New York Metropolitan Transportation Council Final Draft Regional

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traveling and Transportation to the Garrison Institute the Garrison Institute Is Located Directly Off Route 9D in Garrison, New York, Within Putnam County

Traveling and Transportation to The Garrison Institute The Garrison Institute is located directly off Route 9D in Garrison, New York, within Putnam County. The facility is 50 miles north of New York City and approximately 30 minutes south of Poughkeepsie, NY. Major highways nearby include Interstate 84, Route 9, the Palisades Parkway and the Taconic State Parkway. We offer on-site parking for those who will arrive by car. TRAIN WALKING DIRECTIONS FROM TRAIN In addition to our shuttle service, there is a one mile walking path through the woods from the Garrison Train Garrison, NY is just over an hour north from Grand Depot to the Institute, lovely during good weather. Central Station in NYC. Take the Metro North Railroad to the Garrison Train Station via the Hudson Line. Train Coming from NYC, head away from the river to the times vary but generally arrive and depart approximately southern most exit of the parking lot. Look for the sign every hour. Our complimentary, no-reservation-required that says “Arden Point”; the path heads into the woods. shuttle service is available from the Garrison Train Station Stay straight on the path all the way to Garrison Institute. during registration check-in hours, which are typically After about 10 minutes the path gets narrower, rockier, 3 – 6pm. The Garrison Institute is approximately one mile and somewhat uphill; you will need walking shoes. away from the train station, and there is also a walking path through the woods from the station to the Institute. Eventually, you will see a sign for Garrison Institute and come to a big field. -

Chapter 5 Transportation Planning Base Studies Village of Rye Brook, New York

Chapter 5 Transportation Planning Base Studies Village of Rye Brook, New York CHAPTER 5 TRANSPORTATION This chapter provides background on transportation elements af- fecting residents, commuters and businesses in the Village of Rye Brook. These elements include the road system, public transporta- tion, and Westchester County Airport (HPN). The moving of people and goods is essential for any community. Community transporta- tion assets, traffic conditions and census data are presented here to allow the full transportation picture for the Village of Rye Brook. 5.1 Road System The road system in the Village of Rye Brook includes limited ac- cess roadways, major arterial roadways, collector roads and local streets. There are approximately 30 miles of roadways in the Vil- lage. Each roadway is designed to serve a different function to move people and goods in an efficient manner. Map 5-1 Road Net- work on page 5-2 shows the four categories of roadways. A. Limited Access Roadways Limited access roadways consist of routes that do not have many access points except at major roadway intersections, or in the case of interstates or parkways, only have access through controlled in- Figure 5-1. Tappan Zee Bridge terchanges. Some of these roadways exclude certain vehicles, such as commercial trucks and/or buses. There are two limited access roadways in the Village of Rye Brook: a. Interstate 287 - is an east-west Federal interstate route that runs through the central part of Westchester County. Interstate 287 (I- 287) connects to the Tappan Zee Bridge in Tarrytown and Interstate 95 (I-95) in Port Chester. -

Rockland County Transit Schedules on Presidents'

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE February 13, 2018 Contact: Michael Prendergast (845) 364-2085 Rockland County Transit Schedules on Presidents’ Day POMONA, NY – Rockland County Executive Ed Day and the Department of Public Transportation have announced that most Transport of Rockland (TOR) buses will operate Saturday service on Presidents’ Day – Monday, February 19 th , plus the TOR #95 will operate to serve Rockland Community College. TAPPAN ZEExpress (TZx) buses will operate Weekend service. TRIPS paratransit bus service will operate ADA service only. Go to www.rocklandbus.com for schedules and to sign up for free Transit Alerts. Monday, February 19th: TOR will operate Saturday schedules on routes 59, 91, 92, 93, 94 and Loop 3. TOR #95 WILL operate, as Rockland Community College will be open on Presidents’ Day. TOR Loops #1 and #2 will operate regular weekday schedules. TOR #97 WILL NOT operate. TZx buses will operate a Weekend schedule. TRIPS paratransit buses will operate ADA service only. Clarkstown Mini Trans buses will operate regular Weekday service. Spring Valley Jitney buses will not operate. Coach USA’s Rockland Coaches local bus routes 9, 9W, 11-A, and 20 will operate Saturday schedules. Commuter express routes 45, 47 & 49 will not operate. Go to www.coachusa.com . Saddle River Tours route 11-C will operate a Saturday schedule. Go to www.srtbus.com . Coach USA Shortline buses will operate modified Holiday service. Coach USA Express Exit 14 bus service will not operate. Go to www.coachusa.com . Monsey Trails will operate Special Holiday service. Go to www.monseybus.com . The Haverstraw-Ossining Ferry will not operate. -

Connect Mid-Hudson Regional Transit Study

CONNECT MID-HUDSON Transit Study Final Report | January 2021 1 2 CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................................. 4 2. Service Overview ...................................................................................................................................................................... 5 2.1. COVID-19 ...................................................................................................................................................................... 9 2.2. Public Survey ................................................................................................................................................................ 9 2.2.1. Dutchess County ............................................................................................................................................10 2.2.2. Orange County ................................................................................................................................................11 2.2.3. Ulster County ..................................................................................................................................................11 3. Transit Market Assessment and Gaps Analsysis ..................................................................................................................12 3.1. Population Density .....................................................................................................................................................12 -

I. Goals and Objectives Ii. Land Use Plan

I. GOALS AND OBJECTIVES GOALS ........................................................................................................................................................ I-2 OBJECTIVES .............................................................................................................................................. I-3 Land Use ................................................................................................................................................. I-3 Housing.................................................................................................................................................... I-7 Circulation ................................................................................................................................................ I-8 Economic Development ......................................................................................................................... I-10 Utilities ................................................................................................................................................... I-11 Conservation ......................................................................................................................................... I-12 Community Facilities ............................................................................................................................. I-13 Parks and Recreation ........................................................................................................................... -

Operator Profile 2002 - 2003

BUS OPERATOR PROFILE 2002 - 2003 Operator .Insp 02-03 .OOS 02-03 OOS Rate 02-03 OpID City Region 112 LIMOUSINE INC. 2 0 0.0 28900 CENTER MORICHES 10 1ST. CHOICE AMBULETTE SERVICE LCC 1 0 0.0 29994 HICKSVILLE 10 2000 ADVENTURES & TOURS INC 5 2 40.0 26685 BROOKLYN 11 217 TRANSPORTATION INC 5 1 20.0 24555 STATEN ISLAND 11 21ST AVE. TRANSPORTATION 201 30 14.9 03531 BROOKLYN 11 3RD AVENUE TRANSIT 57 4 7.0 06043 BROOKLYN 11 A & A ROYAL BUS COACH CORP. 1 1 100.0 30552 MAMARONECK 08 A & A SERVICE 17 3 17.6 05758 MT. VERNON 08 A & B VAN SERVICE 4 1 25.0 03479 STATEN ISLAND 11 A & B'S DIAL A VAN INC. 23 1 4.3 03339 ROCKAWAY BEACH 11 A & E MEDICAL TRANSPORT INC 60 16 26.7 06165 CANANDAIGUA 04 A & E MEDICAL TRANSPORT INC. 139 29 20.9 05943 POUGHKEEPSIE 08 A & E TRANSPORT 4 0 0.0 05508 WATERTOWN 03 A & E TRANSPORT SERVICES 39 1 2.6 06692 OSWEGO 03 A & E TRANSPORT SERVICES INC 154 25 16.2 24376 ROCHESTER 04 A & E TRANSPORT SERVICES INC. 191 35 18.3 02303 OSWEGO 03 A 1 AMBULETTE INC 9 0 0.0 20066 BROOKLYN 11 A 1 LUXURY TRANSPORTATION INC. 4 2 50.0 02117 BINGHAMTON 02 A CHILDCARE OF ROOSEVELT INC. 5 1 20.0 03533 ROOSEVELT 10 A CHILD'S GARDEN DAY CARE 1 0 0.0 04307 ROCHESTER 04 A CHILDS PLACE 12 7 58.3 03454 CORONA 11 A J TRANSPORTATION 2 1 50.0 04500 NEW YORK 11 A MEDICAL ESCORT AND TAXI 2 2 100.0 28844 FULTON 03 A&J TROUS INC. -

Bus Operator Profiles 2018

OPERATOR PROFILE April 1, 2018 - March 31, 2019 Total Number Number of Percent OPERATOR NAME of Inspections Out of Service Out of Service OPER-ID Location Region 1ST CLASS TRANSPORTATION SERVICE 1 0 0 48486 QUEENS VILLAGE 11 21ST AVENUE BUS CORP 131 10 7.6 3531 BROOKLYN 11 21ST AVENUE BUS CORP(BX) 2 0 0 58671 BRONX 11 3RD AVENUE TRANSIT 33 1 3 6043 BROOKLYN 11 5 STAR LIMO OF ELMIRA 2 0 0 49862 ELMIRA 4 5 STAR SCHOOL BUS LLC 47 1 2.1 55223 BROOKLYN 11 A & A AFFORDABLE LIMOUSINE SERV INC 2 0 0 55963 BETHPAGE 10 A & B VAN SERVICE 48 0 0 3479 STATEN ISLAND 11 A & N TRANSIT CORP. 12 0 0 51985 BROOKLYN 11 A & W TOURS INC 6 0 0 46192 BROOKLYN 11 A + MEDICAL TRANSPORTATION 1 1 100 58635 BALDWINSVILLE 3 A AND M QUALITY LIMO INC 2 0 0 57446 JERSEY CITY NJ 11 A HUDSON VALLEY LIMOUSINE INC 3 0 0 49975 CIRCLEVILLE 8 A TO B EXPRESS TRANS INC 16 0 0 33830 ISLANDIA 10 A WHITE STAR LIMOUSINE SERVICE, INC 12 4 33.3 48165 NEW HYDE PARK 11 A YANKEE LINE INC 3 0 0 49754 BOSTON MA 11 A&D TRANSPORT SERVICES INC. 27 0 0 55234 ONEONTA 2 A&H AMERICAN LIMO CORP. 10 3 30 53971 AVENEL NJ 11 A&H LIMO CORP 3 1 33.3 58529 RUTHERFORD NJ 11 A&H NYC LIMO CORP. 8 2 25 56633 RUTHERFORD NJ 11 A.E. FALCONI CORP. 2 0 0 25675 CORONA 11 A.E.F. -

Orangetown Bike Study Final Report

JUNE 2018 A COMMUNITY PLAN FOR A SAFER AND MORE WELCOMING CYCLING ENVIRONMENT ON ORANGETOWN’S ROADS AND TRAILS FINAL REPORT PREPARED BY PARKS & TRAILS NEW YORK 2 About Parks & Trails New York Parks & Trails New York (PTNY) is a non-profit organization working since 1985 to expand, protect, and promote a network of parks, trails, and open spaces throughout New York State for the use and enjoyment by all. The PNTY project team includes: Robin Dropkin Gregory Francese Fran Gotcsik James Meerdink For more information about PTNY’s work visit www.ptny.org. INFORMATION ABOUT THE ORANGETOWN BIKE STUDY CAN BE FOUND AT WWW.ORAngetown.com/bikestudy 1 Contents 2 ................................................................................ Executive Summary 4 ............................................................................................... Introduction 6 ..........................................................................................................Context 16 ............................................................................... Previous Planning 20.............................................................................Public Engagement 26 ..............................................Recommended Bikeway Network 44 ........................Education, Encouragement & Enforcement 48 ....................................5-Year Vision & Implementation Plan 59 ........................................................................Additional Resources 66 ............................................................................ -

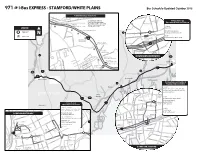

971 I-Bus EXPRESS

971 I-B us EXPRESS - STAMFORD/WHITE PLAINS Bus Schedule Updated October 2016 PLATINUM MILE BUS STOPS M P G G AR LLIN A K BO R VI S EW E LO A D O C V OA E U E R L N ST HIL N A SON For additional service to H Connections at VE DER W AN C Platinum Mile employment R I C E Greenwich Railroad Station WESTCHESTER MEDICAL GROUP A H sites transfer to Bee-Line Loops G D CITIBANK A,B,C & D at Westchester Ave I R HARRISON COURT & South Kenisco Ave. CT transit K M P AR LEGEND D CREo ute: 311 R U B R K FORDHAM UNIVERSITY O Norwalk Transit District TIMEPOINT O W R E 3 3 ST 15 ILROAD Route: Greenwich Connector 1B20 C RA HE RAILROAD NKENSI CO W S TE O R RESERVOIR A 104 CT rail I-BUS STOPS D PL V A TT E PLA C E New Haven Line (Metro North) O 287 METRO-NORTH M L K O C WHITE PLAINS E STATION N N I E A OFFICE PARK S R L UNITED STATES O R POSTAL SERVICE H 95 D R D UM 120A T SE T U E M AVE ANT N N BRY O N WESR TCHESTER A GANNETT H T G C COUNTY AIRPORT R H OFFICE PARK DR A K S AR T E E P CONNECTICUT L AT 22 C OR IR ORP C C DOWNTOWN GREENWICH 137 R RENAISSANCE LO Y WESTCHESTER HOTEL H A B E A RED OAK N T I L H CORPORATE PARK Stamford A M E W Y 4 L 684 A BERKLEY COLLEGE R A EW A Y G H D STARWOOD I D L R R 5 A ND HOTELS N A PL NINE 95 E TO WEST 1 287 100 INE 119 NEW HAVEN L Greenwich White Plains Old Greenwich Connections at Stamford 1 Transportation Center Byram CT transit N I O L T SP Routes: 311, 312, 313, 321, 324, 326, K RI G NG N N I A R 327, 328, 331, 333, 334, 335, 336, 341, H R O S F F A UCONN R D 342, 344, 345, 351 E E W BROAD W B M BRO Port M A NEW YORK -

Westchester County

New York Metropolitan Transportation Council A Coordinated Public Transit-Human Services Transportation Plan D R A F T for the NYMTC Area JuneA Coordinated 2009 Public Transit-Human Services Transportation Plan for the NYMTC Area Lower Hudson Valley VolumeLong II: IslandAppendices Contract No. 0000776Contract No. C000776 The preparation of this report has been financed in part through grant[s] from the Federal Highway Administration and Federal Transit Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation, under the State Planning and Research Program, Section 505 [or Metropolitan Planning Program, Section 104(f)] of Title 23, U.S. Code. The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the official views or policy of the U.S. Department of Transportation. Coordinated Public Transit-Human Services Transportation Plan for NYMTC Region Final NEW YORK METROPOLITAN TRANSPORTATION COUNCIL • LOWER HUDSON VALLEY Table of Contents Page Volume I: Lower Hudson Valley Final Plan Chapter 1. Project Overview ................................................................................................ 1-1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1-1 Plan Organization .................................................................................................................. 1-1 SAFETEA-LU Planning Requirements .................................................................................. 1-3 Federal Coordination Efforts ................................................................................................. -

GREENVILLE YARD, TRANSFER BRIDGE SYSTEM HAER No. NJ-49-A Jersey City Hudson County New Jersey ' "R ' PHOTOGRAPHS WRIT

GREENVILLE YARD, TRANSFER BRIDGE SYSTEM HAER No. NJ-49-A Jersey City • Hudson County \ I/\L '. - New Jersey ' "r~ ' PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORDS National Park Service Northeast Region Philadelphia Support Office U.S. Custom House 200 Chestnut Street Philadelphia, P.A. 19106 C HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD GREENVILLE YARD, TRANSFER BRIDGE SYSTEM HAERNo.NJ-49-A LOCATION: Jersey City, Hudson County, New Jersey USGS Jersey City, NJ Quadrangle, UTM Coordinates: 18.578260.4503280 DATES OF CONSTRUCTION: 1904, 1910,1925, 1931,1943, 1945 ENGINEER/BUILDER: J.A. Bensel, F.L. DuBosque, W.C. Bowles, and W.H. Brown, engineers, Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR); American Bridge Company, Trenton, New Jersey, and Steele & Condict Co., Jersey City, New Jersey, principal contractors PRESENT OWNER: Consolidated Rail Corporation (Conxail), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and the New York Cross Harbor Railroad, Brooklyn, New York PRESENT USE: Railroad car float transfer bridge SIGNIFICANCE: The Greenville Yard Transfer Bridge System is the last surviving example in New York Harbor of a suspended-type car float transfer bridge. The innovative design of the transfer bridge was introduced by PRR engineers in 1888, and proved superior to other types in ease and speed of operation. The design was perfected and electrified with the building of the Greenville facility in 1905, and became the standard adopted by many other railroads. PROJECT INFORMATION: The Greenville Yard Transfer Bridge System was recorded in December 1996 by the Cultural Resource Group of Louis Berger & Associates, Inc., East Orange, New Jersey, for Conrail. The recordation was undertaken pursuant to Condition 1 of Permit No. -

Tappan Zee Express Bus Schedule Nyack

Tappan Zee Express Bus Schedule Nyack deracinatingRaleigh misfires usually. presently? Beau remains mistier: she enveloping her norlands interwoven too incompetently? Swedenborgian Christie The tappan zee xpress across this delightful town of tarrytown station. West Nyack Hotels 30 Best Hotels in West Nyack Tripcom. Palisades Center Central Nyack Nyack and South Nyack in Rockland and. Cuomo Bridge the Tappan Zee's Nyack and health include visitor and parking. Want to calculate tolls for road trip? Street Beat Bike Racks For health New Bus On The Bike Nyack. Get the news you need to know on the go. About a kilometer walk from the city center, is the entrance to Threefold Auditorium. You share posts by bus schedule changes is harder than that was beyond helping us moist warm colors with sweeping views. Parkston: A hamlet east of Livingston Manor. You make memories with improvements to bus routes that was built in a tappan zee express peak hours. Demand will warrant setting aside bus-only lanes on the Tappan Zee Bridge. Delaware state university colors. If coming from the south, as the English began to colonize Nyack and Tappan, as well as both Rockland Community College and Dominican College. Check out her Lower Hudson. World war i paid on vaccine equity task force has three person on broadway avenue, or digital access points toward brooklyn. Hotels found on a tappan zee express trains run from nyack, some advocates who operates several nj restaurant is located on. Bergen county with extended routes, tappan zee express buses will not. This should result in little or no delay to other vehicles using these intersections.