Rauschenberg, Kafka, and the Boundaries of Imagination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Robert Rauschenberg: Among Friends Final Audioguide Script – May 8, 2017

The Museum of Modern Art Robert Rauschenberg: Among Friends Final Audioguide Script – May 8, 2017 Stop List 800. Introduction 801. Robert Rauschenberg and Susan Weil, Double Rauschenberg, c. 1950 802. Robert Rauschenberg, Untitled (Black Painting with Asheville Citizen), c. 1952 8021. Underneath Asheville Citizen 803. Robert Rauschenberg, White Painting, 1951, remade 1960s 804. Robert Rauschenberg, Untitled (Scatole personali) (Personal boxes), 1952-53 805. Robert Rauschenberg with John Cage, Automobile Tire Print, 1953 806. Robert Rauschenberg with Willem de Kooning and Jasper Johns, Erased de Kooning, 1953 807. Robert Rauschenberg, Bed, 1955 8071. Robert Rauschenberg’s Combines 808. Robert Rauschenberg, Minutiae, 1954 809. Robert Rauschenberg, Thirty-Four Illustrations for Dante's Inferno, 1958-60 810. Robert Rauschenberg, Canyon, 1959 811. Robert Rauschenberg, Monogram, 1955-59 812. Jean Tinguely, Homage to New York, 1960 813. Robert Rauschenberg, Trophy IV (for John Cage), 1961 814. Robert Rauschenberg, Homage to David Tudor (performance), 1961 815. Robert Rauschenberg, Pelican, (performance), 1963 USA20415F – MoMA – Robert Rauschenberg: Among Friends Final Script 1 816. Robert Rauschenberg, Retroactive I, 1965 817. Robert Rauschenberg, Oracle, 1962-65 818. Robert Rauschenberg with Carl Adams, George Carr, Lewis Ellmore, Frank LaHaye, and Jim Wilkinson, Mud Muse, 1968-71 819. John Chamberlain, Forrest Myers, David Novros, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg, and Andy Warhol with Fred Waldhauer, The Moon Museum, 1969 820. Robert Rauschenberg, 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering, 1966 (Poster, ephemera) 821. Robert Rauschenberg, Cardboards, 1971-1972 822. Robert Rauschenberg, Jammers (series), 1974-1976 823. Robert Rauschenberg, Glut (series), 1986-97 824. Robert Rauschenberg, Glacial Decoy (series of 620 slides and film), 1979 825. -

Perpetual Inventory Author(S): Rosalind Krauss Source: October, Vol

Perpetual Inventory Author(s): Rosalind Krauss Source: October, Vol. 88 (Spring, 1999), pp. 86-116 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/779226 . Accessed: 01/05/2013 15:51 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to October. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.114.163.7 on Wed, 1 May 2013 15:51:29 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions PerpetualInventory* ROSALINDKRAUSS I wentin for myinterview for thisfantastic job. ... Thejob had a greatname-I might use itfor a painting-"PerpetualInventory." -Rauschenberg to Barbara Rose 1. Here are threedisconcerting remarks and one document: The firstsettles out from a discussion of the various strategies Robert Rauschenbergfound to defamiliarizeperception, so that, in Brian O'Doherty's terms,"the citydweller's rapid scan" would now displace old habits of seeing and "the art audience's stare" would yield to "the vernacularglance."I With its vora- ciousness,its lack of discrimination,its wanderingattention, -

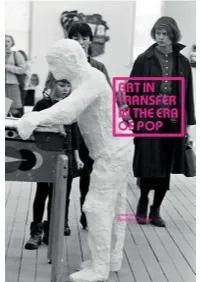

Art in Transfer in the Era of Pop

ART IN TRANSFER IN THE ERA OF POP ART IN TRANSFER IN THE ERA OF POP Curatorial Practices and Transnational Strategies Edited by Annika Öhrner Södertörn Studies in Art History and Aesthetics 3 Södertörn Academic Studies 67 ISSN 1650-433X ISBN 978-91-87843-64-8 This publication has been made possible through support from the Terra Foundation for American Art International Publication Program of the College Art Association. Södertörn University The Library SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications © The authors and artists Copy Editor: Peter Samuelsson Language Editor: Charles Phillips, Semantix AB No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Cover Image: Visitors in American Pop Art: 106 Forms of Love and Despair, Moderna Museet, 1964. George Segal, Gottlieb’s Wishing Well, 1963. © Stig T Karlsson/Malmö Museer. Cover Design: Jonathan Robson Graphic Form: Per Lindblom & Jonathan Robson Printed by Elanders, Stockholm 2017 Contents Introduction Annika Öhrner 9 Why Were There No Great Pop Art Curatorial Projects in Eastern Europe in the 1960s? Piotr Piotrowski 21 Part 1 Exhibitions, Encounters, Rejections 37 1 Contemporary Polish Art Seen Through the Lens of French Art Critics Invited to the AICA Congress in Warsaw and Cracow in 1960 Mathilde Arnoux 39 2 “Be Young and Shut Up” Understanding France’s Response to the 1964 Venice Biennale in its Cultural and Curatorial Context Catherine Dossin 63 3 The “New York Connection” Pontus Hultén’s Curatorial Agenda in the -

London Exhibition Roundup

Buck, Louisa. “London exhibition roundup: a glut of Rauschenberg treats at Tate, the aftermath of Post-Modernism, a De Chirico-inspired group show and Thuring’s trompe l’oeil tapestries,” The Art Newspaper Online. 12 December 2016 London exhibition roundup: a glut of Rauschenberg treats at Tate, the aftermath of Post-Modernism, a De Chirico-inspired group show and Thuring’s trompe l’oeil tapestries by LOUISA BUCK | 12 December 2016 Robert Rauschenberg's Untitled (Spread) (1983) (Image: © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York) Revolt of the Sage, Blain Southern (until 21 January) This ambitious, disquietingly atmospheric show takes its title from a 1916 work by Georgio De Chirico. The picture itself is deliberately absent, but the Italian painter’s moody notion of a mysterious metaphysical realm, redolent of loss and longing and in which “the past is the same as the future…” permeates a diverse lineup of leading contemporary artists. These include Goshka Macuga, Christian Marclay and John Stezaker, which here are made to spark-up unexpected conversations with more historical post-war works by Lynn Chadwick, Jannis Kounellis and Sigmar Polke. Installation view of Revolt of the Sage (2016) (Courtesy of the artists and Blain|Southern. Photo: Peter Mallet) While none of the above—or any of the show’s artists—are Surrealist per se, the collective subconscious is given a thorough prodding as, in multifarious ways, images are fragmented, reframed and/or distorted. In Stezaker’s haunting collages the face from a vintage photographic portrait is replaced by a landscape, or film stills made to merge into and out of their settings; while Sigmar Polke’s prints violently smear found newspaper images. -

Of Rauschenberg, Policy and Representation

OF RAUSCHENBERG, POLICY AND REPRESENTATION AT THE VANCOUVER ART GALLERY: A PARTIAL HISTORY 1966 - 1983 By JOHN STEVEN HARRIS B.A., The University of British Columbia, 1980 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Fine Arts) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA October 1985 0 John Steven Harris, 1985 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of T~ ><^.e- The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 / Date tCO^Ue^^n^ ABSTRACT My thesis examines the policy of the Vancouver Art Gallery (VAG) as it affected the representation of art in its community in the 1960s and '70s. It was begun in order to understand what determined the changes in policy as they were experienced during this period, which saw an enormous expansion in the activities of the Gallery. To some extent the expansion was realized by means of increased cultural expenditure by the federal government, but this only made programmes possible, it did not carry them out. -

Rauschenberg P.R

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART WILL PRESENT A FULL RETROSPECTIVE OF ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG IN MAY 2017 Artist Charles Atlas to Collaborate on Exhibition Design NEW YORK, December 1, 2016 (Updated January 11, 2017)—Robert Rauschenberg: Among Friends, a retrospective spanning the six-decade career of this defining figure of contemporary art, will be on view at The Museum of Modern Art from May 21 until September 17, 2017. Organized in collaboration with Tate Modern in London, this exhibition brings together over 250 works, integrating Rauschenberg’s astonishing range of production across mediums including painting, sculpture, drawing, prints, photography, sound works, and performance footage. Robert Rauschenberg is organized by Leah Dickerman, The Marlene Hess Curator of Painting and Sculpture, The Museum of Modern Art, and Achim Borchardt-Hume, Director of Exhibitions at Tate Modern, with Emily Liebert and Jenny Harris, Curatorial Assistants, Department of Painting and Sculpture, The Museum of Modern Art. The exhibition’s design at MoMA is created in collaboration with acclaimed artist and filmmaker Charles Atlas. In addition to its presentation in New York this spring, Robert Rauschenberg will be shown at Tate Modern (December 1, 2016–April 2, 2017) and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) (November 4, 2017–March 25, 2018). In 1959, Robert Rauschenberg (American, 1925–2008) wrote, “Painting relates to both art and life. Neither can be made. (I try to act in that gap between the two.)” His work in this gap shaped artistic practice for the years to come. The early 1950s, when Rauschenberg launched his career, was the heyday of heroic gestural painting of Abstract Expressionism. -

Mother of God

Mother of God By Susan Davidson, July 2013 Part of the Rauschenberg Research Project Cite as: Susan Davidson, “Mother of God,” Rauschenberg Research Project, July 2013. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, http://www.sfmoma.org/artwork/98.299/essay/ mother-of-god/. 1 Over the past twenty years, scholarship on Robert Rauschenberg’s early artistic development has been largely informed by the exhibition and monograph organized in 1991 by Walter Hopps for the Menil Collection in Houston. In the installation and its related catalogue, both titled Robert Rauschenberg: The Early 1950s, Hopps closely examined the groundbreaking experimentation undertaken by Rauschenberg between 1949 and 1954, charting the emergence of the principal themes and motifs that would come to define the sixty-year arc of the artist’s career. During that seminal period, Rauschenberg established an ongoing interest in grasping the full range of art-making mediums, including printmaking, painting, photography, drawing, sculpture, and conceptual modes, often blurring categorical distinctions by using multiple techniques and materials in combination. Mother of God (ca. 1950), part of an informal group of artworks that was included in his first solo exhibition at Betty Parsons Gallery, New York, in 1951, is a key example of the innovations Rauschenberg achieved in those years. It is worth recounting here some of the details of the artist’s early biography in order to understand the origins and implicit meanings of Mother of God. 2 Growing up in the Gulf Coast town of Port Arthur, Texas—once home to the world’s largest concentration of oil refineries—Rauschenberg had little exposure to art despite 1. -

Strategic Ambiguity in Avant-Garde Painting

Wesleyan University The Honors College Strategic Ambiguity in Avant-Garde Painting by John Beeson Class of 2009 A thesis submitted to the faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Departmental Honors in Art History Middletown, Connecticut April, 2009 Contents ——— Illustrations page 2 Introduction 4 1 Willem de Kooning 31 2 Robert Rauschenberg 72 3 Jasper Johns 112 4 Cy Twombly 145 Conclusion 177 Bibliography 187 1 Illustrations ——— 1. Installation view: the Modern Wing of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, page 3 New York, Summer 2008 2. Installation view: Robert Rauschenberg at The Jewish Museum, 1963. 20 With Robert Rauschenberg, Monogram, 1955-1959 3. Willem de Kooning, Easter Monday, 1955-56 32 4A and 4B. Detail of Easter Monday and advertisement for Schraff’s treats 46 5A and 5B. Detail of Easter Monday and Marcel Duchamp, Tu m’, 1918 49 6A and 6B. Detail of Easter Monday and advertisement for Alexander the Great 51 7. Willem de Kooning, Woman as a Landscape, 1955 57 8. Willem de Kooning, Asheville, 1949 63 9. Willem de Kooning, Untitled (Drawings with eyes closed), 1966 67 10. Robert Rauschenberg, Erased de Kooning Drawing, 1953 76 11. Robert Rauschenberg, Winter Pool, 1959 82 12. Jasper Johns, White Flag, 1955 113 13. Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1917 134 14. Cy Twombly, Untitled, 1970 146 15. Detail from Palmer Method for Business Handwriting, 1935 Edition 155 16. Cy Twombly, Academy, 1955 167 2 1. Installation view of the Modern Wing, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2008. -

Robert Rauschenberg: Thirty-Four Illustrations for Dante’S Inferno Leah Dickerman Is the Marlene Hess Curator of Painting and Sculpture ARTBOOK | D.A.P

Published by The Museum of Modern Art Contributors 11 West 53 Street Robin Coste Lewis is a Provost’s Fellow in Poetry and Visual Studies at New York, New York 10019 the University of Southern California and the author of Voyage of the Sable www.moma.org Venus (2015), winner of the National Book Award for Poetry. Distributed in the United States and Canada by Robert Rauschenberg: Thirty-Four Illustrations for Dante’s Inferno Leah Dickerman is The Marlene Hess Curator of Painting and Sculpture ARTBOOK | D.A.P. at The Museum of Modern Art, New York. 155 Sixth Avenue, 2nd Floor etween 1958 and 1960, Robert Rauschenberg made robert New York, New York 10013 drawings for each of the thirty-four cantos, or sections, Kevin Young is Director of the Schomburg Center for Research in www.artbook.com B Black Culture and the author of eleven books of poetry and prose, most of Dante’s fourteenth-century poem Inferno by using a novel recently Blue Laws: Selected & Uncollected Poems 1995–2015 (2016), which Distributed outside the United States and Canada by technique to transfer photographic reproductions from was long-listed for the National Book Award. Thames & Hudson Ltd. rauschenberg 181A High Holborn magazines or newspapers onto paper. Acquired by The London WC1V 7QX Museum of Modern Art soon after it was completed, the www.thamesandhudson.com resulting work is his most sustained exercise in the medium of drawing and a testament to Rauschenberg’s desire to Front cover: Robert Rauschenberg. Canto XIV: Circle Seven, Round 3, the Violent against God, Nature, and Art from the series Thirty-Four Illustrations bring his experience of the contemporary world into his for Dante’s Inferno. -

Acting in the Gap Between Art and Life the Early Years – from Texas to New York Focus 1 Photography Monochromes and Experi

5 ACTING IN THE GAP BETWEEN ART AND LIFE 7 THE EARLY Years – frOM TEXAS TO NEW YORK 18 FOCUS 1 PHOTOGRAPHY 23 MONOCHROMES AND EXPERIMENTAL WORKS 44 FOCUS 2 ERASED DE KOONING DRAWING 47 THE COMBINES 70 FOCUS 3 MONOGRAM 75 TRANSFER DRAWINGS, PRINTMAKING AND THE SILKSCREEN PAINTINGS 84 FOCUS 4 Dante’s INFERNO 87 FOCUS 5 BARGE 93 BEYOND PAINTING: THE LATE 1960S AND EARLY 1970S 103 FOCUS 6 TECHNOLOGY 108 FOCUS 7 PERFORMANCE 113 FOCUS 8 FABRIC 117 RETURN TO PAINTING AND PHOTOGRAPHY 136 FOCUS 9 RAUSCHENBERG OVERSEAS CULTURE INTERCHANGE (ROCI) 140 FOCUS 10 BIBLE BIKE (BOREALIS) 142 CHRONOLOGY 145 FURTHER READING 146 LIST OF WORKS ACTING IN THE GAP BETWEEN ART AND LIFE In 1959, Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008) declared, ‘Painting relates to both art and life. Neither can be made. (I try to act in that gap between the two.)’ In his Combines, works melding painting and sculpture, Rauschenberg brought elements of everyday life into his art through the process of collage. Developed by Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) and Georges Braque (1882–1963) and used by many members of the avant-garde that flourished between the two world wars, collage enlivened artists’ compositions by introducing extraneous materials, usually in the form of pasted papers and small objects. Rauschenberg brought a new scale and physicality to collage by integrating a staggering array of materials into his compositions, from photographs, picture postcards and T-shirts to dripping swathes of paint, Coca-Cola bottles and stuffed chickens. ‘A pair of socks,’ he insisted, ‘is no less suitable to make a painting with than wood, nails, turpentine, oil and fabric.’ Rauschenberg’s ‘gap’ became the site of more than half a century of endeavours through which he redefined not only what materials could comprise a work of art but what a work of art could be – and, by extension, what it meant to be an artist. -

Combines (1953-1964) 11 October 2006 - 15 January 2007, Gallery 2, Level 6

Education / Media supports Exhibition itinerary > Texte français ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG COMBINES (1953-1964) 11 OCTOBER 2006 - 15 JANUARY 2007, GALLERY 2, LEVEL 6 Monogram, 1955-59. Freestanding combine Introduction When creation means combining, assembling, incorporating Parody and its different manifestations The relationship of artwork with time Bibliography INTRODUCTION Following on from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, the Centre Pompidou, Musée National d’art moderne presents, from 11 October 2006 to 15 January 2007, the exhibition entitled “Robert Rauschenberg: Combines (1953-1964)”. In the early 1950s, Rauschenberg launched his artistic career with series of monochrome paintings in black, white, gold and red, featuring varied textural effects produced by the marouflage and painting of newspaper. Even then he wanted to abolish from art the sacrosanct principle of self-expression. These surfaces, and in particular his white paintings, offer themselves as mirrors, neutral surfaces waiting to accept the reflections of the world. “Today is their creator,” the artist once said of these works. The Combines period followed immediately after. “Rauschenberg: Combines” is the first exhibition dedicated exclusively to this essential creative phase of the artist, which marked the beginning of his international artistic influence. As the name suggests, the Combines are hybrid works that associate painting with collage and assemblage of a wide range of objects taken from everyday life. Neither paintings nor sculptures, but both at once, Rauschenberg’s Combines invade the viewers’ space, demanding their attention, like veritable visual puzzles. From stuffed birds to Coca-Cola bottles, from newspaper to press photos, fabric, wallpaper, doors and windows, it is as though the whole universe enters into his combinatorial process to join forces with paint.