devotion to the Black Virgin Mary of Antipolo is central to my arguments, the study will also take a broader consideration of the origins of Marianism in the Philippines. -

Summary of Barangays Susceptible To

Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY PHILIPPINE INSTITUTE OF VOLCANOLOGY AND SEISMOLOGY SUMMARY OF BARANGAYS SUSCEPTIBLE TO TAAL VOLCANO TSUNAMI (as of 16 January 2020) PROVINCE MUNICIPALITY BARANGAY BATANGAS AGONCILLO Adia BATANGAS AGONCILLO Bagong Sikat BATANGAS AGONCILLO Bilibinwang BATANGAS AGONCILLO Bangin BATANGAS AGONCILLO Guitna BATANGAS AGONCILLO Panhulan BATANGAS AGONCILLO Pansipit BATANGAS AGONCILLO Pook BATANGAS AGONCILLO San Teodoro BATANGAS AGONCILLO Santa Cruz BATANGAS AGONCILLO Santo Tomas BATANGAS AGONCILLO Subic Ibaba BATANGAS AGONCILLO Subic Ilaya BATANGAS AGONCILLO Banyaga BATANGAS ALITAGTAG Ping-As BATANGAS ALITAGTAG Poblacion East BATANGAS ALITAGTAG Poblacion West BATANGAS ALITAGTAG Santa Cruz BATANGAS ALITAGTAG Tadlac BATANGAS BALETE Calawit BATANGAS BALETE Looc BATANGAS BALETE Magapi BATANGAS BALETE Makina BATANGAS BALETE Malabanan BATANGAS BALETE Palsara BATANGAS BALETE Poblacion BATANGAS BALETE Sala BATANGAS BALETE Sampalocan BATANGAS BALETE Solis BATANGAS BALETE San Sebastian BATANGAS CUENCA Calumayin BATANGAS CUENCA Don Juan BATANGAS CUENCA San Felipe BATANGAS LAUREL As-Is BATANGAS LAUREL Balakilong BATANGAS LAUREL Berinayan BATANGAS LAUREL Bugaan East BATANGAS LAUREL Bugaan West 1 BATANGAS LAUREL Buso-buso BATANGAS LAUREL Gulod BATANGAS LAUREL J. Leviste BATANGAS LAUREL Molinete BATANGAS LAUREL Paliparan BATANGAS LAUREL Barangay 1 (Pob.) BATANGAS LAUREL Barangay 2 (Pob.) BATANGAS LAUREL Barangay 3 (Pob.) BATANGAS LAUREL Barangay 4 (Pob.) BATANGAS LAUREL Barangay 5 (Pob.) BATANGAS -

Bishop Midyphil Bermejo “Dodong” Billones by Bro

GREETINGS FROM. BOY & AGNES YAMBAO AND FAMILY 35TH BIENNIAL NATIONAL CONVENTION CFM BECOMING GOOD NEWS AT HOME AND TO THE WORLD OUR MISSION Our mission is to be evangelized and to evangelized families and communities through our family and life programs and advocacies. OUR VISION We are a community of evangelized families witnessing to Christ, sanctified by the Spirit in building the Father’s kingdom. OUR CORE VALUES Evangelization Stewardship Servanthood Family Spirituality Pro-life CFM 3 PAGE 35TH BIENNIAL NATIONAL CONVENTION CFM BECOMING GOOD NEWS AT HOME AND TO THE WORLD CFM Logo The symbol for the Christian Family Movement is made up of four component parts: the ancient sign for man, woman and child with the Christian symbol for Christ, joined in beautiful harmony to form a single unit, indicating the most basic characteristics of the Christian family. Christ - Superimposed upon the whole is the symbol; for Christ, the Chi Rho, who holds the center place in the family unit. Man - Shown with arms lifted up to Gods, standing as a tower of great strength, exemplifying his place as head of the family. Woman - Reaching toward the earth, beautifully demonstrating her likeness to the earth in her fertility - the place she holds in the divine plan of creation fulfilled in the family unit. Child - The circle, as a sign of life, represents the child, showing the closeness of the power of man and woman to God’s power of creation. CFM 114 PAGE 35TH BIENNIAL NATIONAL CONVENTION CFM BECOMING GOOD NEWS AT HOME AND TO THE WORLD CATHOLIC BISHOP’S -

Reg-04-Wo-10.Pdf

Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF LABOR AND EMPLOYMENT National Wages and Productivity Commission Regional Tripartite Wages and Productivity Board No. IV-A City of Calamba, Laguna WAGE ORDER NO. IVA-10 SETTING THE MINIMUM WAGE FOR CALABARZON AREA WHEREAS, under R. A. 6727, Regional Tripartite Wages and Productivity Board -IVA (RTWPB- IVA) is mandated to rationalize minimum wage fixing in the Region considering the prevailing socio- economic condition affecting the cost of living of wage earners, the generation of new jobs and preservation of existing employment, the capacity to pay and sustainable viability and competitiveness of business and industry, and the interest of both labor and management; WHEREAS, the Board issued Wage Order No. IVA-09, as amended granting wage increases to all covered private sector workers in the Region effective 01 November 2004; WHEREAS, the Board in anticipation of the wage issue convened on 13 April 2005 to discuss and formulate action plan/s to resolve the issue; WHEREAS, the Board guided by the instruction of President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo on Labor Day (May 1, 2005) for the Regional Boards to resolve the wage issue within thirty (30) days initiated assessment of the socio-economic situation of the Region and conducted sectoral consultations and public hearing on the wage issue; WHEREAS, the Board conducted series of wage consultations with employers sector locating in industrial parks/economic zones in the Provinces/Municipalities of Sto. Tomas, Batangas on 26 April 2005, Dasmariñas, Cavite on 18 May 2005, Biñan, Laguna on 19 and 24 May 2005, and Canlubang, Laguna on 23 May 2005. -

Story Endings

Thursday, January 29, 2009 FROM THE ARCHIVES Southern Cross, Page 3 Story endings: A young woman’s vocation; an architect’s death; and the return of two priests from the Philippines to their homeland he lovely face of Peggy Dee Reid looks up from a page in a 1946 ing room. There, he located Mrs. in the diocese was shorter. After Tissue of The Bulletin of the Catholic Laymen’s Association. The Foley and her daughter, Mattie. serving temporarily at Saint daughter of the former editor of the paper, she is entering the novitiate After leading the women to Teresa Catholic Church in Albany, of the Ursuline Order in Beacon, New York. Earlier, she had graduated safety, Engineer Barry attempted he went on to complete his post- from the College of New Rochelle conducted by the Ursuline Order, win- to enter Daniel Foley’s room, but graduate studies at Catholic Uni- ning honors along the way. Whatever became of Peggy Dee Reid? Did was forced back by flames. When versity in Washington, D.C. Both her vocation hold true? the fire was put out, authorities Father Olalia and Father Pengson determined that Foley had died in spent the war years worrying A 2008 Southern Cross article many years of service to the his bed and that the possible cause about the welfare of their families (May 22, 2008) about Georgia’s Catholic Church in Georgia came of the fire was the explosion of a in the Japanese-occupied Phi- Catholic architects references to a close with his appointment as lamp in the architect’s room.