Cultivation Notes No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Field Release of the Leaf-Feeding Moth, Hypena Opulenta (Christoph)

United States Department of Field release of the leaf-feeding Agriculture moth, Hypena opulenta Marketing and Regulatory (Christoph) (Lepidoptera: Programs Noctuidae), for classical Animal and Plant Health Inspection biological control of swallow- Service worts, Vincetoxicum nigrum (L.) Moench and V. rossicum (Kleopow) Barbarich (Gentianales: Apocynaceae), in the contiguous United States. Final Environmental Assessment, August 2017 Field release of the leaf-feeding moth, Hypena opulenta (Christoph) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), for classical biological control of swallow-worts, Vincetoxicum nigrum (L.) Moench and V. rossicum (Kleopow) Barbarich (Gentianales: Apocynaceae), in the contiguous United States. Final Environmental Assessment, August 2017 Agency Contact: Colin D. Stewart, Assistant Director Pests, Pathogens, and Biocontrol Permits Plant Protection and Quarantine Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service U.S. Department of Agriculture 4700 River Rd., Unit 133 Riverdale, MD 20737 Non-Discrimination Policy The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination against its customers, employees, and applicants for employment on the bases of race, color, national origin, age, disability, sex, gender identity, religion, reprisal, and where applicable, political beliefs, marital status, familial or parental status, sexual orientation, or all or part of an individual's income is derived from any public assistance program, or protected genetic information in employment or in any program or activity conducted or funded by the Department. (Not all prohibited bases will apply to all programs and/or employment activities.) To File an Employment Complaint If you wish to file an employment complaint, you must contact your agency's EEO Counselor (PDF) within 45 days of the date of the alleged discriminatory act, event, or in the case of a personnel action. -

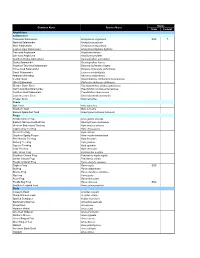

St. Joseph Bay Native Species List

Status Common Name Species Name State Federal Amphibians Salamanders Flatwoods Salamander Ambystoma cingulatum SSC T Marbled Salamander Ambystoma opacum Mole Salamander Ambystoma talpoideum Eastern Tiger Salamander Ambystoma tigrinum tigrinum Two-toed Amphiuma Amphiuma means One-toed Amphiuma Amphiuma pholeter Southern Dusky Salamander Desmognathus auriculatus Dusky Salamander Desmognathus fuscus Southern Two-lined Salamander Eurycea bislineata cirrigera Three-lined Salamander Eurycea longicauda guttolineata Dwarf Salamander Eurycea quadridigitata Alabama Waterdog Necturus alabamensis Central Newt Notophthalmus viridescens louisianensis Slimy Salamander Plethodon glutinosus glutinosus Slender Dwarf Siren Pseudobranchus striatus spheniscus Gulf Coast Mud Salamander Pseudotriton montanus flavissimus Southern Red Salamander Pseudotriton ruber vioscai Eastern Lesser Siren Siren intermedia intermedia Greater Siren Siren lacertina Toads Oak Toad Bufo quercicus Southern Toad Bufo terrestris Eastern Spadefoot Toad Scaphiopus holbrooki holbrooki Frogs Florida Cricket Frog Acris gryllus dorsalis Eastern Narrow-mouthed Frog Gastrophryne carolinensis Western Bird-voiced Treefrog Hyla avivoca avivoca Cope's Gray Treefrog Hyla chrysoscelis Green Treefrog Hyla cinerea Southern Spring Peeper Hyla crucifer bartramiana Pine Woods Treefrog Hyla femoralis Barking Treefrog Hyla gratiosa Squirrel Treefrog Hyla squirella Gray Treefrog Hyla versicolor Little Grass Frog Limnaoedus ocularis Southern Chorus Frog Pseudacris nigrita nigrita Ornate Chorus Frog Pseudacris -

Buttonbush, Cephalanthus Occidentalis

Buttonbush, Cephalanthus occidentalis Buttonbush is a deciduous, multi-stemmed, loose shrub or small tree in the coffee family (Rubiaceae). Generally reaching no more than 12 feet in height, the plant is frequently wider than it is tall. It is native to North America from Nova Scotia and Ontario south to Mexico. It is found in the Florida Everglades. A key characteristic of the Buttonbush is its flower heads which consist of fragrant, tiny, tubular, white flowers compacted into 1-inch diameter spheres. Each flower has a projecting style which gives the flower head a pincushion-like appearance. The long- lasting blooms (June – August) give way to hard, spherical clusters of nutlets that resemble old-time dress buttons; hence its common name. The fruit matures in fall and can stay on the plant through winter, providing interest for the garden and food for wildlife. The beautiful dark green, glossy foliage is another ornamental feature of Buttonbush. The leaves, which emerge late in spring, are opposite or in whorls of three, ovate in shape, 2-6 inches long, 1-3 inches wide, with a smooth edge and short petiole. The leaves turn yellow- green in the fall. Other identifying features of Buttonbush are prominent lenticels on coarse stems, absent terminal buds, and pith that is solid and light brown. Buttonbush occurs as a non-dominant midstory species in mixed riparian forests, pond or stream margins, and swamps. They prefer moist, humusy soils and full to partial sunlight. Buttonbush in the wild is an indicator of an area’s wetland status. The plant will tolerate water depths up to three feet and long durations of flooding. -

Button Bush Cephalanthus Occidentalis L

W&M ScholarWorks Reports 11-1-1994 Button Bush Cephalanthus occidentalis L. Gene Silberhorn Virginia Institute of Marine Science Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/reports Part of the Plant Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Silberhorn, G. (1994) Button Bush Cephalanthus occidentalis L.. Wetland Flora Technical Reports, Wetlands Program, Virginia Institute of Marine Science. Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William and Mary. http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/m2-9xjm-rh51 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reports by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wetlands Technical Report Program Wetland Flora No. 94-10 / November 1994 Gene Silberhorn Button Bush Cephalanthus occidentalis L. Growth Habit and Diagnostic Characteristics Habitat Button bush is a broad-leaved, deciduous shrub that Button bush may occupy several different types of grows up to 2 meters tall with an open spreading wetland habitats, including tidal and nontidal canopy. The simple, smooth marginate leaves are marshes, scrub/shrub and forested wetlands, and the usually oppositely arranged throughout the lower margins of lakes, ponds, ditches and streams. In branches, and are typically whorled (3 or 4 leaves at a bottomland, hardwood forests dominated by tupelo node) just below the terminal borne fruit or flowering (Nyssa aquatica) and bald cypress, Cephalanthus heads. Leaf petioles are often red during the peak occidentalis is often associated with other hydrophytic flowering period when the white globose heads shrubs such as swamp rose (Rosa palustris) and alder develop in July and August. -

Sabal Nov 2019

The Sabal November 2019 Volume 36, number 8 In this issue: November program p1. Native Plant Project (NPP) Board of Directors Species for almost-instant gratification p2 Fall & Winter Nectar & Pollen p3 President: Ken King Winter Fruits p4 Vice Pres: Jann Miller Secretary: Angela Rojas Coma p5 Treasurer: Bert Wessling Arroyo Bank Blooms, Sapindaceae Vines p6 LRGV Native Plant Sources & Landscapers, Drew Bennie NPP Sponsors, Upcoming Meetings p7 Raziel Flores Membership Application (cover) p8 Carol Goolsby Eleanor Mosimann Plant species page #s in the Sabal refer to: Christopher Muñoz “Plants of Deep South Texas” (PDST). Rachel Nagy Ben Nibert Editor: Editorial Advisory Board: Joe Lee Rubio Christina Mild Mike Heep, Jan Dauphin Kathy Sheldon Ann Treece Vacek <[email protected]> Ken King, Betty Perez Submissions of relevant Eleanor Mosimann NPP Advisory Board articles and/or photos Dr. Alfred Richardson Mike Heep are welcomed. Ann Vacek Benito Trevino NPP meeting topic/speaker: “Soil 101” by Mike Heep Tues., November 26th, at 7:30pm A talk by native plant nurseryman Mike Heep is always a treat. This month he’s agreed to talk with us about soil. We’re losing topsoil around the world at an alarming rate, paving it over, bulldozing it away and blowing it to who knows where. Mike lends his years of teaching experience at UT-Edinburg (now UTRVG) to each of his presentations. He has studied our soils and native plants for most of his life. Mike Heep is first and foremost, a dad. Thanks to Ciara Heep for his photo! The meeting is at: Valley Nature Center, 301 S Border, (Gibson Park), Weslaco. -

Diversity and Evolution of Asterids

Diversity and Evolution of Asterids . gentians, milkweeds, and potatoes . Core Asterids • two well supported lineages of the ‘true’ or core asterids ‘ ’ lamiids • lamiid or Asterid I group • ‘campanulid’ or Asterid II group • appear to have the typical fused corolla derived independently and via two different floral developmental pathways campanulids lamiid campanulid Core Asterids • two well supported lineages of the ‘true’ or core asterids lamiids = NOT fused corolla tube • Asterids primitively NOT fused corolla at maturity campanulids • 2 separate origins of fused petals in “core” Asterids (plus several times in Ericales) Early vs. Late Sympetaly euasterids II - campanulids euasterids I - lamiids Calendula, Asteraceae early also in Cornaceae of Anchusa, Boraginaceae late ”basal asterids” Gentianales • order within ‘lamiid’ or Asterid I group • 5 families and nearly 17,000 species dominated by Rubiaceae (coffee) and Apocynaceae lamiids (milkweed) • iridoids, opposite leaves, contorted corolla Rubiaceae Apocynaceae campanulids Gentianales corolla aestivation *Gentianaceae - gentians Cosmopolitan family of 87 genera and nearly 1700 species. Herbs to small trees (in the tropics) or mycotrophs. Gentiana Symbolanthus Voyria *Gentianaceae - gentians • opposite leaves • flowers right contorted • glabrous - no hairs! Gentiana Gentianopsis Blackstonia Gentiana *Gentianaceae - gentians CA (4-5) CO (4-5) A 4-5 G (2) • flowers 4 or 5 merous Gentiana • pistil superior of 2 carpels • parietal placentation; fruit capsular *Gentianaceae - gentians Gentiana -

Plant Profiles: HORT 2241 Landscape Plants I Botanical Name

Plant Profiles: HORT 2241 Landscape Plants I Botanical Name: Cephalanthus occidentalis Common Name: buttonbush Family Name: Rubiaceae – madder family General Description: Known primarily for its unique pincushion-like flowers, Cephalanthus occidentalis is native to the Chicago area and eastern United States where it grows in sunny, wetland habitats. The flowers attract bees and butterflies and the unusual button-like fruits provide a food source for many species of birds. It can grow as a small tree or large shrub, has glossy green leaves, and unique flowers that bloom throughout the summer. Cephalanthus occidentalis is an overlooked ornamental plant that merits more use in moist to wet landscape conditions. Zone: 3-11 Resources Consulted: Dirr, Michael A. Manual of Woody Landscape Plants: Their Identification, Ornamental Characteristics, Culture, Propagation and Uses. Champaign: Stipes, 2009. Print. "The PLANTS Database." USDA, NRCS. National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA, 2014. Web. 23 Mar. 2014. Swink, Floyd, and Gerould Wilhelm. Plants of the Chicago Region. Indianapolis: Indiana Academy of Science, 1994. Print. Creator: Julia Fitzpatrick-Cooper, Professor, College of DuPage Creation Date: 2014 Keywords/Tags: Cephalanthus occidentalis, buttonbush, small tree, large shrub, flowering shrub, deciduous, native Whole plant/Habit: Description: Buttonbush is typically a rounded, irregular shrub that can grow up to 8 foot in the landscape and larger in its native habitat. Image Source: Karren Wcisel, TreeTopics.com Image Date: July 18, 2009 Image File Name: buttonbush_3723.png Flower: Description: Flowers consist of clusters of creamy white flowers in a spherical head often referred to as a pincushion. The beauty of this plant is its long bloom time. -

The Rubiaceae of Ohio

THE RUBIACEAE OF OHIO EDWARD J. P. HAUSER2 Department of Biological Sciences, Kent State University, Kent, Ohio Eight genera and twenty-seven species, of which six are rare in their distribu- tion, are recognized in this study as constituting a part of Ohio's flora, Galium, represented by fifteen species, is the largest genus. Five other genera, Asperula, Cephalanthus, Mitchella, Sherardia, and Spermacoce, consist of a single species. Asperula odorata L., Diodia virginiana L., and Galium palustre L., are new reports for the state. Typically members of the Rubiaceae in Ohio are herbs with the exception of Cephalanthus occidentalis L., a woody shrub, and Mitchella repens L., an evergreen, trailing vine. In this paper data pertinent to the range, habitat, and distribution of Ohio's species of the Rubiaceae are given. The information was compiled from my examination of approximately 2000 herbarium specimens obtained from seven herbaria located within the state, those of Kent State University, Miami Uni- versity, Oberlin College, The Ohio State University, Ohio Wesleyan University, and University of Cincinnati. Limited collecting and observations in the field during the summers of 1959 through 1962 supplemented herbarium work. In the systematic treatment, dichotomous keys are constructed to the genera and species occurring in Ohio. Following the species name, colloquial names of frequent usage and synonyms as indicated in current floristic manuals are listed. A general statement of the habitat as compiled from labels on herbarium specimens and personal observations is given for each species, as well as a statement of its frequency of occurrence and range in Ohio. An indication of the flowering time follows this information. -

FERNS and FERN ALLIES Dittmer, H.J., E.F

FERNS AND FERN ALLIES Dittmer, H.J., E.F. Castetter, & O.M. Clark. 1954. The ferns and fern allies of New Mexico. Univ. New Mexico Publ. Biol. No. 6. Family ASPLENIACEAE [1/5/5] Asplenium spleenwort Bennert, W. & G. Fischer. 1993. Biosystematics and evolution of the Asplenium trichomanes complex. Webbia 48:743-760. Wagner, W.H. Jr., R.C. Moran, C.R. Werth. 1993. Aspleniaceae, pp. 228-245. IN: Flora of North America, vol.2. Oxford Univ. Press. palmeri Maxon [M&H; Wagner & Moran 1993] Palmer’s spleenwort platyneuron (Linnaeus) Britton, Sterns, & Poggenburg [M&H; Wagner & Moran 1993] ebony spleenwort resiliens Kunze [M&H; W&S; Wagner & Moran 1993] black-stem spleenwort septentrionale (Linnaeus) Hoffmann [M&H; W&S; Wagner & Moran 1993] forked spleenwort trichomanes Linnaeus [Bennert & Fischer 1993; M&H; W&S; Wagner & Moran 1993] maidenhair spleenwort Family AZOLLACEAE [1/1/1] Azolla mosquito-fern Lumpkin, T.A. 1993. Azollaceae, pp. 338-342. IN: Flora of North America, vol. 2. Oxford Univ. Press. caroliniana Willdenow : Reports in W&S apparently belong to Azolla mexicana Presl, though Azolla caroliniana is known adjacent to NM near the Texas State line [Lumpkin 1993]. mexicana Schlechtendal & Chamisso ex K. Presl [Lumpkin 1993; M&H] Mexican mosquito-fern Family DENNSTAEDTIACEAE [1/1/1] Pteridium bracken-fern Jacobs, C.A. & J.H. Peck. Pteridium, pp. 201-203. IN: Flora of North America, vol. 2. Oxford Univ. Press. aquilinum (Linnaeus) Kuhn var. pubescens Underwood [Jacobs & Peck 1993; M&H; W&S] bracken-fern Family DRYOPTERIDACEAE [6/13/13] Athyrium lady-fern Kato, M. 1993. Athyrium, pp. -

Native Pond and Wetland Plants May Be Available from Nurseries in the Lower Rio Grande Valley

SCIENTIFIC NAMES OF SPECIES IN THIS BOOK Marginals Bacopa monnieri Cephalanthus salicifolius Cyperus articulatus Echinodorus rostratus Eleocharis obtusa Ludwigia peploides Marsilea macropoda Rhyncospora colorata Sagittaria longiloba Scirpus validus Trichocoronis wrightii Typha domingensis Vigna luteola Emergent Areas or Bog Borrichia frutescens Commelina elegans & C. erecta Coreopsis tinctoria Eustoma exaltatum Helenium microcephalum Heliotropium curassavicum Heteranthera liebmannii Pluchea sp. Polygonum pensylvanicum Solidago sempervirens Sisyrinchium angustifolium & S. biforme Teucrium canadense & T. cubense Deep Water Nelumbo lutea Nymphaea elegans Nymphaea mexicana This handbook is printed with soybean ink on recycled paper in 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction . 2 Selecting Plants . .3 Planting Wetland Plants . .4 Pruning Bog Plants . .5 Pruning Pond Plants . .5 Plant Communities of the Lower Rio Grande Valley . .5 Marginals Arrowhead . .7 Bulrush, Soft Stem . .20 Burhead . .8 Buttonbush, Mexican . .32 Cattail . .34 Cowpea, Wild . .24 Flatsedge . .17 Primrose-willow, Floating . .29 Hairy Crown, Wright’s . .16 Spikerush . .19 Umbrella Grass, White-topped . .18 Water Clover . .25 Water-hyssop . .33 Emergent Areas or Bogs Bluebell Gentian . .21 Blue-eyed Grass . .22 Day Flower . .10 Germander, Seaside & Small Coast . .23 Golden Wave . .12 Goldenrod, Seaside . .15 Pink Smartweed . .31 Salt Marsh Fleabane . .14 Sea Ox-eye Daisy . .11 Seaside Heliotrope . .9 Sneezeweed . .13 Water Stargrass . .30 Widow’s Tears . .10 Deep Water Water Lily, Blue . .26 Water Lily, Yellow . .27 Water Lotus, Yellow . .28 References and Further Reading . .35 Ordering Information . .36 Acknowledgements . .36 Membership Application . .36 INTRODUCTION An estimated 1,200 native flowering plant species grow in the Lower Rio Grande Valley, Texas. The Native Plant Project has selected a var- ied sampling of the native aquatic pond and wetland plants to be featured in this handbook. -

Cephalanthus Occidentalis, Species Information

Cephalanthus occidentalis Index of Species Information SPECIES: Cephalanthus occidentalis ● Introductory ● Distribution and Occurrence ● Management Considerations ● Botanical and Ecological Characteristics ● Fire Ecology ● Fire Effects ● References Introductory SPECIES: Cephalanthus occidentalis AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION : Snyder, S. A. 1991. Cephalanthus occidentalis. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ [2007, March 7]. ABBREVIATION : CEPOCC SYNONYMS : NO-ENTRY SCS PLANT CODE : CECC2 COMMON NAMES : buttonbush common buttonbush button willow riverbush http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/shrub/cepocc/all.html (1 of 12)3/7/2007 11:37:48 AM Cephalanthus occidentalis buttonball TAXONOMY : The currently accepted scientific name for buttonbush is Cephalanthus occidentalis L. (Rubiaceae) [8]. Recognized varieties are as follows [8,21,28]: C. occidentalis var. pubescens (Raf.) C. occidentalis var. californicus (Benth.) C. occidentalis var. angustifolius (Dippel) LIFE FORM : Tree, Shrub FEDERAL LEGAL STATUS : No special status OTHER STATUS : NO-ENTRY DISTRIBUTION AND OCCURRENCE SPECIES: Cephalanthus occidentalis GENERAL DISTRIBUTION : Buttonbush extends from southern Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Quebec, and Ontario south through southern Florida and west through the eastern half of the Great Plains States [8,16]. Scattered populations exist in New Mexico, Arizona, and -

The Family Rubiaceae in Southern Assam with Special Reference to Endemic and Rediscovered Plant Taxa

Journal of Threatened Taxa | www.threatenedtaxa.org | 26 April 2014 | 6(4): 5649–5659 The family Rubiaceae in southern Assam with special reference to endemic and rediscovered plant taxa 1 2 3 4 ISSN H.A. Barbhuiya , B.K. Dutta , A.K. Das & A.K. Baishya Communication Short Online 0974–7907 Print 0974–7893 1 Botanical Survey of India, Eastern Regional Centre, Shillong, Meghalaya 793003, India 2,3 Department of Ecology and Environmental Science, Assam University, Silchar, Assam 788011, India OPEN ACCESS 4 Laban, East Khasi Hills, Shillong, Meghalaya 793009, India 1 [email protected] (corresponding author), 2 [email protected], 3 [email protected], 4 [email protected] Abstract: Analysis of diversity, distribution and endemism of the family Southern Assam (Barak Valley) is located between Rubiaceae for southern Assam has been made. The analyses are based 24008’–25008’N and 92012’–93015’E. The valley covers on field observations in the three districts, viz., Cachar, Hailakandi and 2 Karimganj, as well as data from existing collections and literature. an area of 6,922km and is surrounded by Dima Hasao The present study records 90 taxa recorded from southern Assam, District and Jaintia Hill in the north, the Manipur Hills in four of which are endemic. Chassalia curviflora (Wall.) Thwaites var. ellipsoides Hook. f. and Mussaenda keenanii Hook.f. are rediscovered the east and the Mizoram Hills in the south. To the west after a gap of 140 years. Mussaenda corymbosa Roxb. is reported the plains merge with the Sylhet plains of Bangladesh and for the first time from northeastern India, while Chassalia staintonii the Indian state of Tripura.