A MATHEMATICIAN's SURVIVAL GUIDE 1. an Algebra Teacher I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MY UNFORGETTABLE EARLY YEARS at the INSTITUTE Enstitüde Unutulmaz Erken Yıllarım

MY UNFORGETTABLE EARLY YEARS AT THE INSTITUTE Enstitüde Unutulmaz Erken Yıllarım Dinakar Ramakrishnan `And what was it like,’ I asked him, `meeting Eliot?’ `When he looked at you,’ he said, `it was like standing on a quay, watching the prow of the Queen Mary come towards you, very slowly.’ – from `Stern’ by Seamus Heaney in memory of Ted Hughes, about the time he met T.S.Eliot It was a fortunate stroke of serendipity for me to have been at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, twice during the nineteen eighties, first as a Post-doctoral member in 1982-83, and later as a Sloan Fellow in the Fall of 1986. I had the privilege of getting to know Robert Langlands at that time, and, needless to say, he has had a larger than life influence on me. It wasn’t like two ships passing in the night, but more like a rowboat feeling the waves of an oncoming ship. Langlands and I did not have many conversations, but each time we did, he would make a Zen like remark which took me a long time, at times months (or even years), to comprehend. Once or twice it even looked like he was commenting not on the question I posed, but on a tangential one; however, after much reflection, it became apparent that what he had said had an interesting bearing on what I had been wondering about, and it always provided a new take, at least to me, on the matter. Most importantly, to a beginner in the field like I was then, he was generous to a fault, always willing, whenever asked, to explain the subtle aspects of his own work. -

The "Greatest European Mathematician of the Middle Ages"

Who was Fibonacci? The "greatest European mathematician of the middle ages", his full name was Leonardo of Pisa, or Leonardo Pisano in Italian since he was born in Pisa (Italy), the city with the famous Leaning Tower, about 1175 AD. Pisa was an important commercial town in its day and had links with many Mediterranean ports. Leonardo's father, Guglielmo Bonacci, was a kind of customs officer in the North African town of Bugia now called Bougie where wax candles were exported to France. They are still called "bougies" in French, but the town is a ruin today says D E Smith (see below). So Leonardo grew up with a North African education under the Moors and later travelled extensively around the Mediterranean coast. He would have met with many merchants and learned of their systems of doing arithmetic. He soon realised the many advantages of the "Hindu-Arabic" system over all the others. D E Smith points out that another famous Italian - St Francis of Assisi (a nearby Italian town) - was also alive at the same time as Fibonacci: St Francis was born about 1182 (after Fibonacci's around 1175) and died in 1226 (before Fibonacci's death commonly assumed to be around 1250). By the way, don't confuse Leonardo of Pisa with Leonardo da Vinci! Vinci was just a few miles from Pisa on the way to Florence, but Leonardo da Vinci was born in Vinci in 1452, about 200 years after the death of Leonardo of Pisa (Fibonacci). His names Fibonacci Leonardo of Pisa is now known as Fibonacci [pronounced fib-on-arch-ee] short for filius Bonacci. -

2012-13 Annual Report of Private Giving

MAKING THE EXTRAORDINARY POSSIBLE 2012–13 ANNUAL REPORT OF PRIVATE GIVING 2 0 1 2–13 ANNUAL REPORT OF PRIVATE GIVING “Whether you’ve been a donor to UMaine for years or CONTENTS have just made your first gift, I thank you for your Letter from President Paul Ferguson 2 Fundraising Partners 4 thoughtfulness and invite you to join us in a journey Letter from Jeffery Mills and Eric Rolfson 4 that promises ‘Blue Skies ahead.’ ” President Paul W. Ferguson M A K I N G T H E Campaign Maine at a Glance 6 EXTRAORDINARY 2013 Endowments/Holdings 8 Ways of Giving 38 POSSIBLE Giving Societies 40 2013 Donors 42 BLUE SKIES AHEAD SINCE GRACE, JENNY AND I a common theme: making life better student access, it is donors like you arrived at UMaine just over two years for others — specifically for our who hold the real keys to the ago, we have truly enjoyed our students and the state we serve. While University of Maine’s future level interactions with many alumni and I’ve enjoyed many high points in my of excellence. friends who genuinely care about this personal and professional life, nothing remarkable university. Events like the surpasses the sense of reward and Unrestricted gifts that provide us the Stillwater Society dinner and the accomplishment that accompanies maximum flexibility to move forward Charles F. Allen Legacy Society assisting others to fulfill their are one of these keys. We also are luncheon have allowed us to meet and potential. counting on benefactors to champion thank hundreds of donors. -

The Astronomers Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler

Ice Core Records – From Volcanoes to Supernovas The Astronomers Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler Tycho Brahe (1546-1601, shown at left) was a nobleman from Denmark who made astronomy his life's work because he was so impressed when, as a boy, he saw an eclipse of the Sun take place at exactly the time it was predicted. Tycho's life's work in astronomy consisted of measuring the positions of the stars, planets, Moon, and Sun, every night and day possible, and carefully recording these measurements, year after year. Johannes Kepler (1571-1630, below right) came from a poor German family. He did not have it easy growing Tycho Brahe up. His father was a soldier, who was killed in a war, and his mother (who was once accused of witchcraft) did not treat him well. Kepler was taken out of school when he was a boy so that he could make money for the family by working as a waiter in an inn. As a young man Kepler studied theology and science, and discovered that he liked science better. He became an accomplished mathematician and a persistent and determined calculator. He was driven to find an explanation for order in the universe. He was convinced that the order of the planets and their movement through the sky could be explained through mathematical calculation and careful thinking. Johannes Kepler Tycho wanted to study science so that he could learn how to predict eclipses. He studied mathematics and astronomy in Germany. Then, in 1571, when he was 25, Tycho built his own observatory on an island (the King of Denmark gave him the island and some additional money just for that purpose). -

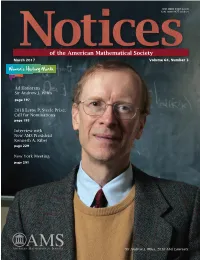

Sir Andrew J. Wiles

ISSN 0002-9920 (print) ISSN 1088-9477 (online) of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 Volume 64, Number 3 Women's History Month Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Wiles page 197 2018 Leroy P. Steele Prize: Call for Nominations page 195 Interview with New AMS President Kenneth A. Ribet page 229 New York Meeting page 291 Sir Andrew J. Wiles, 2016 Abel Laureate. “The definition of a good mathematical problem is the mathematics it generates rather Notices than the problem itself.” of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 FEATURES 197 239229 26239 Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Interview with New The Graduate Student Wiles AMS President Kenneth Section Interview with Abel Laureate Sir A. Ribet Interview with Ryan Haskett Andrew J. Wiles by Martin Raussen and by Alexander Diaz-Lopez Allyn Jackson Christian Skau WHAT IS...an Elliptic Curve? Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof by by Harris B. Daniels and Álvaro Henri Darmon Lozano-Robledo The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles by Christopher Skinner In this issue we honor Sir Andrew J. Wiles, prover of Fermat's Last Theorem, recipient of the 2016 Abel Prize, and star of the NOVA video The Proof. We've got the official interview, reprinted from the newsletter of our friends in the European Mathematical Society; "Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof" by Henri Darmon; and a collection of articles on "The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles" assembled by guest editor Christopher Skinner. We welcome the new AMS president, Ken Ribet (another star of The Proof). Marcelo Viana, Director of IMPA in Rio, describes "Math in Brazil" on the eve of the upcoming IMO and ICM. -

PRESENTAZIONE E LAUDATIO DI DAVID MUMFOD by ALBERTO

PRESENTAZIONE E LAUDATIO DI DAVID MUMFOD by ALBERTO CONTE David Mumford was born in 1937 in Worth (West Sussex, UK) in an old English farm house. His father, William Mumford, was British, ... a visionary with an international perspective, who started an experimental school in Tanzania based on the idea of appropriate technology... Mumford's father worked for the United Nations from its foundations in 1945 and this was his job while Mumford was growing up. Mumford's mother was American and the family lived on Long Island Sound in the United States, a semi-enclosed arm of the North Atlantic Ocean with the New York- Connecticut shore on the north and Long Island to the south. After attending Exeter School, Mumford entered Harvard University. After graduating from Harvard, Mumford was appointed to the staff there. He was appointed professor of mathematics in 1967 and, ten years later, he became Higgins Professor. He was chairman of the Mathematics Department at Harvard from 1981 to 1984 and MacArthur Fellow from 1987 to 1992. In 1996 Mumford moved to the Division of Applied Mathematics of Brown University where he is now Professor Emeritus. Mumford has received many honours for his scientific work. First of all, the Fields Medal (1974), the highest distinction for a mathematician. He was awarded the Shaw Prize in 2006, the Steele Prize for Mathematical Exposition by the American Mathematical Society in 2007, and the Wolf Prize in 2008. Upon receiving this award from the hands of Israeli President Shimon Peres he announced that he will donate the money to Bir Zeit University, near Ramallah, and to Gisha, an Israeli organization that advocates for Palestinian freedom of movement, by saying: I decided to donate my share of the Wolf Prize to enable the academic community in occupied Palestine to survive and thrive. -

Robert P. Langlands Receives the Abel Prize

Robert P. Langlands receives the Abel Prize The Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters has decided to award the Abel Prize for 2018 to Robert P. Langlands of the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, USA “for his visionary program connecting representation theory to number theory.” Robert P. Langlands has been awarded the Abel Prize project in modern mathematics has as wide a scope, has for his work dating back to January 1967. He was then produced so many deep results, and has so many people a 30-year-old associate professor at Princeton, working working on it. Its depth and breadth have grown and during the Christmas break. He wrote a 17-page letter the Langlands program is now frequently described as a to the great French mathematician André Weil, aged 60, grand unified theory of mathematics. outlining some of his new mathematical insights. The President of the Norwegian Academy of Science and “If you are willing to read it as pure speculation I would Letters, Ole M. Sejersted, announced the winner of the appreciate that,” he wrote. “If not – I am sure you have a 2018 Abel Prize at the Academy in Oslo today, 20 March. waste basket handy.” Biography Fortunately, the letter did not end up in a waste basket. His letter introduced a theory that created a completely Robert P. Langlands was born in New Westminster, new way of thinking about mathematics: it suggested British Columbia, in 1936. He graduated from the deep links between two areas, number theory and University of British Columbia with an undergraduate harmonic analysis, which had previously been considered degree in 1957 and an MSc in 1958, and from Yale as unrelated. -

Commodity and Energy Markets Conference at Oxford University

Commodity and Energy Markets Conference Annual Meeting 2017 th th 14 - 15 June Page | 1 Commodity and Energy Markets Conference Contents Welcome 3 Essential Information 4 Bird’s-eye view of programme 6 Detailed programme 8 Venue maps 26 Mezzanine level of Andrew Wiles Building 27 Local Information 28 List of Participants 29 Keynote Speakers 33 Academic journals: special issues 34 Sponsors 35 Page | 2 Welcome On behalf of the Mathematical Institute, it is our great pleasure to welcome you to the University of Oxford for the Commodity and Energy Markets annual conference (2017). The Commodity and Energy Markets annual conference 2017 is the latest in a long standing series of meetings. Our first workshop was held in London in 2004, and after that we expanded the scope and held yearly conferences in different locations across Europe. Nowadays, the Commodity and Energy Markets conference is the benchmark meeting for academics who work in this area. This year’s event covers a wide range of topics in commodities and energy. We highlight three keynote talks. Prof Hendrik Bessembinder (Arizona State University) will talk on “Measuring returns to those who invest in energy through futures”, and Prof Sebastian Jaimungal (University of Toronto) will talk about “Stochastic Control in Commodity & Energy Markets: Model Uncertainty, Algorithmic Trading, and Future Directions”. Moreover, Tony Cocker, E.ON’s Chief Executive Officer, will share his views and insights into the role of mathematical modelling in the energy industry. In addition to the over 100 talks, a panel of academics and professional experts will discuss “The future of energy trading in the UK and Europe: a single energy market?” The roundtable is sponsored by the Italian Association of Energy Suppliers and Traders (AIGET) and European Energy Retailers (EER). -

Newton.Indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 14:45 | Pag

omslag Newton.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 14:45 | Pag. 1 e Dutch Republic proved ‘A new light on several to be extremely receptive to major gures involved in the groundbreaking ideas of Newton Isaac Newton (–). the reception of Newton’s Dutch scholars such as Willem work.’ and the Netherlands Jacob ’s Gravesande and Petrus Prof. Bert Theunissen, Newton the Netherlands and van Musschenbroek played a Utrecht University crucial role in the adaption and How Isaac Newton was Fashioned dissemination of Newton’s work, ‘is book provides an in the Dutch Republic not only in the Netherlands important contribution to but also in the rest of Europe. EDITED BY ERIC JORINK In the course of the eighteenth the study of the European AND AD MAAS century, Newton’s ideas (in Enlightenment with new dierent guises and interpre- insights in the circulation tations) became a veritable hype in Dutch society. In Newton of knowledge.’ and the Netherlands Newton’s Prof. Frans van Lunteren, sudden success is analyzed in Leiden University great depth and put into a new perspective. Ad Maas is curator at the Museum Boerhaave, Leiden, the Netherlands. Eric Jorink is researcher at the Huygens Institute for Netherlands History (Royal Dutch Academy of Arts and Sciences). / www.lup.nl LUP Newton and the Netherlands.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 16:47 | Pag. 1 Newton and the Netherlands Newton and the Netherlands.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 16:47 | Pag. 2 Newton and the Netherlands.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 16:47 | Pag. -

Math Spans All Dimensions

March 2000 THE NEWSLETTER OF THE MATHEMATICAL ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Math Spans All Dimensions April 2000 is Math Awareness Month Interactive version of the complete poster is available at: http://mam2000.mathforum.com/ FOCUS March 2000 FOCUS is published by the Mathematical Association of America in January. February. March. April. May/June. August/September. FOCUS October. November. and December. a Editor: Fernando Gouvea. Colby College; March 2000 [email protected] Managing Editor: Carol Baxter. MAA Volume 20. Number 3 [email protected] Senior Writer: Harry Waldman. MAA In This Issue [email protected] Please address advertising inquiries to: 3 "Math Spans All Dimensions" During April Math Awareness Carol Baxter. MAA; [email protected] Month President: Thomas Banchoff. Brown University 3 Felix Browder Named Recipient of National Medal of Science First Vice-President: Barbara Osofsky. By Don Albers Second Vice-President: Frank Morgan. Secretary: Martha Siegel. Treasurer: Gerald 4 Updating the NCTM Standards J. Porter By Kenneth A. Ross Executive Director: Tina Straley 5 A Different Pencil Associate Executive Director and Direc Moving Our Focus from Teachers to Students tor of Publications and Electronic Services: Donald J. Albers By Ed Dubinsky FOCUS Editorial Board: Gerald 6 Mathematics Across the Curriculum at Dartmouth Alexanderson; Donna Beers; J. Kevin By Dorothy I. Wallace Colligan; Ed Dubinsky; Bill Hawkins; Dan Kalman; Maeve McCarthy; Peter Renz; Annie 7 ARUME is the First SIGMAA Selden; Jon Scott; Ravi Vakil. Letters to the editor should be addressed to 8 Read This! Fernando Gouvea. Colby College. Dept. of Mathematics. Waterville. ME 04901. 8 Raoul Bott and Jean-Pierre Serre Share the Wolf Prize Subscription and membership questions 10 Call For Papers should be directed to the MAA Customer Thirteenth Annual MAA Undergraduate Student Paper Sessions Service Center. -

Density of Algebraic Points on Noetherian Varieties 3

DENSITY OF ALGEBRAIC POINTS ON NOETHERIAN VARIETIES GAL BINYAMINI Abstract. Let Ω ⊂ Rn be a relatively compact domain. A finite collection of real-valued functions on Ω is called a Noetherian chain if the partial derivatives of each function are expressible as polynomials in the functions. A Noether- ian function is a polynomial combination of elements of a Noetherian chain. We introduce Noetherian parameters (degrees, size of the coefficients) which measure the complexity of a Noetherian chain. Our main result is an explicit form of the Pila-Wilkie theorem for sets defined using Noetherian equalities and inequalities: for any ε> 0, the number of points of height H in the tran- scendental part of the set is at most C ·Hε where C can be explicitly estimated from the Noetherian parameters and ε. We show that many functions of interest in arithmetic geometry fall within the Noetherian class, including elliptic and abelian functions, modular func- tions and universal covers of compact Riemann surfaces, Jacobi theta func- tions, periods of algebraic integrals, and the uniformizing map of the Siegel modular variety Ag . We thus effectivize the (geometric side of) Pila-Zannier strategy for unlikely intersections in those instances that involve only compact domains. 1. Introduction 1.1. The (real) Noetherian class. Let ΩR ⊂ Rn be a bounded domain, and n denote by x := (x1,...,xn) a system of coordinates on R . A collection of analytic ℓ functions φ := (φ1,...,φℓ): Ω¯ R → R is called a (complex) real Noetherian chain if it satisfies an overdetermined system of algebraic partial differential equations, i =1,...,ℓ ∂φi = Pi,j (x, φ), (1) ∂xj j =1,...,n where P are polynomials. -

Andrew Wiles and Fermat's Last Theorem

Andrew Wiles and Fermat's Last Theorem Ton Yeh A great figure in modern mathematics Sir Andrew Wiles is renowned throughout the world for having cracked the problem first posed by Fermat in 1637: the non-existence of positive integer solutions to an + bn = cn for n ≥ 3. Wiles' famous journey towards his proof { the surprising connection with elliptic curves, the apparent success, the discovery of an error, the despondency, and then the flash of inspiration which saved the day { is known to layman and professional mathematician alike. Therefore, the fact that Sir Andrew spent his undergraduate years at Merton College is a great honour for us. In this article we discuss simple number-theoretic ideas relating to Fermat's Last Theorem, which may be of interest to current or prospective students, or indeed to members of the public. Easier aspects of Fermat's Last Theorem It goes without saying that the non-expert will have a tough time getting to grips with Andrew Wiles' proof. What follows, therefore, is a sketch of much simpler and indeed more classical ideas related to Fermat's Last Theorem. As a regrettable consequence, things like algebraic topology, elliptic curves, modular functions and so on have to be omitted. As compensation, the student or keen amateur will gain accessible insight from this section; he will also appreciate the shortcomings of these classical approaches and be motivated to prepare himself for more advanced perspectives. Our aim is to determine what can be said about the solutions to an + bn = cn for positive integers a; b; c.