Download Thepdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sean Callery

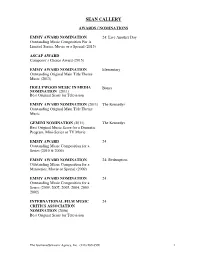

SEAN CALLERY AWARDS / NOMINATIONS EMMY AWARD NOMINATION 24: Live Another Day Outstanding Music Composition For A Limited Series, Movie or a Special (2015) ASCAP AWARD Composer’s Choice Award (2015) EMMY AWARD NOMINATION Elementary Outstanding Original Main Title Theme Music (2013) HOLLYWOOD MUSIC IN MEDIA Bones NOMINATION (2011) Best Original Score for Television EMMY AWARD NOMINATION (2011) The Kennedys Outstanding Original Main Title Theme Music GEMINI NOMINATION (2011) The Kennedys Best Original Music Score for a Dramatic Program, Mini-Series or TV Movie EMMY AWARD 24 Outstanding Music Composition for a Series (2010 & 2006) EMMY AWARD NOMINATION 24: Redemption Outstanding Music Composition for a Miniseries, Movie or Special (2009) EMMY AWARD NOMINATION 24 Outstanding Music Composition for a Series (2009, 2007, 2005, 2004, 2003, 2002) INTERNATIONAL FILM MUSIC 24 CRITICS ASSOCIATION NOMINATION (2006) Best Original Score for Television The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 SEAN CALLERY TELEVISION SERIES JESSICA JONES (series) Melissa Rosenberg, Jeph Loeb, exec. prods. ABC / Marvel Entertainment / Tall Girls Melissa Rosenberg, showrunner BONES (series) Barry Josephson, Hart Hanson, Stephen Nathan, Fox / 20 th Century Fox Steve Bees, exec. prods. HOMELAND (pilot & series) Alex Gansa, Howard Gordon, Avi Nir, Gideon Showtime / Fox 21 Raff, Ran Telem, exec. prods. ELEMENTARY (pilot & series) Carl Beverly, Robert Doherty, Sarah Timberman, CBS / Timberman / Beverly Studios Craig Sweeny, exec. prods. MINORITY REPORT (pilot & series) Kevin Falls, Max Borenstein, Darryl Frank, 20 th Century Fox Television / Fox Justin Falvey, exec. prods. Kevin Falls, showrunner MEDIUM (series) Glenn Gordon Caron, Rene Echevarria, Kelsey Paramount TV /CBS Grammer, Ronald Schwary, exec. prods. 24: LIVE ANOTHER DAY (event-series) Kiefer Sutherland, Howard Gordon, Brian 20 TH Century Fox Grazer, Jon Cassar, Evan Katz, Robert Cochran, David Fury, exec. -

Intellectual Property and Entertainment Law Ledger

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AND ENTERTAINMENT LAW LEDGER VOLUME 1 WINTER 2009 NUMBER 1 MIXED SIGNALS: TAKEDOWN BUT DON’T FILTER? A CASE FOR CONSTRUCTIVE AUTHORIZATION * VICTORIA ELMAN AND CINDY ABRAMSON Scribd, a social publishing website, is being sued for copyright infringement for allowing the uploading of infringing works, and also for using the works themselves to filter for copyrighted work upon receipt of a takedown notice. While Scribd has a possible fair use defense, given the transformative function of the filtering use, Victoria Elman and Cindy Abramson argue that such filtration systems ought not to constitute infringement, as long as the sole purpose is to prevent infringement. American author Elaine Scott has recently filed suit against Scribd, alleging that the social publishing website “shamelessly profits” by encouraging Internet users to illegally share copyrighted books online.1 Scribd enables users to upload a variety of written works much like YouTube enables the uploading of video * Victoria Elman received a B.A. from Columbia University and a J.D. from Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law in 2009 where she was a Notes Editor of the Cardozo Law Review. She will be joining Goodwin Procter this January as an associate in the New York office. Cindy Abramson is an associate in the Litigation Department in the New York office of Morrison & Foerster LLP. She recieved her J.D. from the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law in 2009 where she completed concentrations in Intellectual Property and Litigation and was Senior Notes Editor of the Cardozo Arts & Entertainment Law Journal. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of Morrison & Foerster, LLP. -

Uila Supported Apps

Uila Supported Applications and Protocols updated Oct 2020 Application/Protocol Name Full Description 01net.com 01net website, a French high-tech news site. 050 plus is a Japanese embedded smartphone application dedicated to 050 plus audio-conferencing. 0zz0.com 0zz0 is an online solution to store, send and share files 10050.net China Railcom group web portal. This protocol plug-in classifies the http traffic to the host 10086.cn. It also 10086.cn classifies the ssl traffic to the Common Name 10086.cn. 104.com Web site dedicated to job research. 1111.com.tw Website dedicated to job research in Taiwan. 114la.com Chinese web portal operated by YLMF Computer Technology Co. Chinese cloud storing system of the 115 website. It is operated by YLMF 115.com Computer Technology Co. 118114.cn Chinese booking and reservation portal. 11st.co.kr Korean shopping website 11st. It is operated by SK Planet Co. 1337x.org Bittorrent tracker search engine 139mail 139mail is a chinese webmail powered by China Mobile. 15min.lt Lithuanian news portal Chinese web portal 163. It is operated by NetEase, a company which 163.com pioneered the development of Internet in China. 17173.com Website distributing Chinese games. 17u.com Chinese online travel booking website. 20 minutes is a free, daily newspaper available in France, Spain and 20minutes Switzerland. This plugin classifies websites. 24h.com.vn Vietnamese news portal 24ora.com Aruban news portal 24sata.hr Croatian news portal 24SevenOffice 24SevenOffice is a web-based Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. 24ur.com Slovenian news portal 2ch.net Japanese adult videos web site 2Shared 2shared is an online space for sharing and storage. -

Representations and Discourse of Torture in Post 9/11 Television: an Ideological Critique of 24 and Battlestar Galactica

REPRESENTATIONS AND DISCOURSE OF TORTURE IN POST 9/11 TELEVISION: AN IDEOLOGICAL CRITIQUE OF 24 AND BATTLSTAR GALACTICA Michael J. Lewis A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2008 Committee: Jeffrey Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin ii ABSTRACT Jeffrey Brown Advisor Through their representations of torture, 24 and Battlestar Galactica build on a wider political discourse. Although 24 began production on its first season several months before the terrorist attacks, the show has become a contested space where opinions about the war on terror and related political and military adventures are played out. The producers of Battlestar Galactica similarly use the space of television to raise questions and problematize issues of war. Together, these two television shows reference a long history of discussion of what role torture should play not just in times of war but also in a liberal democracy. This project seeks to understand the multiple ways that ideological discourses have played themselves out through representations of torture in these television programs. This project begins with a critique of the popular discourse of torture as it portrayed in the popular news media. Using an ideological critique and theories of televisual realism, I argue that complex representations of torture work to both challenge and reify dominant and hegemonic ideas about what torture is and what it does. This project also leverages post-structural analysis and critical gender theory as a way of understanding exactly what ideological messages the programs’ producers are trying to articulate. -

Youtube and the Vernacular Rhetorics of Web 2.0

i REMEDIATING DEMOCRACY: YOUTUBE AND THE VERNACULAR RHETORICS OF WEB 2.0 Erin Dietel-McLaughlin A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2010 Committee: Kristine Blair, Advisor Louisa Ha Graduate Faculty Representative Michael Butterworth Lee Nickoson ii ABSTRACT Kristine Blair, Advisor This dissertation examines the extent to which composing practices and rhetorical strategies common to ―Web 2.0‖ arenas may reinvigorate democracy. The project examines several digital composing practices as examples of what Gerard Hauser (1999) and others have dubbed ―vernacular rhetoric,‖ or common modes of communication that may resist or challenge more institutionalized forms of discourse. Using a cultural studies approach, this dissertation focuses on the popular video-sharing site, YouTube, and attempts to theorize several vernacular composing practices. First, this dissertation discusses the rhetorical trope of irreverence, with particular attention to the ways in which irreverent strategies such as new media parody transcend more traditional modes of public discourse. Second, this dissertation discusses three approaches to video remix (collection, Detournement, and mashing) as political strategies facilitated by Web 2.0 technologies, with particular attention to the ways in which these strategies challenge the construct of authorship and the power relationships inherent in that construct. This dissertation then considers the extent to which sites like YouTube remediate traditional rhetorical modes by focusing on the genre of epideictic rhetoric and the ways in which sites like YouTube encourage epideictic practice. Finally, in light of what these discussions reveal in terms of rhetorical practice and democracy in Web 2.0 arenas, this dissertation offers a concluding discussion of what our ―Web 2.0 world‖ might mean for composition studies in terms of theory, practice, and the teaching of writing. -

The Effects of Digital Music Distribution" (2012)

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School Spring 4-5-2012 The ffecE ts of Digital Music Distribution Rama A. Dechsakda [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp The er search paper was a study of how digital music distribution has affected the music industry by researching different views and aspects. I believe this topic was vital to research because it give us insight on were the music industry is headed in the future. Two main research questions proposed were; “How is digital music distribution affecting the music industry?” and “In what way does the piracy industry affect the digital music industry?” The methodology used for this research was performing case studies, researching prospective and retrospective data, and analyzing sales figures and graphs. Case studies were performed on one independent artist and two major artists whom changed the digital music industry in different ways. Another pair of case studies were performed on an independent label and a major label on how changes of the digital music industry effected their business model and how piracy effected those new business models as well. I analyzed sales figures and graphs of digital music sales and physical sales to show the differences in the formats. I researched prospective data on how consumers adjusted to the digital music advancements and how piracy industry has affected them. Last I concluded all the data found during this research to show that digital music distribution is growing and could possibly be the dominant format for obtaining music, and the battle with piracy will be an ongoing process that will be hard to end anytime soon. -

View Full Article

ARTICLE ADAPTING COPYRIGHT FOR THE MASHUP GENERATION PETER S. MENELL† Growing out of the rap and hip hop genres as well as advances in digital editing tools, music mashups have emerged as a defining genre for post-Napster generations. Yet the uncertain contours of copyright liability as well as prohibitive transaction costs have pushed this genre underground, stunting its development, limiting remix artists’ commercial channels, depriving sampled artists of fair compensation, and further alienating netizens and new artists from the copyright system. In the real world of transaction costs, subjective legal standards, and market power, no solution to the mashup problem will achieve perfection across all dimensions. The appropriate inquiry is whether an allocation mechanism achieves the best overall resolution of the trade-offs among authors’ rights, cumulative creativity, freedom of expression, and overall functioning of the copyright system. By adapting the long-standing cover license for the mashup genre, Congress can support a charismatic new genre while affording fairer compensation to owners of sampled works, engaging the next generations, and channeling disaffected music fans into authorized markets. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 443 I. MUSIC MASHUPS ..................................................................... 446 A. A Personal Journey ..................................................................... 447 B. The Mashup Genre .................................................................... -

Night Ripper Game Free Download Night Ripper Game Free Download

night ripper game free download Night ripper game free download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 66afcb849cee8498 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Night Watch Puppet Combo Download Free. Posted: (8 days ago) May 01, 2020 · Download Minecraft Map. Download : Night Watch How to install Minecraft Maps on Java Edition. Inspired by a Puppet Combo game : NIGHT WATCH Texture Pack and map made by : Trevencraftxxx ( me :D ) Progress: 100% complete: Tags: Horror. Night. Creepy. Puzzle. Challenge Adventure. Nightwatch. 2. Night Watch | Puppet Combo Wiki | Fandom. Posted: (5 days ago) Night Watch is a 2019 horror game developed by Puppet Combo. The game is available for download on Puppet Combo's Patreon1. 1 Summary 1.1 Outcome 1 1.2 Outcome 2 1.3 Outcome 3 2 Trivia 3 Gallery 4 References The game follows a park ranger named Jim who was assigned on watch duty on top of the tower in the middle of the park, where he specifically has to check for fires and guide any … Night Watch is Out! Park Ranger HORROR - Puppet Combo. -

Downloading, Streaming and Digital Lending

Music in the Digital Age: Downloading, Streaming and Digital Lending James Mason, University of Toronto Jared Wiercinski, Concordia University Introduction The ways in which we listen to music, and the places we look to find it, have changed radically in the last thirty years. In 1980, Philips and Sony proposed the Red Book standard for Compact Discs (CDs),1 with a little help from Beethoven.2 Although it was not the first storage medium for digital audio, the introduction of the CD signaled that the world of digital music was about to go mainstream. The technology behind communications devices such as telephones, radios, and personal computers continued to evolve, and before long, the foundation for the Internet was firmly in place. This multifaceted and complex "global system of interconnected computer networks"3 was about to revolutionize the distribution of sound recordings. As Leiner says, "The Internet is at once a world-wide broadcasting capability, a mechanism for information dissemination, and a medium for collaboration and interaction between individuals and their computers without regard for geographic location."4 Only fifteen years after the introduction of the Red Book, music was being distributed over the Internet. RealNetworks' RealAudio Player, for example, was released in April 1995, and was one of the first media players capable of streaming media over the Internet.5 Now, recorded music is more accessible than ever before. We enjoy unprecedented access to music through a variety of means, including both web access and via mobile devices such as smartphones, the iPod touch 1 British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) News, “How the CD Was Developed,” http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/technology/6950933.stm (accessed March 16, 2010). -

The Relationship Between Local Content, Internet Development and Access Prices

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN LOCAL CONTENT, INTERNET DEVELOPMENT AND ACCESS PRICES This research is the result of collaboration in 2011 between the Internet Society (ISOC), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). The first findings of the research were presented at the sixth annual meeting of the Internet Governance Forum (IGF) that was held in Nairobi, Kenya on 27-30 September 2011. The views expressed in this presentation are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of ISOC, the OECD or UNESCO, or their respective membership. FOREWORD This report was prepared by a team from the OECD's Information Economy Unit of the Information, Communications and Consumer Policy Division within the Directorate for Science, Technology and Industry. The contributing authors were Chris Bruegge, Kayoko Ido, Taylor Reynolds, Cristina Serra- Vallejo, Piotr Stryszowski and Rudolf Van Der Berg. The case studies were drafted by Laura Recuero Virto of the OECD Development Centre with editing by Elizabeth Nash and Vanda Legrandgerard. The work benefitted from significant guidance and constructive comments from ISOC and UNESCO. The authors would particularly like to thank Dawit Bekele, Constance Bommelaer, Bill Graham and Michuki Mwangi from ISOC and Jānis Kārkliņš, Boyan Radoykov and Irmgarda Kasinskaite-Buddeberg from UNESCO for their work and guidance on the project. The report relies heavily on data for many of its conclusions and the authors would like to thank Alex Kozak, Betsy Masiello and Derek Slater from Google, Geoff Huston from APNIC, Telegeography (Primetrica, Inc) and Karine Perset from the OECD for data that was used in the report. -

P2P Removal Windows Vista Both

P2P Programs on How to Disable File Sharing Windows Vista on Windows Vista Using file sharing or peer‐to‐peer (P2P) programs to download/share To disable simple file sharing, just follow these steps: copyrighted materials (or just having copyrighted materials in a shared 1. From the Start menu, click Control Panel file on your computer) is a violaon of the UGA Code of Conduct. 2. In the Control Panel, click Network and Internet Organizaons represenng copyrighted industries monitor the UGA 3. Click Network and Sharing Center network and report to UGA when someone on the network has 4. Expand this secon by clicking the buon next to File Sharing inappropriately shared files. 5. Click the circle buon marked Turn Off File Sharing 6. Click Apply for changes to take effect How to remove a P2P Program Disabling file sharing may have an effect on other computer programs Just as you would remove any program from your Windows and does not insure the legality of your media. Be sure to also delete any system, use the Add/Remove Programs window in the Control Types of P2P P2P program from your computer. Panel to remove (uninstall) these programs. Limewire BitTorrent 1. Close and turn off all file sharing programs and their Legal Alternatives for Media Morpheus components 2. Click Start Gnutella There are several legal alternaves for digital music, here are a few: Aresware 3. Open the Control Panel Internet Radio Staons Media Downloading Websites Kazaa Click Control Panel or Pandora iTunes Click Sengs > Control Panel Yahoo! Amazon 4. Click Programs and Features Rhapsody Napster 5. -

Media Pranks: a Three-Act Essay

- Media Pranks: A Three-Act Essay. McLeod, Kembrew https://iro.uiowa.edu/discovery/delivery/01IOWA_INST:ResearchRepository/12675012580002771?l#13675073930002771 McLeod, K. (2011). Media Pranks: A Three-Act Essay. International Journal of Communication, 5, 1725–1736. https://iro.uiowa.edu/discovery/fulldisplay/alma9983557573502771/01IOWA_INST:ResearchRepository Document Version: Published (Version of record) https://iro.uiowa.edu CC BY-NC-ND V4.0 Copyright © 2011 Kembrew McLeod Downloaded on 2021/09/29 04:28:54 -0500 - International Journal of Communication 5 (2011), Feature 1725–1736 1932–8036/2011FEA1725 Media Pranks: A Three-Act Essay KEMBREW McLEOD University of Iowa Times are tough for public universities. Over the past quarter-century, state legislatures have slashed college budgets, and these cuts have only accelerated during a seemingly endless economic meltdown. We have been told to do more with less, make sacrifices, and be self-sufficient—and I couldn’t agree more. Unlike those socialists lining up to mainline milk from the nanny state, many of us favor fiscally sound solutions. We should teach our children well by following dogmatically free-market principles that reject government meddling. My modest proposal is multipronged and forward-thinking. It would hand over all aspects of academic life to private companies, creating a university system that is more efficient, even profitable. In reimagining how higher education can be rebooted, we must ask ourselves, “What would a liberal arts education look like if McDonald’s funded it?” Killing many birds with one lethal stone, we can simultaneously solve the problems of overstuffed budgets, overpaid professors, and—as an added, unexpected bonus—plagiarism.