The Revolution from Within

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

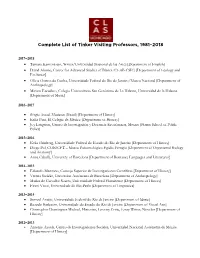

Complete List of Tinker Visiting Professors, 1981–2018

Complete List of Tinker Visiting Professors, 1981–2018 2017–2018 • Tamara Kamenszain, Writer/Universidad Nacional de las Artes [Department of English] • David Alonso, Center for Advanced Studies of Blanes (CEAB-CSIC) [Department of Ecology and Evolution] • Olívia Gomes da Cunha, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro/Museu Nacional [Department of Anthropology] • Miriam Escudero, Colegio Universitario San Gerónimo de La Habana, Universidad de la Habana [Department of Music] 2016–2017 • Sérgio Assad, Musician (Brazil) [Department of History] • Erika Pani, El Colegio de México [Department of History] • Joy Langston, Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas, Mexico [Harris School of Public Policy] 2015–2016 • Keila Grinberg, Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro [Department of History] • Diego Pol, CONICET – Museo Paleontológico Egidio Feruglio [Department of Organismal Biology and Anatomy] • Anna Caballé, University of Barcelona [Department of Romance Languages and Literatures] 2014–2015 • Eduardo Manzano, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas [Department of History] • Verena Stolcke, Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona [Department of Anthropology] • Mariza de Carvalho Soares, Universidade Federal Fluminense [Department of History] • Evani Viotti, Universidade de São Paulo [Department of Linguistics] 2013–2014 • Samuel Araújo, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro [Department of Music] • Ricardo Basbaum, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro [Department of Visual Arts] • Christopher Domínguez Michael, Historian, -

The Rhetoric of Fidel Castro Brent C

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2008 From the mountains to the podium: the rhetoric of Fidel Castro Brent C. Kice Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Kice, Brent C., "From the mountains to the podium: the rhetoric of Fidel Castro" (2008). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1766. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1766 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. FROM THE MOUNTAINS TO THE PODIUM: THE RHETORIC OF FIDEL CASTRO A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Communication Studies by Brent C. Kice B.A., Loyola University New Orleans, 2002 M.A., Southeastern Louisiana University, 2004 December 2008 DEDICATION To my wife, Dori, for providing me strength during this arduous journey ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Andy King for all of his guidance, and especially his impeccable impersonations. I also wish to thank Stephanie Grey, Ruth Bowman, Renee Edwards, David Lindenfeld, and Mary Brody for their suggestions during this project. I am so thankful for the care and advice given to me by Loretta Pecchioni. -

Tenth Conference on Cuban and Cuban-American Studies

Cuban Research Institute School of International and Public Affairs Tenth Conference on Cuban and Cuban-American Studies “More Than White, More Than Mulatto, More Than Black”: Racial Politics in Cuba and the Americas “Más que blanco, más que mulato, más que negro”: La política racial en Cuba y las Américas Dedicated to Carmelo Mesa-Lago February 26-28, 2015 WELCOMING REMARKS I’m thrilled to welcome you to our Tenth Conference on Cuban and Cuban-American Studies. On Friday evening, we’ll sponsor the premiere of the PBS documentary Cuba: The Forgotten Organized by the Cuban Research Institute (CRI) of Florida International University (FIU) Revolution, directed by Glenn Gebhard. The film focuses on the role of the slain leaders since 1997, this biennial meeting has become the largest international gathering of scholars José Antonio Echeverría and Frank País in the urban insurrection movement against the specializing in Cuba and its diaspora. Batista government in Cuba during the 1950s. After the screening, Lillian Guerra will lead the discussion with the director; Lucy Echeverría, José Antonio’s sister; Agustín País, Frank’s As the program for our conference shows, the academic study of Cuba and its diaspora brother; and José Álvarez, author of a book about Frank País. continues to draw substantial interest in many disciplines of the social sciences and the humanities, particularly in literary criticism, history, anthropology, sociology, music, and the On Saturday, the last day of the conference, we’ll have a numerous and varied group of arts. We expect more than 250 participants from universities throughout the United States and presentations. -

Uneasy Intimacies: Race, Family, and Property in Santiago De Cuba, 1803-1868 by Adriana Chira

Uneasy Intimacies: Race, Family, and Property in Santiago de Cuba, 1803-1868 by Adriana Chira A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Jesse E. Hoffnung-Garskof, Co-Chair Professor Rebecca J. Scott, Co-Chair Associate Professor Paulina L. Alberto Professor Emerita Gillian Feeley-Harnik Professor Jean M. Hébrard, École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales Professor Martha Jones To Paul ii Acknowledgments One of the great joys and privileges of being a historian is that researching and writing take us through many worlds, past and present, to which we become bound—ethically, intellectually, emotionally. Unfortunately, the acknowledgments section can be just a modest snippet of yearlong experiences and life-long commitments. Archivists and historians in Cuba and Spain offered extremely generous support at a time of severe economic challenges. In Havana, at the National Archive, I was privileged to get to meet and learn from Julio Vargas, Niurbis Ferrer, Jorge Macle, Silvio Facenda, Lindia Vera, and Berta Yaque. In Santiago, my research would not have been possible without the kindness, work, and enthusiasm of Maty Almaguer, Ana Maria Limonta, Yanet Pera Numa, María Antonia Reinoso, and Alfredo Sánchez. The directors of the two Cuban archives, Martha Ferriol, Milagros Villalón, and Zelma Corona, always welcomed me warmly and allowed me to begin my research promptly. My work on Cuba could have never started without my doctoral committee’s support. Rebecca Scott’s tireless commitment to graduate education nourished me every step of the way even when my self-doubts felt crippling. -

Race, Empire and Leisure in the Caribbean & United States

Lillian Guerra, Ph.D. Office: Grinter 307 Professor of Cuban & Caribbean History [email protected] TA: Lauren Krebs, M.A. TA: [email protected] Office phone: 352-273-3375 Office Hours: Th 12-2 PM Race, Empire and Leisure in the Caribbean & United States Course details Class Meetings with Prof. Guerra: T/Th 8:30-9:20 AM in MAT 0018 Class Meetings with Ms. Krebs: Please note the section for which you signed up. • Section 12AF Th 11:45-12:35 in TUR 2322 • Section 12AA Th 12:50-1:40 in FLI 0119 • Section 1199 Th 1:55-2:45 in TUR 2305 Quest 1 Theme: Identities General Education Requirements: Humanities, Writing and Diversity Course costs: Purchase (in hard copy) of the following list of required books. Printing of additional materials provided electronically via course website on Canvas. All students must have hard (paper) copies of materials for in-class discussion and personal use. Required books: • Frances Negrón-Muntaner, Boricua Pop: Puerto Ricans and the Latinization of American Culture (New York University Press, 2004). • Esmeralda Santiago, When I Was Puerto Rican: A Memoir (Da Capo Press, 2006). • Junot Díaz, The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao (Riverside Books, 2008). • Achy Obejas, Memory Mambo (Cleis, 1996). Course description Focused on the Twentieth Century, this course analyzes the construction of Caribbean identities among transnational Caribbean communities that link Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic and Haiti to their US diasporas. We will study fictionalized memoirs, poetry, theatre, historical documents and the centrality of Caribbean identities to mainstream cultural ideas about the nature and racialized image of US identity. -

Cuban Leadership Overview, Apr 2009

16 April 2009 OpenȱSourceȱCenter Report Cuban Leadership Overview, Apr 2009 Raul Castro has overhauled the leadership of top government bodies, especially those dealing with the economy, since he formally succeeded his brother Fidel as president of the Councils of State and Ministers on 24 February 2008. Since then, almost all of the Council of Ministers vice presidents have been replaced, and more than half of all current ministers have been appointed. The changes have been relatively low-key, but the recent ousting of two prominent figures generated a rare public acknowledgement of official misconduct. Fidel Castro retains the position of Communist Party first secretary, and the party leadership has undergone less turnover. This may change, however, as the Sixth Party Congress is scheduled to be held at the end of this year. Cuba's top military leadership also has experienced significant turnover since Raul -- the former defense minister -- became president. Names and photos of key officials are provided in the graphic below; the accompanying text gives details of the changes since February 2008 and current listings of government and party officeholders. To view an enlarged, printable version of the chart, double-click on the following icon (.pdf): This OSC product is based exclusively on the content and behavior of selected media and has not been coordinated with other US Government components. This report is based on OSC's review of official Cuban websites, including those of the Cuban Government (www.cubagob.cu), the Communist Party (www.pcc.cu), the National Assembly (www.asanac.gov.cu), and the Constitution (www.cuba.cu/gobierno/cuba.htm). -

Ministerio De Salud Pública Area De Higiene Y Epidemiología

MINISTERIO DE SALUD PÚBLICA AREA DE HIGIENE Y EPIDEMIOLOGÍA Plan Multisectorial de Prevención de las ITS-VIH/sida Verano 2014 Introducción El Ministerio de Salud Pública a partir del mes de junio y hasta el 15 de septiembre desarrolla un plan de actividades para el verano, donde se refuerzan las medidas de control de enfermedades y riesgos para la salud de la población. Este año, en el marco de la celebración del Mundial de Fútbol a realizarse en Brasil, a nivel internacional se ha lanzado para la prevención de las ITS-VIH/sida, la iniciativa global “Protege la Meta” Infórmate, protégete, No discrimines, con el propósito de no perder de vista la meta de llegar a CERO nuevas infecciones por VIH, CERO muertes como consecuencia del sida y CERO discriminación por razón de vivir con esa condición. Objetivo general Contribuir a la reducción de las conductas sexuales de riesgo en poblaciones clave en el contexto del período vacacional. Objetivos específicos 1. Fomentar acciones de comunicación dirigidas hacia las poblaciones clave y la comunidad en general, para la adopción de conductas sexuales responsables, protegidas y de autocuidado utilizando la influencia y difusión del Mundial del Fútbol 2. Incrementar la capacitación, compromiso y vínculos con los comunicadores/as, periodistas y promotores/as de salud, así como especialistas y directivos/as de salud pública, relacionados con la prevención de las ITS-VIH/sida. Prioridades ◌ Infecciones de Transmisión Sexual: sífilis, gonorrea, condiloma y herpes genital. ◌ Infección por el VIH: incrementar la difusión de información acerca de la severidad de la infección por el VIH, la promoción del uso del condón y búsqueda activa de casos a través de actividades de “Hazte la prueba”. -

The Sixties Counterculture and Public Space, 1964--1967

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2003 "Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967 Jill Katherine Silos University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Silos, Jill Katherine, ""Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations. 170. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/170 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

10/2020 Curriculum Vitae MARIA ROSA OLIVERA-WILLIAMS

1 10/2020 Curriculum Vitae MARIA ROSA OLIVERA-WILLIAMS UNIVERSITY OF NOTRE DAME DEPARTMENT OF ROMANCE LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES NOTRE DAME, IN 46556 (574) 631-7268 E-MAIL: [email protected] 2013 PROFESSOR OF LATIN AMERICAN LITERATURE, Department of Romance Languages and Literatures, University of Notre Dame. 1988-present FACULTY FELLOW, Helen Kellogg Institute for International Studies. 2004-present FELLOW, Nanovic Institute for European Studies. EDUCATION Ph.D. Latin American and Peninsular Literatures (Presidential Award) The Ohio State University M.A. Latin American and Peninsular Literatures The Ohio State University, March B.A.S. Spanish (Magna Cum Laude) University of Toledo, Toledo, Ohio PUBLICATIONS Books Humanidades al límite: posiciones desde/contra la universidad global. Introduction and compilation. Co-edition with Cristián Opazo. Santiago, Chile: Cuarto Propio (2021 forthcoming). This volume studies from different perspectives and geographies the roles of Catholic universities to face the crisis of the Humanities in the midst of the challenges and opportunities offered by globalization. The volume reunites the work of distinguished historians, philosophers, literary and cultural studies colleagues at different stages in their careers. El arte de crear lo femenino: ficción, género e historia del Cono Sur. Santiago, Chile: Cuarto Propio, 2012. 257pp. https://www.cuartopropio.com/libro/el-arte-de-crear-lo-femenino/ The book is a theoretical and applied study of women’s social movements and fiction narratives during the second half of the twentieth century in the Southern Cone countries of Latin America, focusing on the post- suffragist period and the military dictatorship and post-dictatorship period. Reviewed by: Magdalena López. -

THE CUBAN REVOLUTION at 60 New Directions in History and Historiography

THE CUBAN REVOLUTION AT 60 New Directions in History and Historiography March 7-8 , New York University King Juan Carlos I Center Auditorium (53 Washington Square South, New York, NY 10012) THURSDAY, MARCH 7 9:30am Coffee 10am Welcome Ana Dopico, Director King Juan Carlos I Center Sara Kozameh, Organizer 10:30-12pm Panel 1: Textures of the Everyday Moderator: Ada Ferrer Anasa Hicks, Florida State University Ready to Overcome, Ready to Die: The Emotional Work of Being a Revolutionary Cuban Jesse Horst, Sarah Lawrence College The Revolution, Negotiated from Havana’s Peripheries, 1960-63 William Kelly, Rutgers University “The City Should Mobilize Resources to Remove Insalubrious Neighborhoods”: Resolution No. 122 in Santiago de las Vegas, Cuba Petra Kuivala, University of Helsinki Histories of Lived Religion in the Cuban Revolution 12pm Lunch 1:30-3pm Panel 2: Rethinking the Cuban Revolution in the Latin American Context Moderator: Alejandro Velasco Renata Keller, University of Nevada- Reno Decentering the History of the Cuban Missile Crisis James Hershberg, George Washington University Brazil and the Cuban Revolution: The End of the Affair, 1964 Blanca Mar Leon Rosabál, El Colegio de México Revolutionary Diplomacy and the Third World: Historicizing the Tricontinental Conference from the Cuban Archives. 3:00-4:30 pm Panel 3: Transnational Solidarities and Collaboration Moderator: Barbara Weinstein Daniel Fernandez-Guevara, University of Florida From Unity to Unanimity: Spanish Republican Exiles, Solidarity and the Cuban Revolution, 1959-1963 -

Congratulations to All of the Winners & Finalists of the 2013 USA Best

Congratulations to all of the Winners & Finalists of The 2013 USA Best Book Awards! Categories are listed alphabetically. All finalists are of equal merit. Animals/Pets: General Winner Chasing Doctor Dolittle: Learning the Language of Animals by Con Slobodchikoff, PhD St. Martin's Press 978-0-312-61179-8 Finalist How to Change the World in 30 Seconds: A Web Warrior's Guide to Animal Advocacy Online by C.A. Wulff Barking Planet Productions 978-0978692889 Finalist Pee Where You Want: Man's Best Friend Talks Back! by Karen H. Thompson The Dottin Publishing Group 978-0-9847853-0-8 Animals/Pets: Narrative Non-Fiction Winner M.E. And My Shadow: Wisdom From A Fourlegged Master by Mary Ellen Weiland Shadow Press 978-0-9837443-1-3 Finalist Lessons from Rocky & His Friends: Pawprints on the Heart by Bradford P. Miller LFR Publishing 978-1-4793-5231-9 Anthologies: Non-Fiction Winner No Lumps, Thank You. A Bra Anthologie. Special Edition: Uplifting Stories of Breast Cancer Survival by Meg Spielman Peldo and Kim Wagner Schiffer Publishing 978-0-7643-4288-2 Finalist Essays for my Father: A Legacy of Passion, Politics, and Patriotism in Small-Town America by Richard Muti Richard Muti 978-0-9891482-0-7 Art: General Winner Flight of the Mind, Marcus C. Thomas, A Painter's Journey Through Paralysis by Leslee N. Johnson Lydia Inglett Publishing/Starbooks.biz 978-1-938417-04-7 Art: Instructional/How-To Winner Out There: Design, Art, Travel, Shopping by Maria Gabriela Brito Pointed Leaf Press 978-1938461033 Autobiography/Memoirs Winner IMPOSSIBLE ODDS: The -

Diálogo De La Lengua. Blanca Berasategui Y Jorge Edwards Sobre

w Wl^' Blanca Berasategui nació en Vitoria y Jorge Edwards nació en Santiago de Chile estudió la carrera de Periodismo en y está considerado uno de los grandes Madrid. Ha ejercido gran parte de su escritores en lengua española. Fue Premio vida profesional en la sección de cultura Nacional de Literatura en 1994 y Premio del diario español ABC donde, a partir Miguel de Cervantes en 1999. Estudio de 1980, fue responsable de sus páginas derecho y filosofía y fiíe miembro del literarias. En 1991 creó ABC Cultural, Servicio Exterior chileno desde 1958 hasta publicación que recibió bajo su direc el golpe de Estado de 11973. Es autor de ción numerosos galardones. Blanca cuentos, novelas, ensayos, memorias y ha Berasategui ha trabajado también en sido profesor visitante en diversas universi espacios culturales de radio y televisión, dades europeas y norteamericanas. Su ha dirigido durante dos años la revista de principales novelas son El peso de la noche. pensamiento Cuenta y Razón y es autora Los convidados de piedra. El museo de cera, del libro Gente de palabra. Ha obtenido El anfitrión. La mujer imaginaria. El origen el premio de periodismo Luca de Tena y, del mundo. El Sueño de la Historia, la polé en 2004, el Javier Bueno al mejor perio mica Persona non grata, sobre Cuba, Adiós dismo especializado, que concede la poeta., una evocación de Neruda, que Asociación de la Prensa de Madrid. mereció el premio Comillas, y El inútil de Desde 1999 dirige la revista El Cultural. la familia, de reciente aparición. Durante que aparece todos los jueves en el perió la dictadura de Pinochet fue presidente del dico español El Mundo.