Report to the University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis: the 2013 Amendments to South Carolina Code Sections 61-2-180 and 61-4-580 Do Not Substantively Change the Law, Th

ALAN WILSON ATTORNEY GENERAL June 14, 2013 The Honorable Barry J. Barnette Solicitor, Seventh Judicial Circuit 180 Magnolia Street Spa1tanburg, South Carolina 29306 Dear Solicitor Barnette: Attorney General Alan Wilson has referred your letter of March 27, 2013 to the Opinions section for a response. The following is our understanding of your question presented and the opinion of this Office concerning the issue based on that understanding. Issues: Do the 2013 amendments to Sections 61-2-180 and 61-4-580 of the South Carolina Code of Laws mean: I) Any place licensed to serve alcohol may now have bingo, casino nights and poker nights as long as they are for a charitable purpose? 2) May holders of beer and wine permits have game promotions including contests, games of chance, or sweepstakes in which the elements of chance and prize are present and which comply w ith specified requirements contained in subsection 3 [of S.C. Code Section 61-4-580] as long as the game or sweepstakes does not use a '"poker machine?" Law/Analysis: The 2013 amendments to South Carolina Code Sections 61-2-180 and 61-4-580 do not substantively change the law, they merely clarified existing South Carolina law, indicating that Sections 61-2-180 and 61-4-580 are not exceptions or limitations to Section 12-21-2710 (or other sections of the law concerning gambling or games of chance). Our position, which is consistent with the jurisprudence in this State, is that South Carolina law was clear and unambiguous before this amendment. Therefore, the same principles that applied under the law before the amendment apply after it.1 As a background regarding statutory interpretation, the cardinal ru le of statutory construction is to ascertain the intent of the legislature and to accomplish that intent. -

NABCA Daily News Update (3/21/2019) 2

Control State News March 21, 2019 MI: Nearly 130,000 bottles of wine illegally shipped into Michigan MEMBER UPDATE PA: Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board Returns Nearly $2.1 A new benefit has been released for Million in Licensing Fees to Local Communities members. Using your member login, visit https://www.nabca.org/member- VT: Researchers praise Iceland model to reduce teen drug newsletter to view the new Member use Newsletter. The newsletter will include member benefits, surveys, License State News important reminders, upcoming events and so on. MA: In Massachusetts, strict drinking laws are decades in the making As always, if you have any questions concerning your organization’s OK: Bottle Service bill passes House benefits, please contact Dawn Rigaud by calling 703.578.4200. International News NABCA HIGHLIGHTS United Kingdom: Inflation creeps up due to rising price of food, alcohol and tobacco The Public Health Considerations of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (White Paper) Australia: Sydney pubs to stop serving booze in protest at Native American Nations & State Alcohol liquor restrictions Policies: An Analysis (White Paper) Canada: Federal budget suggests Liberals may help 'free Alcohol Technology in the World of Tomorrow the beer,' wine - (White Paper) The Control State Agency Info Sheets. Please Industry News view website for more information. Thirstie raises $7m, joins forces with AB InBev-backed NABCA Survey Database (members only) Drinkworks Upcoming NABCA Meetings Hop Take: Big Beer’s Latest Target Is Health-Conscious, Self- Statistical Data Reports Conscious Women www.NABCA.org Daily News MADD, Nationwide Urge Parents To 'Keep Talking' About Alcohol and Other Drugs During Busy Spring Season March Madness Alcohol Study Shows One Demographic Is Affected the Most “No Unescorted Ladies Will Be Served” NABCA Daily News Update (3/21/2019) 2 CONTROL STATE NEWS MI: Nearly 130,000 bottles of wine illegally shipped into Michigan FOX 47 News March 20, 2019 LANSING, Mich. -

Amongst Friends: the Australian Cult Film Experience Renee Michelle Middlemost University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2013 Amongst friends: the Australian cult film experience Renee Michelle Middlemost University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Middlemost, Renee Michelle, Amongst friends: the Australian cult film experience, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Social Sciences, Media and Communication, University of Wollongong, 2013. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/4063 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Amongst Friends: The Australian Cult Film Experience A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY From UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG By Renee Michelle MIDDLEMOST (B Arts (Honours) School of Social Sciences, Media and Communications Faculty of Law, Humanities and The Arts 2013 1 Certification I, Renee Michelle Middlemost, declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Department of Social Sciences, Media and Communications, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Renee Middlemost December 2013 2 Table of Contents Title 1 Certification 2 Table of Contents 3 List of Special Names or Abbreviations 6 Abstract 7 Acknowledgements 8 Introduction -

Drinking Games Among College Students Emily Schumacher Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep 2012 Awards for Excellence in Student Research & 2012 Awards for Excellence in Student Research Creative Activity - Documents and Creativity 4-11-2012 Drinking Games Among College Students Emily Schumacher Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/lib_awards_2012_docs Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons, and the Place and Environment Commons Recommended Citation Schumacher, Emily, "Drinking Games Among College Students" (2012). 2012 Awards for Excellence in Student Research & Creative Activity - Documents. 3. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/lib_awards_2012_docs/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the 2012 Awards for Excellence in Student Research and Creativity at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2012 Awards for Excellence in Student Research & Creative Activity - Documents by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Emily Schumacher/Drinking Games Among College Students Monday, March 19, 2012 To Whom May Concern: For my research class I was to pick a topic and use Booth Library to garner the resources for my paper. Using EBSCO I was able to use fourteen different refereed journal articles to complete my paper and conduct my study. Without the use of Booth Library this would not have been possible. I chose drinking games as my topic as this is a major issue among college campuses. This project was my pilot study and from this I was able to conduct a fuiiiRB -

KEEPING SCORE on ALCOHOL Keeping Score Is Made Possible by a Grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York

KEEPING SCORE ON ALCOHOL Keeping Score is made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. Drug Strategies is supported by grants from: Abell Foundation Bonderman Family Foundation Carnegie Corporation of New York Annie E. Casey Foundation Edna McConnell Clark Foundation Fannie Mae Foundation William T. Grant Foundation Miriam & Peter Haas Fund Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation Kansas Health Foundation Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr. Foundation John S. & James L. Knight Foundation John D. & Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Open Society Institute Table of Contents Spencer Foundation Introduction. 1 Teenage Alcohol Use . 2 Alcohol and Adults . 8 Pricing, Availability and Advertising . 13 Alcohol and Crime. 17 Alcohol and Health . 22 Treatment for Alcohol Problems . 26 Federal Funding to Reduce Alcohol Abuse . 32 Peter D. Hart Research Associates Poll Conducted for Drug Strategies . 34 Sources . 35 © Copyright 1999 by Drug Strategies INTRODUCTION rug Strategies prepares Keeping Score annually said for alcohol. There has been relatively little Federal D to capture the dimensions of the nation’s drug investment and no comprehensive strategy to address abuse problems and to assess the impact of Federal spend- alcohol-related problems despite their pervasiveness ing to address these problems. This report, supported by and adverse consequences for public health and safety. a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, is One of the Federal government’s largest drug designed to help Americans understand the priorities prevention initiatives—the Office of National Drug reflected in Federal spending so that they can judge for Control Policy’s anti-drug media campaign—is aimed themselves the effectiveness of Federal policies. -

Advertising/Marketing Code and Buying Guidelines

Advertising/Marketing Code and Buying Guidelines Introduction Beer is a legal beverage meant to be consumed responsibly by adults of legal drinking age. Its origins are ancient, and it has held a respected position in nearly every culture and society since the dawn of recorded history. In the United States, beer is a mature product category with broad cultural acceptance and a history of memorable and distinctive advertising that, because of its humor and creativity, has long been a favorite among American adult consumers. Advertising and marketing materials are legitimate efforts by Brewers to inform consumers of the particular styles and attributes of numerous beers and other malt beverages that are available. Brewer advertising and marketing materials also foster competition, persuade adult consumers of beer to try particular brands, and maintain customer loyalty. Brewers should employ the perspective of the reasonable adult consumer of legal drinking age in advertising and marketing their products, and should be guided by the following basic principles, which have long been reflected in the policies of the brewing industry and continue to underlie this Code: • Beer advertising should not suggest directly or indirectly that any of the laws applicable to the sale and consumption of beer should not be complied with. • Brewers should adhere to contemporary standards of good taste applicable to all commercial advertising and consistent with the medium or context in which the advertising appears. • Advertising themes, creative aspects, and placements should reflect the fact that Brewers are responsible corporate citizens. • Brewers strongly oppose abuse or inappropriate consumption of their products. The term “beer” as used in this Code covers all types of malt beverages, including but not limited to, beers and flavored malt beverages, as well as various specialty products containing alcohol such as hard cider. -

Scholastic Takes a Look at the » Defining Beauty by Brigid Sweeney 30 Iattitudes Surrounding Campus Drinking and the Administrative Response

...... COVER PHOTO TABLE OF CONTENTS PHOTO PAGE LESHA NICOLE ZIELINSKI KENNEY v10 " , THE ELEVE TH OF " TOBER " " FYC: Community Composition =m 0 ! TABLE OF CONTENTS" " by Mike Borgia and Jennifer Osterhage " g _ . " i CBL FYC program allows freshmen to reach ". » I Thriving" on Challenge by Kimberly Blackwell 7 r· .outt6 th.~ commu.nity while fulfilling their " i composition requirement. » ! A New Reign by Brendan Ba"rker 26 Sobering Policies 14 "by Matthew Ziegler ' - I COVER: Scholastic takes a look at the » Defining Beauty by Brigid Sweeney 30 Iattitudes surrounding campus drinking and the administrative response. " i » I A Labor of Love by Kathleen Corte 32 \ " .' i Structurally Flawed": "'" 22 From the Editor i Iby Gerard Meskill" " " ".. "" " .' 2 Out of Bounds 29 ND Notebook 4 Week in Distortion 34 :. c"ommentary: A criticallo~k at the current BCS" Campus Watch 21 Calendar 35 " ranking system with suggestions tor improve- Splinters 27 Final Word 36 . ment. i COVER PHOTO TABLE OF CONTENTS PHOTO PAGE LESHA NICOLE ZIELINSKI KENNEY v10 " , THE ELEVE TH OF " TOBER " " FYC: Community Composition =m 0 ! TABLE OF CONTENTS" " by Mike Borgia and Jennifer Osterhage " g _ . " i CBL FYC program allows freshmen to reach ". » I Thriving" on Challenge by Kimberly Blackwell 7 r· .outt6 th.~ commu.nity while fulfilling their " i composition requirement. » ! A New Reign by Brendan Ba"rker 26 Sobering Policies 14 "by Matthew Ziegler ' - I COVER: Scholastic takes a look at the » Defining Beauty by Brigid Sweeney 30 Iattitudes surrounding campus drinking and the administrative response. " i » I A Labor of Love by Kathleen Corte 32 \ " .' i Structurally Flawed": "'" 22 From the Editor i Iby Gerard Meskill" " " ". -

Tang Dynasty Games Magna Faire, AS LIV/2019

Ouyang Yingzhao Tang Dynasty Games Magna Faire, AS LIV/2019 Weiqi (围棋) or Go A game of Strategy Perhaps better known by the name of it’s Japanese deritivie, Go, weiqi (围棋, wéi qí) is a territory control game played with a gridded board and 361 disc-shaped pieces. Unlike western Chess, there are no prescribed, piece-specific directional moves in Go, so that the combination possibilities are almost infinite. In the Tang Dynasty, one’s ability to play Go was a measure of a person’s gentility among the elites (men and women alike), along with calligraphy, music, and painting.1 The earliest reliable record of the game comes from 548 BCE, making it possibly the oldest game that has been continuously played.2 The standard size Go board consists of a grid of 19 by 19 intersections, but variant boards have existed throughout history. The earliest extant board, a fragment from the mausoleum of Emperor Jing (r. 157-141 BCE) is 17 by 17.3 Two more 17 by 17 boards were found in an Eastern Han Dynasty (dates) tomb and official Cao Teng’s tomb (mid-second century). A 15 by 15 board was found in a tomb dated to the late Western Han Dynasty, and similar variants may have survived into the Tang or Liao periods. (dates).4 The earliest 19 by 19 board is made of porcelain and dates to 595, and another is from the early Tang Dynasty, found in the tomb of Ran Rencai (598-652), who was Prefect of Yongzhou.5 To play weiqi, players take turns placing black and white stones on the board’s intersections. -

Drinking Games the Complete Guide Contents

Drinking Games The Complete Guide Contents 1 Overview 1 1.1 Drinking game ............................................. 1 1.1.1 History ............................................ 1 1.1.2 Types ............................................. 2 1.1.3 See also ............................................ 3 1.1.4 References .......................................... 3 1.1.5 Bibliography ......................................... 4 1.1.6 External links ......................................... 4 2 Word games 5 2.1 21 ................................................... 5 2.1.1 Rules ............................................. 5 2.1.2 Additional rules ........................................ 5 2.1.3 Example ............................................ 6 2.1.4 Variations ........................................... 6 2.1.5 See also ............................................ 6 2.2 Fuzzy Duck .............................................. 6 2.2.1 References .......................................... 6 2.3 Ibble Dibble .............................................. 7 2.3.1 Ibble Dibble .......................................... 7 2.3.2 Commercialisation ...................................... 7 2.3.3 References .......................................... 7 2.4 Never have I ever ........................................... 7 2.4.1 Rules ............................................. 7 2.4.2 In popular culture ....................................... 8 2.4.3 See also ............................................ 8 2.4.4 References ......................................... -

Alcohol in Popular Culture

Alcohol in Popular Culture Alcohol in Popular Culture AN ENCYCLOPEDIA Rachel Black, Editor Copyright 2010 by Rachel Black All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Alcohol in popular culture : an encyclopedia / Rachel Black, editor. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978 0 313 38048 8 (hbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978 0 313 38049 5 (ebook) 1. Alcoholic beverages Social aspects United States Encyclopedias. 2. Drinking of alcoholic beverages United States. 3. Alcoholic beverage industry Social aspects United States. I. Black, Rachel, 1975 HV5017.A435 2010 362.2920973 dc22 2010019892 ISBN: 978 0 313 38048 8 EISBN: 978 0 313 38049 5 14 13 12 11 10 1 2 3 4 5 This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook. Visit www.abc clio.com for details. Greenwood An Imprint of ABC CLIO, LLC ABC CLIO, LLC 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116 1911 This book is printed on acid free paper Manufactured in the United States of America For my husband, Doug Cook, who offered me support and encouragement from beginning to end. Contents Preface ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction xiii Timeline xxi List of Entries xxv Guide to Related Topics xxvii The Encyclopedia 1 Selected Bibliography 211 Index 219 About the Editor and Contributors 227 Preface Alcohol production and consumption is a contentious topic in the United States. -

Policy on Drugs and Alcohol 2019 Federal Laws Mandate the Creation and Maintenance of Academic and Working Environments Free from Illicit Drug Use and Alcohol Abuse

Policy on Drugs and Alcohol 2019 Federal laws mandate the creation and maintenance of academic and working environments free from illicit drug use and alcohol abuse. Northwestern University fully supports the objectives of these laws and their companion regulations. The policy statement the University issued in March 1989 to comply with the Drug-Free Workplace Act of 1988 is contained in this document as well as in the student code of conduct. University regulations pertaining to alcohol and drugs are also found in the Faculty and Staff Handbooks. All these remain in effect. This booklet, the North western University Policy on Drugs and Alcohol, provides further amplification of the policy statements in the student and employee handbooks; these handbooks can be found at northwestern.edu/student-conduct/shared-assets/homepage/panel1 /quick-links/images/student-handbook-2019-2020.pdf and northwestern.edu/hr/essentials/policies-procedures/staff-handbook.html. This document is pursuant to the Drug-Free Workplace Act of 1988 and the Drug-Free Schools and Communities Act Amendments of 1989. It is intended to ensure the University’s satisfaction of its legal obligations under that legislation. Morton Schapiro President December 2019 © 2019 Northwestern University. All rights reserved. Produced by Global Marketing and Communications. 2 12-19/AE-VL/2944 Northwestern University policy prohibits the unlawful offered through Counseling and Psychological Services possession, use, or distribution of illicit drugs and alcohol (847-491-2151). Employees are encouraged to contact by its students and employees on University property, the Northwestern Employee Assistance Program (855- as part of any University activities, in vehicles owned or 547-1851). -

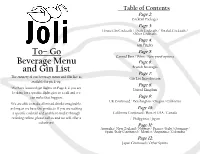

To– Go Beverage Menu and Gin List

Table of Contents Page 2: Cocktail Packages Page 3: House Gin Cocktails / Draft Cocktails / Bottled Cocktails / Other Cocktails Page 4: Gin Flights To– Go Page 5: Canned Beer / Wine / Non-proof options Beverage Menu Page 6: Brunch Beverages and Gin List Page 7: The entirety of our beverage menu and Gin list is Gin List Introduction available for pick-up. Page 8: We have featured gin flights on Page 4; if you are United Kingdom looking for a specific flight give us a call and we can make that happen. Page 9: UK Continued / Washington / Oregon / California We are able to make all mixed drinks imaginable, as long as we have the products. If you are seeking Page 10: a specific cocktail and unable to find it through California Continued / Rest of USA / Canada ordering online, please call us and we will offer a / Philippines / Japan substitute! Page 11: Australia/ New Zealand / Norway / France / Italy / Germany / Spain /Italy Continued / Mexico / Argentina / Colombia Page 12: Japan Continued / Other Spirits Gin Cocktail Packages Your favorite movie is Cocktail; you're in–the-know on the mixology scene; you haven’t had a store bought mix in your fridge since the early 2000’s; it’s finally your time to show your friends and family your shaker skills, fulfill your destiny, and be the star behind the bar! (Alright we’ll provide the ingredients and recipes, BUT you're doing everything else…) Mule it Over $60 16 drinks- $3.75/drink Bellringer London Dry Gin*, ginger-cardamom syrup, lime juice, so- da water, 2 whole limes *upgrade to Geranium London Gin + $20 Build Your Own Negroni Living like ’75 $60 17 drinks- $3..5-$6/drink 16 drinks-$3.75/drink Temple ‘Constant Reader’ Gin, rosemary or lavender syrup, lemon, 1/2 Sweet Vermouth, 1/2 Campari, 1 or- sparkling wine *upgrade to Bainbridge Doug-Fir Gin +$15 ange.