What's So Baffling About Negative Numbers?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Orthogonal Planes Split of Quaternions and Its Relation to Quaternion Geometry of Rotations

Home Search Collections Journals About Contact us My IOPscience The orthogonal planes split of quaternions and its relation to quaternion geometry of rotations This content has been downloaded from IOPscience. Please scroll down to see the full text. 2015 J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 597 012042 (http://iopscience.iop.org/1742-6596/597/1/012042) View the table of contents for this issue, or go to the journal homepage for more Download details: IP Address: 131.169.4.70 This content was downloaded on 17/02/2016 at 22:46 Please note that terms and conditions apply. 30th International Colloquium on Group Theoretical Methods in Physics (Group30) IOP Publishing Journal of Physics: Conference Series 597 (2015) 012042 doi:10.1088/1742-6596/597/1/012042 The orthogonal planes split of quaternions and its relation to quaternion geometry of rotations1 Eckhard Hitzer Osawa 3-10-2, Mitaka 181-8585, International Christian University, Japan E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Recently the general orthogonal planes split with respect to any two pure unit 2 2 quaternions f; g 2 H, f = g = −1, including the case f = g, has proved extremely useful for the construction and geometric interpretation of general classes of double-kernel quaternion Fourier transformations (QFT) [7]. Applications include color image processing, where the orthogonal planes split with f = g = the grayline, naturally splits a pure quaternionic three-dimensional color signal into luminance and chrominance components. Yet it is found independently in the quaternion geometry of rotations [3], that the pure quaternion units f; g and the analysis planes, which they define, play a key role in the geometry of rotations, and the geometrical interpretation of integrals related to the spherical Radon transform of probability density functions of unit quaternions, as relevant for texture analysis in crystallography. -

Euler's Square Root Laws for Negative Numbers

Ursinus College Digital Commons @ Ursinus College Transforming Instruction in Undergraduate Complex Numbers Mathematics via Primary Historical Sources (TRIUMPHS) Winter 2020 Euler's Square Root Laws for Negative Numbers Dave Ruch Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/triumphs_complex Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Educational Methods Commons, Higher Education Commons, and the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Euler’sSquare Root Laws for Negative Numbers David Ruch December 17, 2019 1 Introduction We learn in elementary algebra that the square root product law pa pb = pab (1) · is valid for any positive real numbers a, b. For example, p2 p3 = p6. An important question · for the study of complex variables is this: will this product law be valid when a and b are complex numbers? The great Leonard Euler discussed some aspects of this question in his 1770 book Elements of Algebra, which was written as a textbook [Euler, 1770]. However, some of his statements drew criticism [Martinez, 2007], as we shall see in the next section. 2 Euler’sIntroduction to Imaginary Numbers In the following passage with excerpts from Sections 139—148of Chapter XIII, entitled Of Impossible or Imaginary Quantities, Euler meant the quantity a to be a positive number. 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111 The squares of numbers, negative as well as positive, are always positive. ...To extract the root of a negative number, a great diffi culty arises; since there is no assignable number, the square of which would be a negative quantity. Suppose, for example, that we wished to extract the root of 4; we here require such as number as, when multiplied by itself, would produce 4; now, this number is neither +2 nor 2, because the square both of 2 and of 2 is +4, and not 4. -

A MATHEMATICIAN's SURVIVAL GUIDE 1. an Algebra Teacher I

A MATHEMATICIAN’S SURVIVAL GUIDE PETER G. CASAZZA 1. An Algebra Teacher I could Understand Emmy award-winning journalist and bestselling author Cokie Roberts once said: As long as algebra is taught in school, there will be prayer in school. 1.1. An Object of Pride. Mathematician’s relationship with the general public most closely resembles “bipolar” disorder - at the same time they admire us and hate us. Almost everyone has had at least one bad experience with mathematics during some part of their education. Get into any taxi and tell the driver you are a mathematician and the response is predictable. First, there is silence while the driver relives his greatest nightmare - taking algebra. Next, you will hear the immortal words: “I was never any good at mathematics.” My response is: “I was never any good at being a taxi driver so I went into mathematics.” You can learn a lot from taxi drivers if you just don’t tell them you are a mathematician. Why get started on the wrong foot? The mathematician David Mumford put it: “I am accustomed, as a professional mathematician, to living in a sort of vacuum, surrounded by people who declare with an odd sort of pride that they are mathematically illiterate.” 1.2. A Balancing Act. The other most common response we get from the public is: “I can’t even balance my checkbook.” This reflects the fact that the public thinks that mathematics is basically just adding numbers. They have no idea what we really do. Because of the textbooks they studied, they think that all needed mathematics has already been discovered. -

Is Liscussed and a Class of Spaces in Yhich the Potian of Dittance Is Defin Time Sd-Called Metric Spaces, Is Introduced

DOCUMENT RESEW Sit 030 465 - ED in ) AUTH3R Shreider, Yu A. TITLE What Is Distance? Populatt Lectu'res in Mathematios. INSTITUTI3N :".hicago Univ., Ill: Dept. of Mathematics. SPONS A3ENCY National Science Foundation, Washington, D.C. P.11B DATE 74 GRANT NSF-G-834 7 (M Al NOTE Blip.; For.relateE documents,see SE- 030 460-464: Not availabie in hard copy due :to copyright restrActi. cals. Translated and adapted from the° Russian edition. AVAILABLE FROM!he gniversity ofwChicago Press, Chicago, IL 60637 (Order No. 754987; $4.501. EDRS- PRICL: MF0-1,Plus-Postage. PC Not Available from ELMS. DESCRIPTORS College Mathemitties; Geometric Concepts; ,Higker Education; Lecture Method; Mathematics; Mathematics Curriculum; *Mathematics Education; *tlatheatatic ,Instruction; *Measurment; Secondary Education; *Secondary echool Mathematics IDENKFIERp *Distance (Mathematics); *Metric Spaces ABSTRACT Rresened is at elaboration of a course given at Moscow University for-pupils in nifith and tenthgrades/eTh development through ibstraction of the'general definiton of,distance is liscussed and a class of spaces in yhich the potian of dittance is defin time sd-called metric spaces, is introduced. The gener.al ..oon,ce V of diztance is related to a large number of mathematical phenomena. (Author/MO 14. R producttions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ************************t**************:********.********************** , . THIStiocuMENT HAS BEEN REgoltb., OOCEO EXACTve AVECCEIVEO fROM- THE 'PERSON OR.OROANIZATIONC41OIN- AIR** IT PONTS Of Vie*41010114IONS4- ! STATED 00 NOT NECESSAACT REPRE SEATOFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTIEOF IMOUCATIOH P9SITION OR POLKY ;.- r ilk 4 #. .f.) ;4',C; . fr; AL"' ' . , ... , , AV Popular Lectures in Matheniatics Survey of Recent East European Mathernatical- Literature A project conducted by Izaak Wirszup, . -

2012-13 Annual Report of Private Giving

MAKING THE EXTRAORDINARY POSSIBLE 2012–13 ANNUAL REPORT OF PRIVATE GIVING 2 0 1 2–13 ANNUAL REPORT OF PRIVATE GIVING “Whether you’ve been a donor to UMaine for years or CONTENTS have just made your first gift, I thank you for your Letter from President Paul Ferguson 2 Fundraising Partners 4 thoughtfulness and invite you to join us in a journey Letter from Jeffery Mills and Eric Rolfson 4 that promises ‘Blue Skies ahead.’ ” President Paul W. Ferguson M A K I N G T H E Campaign Maine at a Glance 6 EXTRAORDINARY 2013 Endowments/Holdings 8 Ways of Giving 38 POSSIBLE Giving Societies 40 2013 Donors 42 BLUE SKIES AHEAD SINCE GRACE, JENNY AND I a common theme: making life better student access, it is donors like you arrived at UMaine just over two years for others — specifically for our who hold the real keys to the ago, we have truly enjoyed our students and the state we serve. While University of Maine’s future level interactions with many alumni and I’ve enjoyed many high points in my of excellence. friends who genuinely care about this personal and professional life, nothing remarkable university. Events like the surpasses the sense of reward and Unrestricted gifts that provide us the Stillwater Society dinner and the accomplishment that accompanies maximum flexibility to move forward Charles F. Allen Legacy Society assisting others to fulfill their are one of these keys. We also are luncheon have allowed us to meet and potential. counting on benefactors to champion thank hundreds of donors. -

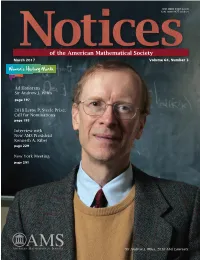

Sir Andrew J. Wiles

ISSN 0002-9920 (print) ISSN 1088-9477 (online) of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 Volume 64, Number 3 Women's History Month Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Wiles page 197 2018 Leroy P. Steele Prize: Call for Nominations page 195 Interview with New AMS President Kenneth A. Ribet page 229 New York Meeting page 291 Sir Andrew J. Wiles, 2016 Abel Laureate. “The definition of a good mathematical problem is the mathematics it generates rather Notices than the problem itself.” of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 FEATURES 197 239229 26239 Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Interview with New The Graduate Student Wiles AMS President Kenneth Section Interview with Abel Laureate Sir A. Ribet Interview with Ryan Haskett Andrew J. Wiles by Martin Raussen and by Alexander Diaz-Lopez Allyn Jackson Christian Skau WHAT IS...an Elliptic Curve? Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof by by Harris B. Daniels and Álvaro Henri Darmon Lozano-Robledo The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles by Christopher Skinner In this issue we honor Sir Andrew J. Wiles, prover of Fermat's Last Theorem, recipient of the 2016 Abel Prize, and star of the NOVA video The Proof. We've got the official interview, reprinted from the newsletter of our friends in the European Mathematical Society; "Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof" by Henri Darmon; and a collection of articles on "The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles" assembled by guest editor Christopher Skinner. We welcome the new AMS president, Ken Ribet (another star of The Proof). Marcelo Viana, Director of IMPA in Rio, describes "Math in Brazil" on the eve of the upcoming IMO and ICM. -

PRESENTAZIONE E LAUDATIO DI DAVID MUMFOD by ALBERTO

PRESENTAZIONE E LAUDATIO DI DAVID MUMFOD by ALBERTO CONTE David Mumford was born in 1937 in Worth (West Sussex, UK) in an old English farm house. His father, William Mumford, was British, ... a visionary with an international perspective, who started an experimental school in Tanzania based on the idea of appropriate technology... Mumford's father worked for the United Nations from its foundations in 1945 and this was his job while Mumford was growing up. Mumford's mother was American and the family lived on Long Island Sound in the United States, a semi-enclosed arm of the North Atlantic Ocean with the New York- Connecticut shore on the north and Long Island to the south. After attending Exeter School, Mumford entered Harvard University. After graduating from Harvard, Mumford was appointed to the staff there. He was appointed professor of mathematics in 1967 and, ten years later, he became Higgins Professor. He was chairman of the Mathematics Department at Harvard from 1981 to 1984 and MacArthur Fellow from 1987 to 1992. In 1996 Mumford moved to the Division of Applied Mathematics of Brown University where he is now Professor Emeritus. Mumford has received many honours for his scientific work. First of all, the Fields Medal (1974), the highest distinction for a mathematician. He was awarded the Shaw Prize in 2006, the Steele Prize for Mathematical Exposition by the American Mathematical Society in 2007, and the Wolf Prize in 2008. Upon receiving this award from the hands of Israeli President Shimon Peres he announced that he will donate the money to Bir Zeit University, near Ramallah, and to Gisha, an Israeli organization that advocates for Palestinian freedom of movement, by saying: I decided to donate my share of the Wolf Prize to enable the academic community in occupied Palestine to survive and thrive. -

From Counting to Quaternions -- the Agonies and Ecstasies of the Student Repeat Those of D'alembert and Hamilton

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Keck Graduate Institute Journal of Humanistic Mathematics Volume 1 | Issue 1 January 2011 From Counting to Quaternions -- The Agonies and Ecstasies of the Student Repeat Those of D'Alembert and Hamilton Reuben Hersh University of New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm Recommended Citation Hersh, R. "From Counting to Quaternions -- The Agonies and Ecstasies of the Student Repeat Those of D'Alembert and Hamilton," Journal of Humanistic Mathematics, Volume 1 Issue 1 (January 2011), pages 65-93. DOI: 10.5642/jhummath.201101.06 . Available at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/vol1/ iss1/6 ©2011 by the authors. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License. JHM is an open access bi-annual journal sponsored by the Claremont Center for the Mathematical Sciences and published by the Claremont Colleges Library | ISSN 2159-8118 | http://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/ The editorial staff of JHM works hard to make sure the scholarship disseminated in JHM is accurate and upholds professional ethical guidelines. However the views and opinions expressed in each published manuscript belong exclusively to the individual contributor(s). The publisher and the editors do not endorse or accept responsibility for them. See https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/policies.html for more information. From Counting to Quaternions { The Agonies and Ecstasies of the Student Repeat Those of D'Alembert and Hamilton Reuben Hersh Department of Mathematics and Statistics, The University of New Mexico [email protected] Synopsis Young learners of mathematics share a common experience with the greatest creators of mathematics: \hitting a wall," meaning, first frustration, then strug- gle, and finally, enlightenment and elation. -

The Evolution of Numbers

The Evolution of Numbers Counting Numbers Counting Numbers: {1, 2, 3, …} We use numbers to count: 1, 2, 3, 4, etc You can have "3 friends" A field can have "6 cows" Whole Numbers Whole numbers are the counting numbers plus zero. Whole Numbers: {0, 1, 2, 3, …} Negative Numbers We can count forward: 1, 2, 3, 4, ...... but what if we count backward: 3, 2, 1, 0, ... what happens next? The answer is: negative numbers: {…, -3, -2, -1} A negative number is any number less than zero. Integers If we include the negative numbers with the whole numbers, we have a new set of numbers that are called integers: {…, -3, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, …} The Integers include zero, the counting numbers, and the negative counting numbers, to make a list of numbers that stretch in either direction indefinitely. Rational Numbers A rational number is a number that can be written as a simple fraction (i.e. as a ratio). 2.5 is rational, because it can be written as the ratio 5/2 7 is rational, because it can be written as the ratio 7/1 0.333... (3 repeating) is also rational, because it can be written as the ratio 1/3 More formally we say: A rational number is a number that can be written in the form p/q where p and q are integers and q is not equal to zero. Example: If p is 3 and q is 2, then: p/q = 3/2 = 1.5 is a rational number Rational Numbers include: all integers all fractions Irrational Numbers An irrational number is a number that cannot be written as a simple fraction. -

Density of Algebraic Points on Noetherian Varieties 3

DENSITY OF ALGEBRAIC POINTS ON NOETHERIAN VARIETIES GAL BINYAMINI Abstract. Let Ω ⊂ Rn be a relatively compact domain. A finite collection of real-valued functions on Ω is called a Noetherian chain if the partial derivatives of each function are expressible as polynomials in the functions. A Noether- ian function is a polynomial combination of elements of a Noetherian chain. We introduce Noetherian parameters (degrees, size of the coefficients) which measure the complexity of a Noetherian chain. Our main result is an explicit form of the Pila-Wilkie theorem for sets defined using Noetherian equalities and inequalities: for any ε> 0, the number of points of height H in the tran- scendental part of the set is at most C ·Hε where C can be explicitly estimated from the Noetherian parameters and ε. We show that many functions of interest in arithmetic geometry fall within the Noetherian class, including elliptic and abelian functions, modular func- tions and universal covers of compact Riemann surfaces, Jacobi theta func- tions, periods of algebraic integrals, and the uniformizing map of the Siegel modular variety Ag . We thus effectivize the (geometric side of) Pila-Zannier strategy for unlikely intersections in those instances that involve only compact domains. 1. Introduction 1.1. The (real) Noetherian class. Let ΩR ⊂ Rn be a bounded domain, and n denote by x := (x1,...,xn) a system of coordinates on R . A collection of analytic ℓ functions φ := (φ1,...,φℓ): Ω¯ R → R is called a (complex) real Noetherian chain if it satisfies an overdetermined system of algebraic partial differential equations, i =1,...,ℓ ∂φi = Pi,j (x, φ), (1) ∂xj j =1,...,n where P are polynomials. -

Download PDF of Summer 2016 Colloquy

Nonprofit Organization summer 2016 US Postage HONORING EXCELLENCE p.20 ONE DAY IN MAY p.24 PAID North Reading, MA Permit No.8 What’s the BUZZ? Bees, behavior & pollination p.12 What’s the Buzz? 12 Bees, Behavior, and Pollination ONE GRADUATE STUDENT’S INVESTIGATION INTO BUMBLEBEE BEHAVIOR The 2016 Centennial Medalists 20 HONORING FRANCIS FUKUYAMA, DAVID MUMFORD, JOHN O’MALLEY, AND CECILIA ROUSE Intellectual Assembly 22 ALUMNI DAY 2016 One Day in May 24 COMMENCEMENT 2016 summer/16 An alumni publication of Harvard University’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences 3 FROM UNIVERSITY HALL 4 NEWS & NOTES Harvard Horizons, Health Policy turns 25, new Alumni Council leadership. 8 Q&A WITH COLLEEN CAVANAUGH A path-breaking biologist provides new evolutionary insights. 10 SHELF LIFE Elephants, Manchuria, the Uyghur nation and more. 26 NOTED News from our alumni. 28 ALUMNI CONNECTIONS Dudley 25th, Life Lab launches, and recent graduates gathering. summer Cover Image: Patrick Hruby Facing Image: Commencement Begins /16 Photograph by Tony Rinaldo CONTRIBUTORS Xiao-Li Meng dean, PhD ’90 Jon Petitt director of alumni relations and publications Patrick Hruby is a Los Angeles–based Ann Hall editor freelance illustrator and designer with Visual Dialogue design an insatiable appetite for color. His work Colloquy is published three times a year by the Graduate School Alumni has appeared in The New York Times, Association (GSAA). Governed by its Alumni Council, the GSAA represents Fortune Magazine, and WIRED, among and advances the interests of alumni of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences through alumni events and publications. others. -

Generalized Quaternion and Rotation in 3-Space E M. Jafari, Y. Yayli

TWMS J. Pure Appl. Math. V.6, N.2, 2015, pp.224-232 3 GENERALIZED QUATERNIONS AND ROTATION IN 3-SPACE E®¯ MEHDI JAFARI1, YUSUF YAYLI2 Abstract. The paper explains how a unit generalized quaternion is used to represent a rotation 3 of a vector in 3-dimensional E®¯ space. We review of some algebraic properties of generalized quaternions and operations between them and then show their relation with the rotation matrix. Keywords: generalized quaternion, quasi-orthogonal matrix, rotation. AMS Subject Classi¯cation: 15A33. 1. Introduction The quaternions algebra was invented by W.R. Hamilton as an extension to the complex numbers. He was able to ¯nd connections between this new algebra and spatial rotations. The unit quaternions form a group that is isomorphic to the group SU(2) and is a double cover of SO(3), the group of 3-dimensional rotations. Under these isomorphisms the quaternion multiplication operation corresponds to the composition operation of rotations [18]. Kula and Yayl³ [13] showed that unit split quaternions in H0 determined a rotation in semi-Euclidean 4 space E2 : In [15], is demonstrated how timelike split quaternions are used to perform rotations 3 in the Minkowski 3-space E1 . Rotations in a complex 3-dimensional space are considered in [20] and applied to the treatment of the Lorentz transformation in special relativity. A brief introduction of the generalized quaternions is provided in [16]. Also, this subject have investigated in algebra [19]. Recently, we studied the generalized quaternions, and gave some of their algebraic properties [7]. It is shown that the set of all unit generalized quaternions with the group operation of quaternion multiplication is a Lie group of 3-dimension.