Seeking Subjectivity Beyond the Objectification Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

59Th Annual Critics Poll

Paul Maria Abbey Lincoln Rudresh Ambrose Schneider Chambers Akinmusire Hall of Fame Poll Winners Paul Motian Craig Taborn Mahanthappa 66 Album Picks £3.50 £3.50 .K. U 59th Annual Critics Poll Critics Annual 59th The Critics’ Pick Critics’ The Artist, Jazz for Album Jazz and Piano UGUST 2011 MORAN Jason DOWNBEAT.COM A DOWNBEAT 59TH ANNUAL CRITICS POLL // ABBEY LINCOLN // PAUL CHAMBERS // JASON MORAN // AMBROSE AKINMUSIRE AU G U S T 2011 AUGUST 2011 VOLUme 78 – NUMBER 8 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Managing Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Assistant Theresa Hill 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point, Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Or- leans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

They Might Be Giants 2018 Live

2018 LIVE 1. THE COMMUNISTS HAVE THE MUSIC 2018 LIVE 2. YOUR RACIST FRIEND 3. ALL TIME WHAT 4. WHICH DESCRIBES HOW YOU’RE FEELING 5. SPY 6. APPLAUSE APPLAUSE APPLAUSE 7. I LIKE FUN 8. WHY DOES THE SUN SHINE? (THE SUN IS A MASS OF INCANDESCENT GAS) 9. A SELF CALLED NOWHERE 10. ISTANBUL (NOT CONSTANTINOPLE) 11. LET’S GET THIS OVER WITH 12. WHISTLING IN THE DARK 13. AUTHENTICITY TRIP 14. ANA NG 15. HEY, MR. DJ, I THOUGHT YOU SAID WE HAD A DEAL 16. HEARING AID 17. MRS. BLUEBEARD ℗ & © 2018 Idlewild Recordings PO Box 176, Palisades, NY 10964 Recorded live around the United States, Canada, the UK, and Europe on tour in 2018 This album could not have been made without the hard work of Scott Bozack (Tour Manager/Front of House Engineer), Jon Carter (Monitor Engineer), Jon Brunette (Guitar Tech), Saul Slezas (Lighting Director), Anna Bartenstein (Merchandise), and Jeff “Fresh” Peterson (Stage Manager) They Might Be Giants are John Linnell keyboards, accordion, contra-alto clarinet, vocals John Flansburgh guitars, vocals Danny Weinkauf bass Dan Miller guitar, keyboards Marty Beller drums Curt Ramm trumpet, trombone, euphonium Engineered and mixed by Scott Bozack A&R Marty Beller Mastered by Kevin Salem Design TS Rogers Cover photo Jon Brunette Interior photos Jon Uleis Management Jamie Lincoln Kitman and Pete Smolin The Hornblow Group USA, Inc. Booking Frank Riley and Dave Rowan High Road Touring Zac Peters DMF Music Publicity Felice Ecker and Sarah Avrin Girlie Action All songs copyright They Might Be Giants, TMBG Music (BMI) except “Istanbul (Not Constantinople)” Jimmy Kennedy and Nat Simon, Warner/Chappell (ASCAP) and “Why Does the Sun Shine (The Sun is a Mass of Incandescent Gas)” Hy Zaret and Lou Singer, Argosy Music Corp. -

JUST ANNOUNCED Susanne Sundfør Monday 21 May 2018 / Barbican Hall / 19:30 Tickets £15 – 20 Plus Booking Fee After a Sold-O

JUST ANNOUNCED Susanne Sundfør Monday 21 May 2018 / Barbican Hall / 19:30 Tickets £15 – 20 plus booking fee After a sold-out Norwegian tour earlier this year, Susanne Sundfør will bring her critically acclaimed Music for People in Trouble production to the Barbican on 21 May 2018. The audio-visual experience and immersive show reflects her recent album in live art form, and has earned rave reviews. This will be the first time it has been performed outside Norway. The opportunity to bring this special concert to the Barbican sadly means cancelling her previously announced appearance at 02 Shepherd’s Bush Empire due to the performance’s production requirements. Refunds for the Shepherd’s Bush Empire date will be available from point of purchase. Original ticket holders will be contacted by e- mail offering the first opportunity to re-book for this show. The classically-trained singer/songwriter/producer's music ranges from folk-song to synth-pop, and she has collaborated with the likes of John Grant, M83 and Röyksopp in the process. Her fifth studio album, also titled Music for People in Trouble (Bella Union) was released in September 2017 to much praise. On sale to previous bookers on Thursday 16 November On sale to Barbican members on Thursday 23 November On general sale on Friday 24 November Produced by the Barbican in association with Communion Find out more Tigran Hamasyan & Nils Petter Molvaer Saturday 2 June 2018 / Barbican Hall / 19:30 Tickets £20 – 35 plus booking fee Tigran Hamasyan returns to London offering a blend of his own solo piano and choral works with the exciting addition of guest trumpeter, Nils Petter Molvaer. -

February 1, 2018

February 1, 2018 Volume 97 Number 20 THE DUQUESNE DUKE www.duqsm.com PROUDLY SERVING OUR CAMPUS SINCE 1925 Pitt junior Making a blanket statement Founder’s running Week for local celebrates state school’s rep seat past RAYMOND ARKE news editor GABRIELLA DIPIETRO staff writer Many students vote and follow The Spiritans saw a community the news, and some wish to be a real in need and founded Duquesne part of the political process. For one University 140 years ago. To honor University of Pittsburgh student, these individuals, Duquesne hosts he’s following through on that wish. a week-long celebration known as Jacob Pavlecic, a 20-year-old Founder’s Week. junior at Pitt majoring in politics Founder’s Week focuses on a and philosophy and with minors different theme each year, and this in finance and French, has an- year is centered around the theme nounced he is running for the of “Be Well in the Spirit” because 30th District in the Pennsylvania wellbeing is considered to be a House of Representatives in the pervasive part of life. Democratic primary. The 30th Ian Edwards, assistant vice District consists of Hampton president for student wellbeing Township, Richland Township, and director of counseling servic- the borough of Fox Chapel and es, emphasized the importance of parts of O’Hara and Shaler Town- overall happiness. ships, according to the Pennsylva- “Wellbeing is the very vehicle nia Department of State. through which one’s sense of Pavlecic credited the idea of run- MEGAN KLINEFELTER/STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER ning for state office to his best friend. -

March 15-21, 2018

MARCH 15-21, 2018 FACEBOOK.COM/WHATZUPFTWAYNE // WWW.WHATZUP.COM ------------------- Feature • Fort Wayne Ballet ----------------- Bringing Magic to Life By Michele DeVinney ably universal. “The characters in Coppélia are more relatable Although a popular ballet, and one which Fort than in some of the fairy tale ballets,” says Gibbons- SPRING Wayne Ballet last performed in 2011, Coppélia isn’t Brown. “It’s a light-hearted look at the struggles of always instantly recognizable to the casual dance fan. relationships and communities.” The story of a toy maker who creates a doll to love as There’s a lot to behold visually as well. his own is perhaps less familiar than fairy tales like “The costumes for Coppélia are always a feast for Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty which have a strong the eyes, and the toymaker’s toy shop in the second SAXOPHONESALE non-dance following of their own. But Coppélia comes act is also beautiful. This isn’t FAO Schwartz. This is from the same mind as perhaps the most famous and the place of a man who wants a child of his own and ubiquitous ballets of all time, The Nutcracker. wants to bring this life-like doll to life. And for awhile E.T.A. Hoffmann has he really believes it. It’s in created a world in Cop- the toy shop that we have pélia that is very similar some of our student danc- UNBELIEVABLE PRICES ON SAXOPHONES! to the Sugar Plum fantasy ers who get to perform as that audiences flock to see the dolls which is a lot of every holiday season, with fun for them.” the mysterious Dr. -

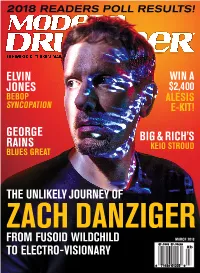

38 ZACH DANZIGER He Freely Breaks Every Rule 26 on TOPIC: PATTY SCHEMEL but One: to Thine Own Self by Stephen Bidwell Be True

2018 READERS POLL RESULTS! THE WORLD’S #1 DRUM MAGAZINE ELVIN WIN A JONES $2,400 BEBOP ALESIS SYNCOPATION E-KIT! GEORGE BIG & RICH’S RAINS KEIO STROUD BLUES GREAT THE UNLIKELY JOURNEY OF ZACH DANZIGER FROM FUSOID WILDCHILD MARCH 2018 TO ELECTRO-VISIONARY 12 Modern Drummer June 2014 83% OF DRUMMERS SAID THEY’D SWITCH TO UV1. OMAR HAKIM ACTUALLY DID.* * MAYBE THAT’S BECAUSE THE NEW EVANS UV1 10mil single-ply drumhead is more versatile and durable than the heads they were playing before, thanks to its patented UV-cured coating. UV1.EVANSDRUMHEADS.COM Congratulations are in order for our Audix endorsers who were recognized by the readers of Modern Drummer this year! Our artist endorsers are a part of the Audix family. We are proud of the contributions they provide through volunteering their time to educate, support, and serve as leaders for the drumming community. TODD SUCHERMAN THOMAS LANG STANTON MOORE Progressive & Recorded Clinician / Educator Clinician / Educator & Performance Educational Product D2D4 D6 ADX51 i5 ©2017 Audix Corporation All Rights Reserved. Audix and audixusa.com all the Audix logos are trademarks of Audix Corporation. 503.682.6933 The Chosen Ones Choose Yamaha It is our privilege to recognize this year’s Readers Poll nominees for excellence in artistry, and we are honored that these outstanding performers choose to play Yamaha. Congratulations from all of us to all of you. CONTENTS Volume 42 • Number 3 CONTENTS Cover and Contents photos by Lloyd Bishop ON THE COVER 38 ZACH DANZIGER He freely breaks every rule 26 ON TOPIC: PATTY SCHEMEL but one: To thine own self by Stephen Bidwell be true. -

Titles Ordered January 26 - February 2, 2018

Titles ordered January 26 - February 2, 2018 Book Adult Fiction Release Date: Bay, Louise. Indigo nights / Louise Bay. http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1567798 Bay, Louise. Parisian nights / Louise Bay. http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1567877 Bay, Louise. Promised nights / Louise Bay. http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1567801 Caine, Rachel, author. Killman Creek / Rachel Caine. http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1567794 12/12/2017 Clipston, Amy, author. Room on the porch swing / Amy Clipston. http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1569575 5/8/2018 Dunn, Sarah, 1969- author. The arrangement : a novel / Sarah Dunn. http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1568009 3/21/2017 Eastman, Dawn, author. Unnatural causes / Dawn Eastman. http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1568013 12/12/2017 Hampton, Brenda Bff's Forever: Best Frenemies Forever Series, Books 1- http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1569316 5/29/2018 3 McCall Smith, Alexander, 1948- author. The good pilot Peter Woodhouse : a novel / http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1569576 4/10/2018 Alexander McCall Smith. Olson, Bob. The magic mala : a story that changes lives / Bob http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1567800 Olson. Rowe, Ruby The terms / Ruby Rowe. http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1567876 Rowe, Ruby. The terms. Part two / Ruby Rowe. http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1567875 Shantae Back to Life: Love After Heartbreak http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1569317 5/29/2018 Snelling, Lauraine A Breath of Hope http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1569572 4/3/2018 Trollope, Joanna An Unsuitable Match http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1569573 5/1/2018 Adult Non-Fiction Release Date: The complete outdoor builder : from arbors to http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1567810 walkways : 150 DIY projects. -

Bowling Green!

November 2011 ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT ARTIST: Christy Long Music: • Ned Hill • Keith Hurt & Paul Hatchett • Local Artists On The World Scene best of bowling green CD Reviews • Recent Releases • Photography • Fashion • Health GARY FORCE HONDA and TOYOTA BEST New Car Dealer BEST Preowned Car Dealer in Bowling Green Thanks for your Vote! Bethany Jewell (270) 782-7904 1901 Russellville Rd. Bowling Green [email protected] © 2009 Allstate Insurance Company allstate.com Top Top TenTen ReasonsReasons forfor beingbeing thethe Best Best ofof BowlingBowling Green:Green: Thank you 10) 4 Convenient Locations Thank you 9) Best selection of products and knowledge for for votingvoting 8) Great customer service and caters to a wide range of clientele Chuck’s Chuck’s thethe 7) Only rewards program to give back to customers Best of BG 6) The only supplier of homebrew Best of BG selection 5) Supplies local wines and products to support our community 4) Proudly supporting WKU and our local communities for over 40 years 3) Best selection of draft beer on tap 2) Rated A+ World Class by Beer Advocate 1) 1) Chuck’sChuck’s DoesDoes itit Better!Better! Open 8 a.m. - 11 p.m. Mon - Sat FOUR LOCATIONS TO SERVE YOU BETTER. Chuck’s Wine & Spirits • 386 Three Springs Road • 270-781-5923 Chuck’s Liquor Outlet • 575 Veterans Memorial Blvd. • 270-846-2626 Chuck Evans Liquor Outlet • 3513 Louisville Road • 270-842-6015 Chuck’s • 1640 B. Scottsville Road • 270-393-7077 Follow us at “Chuck’s Liquor Outlets” on Facebook - Visit us at www.chucksliquoroutlets.com Wine Tastings at all Locations Friday and Saturday from 4 p.m. -

Right Arm Resource Update

RIGHT ARM RESOURCE UPDATE JESSE BARNETT [email protected] (508) 238-5654 www.rightarmresource.com www.facebook.com/rightarmresource 2/21/2018 Danielle Nicole “Cry No More” The title track single from her new album, in stores Friday New at WCBE, WEXT, KDNK, KSUT, KVNF, MSPR, KSMF Early at KTBG, WTMD, KJAC, KBAC, WFIV, WYCE, KDBB, WUTC “Danielle Nicole is Kansas City Royalty...A treasured part of who we are. Cry No More is a career highlight, and the title track her crowning achievement.” -Jon Hart/KTBG Extensive tour dates going on through May Brian Fallon “If Your Prayers Don’t Get To Heaven” The new single from Sleepwalkers, out now New this week: KJAC, WEHM, WCNR, WFIV Early adds at WFUV, WBJB “It’s just Fallon and his microphone, crooning and crowing over these rhythm and blues-focused rave-ups, holding court over an old-school rock revival to match his restless mood.” - The AV Club On tour this spring Available for download from Republic or my Dropbox James Bay “Wild Love” The follow-up to his enormously successful debut Chaos And The Calm Mediabase 37*, BDS Monitored New & Active! New: WAPS, KRVO, KRML, WVOD, KDEC Already on WMMM, KINK, WPYA, WCLZ, KXT, Music Choice, WWCT, KVNV, WCOO, KROK, KPND, KVNA, WFIV US tour: 3/25 Seattle, 3/27 San Francisco, 3/28 Los Angeles, 3/31 Chicago, 4/2 DC, 4/3 Brooklyn, 4/5 Boston, 4/6 Philadelphia Mia Dyson “Fool” The first single from If I Said Only So Far I Take It Back, out now Already on XM Loft, WSGE, WFIV, WTMD, WYCE Out on Single Lock, the album is co-produced by Ben Tanner (Alabama -

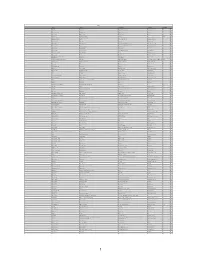

Raw Chart, March 25, 2018 Send 2

Table 1 On Air Off Air Show Name Category DJ Name 8 Phredd Ukulele Jack Ukulele One Man Band Phredderiffic Music New 5 Yo La Tengo For You Too There's a Riot Going On Matador New 4 Guided By Voices See My Field See My Field - Single GBV Inc New 4 Hot Snakes Jericho Sirens Jericho Sirens Sub Pop New 4 Karl Lauber the way she moves live on air Local New 4 The Last Gang Sing for Your Supper Keep Them Counting Fat Wreck Chords New 3 Big Block Singsong Move It Greatest Hits, Vol. 3 Big Block Singsong New 3 Bobs & LoLo blue skies Blue Skies independent New 3 Buck Curran Improvisation 1 Morning Haikus, Afternoon Ragas Obsolete Recordings New 3 Camp Cope anna How to Socialise & Make Friends Run For Cover Records, LLC New 3 Cheap Tissue Feed the Children Cheap Tissue Lolipop Records New 3 Cielito Lindo Cielito Lindo Cielito Lindo s/p New 3 dead meadow Keep Your Head The Nothing They Need Xemu Records New 3 Dean Ween Group The Ritz Carlton rock2 Schnitzel Records New 3 Doctor Noize Exclaim! Punctuate This! Grammaropolis Music New 3 Godspeed You Black Emperor Fam/Famine Luciferian Towers Constellation New 3 Meu Quintal Baiao do já Roda Gigante s/p New 3 nathaniel rateliff & the night sweats Shoe Boot Tearing at the Seams Concord Records, Inc. (UMG Account) 2018 New 3 Steve Weeks Wish You Were Here Wish You Were Here Steve Weeks Music New 3 Tracey Thorn Queen Record Merge Records New 3 U.S. Girls Incidental Boogie In a Poem Unlimited 4AD New 2 Brenda Navarrete Taita Bilongo Mi Mundo Alma Records New 2 Buffalo Tom Roman Cars Quiet and Peace Schoolkids -

Volume Ii. Washington City. D. C., April 14, 1872. Number 6

/ VOLUME II. WASHINGTON CITY. D. C., APRIL 14, 1872. NUMBER 6. For TEX CAPITAL. made my heart achc, and went straight to my desk artistic profu^on of statuary, bronzes, sociables, THE WATCH. and toek out of a pigeon-hole a lot of papers—odes . THE TWISS LIBEL CASE. iujure if believed, and libels which must injure upon your cruelty, Isabel; songs to you; sonnets— lounging chairs, book cases, secretaries, and The reading world is by this time fuuiiliar whether believed or not." BY FRANCES MARIE COLE. wine bouffets, that the roulette table with its the sonnet, a mighty poor one, I'd made the day be- with the above-named case, where an infamous The Saturday Review treating generally of this busy basin and its dancing balls, and the faro Long on the slippery shingles at high tide forehand threw them all Into the grate. Then she scoundrel brought about the ruin of a family— Twlss case says: I watched the coming of your tardy sail— table with its ivory cards glued to the green turned to me again, sighed adieu with mute lips, and a family known to and respected by the most "We arc, as Is well known, an admirable peo- Scanning the world of breakers wild and wide, passed out. I could hear the bottom wire of the poor cloth and its little silver box, and the bac-ca-rat refined circles of England—and then escaped ple ; and, if we have a strong point, it is the Until the sunset Arcs burned low and pale.