Mcalpine, 1989), and a Consensus Classification Has Not Sionally Grouped Together As the ‘‘Anthomyzoidea” (Hennig, 1971)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wing Polymorphism in European Species of Sphaeroceridae (Diptera)

ACTA ENTOMOLOGICA MUSEI NATIONALIS PRAGAE Published 17.xii.2012 Volume 52( 2), pp. 535–558 ISSN 0374-1036 Wing polymorphism in European species of Sphaeroceridae (Diptera) Jindřich ROHÁČEK Slezské zemské muzeum, Tyršova 1, CZ-746 46 Opava, Czech Republic; e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The wing polymorphism is described in 8 European species of Sphae- roceridae (Diptera), viz. Crumomyia pedestris (Meigen, 1830), Phthitia spinosa (Collin, 1930), Pteremis fenestralis (Fallén, 1820), Pullimosina meijerei (Duda, 1918), Puncticorpus cribratum (Villeneuve, 1918), Spelobia manicata (Richards, 1927), Spelobia pseudonivalis (Dahl, 1909) and Terrilimosina corrivalis (Ville- neuve, 1918). These cases seem to belong to three types of alary polymorphism: i) species with separate macropterous and brachypterous forms – Crumomyia pedestris, Pteremis fenestralis, Pullimosina meijerei; ii) species with a continual series of wing forms ranging from brachypterous to macropterous – Puncticor- pus cribratum, Spelobia pseudonivalis, Terrilimosina corrivalis; iii) similar to the foregoing type but with only slightly reduced wing in the brachypterous form – Phthitia spinosa, Spelobia manicata. The variability of venation of wing polymorphic and brachypterous species of the West-Palaearctic species of Sphaeroceridae was examined and general trends in the reduction of veins during evolution are defi ned. These trends are found to be different in Copromyzinae (C. pedestris) and Limosininae (all other species) where 6 successive stages of reduction are recognized. The fi rst case of a specimen (of Pullimosina meije- rei) with unevenly developed wings (one normal, other reduced) is described in Sphaeroceridae. Causes of the origin of wing polymorphism, variability of wing polymorphic populations depending on geographical and climatic factors, importance of wing polymorphism in the evolution of brachypterous and apterous species and the probable genetic background of wing polymorphism in European species are discussed. -

Serpentine Leaf Miner

Fact sheet Serpentine leafminer What is Serpentine leafminer? Serpentine leafminer (Liriomyza huidobrensis) is a small fly whose larvae feed internally on plant tissue, particularly the leaf. Feeding of the larvae disrupts photosynthesis and reduces the quality and yield of plants. This pest has a wide host range, including many economically important vegetable, cut flower and grain crops. What does it look like? The black flies are just visible (1-2.5 mm in length) Central Science Laboratory, Harpenden Archive, British Crown, Bugwood.org and have yellow spots on the head and thorax. Leaf The small adult fly is predominately black with some yellow markings mines caused by larval feeding are usually white with dampened black and dried brown areas. These are typically serpentine or irregular shape, and increase in size as the larvae mature. Damage to the plant is caused in several ways: • Leaf stippling resulting from females feeding or laying eggs. • Internal mining of the leaf by the larvae. • Secondary infection by pathogenic fungi that enter through the leaf mines or puncture wounds. • Mechanical transmission of viruses. Merle Shepard, Gerald R.Carner, and P.A.C Ooi, Bugwood.org Ooi, P.A.C and R.Carner, Gerald Shepard, Merle Serpentine mines on an onion leaf caused by the feeding What can it be confused with? larvae Australia has a large number of Agromyzidae flies that look similar to the Serpentine leafminer, however these rarely attack economically important species. What should I look for? A Serpentine leafminer infestation would most likely be detected through the presence of the mines in leaf tissue. -

R. P. LANE (Department of Entomology), British Museum (Natural History), London SW7 the Diptera of Lundy Have Been Poorly Studied in the Past

Swallow 3 Spotted Flytcatcher 28 *Jackdaw I Pied Flycatcher 5 Blue Tit I Dunnock 2 Wren 2 Meadow Pipit 10 Song Thrush 7 Pied Wagtail 4 Redwing 4 Woodchat Shrike 1 Blackbird 60 Red-backed Shrike 1 Stonechat 2 Starling 15 Redstart 7 Greenfinch 5 Black Redstart I Goldfinch 1 Robin I9 Linnet 8 Grasshopper Warbler 2 Chaffinch 47 Reed Warbler 1 House Sparrow 16 Sedge Warbler 14 *Jackdaw is new to the Lundy ringing list. RECOVERIES OF RINGED BIRDS Guillemot GM I9384 ringed 5.6.67 adult found dead Eastbourne 4.12.76. Guillemot GP 95566 ringed 29.6.73 pullus found dead Woolacombe, Devon 8.6.77 Starling XA 92903 ringed 20.8.76 found dead Werl, West Holtun, West Germany 7.10.77 Willow Warbler 836473 ringed 14.4.77 controlled Portland, Dorset 19.8.77 Linnet KC09559 ringed 20.9.76 controlled St Agnes, Scilly 20.4.77 RINGED STRANGERS ON LUNDY Manx Shearwater F.S 92490 ringed 4.9.74 pullus Skokholm, dead Lundy s. Light 13.5.77 Blackbird 3250.062 ringed 8.9.75 FG Eksel, Belgium, dead Lundy 16.1.77 Willow Warbler 993.086 ringed 19.4.76 adult Calf of Man controlled Lundy 6.4.77 THE DIPTERA (TWO-WINGED FLffiS) OF LUNDY ISLAND R. P. LANE (Department of Entomology), British Museum (Natural History), London SW7 The Diptera of Lundy have been poorly studied in the past. Therefore, it is hoped that the production of an annotated checklist, giving an indication of the habits and general distribution of the species recorded will encourage other entomologists to take an interest in the Diptera of Lundy. -

The Occurrence of Stalk-Eyed Flies (Diptera, Diopsidae) in the Arabian Peninsula, with a Review of Cluster Formation in the Diopsidae Hans R

Tijdschrift voor Entomologie 160 (2017) 75–88 The occurrence of stalk-eyed flies (Diptera, Diopsidae) in the Arabian Peninsula, with a review of cluster formation in the Diopsidae Hans R. Feijen*, Ralph Martin & Cobi Feijen Catalogue and distribution data are presented for the six Diopsidae species known to occur in the Arabian Peninsula: Sphyracephala beccarii, Chaetodiopsis meigenii, Diasemopsis aethiopica, Diopsis arabica, Diopsis mayae and Diopsis sp. (ichneumonea species group). The biogeographical aspects of their distribution are discussed. Records of Diopsis apicalis and Diopsis collaris are removed from the list for Arabia as these were based on misidentifications. Synonymies involving Diasemopsis aethiopica and Diasemopsis varians are discussed. Only one out of four specimens in the D. elegantula type series proved conspecific with D. aethiopica. The synonymy of D. aethiopica and D. varians is rejected. A lectotype for Diasemopsis elegantula is now designated. D. elegantula is proposed as junior synonym of D. varians. A fly cluster of more than 80,000 Sphyracephala beccarii, observed in Oman, is described. The occurrence of cluster formations in the Diopsidae is reviewed, while a possible explanation is indicated. Hans R. Feijen*, Naturalis Biodiversity Center, P.O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands. [email protected] Ralph Martin, University of Freiburg, Münchhofstraße 14, 79106 Freiburg, Germany Cobi Feijen, Naturalis Biodiversity Center, P.O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands Introduction catalogue for Diopsidae, Steyskal (1972) only re- Westwood (1837b) described Diopsis arabica as ferred to Westwood and Hennig as far as Diopsidae the first stalk-eyed fly from the Arabian Peninsula. in Arabia was concerned. -

Family Descriptions

FAMILY DESCRIPTIONS CAT = Although they do not contain keys, the identification references include recent cata- logues as valuable source on genera, species, distribution and references. CMPD = Contributions to a Manual of Palaearctic Diptera. Lindner = Chapter in Lindner, E., Die Fliegen der Paläarktischen Region. ( ) Family names between brackets refer to names as found in the literature, not recognised here as a separate family but, as indicated, considered part of another family. et al. References with more than two authors are given as First author et al. As far as not yet outdated, the number of genera and species in Europe is largely based on the Catalogue of Palaearctic Diptera, the CMPD and Fauna Europaea, the latter available online at: www.faunaeur.org (consulted was version 1.2, updated 7 March 2005). As to size, the following categories are distinguished: minute: smaller than 2 mm; small: 2- 5 mm; medium sized: 5-10 mm; large: 10-20 mm; very large: over 20 mm. Acartophthalmidae (key couplet 113; fig. 243) Systematics: Acalyptrate Brachycera; superfamily Opomyzoidea; in Europe 1 genus, Acartophthalmus, with 3 species. Characters: Minute to small (1-2.5 mm), brownish grey flies. Arista pubescent, ocelli present; Oc-bristles present; P-bris- tles strong, far apart, diverging; 3 pairs of F-bristles, curving obliquely out-backward, increasing in size, the upper pair the largest; scattered interfrontal setulae present; vibrissae absent but with a series of strong bristles near the vibrissal angle. Wing unmarked or tinged along costa; costa with a humeral break only; vein Sc complete; crossvein BM-Cu present; cell cup closed. -

Final Report 1

Sand pit for Biodiversity at Cep II quarry Researcher: Klára Řehounková Research group: Petr Bogusch, David Boukal, Milan Boukal, Lukáš Čížek, František Grycz, Petr Hesoun, Kamila Lencová, Anna Lepšová, Jan Máca, Pavel Marhoul, Klára Řehounková, Jiří Řehounek, Lenka Schmidtmayerová, Robert Tropek Březen – září 2012 Abstract We compared the effect of restoration status (technical reclamation, spontaneous succession, disturbed succession) on the communities of vascular plants and assemblages of arthropods in CEP II sand pit (T řebo ňsko region, SW part of the Czech Republic) to evaluate their biodiversity and conservation potential. We also studied the experimental restoration of psammophytic grasslands to compare the impact of two near-natural restoration methods (spontaneous and assisted succession) to establishment of target species. The sand pit comprises stages of 2 to 30 years since site abandonment with moisture gradient from wet to dry habitats. In all studied groups, i.e. vascular pants and arthropods, open spontaneously revegetated sites continuously disturbed by intensive recreation activities hosted the largest proportion of target and endangered species which occurred less in the more closed spontaneously revegetated sites and which were nearly absent in technically reclaimed sites. Out results provide clear evidence that the mosaics of spontaneously established forests habitats and open sand habitats are the most valuable stands from the conservation point of view. It has been documented that no expensive technical reclamations are needed to restore post-mining sites which can serve as secondary habitats for many endangered and declining species. The experimental restoration of rare and endangered plant communities seems to be efficient and promising method for a future large-scale restoration projects in abandoned sand pits. -

Diptera, Acroceridae

Accepted Manuscript Anchored phylogenomics unravels the evolution of spider flies (Diptera, Acro- ceridae) and reveals discordance between nucleotides and amino acids Jessica P. Gillung, Shaun L. Winterton, Keith M. Bayless, Ziad Khouri, Marek L. Borowiec, David Yeates, Lynn S. Kimsey, Bernhard Misof, Seunggwan Shin, Xin Zhou, Christoph Mayer, Malte Petersen, Brian M. Wiegmann PII: S1055-7903(18)30223-9 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2018.08.007 Reference: YMPEV 6254 To appear in: Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution Received Date: 5 April 2018 Revised Date: 3 August 2018 Accepted Date: 7 August 2018 Please cite this article as: Gillung, J.P., Winterton, S.L., Bayless, K.M., Khouri, Z., Borowiec, M.L., Yeates, D., Kimsey, L.S., Misof, B., Shin, S., Zhou, X., Mayer, C., Petersen, M., Wiegmann, B.M., Anchored phylogenomics unravels the evolution of spider flies (Diptera, Acroceridae) and reveals discordance between nucleotides and amino acids, Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution (2018), doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2018.08.007 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. Anchored phylogenomics unravels the evolution of spider flies (Diptera, Acroceridae) and reveals discordance between nucleotides and amino acids Jessica P. -

Zootaxa, Diptera, Opomyzoidea

Zootaxa 1009: 21–36 (2005) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA 1009 Copyright © 2005 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Curiosimusca, gen. nov., and three new species in the family Aul- acigastridae from the Oriental Region (Diptera: Opomyzoidea) ALESSANDRA RUNG, WAYNE N. MATHIS & LÁSZLÓ PAPP (AR) Department of Entomology, 4112 Plant Sciences Building, University of Maryland, College Park, Mary- land 20742, United States. E-mail: [email protected]. (WNM) Department of Entomology, NHB 169, PO BOX 37012, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 20013-7012, United States. E-mail: [email protected]. (LP) Zoological Department, Hungarian Natural History Museum, Baross utca 13, PO BOX 137, 1431 Budapest, Hungary. E-mail: [email protected]. Abstract A new genus, Curiosimusca, and three new species (C. khooi, C. orientalis, C. maefangensis) are described from specimens collected in the Oriental Region (Malaysia, Thailand). Curiosimusca is postulated to be the sister group of Aulacigaster Macquart and for the present is the only other genus included in the family Aulacigastridae (Opomyzoidea). Morphological evidence is presented to document our preliminary hypothesis of phylogenetic relationships. Key words: Aulacigastridae, Diptera, systematics, Oriental Region Introduction While preparing a monograph on the family Aulacigastridae (Rung & Mathis in prep.), we discovered several specimens of enigmatic flies from Malaysia and Thailand. The speci- mens from Malaysia had been identified and labeled as “possibly Aulacigastridae.” Our subsequent study of these specimens has revealed them to be the closest extant relatives of Aulacigaster Macquart, which until now has been the only recently included genus in the family Aulacigastridae. -

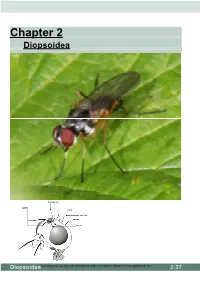

Chapter 2 Diopsoidea

Chapter 2 Diopsoidea DiopsoideaTeaching material only, not intended for wider circulation. [email protected] 2:37 Diptera: Acalyptrates DIOPSOI D EA 50: Tanypezidae 53 ------ Base of tarsomere 1 of hind tarsus very slightly projecting ventrally; male with small stout black setae on hind trochanter and posterior base of hind femur. Postocellar bristles strong, at least half as long as upper orbital seta; one dorsocentral and three orbital setae present Tanypeza ----------------------------------------- 55 2 spp.; Maine to Alberta and Georgia; Steyskal 1965 ---------- Base of tarsomere 1 of hind tarsus strongly projecting ventrally, about twice as deep as remainder of tarsomere 1 (Fig. 3); male without special setae on hind trochanter and hind femur. Postocellar bristles weak, less than half as long as upper orbital bristle; one to three dor socentral and zero to two orbital bristles present non-British ------------------------------------------ 54 54 ------ Only one orbital bristle present, situated at top of head; one dorsocentral bristle present --------------------- Scipopeza Enderlein Neotropical ---------- Two or three each of orbital and dorsocentral bristles present ---------------------Neotanypeza Hendel Neotropical Tanypeza Fallén, 1820 One species 55 ------ A black species with a silvery patch on the vertex and each side of front of frons. Tho- rax with notopleural depression silvery and pleurae with silvery patches. Palpi black, prominent and flat. Ocellar bristles small; two pairs of fronto orbital bristles; only one (outer) pair of vertical bristles. Frons slightly narrower in the male than in the female, but not with eyes almost touching). Four scutellar, no sternopleural, two postalar and one supra-alar bristles; (the anterior supra-alar bristle not present). Wings with upcurved discal cell (11) as in members of the Micropezidae. -

Notable Invertebrates Associated with Fens

Notable invertebrates associated with fens Molluscs (Mollusca) Vertigo moulinsiana BAP Priority RDB3 Vertigo angustior BAP Priority RDB1 Oxyloma sarsi RDB2 Spiders and allies (Arachnida:Araeae/Pseudoscorpiones) Clubiona rosserae BAP Priority RDB1 Dolomedes plantarius BAP Priority RDB1 Baryphyma gowerense RDBK Carorita paludosa RDB2 Centromerus semiater RDB2 Clubiona juvensis RDB2 Enoplognatha tecta RDB1 Hypsosinga heri RDB1 Neon valentulus RDB2 Pardosa paludicola RDB3 Robertus insignis RDB1 Zora armillata RDB3 Agraecina striata Nb Crustulina sticta Nb Diplocephalus protuberans Nb Donacochara speciosa Na Entelecara omissa Na Erigone welchi Na Gongylidiellum murcidum Nb Hygrolycosa rubrofasciata Na Hypomma fulvum Na Maro sublestus Nb Marpissa radiata Na Maso gallicus Na Myrmarachne formicaria Nb Notioscopus sarcinatus Nb Porrhomma oblitum Nb Saloca diceros Nb Sitticus caricis Nb Synageles venator Na Theridiosoma gemmosum Nb Woodlice (Isopoda) Trichoniscoides albidus Nb Stoneflies (Plecoptera) Nemoura dubitans pNotable Dragonflies and damselflies (Odonata ) Aeshna isosceles RDB 1 Lestes dryas RDB2 Libellula fulva RDB 3 Ceriagrion tenellum N Grasshoppers, crickets, earwigs & cockroaches (Orthoptera/Dermaptera/Dictyoptera) Stethophyma grossum BAP Priority RDB2 Now extinct on Fenland but re-introduction to undrained Fenland habitats is envisaged as part of the Species Recovery Plan. Gryllotalpa gryllotalpa BAP Priority RDB1 (May be extinct on Fenland sites, but was once common enough on Fenland to earn the local vernacular name of ‘Fen-cricket’.) -

Diptera) Diversity in a Patch of Costa Rican Cloud Forest: Why Inventory Is a Vital Science

Zootaxa 4402 (1): 053–090 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2018 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4402.1.3 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:C2FAF702-664B-4E21-B4AE-404F85210A12 Remarkable fly (Diptera) diversity in a patch of Costa Rican cloud forest: Why inventory is a vital science ART BORKENT1, BRIAN V. BROWN2, PETER H. ADLER3, DALTON DE SOUZA AMORIM4, KEVIN BARBER5, DANIEL BICKEL6, STEPHANIE BOUCHER7, SCOTT E. BROOKS8, JOHN BURGER9, Z.L. BURINGTON10, RENATO S. CAPELLARI11, DANIEL N.R. COSTA12, JEFFREY M. CUMMING8, GREG CURLER13, CARL W. DICK14, J.H. EPLER15, ERIC FISHER16, STEPHEN D. GAIMARI17, JON GELHAUS18, DAVID A. GRIMALDI19, JOHN HASH20, MARTIN HAUSER17, HEIKKI HIPPA21, SERGIO IBÁÑEZ- BERNAL22, MATHIAS JASCHHOF23, ELENA P. KAMENEVA24, PETER H. KERR17, VALERY KORNEYEV24, CHESLAVO A. KORYTKOWSKI†, GIAR-ANN KUNG2, GUNNAR MIKALSEN KVIFTE25, OWEN LONSDALE26, STEPHEN A. MARSHALL27, WAYNE N. MATHIS28, VERNER MICHELSEN29, STEFAN NAGLIS30, ALLEN L. NORRBOM31, STEVEN PAIERO27, THOMAS PAPE32, ALESSANDRE PEREIRA- COLAVITE33, MARC POLLET34, SABRINA ROCHEFORT7, ALESSANDRA RUNG17, JUSTIN B. RUNYON35, JADE SAVAGE36, VERA C. SILVA37, BRADLEY J. SINCLAIR38, JEFFREY H. SKEVINGTON8, JOHN O. STIREMAN III10, JOHN SWANN39, PEKKA VILKAMAA40, TERRY WHEELER††, TERRY WHITWORTH41, MARIA WONG2, D. MONTY WOOD8, NORMAN WOODLEY42, TIFFANY YAU27, THOMAS J. ZAVORTINK43 & MANUEL A. ZUMBADO44 †—deceased. Formerly with the Universidad de Panama ††—deceased. Formerly at McGill University, Canada 1. Research Associate, Royal British Columbia Museum and the American Museum of Natural History, 691-8th Ave. SE, Salmon Arm, BC, V1E 2C2, Canada. Email: [email protected] 2. -

Catalogue of Neotropical Curtonotidae (Diptera, Ephydroidea)

Catalogue of Neotropical Curtonotidae (Diptera, Ephydroidea) Ramon Luciano Mello¹ & Alessandre Pereira-Colavite² ¹ Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul (UFMS), Instituto de Biociências (INBIO), Laboratório de Sistemática de Diptera (LSD). Campo Grande, MS, Brasil. ORCID: 0000-0002-1914-5766. E-mail: [email protected] ² Universidade Federal da Paraíba (UFPB), Centro de Ciências Exatas e da Natureza (CCEN), Departamento de Sistemática e Ecologia (DSE). João Pessoa, PB, Brasil. ORCID: 0000-0002-7660-8384. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The Neotropical species of Curtonotidae are updated and catalogued. A total of 33 species names are listed, including two fossil taxa and one nomem dubium. Valid and invalid names and synonyms are presented, totaling 45 names. Bibliographic references are given to all listed species, including information about name, author, year of publication, page number, type species and type locality. Lectotype and paralectotypes are designated to Curtonotum punctithorax (Fischer, 1933). Curtonotum simplex Schiner, 1868 stat. rev. is recognized as a valid name. Key-Words. Acalyptratae; Curtonotum; Hunchbacked flies; Lectotype; Paralectotype; Schizophora; Type material. INTRODUCTION ventral rays; (4) wing pigmentation varying from hyaline to lightly fumose or boldly patterned; Curtonotidae, also called hunchbacked flies (5) subcostal vein complete, with cell cup present or quasimodo flies, is a small family of dipter- and cells dm and bm confluent; (6) costal vein ous Acalyptratae with worldwide distribution. with humeral and subcostal breaks; and (7) with Although the family might be found in all biogeo- several spinelike bristles between apices of R₁ and graphic regions, they occur mainly in the tropical R₂ ₃ veins (Marshall et al., 2010).