1977 National Elections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ncd-Enrolment-Places

2017 National Election Electoral Roll Update Locations National Capital District Electorate: Moresby-South LOCATION ROLL UPDATE PLACE DURATION (Locations in the Ward) (Places in the Ward Locations) (For how long) WARD 1 Badihagwa Lohia Daroa’s Residence 14 Days Tatana 1 Heni Gagoa’s Residence 14 Days Hanuabada 1 Vahoi 1 14 Days Tatana 2 Araira Church Hall 14 Days Hanuabada 2 Vahoi 2 14 Days Baruni 1 Iboko Place 14 Days Baruni 2 Iboko Place 14 Days Hanuabada – Laurabada 1 Kwara Dubuna 1 14 Days Hanuabada – Laurabada 2 Kwara Dubuna 2 14 Days Idubada Idubada 14 Days Hanuabada – Lahara Mission Station 7 14 Days Kanudi Origin Place 14 Days Hanuabada – Lahara Kavari Mission Station 2 14 Days Koukou Settlement David Goroka 14 Days Elevala 1 Abisiri 1 14 Days Elevala 2 Abisiri 2 14 Days Kade Baruni Rev. Ganiga’s Residence 14 Days Borehoho Borehoho 14 Days Gabi Mango Fence – Open Air 14 Days WARD 2 Ela Beach SDA church – Open Air 14 Days Ela Makana Yet to Confirm 14 Days Lawes Road Mobile Team 14 Days Konedobu Aviat Club – Open Air 14 Days Newtown Volley Ball Court 14 Days Vanama Settlement Volley Ball Court 14 Days Paga Hill Town Police Station 14 Days Touaguba Hill Town Police Station 14 Days Town Town Police Station 14 Days Ranuguri Settlement Ranuguri - Open Air 14 Days Segani Settlement Ranuguri - Open Air 14 Days Gini Settlement Residential Area 14 Days Vainakomo Residential Area 14 Days Kaevaga Residential Area 14 Days Paga Settlement Moved to 6mile/Gerehu 14 Days WARD 3 Daugo Island Open Air 14 Days Koki Settlement Koki Primary School -

Ssgm Working Papers

SSSSGGMM WWORKING PPAPERS Working Paper 2005/1 Political Discourse and Religious Narratives of Church and State in Papua New Guinea Philip Gibbs Melanesian Institute*, Goroka, PNG Dr Philip Gibbs is at the Melanesian Institute, PO Box 571, Goroka, EHP, Papua New Guinea SSGM Working Paper 2005/1 State Society and Governance in Melanesia Project Working Papers The State Society and Governance in Melanesia Project Working Paper series seeks to provide readers with access to current research and analysis on contemporary issues on governance, state and society in Melanesia and the Pacific. Working Papers produced by the Project aim to facilitate discussion and debate in these areas; to link scholars working in different disciplines and regions; and engage the interest of policy communities. Disclaimer The views expressed in publications on this website are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the State, Society and Governance in Melanesia Project. State Society and Governance in Melanesia Project Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200 Tel: +61 2 6125 8394 Fax: +61 2 6125 5525 Email:[email protected] SSGM Working Paper 2005/1 Abstract In Papua New Guinea, attempts to keep religion and politics separate often meet with incomprehension and resistance on the part of the general populace, for in traditional Melanesian terms, religion has a political function: seen in the power to avert misfortune and ways to ensure prosperity and well being. This paper looks at how religious narrative plays a part in contemporary political discourse in Papua New Guinea. It will look first at the links between socio-political and religious institutions, and then will consider some of the ways religious values and symbols are used and exploited to legitimise political aspirations. -

Rotarians Against Malaria

ROTARIANS AGAINST MALARIA LONG LASTING INSECTICIDAL NET DISTRIBUTION REPORT MOROBE PROVINCE Bulolo, Finschafen, Huon Gulf, Kabwum, Lae, Menyamya, and Nawae Districts Carried Out In Conjunction With The Provincial And District Government Health Services And The Church Health Services Of Morobe Province With Support From Against Malaria Foundation and Global Fund 1 May to 31 August 2018 Table of Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. 3 Background ........................................................................................................................... 4 Schedule ............................................................................................................................... 6 Methodology .......................................................................................................................... 6 Results .................................................................................................................................10 Conclusions ..........................................................................................................................13 Acknowledgements ..............................................................................................................15 Appendix One – History Of LLIN Distribution In PNG ...........................................................15 Appendix Two – Malaria In Morobe Compared With Other Provinces ..................................20 -

A Trial Separation: Australia and the Decolonisation of Papua New Guinea

A TRIAL SEPARATION A TRIAL SEPARATION Australia and the Decolonisation of Papua New Guinea DONALD DENOON Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Denoon, Donald. Title: A trial separation : Australia and the decolonisation of Papua New Guinea / Donald Denoon. ISBN: 9781921862915 (pbk.) 9781921862922 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Decolonization--Papua New Guinea. Papua New Guinea--Politics and government Dewey Number: 325.953 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover: Barbara Brash, Red Bird of Paradise, Print Printed by Griffin Press First published by Pandanus Books, 2005 This edition © 2012 ANU E Press For the many students who taught me so much about Papua New Guinea, and for Christina Goode, John Greenwell and Alan Kerr, who explained so much about Australia. vi ST MATTHIAS MANUS GROUP MANUS I BIS MARCK ARCH IPEL AGO WEST SEPIK Wewak EAST SSEPIKEPIK River Sepik MADANG NEW GUINEA ENGA W.H. Mt Hagen M Goroka a INDONESIA S.H. rk ha E.H. m R Lae WEST MOROBEMOR PAPUA NEW BRITAIN WESTERN F ly Ri ver GULF NORTHERNOR N Gulf of Papua Daru Port Torres Strait Moresby CENTRAL AUSTRALIA CORAL SEA Map 1: The provinces of Papua New Guinea vii 0 300 kilometres 0 150 miles NEW IRELAND PACIFIC OCEAN NEW IRELAND Rabaul BOUGAINVILLE I EAST Arawa NEW BRITAIN Panguna SOLOMON SEA SOLOMON ISLANDS D ’EN N TR E C A S T E A U X MILNE BAY I S LOUISIADE ARCHIPELAGO © Carto ANU 05-031 viii W ALLAC E'S LINE SUNDALAND WALLACEA SAHULLAND 0 500 km © Carto ANU 05-031b Map 2: The prehistoric continent of Sahul consisted of the continent of Australia and the islands of New Guinea and Tasmania. -

Badili Badili Badili Badili Badili Badili

Badili K700 /m2/annum Badili K1,100/week Badili K18,500/month 3 1 2 NM1844 - Warehouse for lease - AO NM1727 - Unit for lease - ES NM558 - Rare Warehouses - TG Recently available is the huge warehouse. It’s Now available on the market is this recently built Are you searching for storage and dispatch located in the most sought after commercial zone single level 2 x3 bed room Unit. Located in a safe locations? Is it hard to find an ideal place? Then in Badili. The vertical height is approximately 10 & Quiet neighborhood, with sea view’s across this is it, your search has ended. This warehouse meters and total floor space of 2012 square manubada Island, this could be your Ideal family of 324sqm is located in prime commercial Badili is meters altogether. It would be ideal for cooperate home. Both units comes fully furnished with both the ideal place for your business to thrive. Within companies who need big vertical height size for white and brown goods, a large yard with ample close distance to nearby commercial businesses storage, factory etc… Don’t miss this opportunity, carpark space & is close to all amenities Call OUR and 15minutes drive to Fairfax harbour, it is a call now to book an inspection. SALES TEAM NOW FOR AN INSPECTION must for companies needing quick access and Badili K750 /week Badili K3,000/week Boroko K750 /week 3 1 1 3 2 2 1 1 NM003 - 2 & 3 bedroom Unit up for grabS - ND NM1207 - Spacious Units with Views - SM NM961 - Bedsitter available in Boroko - CK 2 & 3 bedroom single level units with amenities Located in a quiet neighbourhood in Koki are Just a 3 minute walk away from Manu Autoport just a few minutes walk away. -

I2I Text Paste Up

Chapter 4 Impasse The Guise Select Committee John Guise’s Select Committee was scarcely more democratic than Gunther’s. Not only did it contain three expatriate elected members of the House, but also three officials, one of whom (W. W. Watkins, the abrasive Law Officer) became deputy chair, while Fred Chaney was its secretary. Watkins argued for ‘certain matters to be the subject of talks between the Commonwealth Government and the Committee’.1 As members were keen to protect the Australian connection, they consulted Canberra on the following agenda before they consulted the people. Matters for Discussion 1 In the event of the people deciding that they wish Papua and New Guinea to be one country, the following alternatives arise — a that Papua becomes a Trust Territory [with] New Guinea and Papuans become Australian protected persons rather than Australian citizens; or b that New Guinea become[s] an Australian Territory and New Guineans acquire Australian citizenship rather than a status of Australian protected persons; or c that there be a Papuan and New Guinean citizenship. [In any event] there would also be a desire to continue close association with Australia. The Commonwealth Government’s view as to the extent of such an association is sought. 2 Could a statement be made on the application of Commonwealth migration provisions [in each of these cases]. 3 Does the Commonwealth Government consider that a period of internal self- government is desirable … ? 4 [If so,] has the Commonwealth Government any views on [how … any such system should ensure that the best advice possible … is still available to the Administrator who remains responsible for the administration of the Territory Impasse 53 and the carrying out of Commonwealth Government policy so long as Australia provides major financial assistance. -

Evaluation of House Rent Prices and Their Affordability in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea

buildings Article Evaluation of House Rent Prices and Their Affordability in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea Eugene E. Ezebilo Property Development Program, National Research Institute, P.O. Box 5854, Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea; [email protected] or [email protected] Received: 9 September 2017; Accepted: 1 December 2017; Published: 4 December 2017 Abstract: Access to affordable housing has been a long-standing issue for households in most cities. This paper reports on a study of house rent prices in Port Moresby, factors influencing them, and affordability of the prices. Data was obtained from houses that were advertised for rent in Port Moresby for a period of 13 months and were analysed using the ordinary least squares (OLS) regression model. The results show that monthly house rent prices range from 2357 to 34,286 Papua New Guinea Kina (PGK), or 714 to 10,389 U.S. dollars (USD), and the median price was 7286 PGK (2208 USD). Houses located in the central business district had the highest median house rent price, whereas low-income areas had the lowest rent price. By dividing the median house rent price by gross household income, the housing affordability index was 3.4. House rent price was influenced by factors such as number of bedrooms and location. To make house rent prices more affordable for Port Moresby residents, it is necessary to supply more houses for rent relative to demand, especially in low-income areas. Relevant governmental agencies should put more effort toward unlocking more customarily-owned land for housing development and toward facilitating the private sector to construct more low-cost houses for rent, which are affordable for low to middle income households. -

Schedule of Ncd School Transport Bus Routes

STUDENTS ONLY BUS ROUTE 01. GORDONS - 9 MILE (BOMANA) STUDENTS ONLY BUS ROUTE 02. 7 MILE - TOWN MORNINGMORNING RUNS RUNS (3 TRIPS) (3 TRIPS) FLEETS - For3 BUSES 1 Bus MORNINGMORNING RUNS RUNS (3 TRIPS) (3 TRIPS) FLEETS - 3For BUSES 1 Bus OPERATING TIME: 6:20 am SCHEDULE- 9:20 am OF NCD SCHOOL TRANSPORTOPERATING TIME: 6:20 amBUS - 9:20 am ROUTES Trip 1 Trip 2 Trip 3 Trip 1 Trip 2 Trip 3 Time: 6:20 am - 7:20 am Time: 7:20 am - 8:20 am Time: 8:20 am - 9:20 am Time: 6:20 am - 7:20 am Time: 7:20 am - 8:20 am Time: 8:20 am - 9:20 am Bus 1. Bus 1. Bus 1. Bus 1. Bus 1. Bus 1. Origin: Gordons Destination: 9 mile Origin: Gordons Destination: 9 mile Origin: Gordons Destination: 9 mile Origin: 7 mile Destination: Town Origin: 7 mile Destination: Town Origin: 7 mile Destination: Town To From To From To From To From To From To From Bus Stops Time Bus Stops Time Bus Stops Time Bus Stops Time Bus Stops Time Bus Stops Time Bus Stops Time Bus Stops Time Bus Stops Time Bus Stops Time Bus Stops Time Bus Stops Time Gordons 6:20 Bomana 6:47 Gordons 7:20 Bomana 7:45 Gordons 8:20 Bomana 8:45 7 mile 6:20 Town 6:50 7 mile 7:20 Town 7:50 7 mile 8:20 Town 8:50 Erima 6:23 9 mile 7:00 Erima 7:25 9 mile 8:02 Erima 8:25 9 mile 9:02 6 mile 6:24 Koki 6:56 6 mile 7:24 Koki 7:56 6 mile 8:24 Koki 8:56 Wildlife 6:26 8 mile 7:04 Wildlife 7:28 8 mile 8:06 Wildlife 8:28 8 mile 9:06 4 mile 6:34 4 mile 7:06 4 mile 7:34 4 mile 8:06 4 mile 8:34 4 mile 8:06 8 mile 6:29 Wild life 7:10 8 mile 7:31 Wild life 8:11 8 mile 8:31 Wildlife 9:11 Koki 6:44 6 mile 7:15 Koki 7:44 6 mile 8:15 Koki -

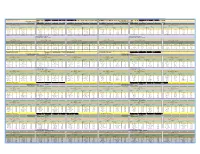

2021 Quarter 1 Payment 1 Batch

2021 QUARTER 1 PAYMENT 1 BATCH 1_Q1P1B121CENPPSV_NCD School CodeSchool Name Sector Code Province Name District Name Account No Bank Name Bb Name Enrollment Balance Pay 69001 BARUNI PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI NATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICTNATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICT1000586837 BSP Port Moresby 429 15,787.20 69002 BAVAROKO PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI NATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICTNATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICT1000489748 BSP Boroko Banking Centr1,957 72,017.60 69003 BOREBOA PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI NATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICTNATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICT1000489754 BSP Lae Market Service1,975 C 72,680.00 69004 DIHAROHA/SEVESE MOREA PRIMARY SCHOOLPRI NATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICTNATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICT1000967421 BSP Port Moresby 1,020 37,536.00 69005 EVEDAHANA PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI NATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICTNATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICT1000489766 BSP Boroko Banking Centr1,871 68,852.80 69006 GOLDIE RIVER PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI NATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICTNATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICT1000489757 BSP Boroko Banking Centr642 23,625.60 69007 GEREHU PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI NATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICTNATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICT1000489746 BSP Boroko Banking Centr2,240 82,432.00 69008 HAGARA PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI NATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICTNATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICT1000585902 BSP Port Moresby 1,548 56,966.40 69009 HOHOLA DEMONSTRATION PRIMARY SCHOOLPRI NATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICTNATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICT1000388432 BSP Boroko Banking Centr1,861 68,484.80 69010 EKI VAKI PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI NATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICTNATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICT1000583810 BSP Waigani Banking Cent1,362 50,121.60 69011 JUNE VALLEY PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI NATIONAL -

CHAPTER 12 INFRASTRUCTURE and SERVICES PLAN (Sectoral)

The Project for the Study on Lae-Nadzab Urban Development Plan in Papua New Guinea CHAPTER 12 INFRASTRUCTURE AND SERVICES PLAN (Sectoral) Spatial and economic development master plans prepared in the previous Chapter 11 are the foundation of infrastructure and social service development projects. In this chapter, the Project target sector sub-projects are proposed based on the sector based current infrastructure and social service status studies illustrated in Chapter 6 of the Report. In particular, transportation sector, water supply sector, sanitation & sewage sector, waste management sector, storm water & drainage sector and social service sector (mainly education and healthcare) are discussed, and power supply sector and telecommunication sector possibilities are indicated. Each of these sub-projects is proposed in order to maximize positive impact to the regional economic development as well as spatial development in the Project Area. Current economic activities and market conditions in the region are taken into consideration with the economic development master plan in order to properly identify local needs of infrastructure and social services. The development of industry to improve economic activities in the region becomes the key to change such livelihood in Lae-Nadzab Area with stable job creation, and proposed infrastructure sub-projects will be so arranged to maximize the integration with economic development. 12.1 Land Transport 12.1.1 Travel Demand Forecasting Figure 12.1.1 shows the flowchart of the travel demand forecasting process of the Project Area. The travel analysis was based on the traditional four-step model. The data from the household survey, person trip survey, traffic count survey and roadside interview survey were the main inputs of the analysis. -

Papua Nueva Guinea

PAPÚA NUEVA GUINEA Julio 2003 PAPÚA NUEVA GUINEA 182 / 2003 ÍNDICE Pág. I. DATOS BÁSICOS . 1 II. DATOS HISTÓRICOS . 8 III. CONSTITUCIÓN Y GOBIERNO . 18 IV. RELACIONES CON ESPAÑA . 21 1. Diplomáticas . 21 2. Económicas . 22 3. Intercambio de visitas . 23 a) Personalidades papúes a España . 23 V. DATOS DE LA REPRESENTACIÓN ESPAÑOLA . 24 FUENTES DOCUMENTALES . 25 I. DATOS BÁSICOS Características generales Nombre oficial: Estado independiente de Papúa Nueva Guinea (Papua New Guinea; Papua Niugini). Superficie: 462.800 km². Población: 5.300.000 hab. (2001). Capital: Port Moresby (193.000 hab.). Otras ciudades: Lae, 78.000 hab.; Madang, 27.000 hab.; Wewak, 23.000 hab.; Goroka, 18.000 hab. Grupos étnicos: Hay numerosos grupos étnicos en las 20 provincias de Papua Nueva Guinea. Papúes: 84%, melanesios: 15% y otros: 1%. Lengua: Inglés, pidgin y motu (oficiales), papú y aproximada- mente 750 lenguas indígenas. Religión: 58,4% protestantes; 32,8% católicos; 5,4% anglicanos; 3,1% cultos tradicionales indígenas; 0,3% otros. Bandera: Está dividida diagonalmente desde el ángulo supe- rior izquierdo al inferior derecho. La parte superior muestra un ave del paraíso dorada sobre fondo rojo. La parte inferior tiene cinco estrellas blancas de cinco puntas en forma de la constelación de la Cruz del Sur sobre fondo negro. Moneda: Kina (K) = 100 toea Geografía: El país comprende la mitad oriental de la isla de Nue- va Guinea, el archipiélago de Bismarck, las islas del Almirantazgo, Trobriand y D’Entrecasteaux, el archi- piélago de las Luisiadas y las más septentrionales de – 1 – las islas Salomón. El suelo es casi totalmente de origen volcánico y muy montañoso. -

Module 3.3 Papua New Guinea History – an Overview Student

Social and Spiritual Development Social Science Unit 3: Transition and Change Module 3.3 Papua New Guinea History – An Overview Student Support Material ii Module 3.3 PNG History – An Overview Acknowledgements Materials written and compiled by Sue Lauer, Helen Walangu (PNGEI), Francis Mahap (MTC) and Michael Homingu (HTTC). Layout and diagrams supported by Nick Lauer. Date: 28 March 2002 Cover picture: An affray at Traitors' Bay. On the 9th May 1873, HMS Basilisk was taking on wood at Traitors' Bay (Mambare Bay near Cape Ward Hunt) when a party of local inhabitants threatened three of the ship's officers who were walking on shore. Captain Moresby, who had come ashore to warn his officers of their danger, fired a shot at the leading man which pierced his shield but did not wound him. 'There was no need to fire again and take life,' reported Moresby, 'for the whole body of warriors turned instantly, in consternation, and ran for canoes, and we followed till we drove then on board. Source: Gash & Whittaker (1989). All photographs in the text and the cover are from: Gash & Whittaker (1989): A Pictorial History of New Guinea. Carina: Robert Brown and Associates PASTEP Primary and Secondary Teacher Education Project Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID) GRM International Papua New Guinea-Australia Development Cooperation Program Student Support Material Module 3.3 PNG History – An Overview iii Unit outline 3.1 Skills for Investigating Change (Core) 3.2 Independence (Core) 3.3 PNG History – an Overview Unit 3 (Optional) Transition