Dialogue Lecture Series, Vaal University of Technology, Vereeniging, 20 October, 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malibongwe Let Us Praise the Women Portraits by Gisele Wulfsohn

Malibongwe Let us praise the women Portraits by Gisele Wulfsohn In 1990, inspired by major political changes in our country, I decided to embark on a long-term photographic project – black and white portraits of some of the South African women who had contributed to this process. In a country previously dominated by men in power, it seemed to me that the tireless dedication and hard work of our mothers, grandmothers, sisters and daughters needed to be highlighted. I did not only want to include more visible women, but also those who silently worked so hard to make it possible for change to happen. Due to lack of funding and time constraints, including raising my twin boys and more recently being diagnosed with cancer, the portraits have been taken intermittently. Many of the women photographed in exile have now returned to South Africa and a few have passed on. While the project is not yet complete, this selection of mainly high profile women represents a history and inspiration to us all. These were not only tireless activists, but daughters, mothers, wives and friends. Gisele Wulfsohn 2006 ADELAIDE TAMBO 1929 – 2007 Adelaide Frances Tsukudu was born in 1929. She was 10 years old when she had her first brush with apartheid and politics. A police officer in Top Location in Vereenigng had been killed. Adelaide’s 82-year-old grandfather was amongst those arrested. As the men were led to the town square, the old man collapsed. Adelaide sat with him until he came round and witnessed the young policeman calling her beloved grandfather “boy”. -

The Black Sash

THE BLACK SASH THE BLACK SASH MINUTES OF THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE 1990 CONTENTS: Minutes Appendix Appendix 4. Appendix A - Register B - Resolutions, Statements and Proposals C - Miscellaneous issued by the National Executive 5 Long Street Mowbray 7700 MINUTES OF THE BLACK SASH NATIONAL CONFERENCE 1990 - GRAHAMSTOWN SESSION 1: FRIDAY 2 MARCH 1990 14:00 - 16:00 (ROSEMARY VAN WYK SMITH IN THE CHAIR) I. The National President, Mary Burton, welcomed everyone present. 1.2 The Dedication was read by Val Letcher of Albany 1.3 Rosemary van wyk Smith, a National Vice President, took the chair and called upon the conference to observe a minute's silence in memory of all those who have died in police custody and in detention. She also asked the conference to remember Moira Henderson and Netty Davidoff, who were among the first members of the Black Sash and who had both died during 1989. 1.4 Rosemary van wyk Smith welcomed everyone to Grahamstown and expressed the conference's regrets that Ann Colvin and Jillian Nicholson were unable to be present because of illness and that Audrey Coleman was unable to come. All members of conference were asked to introduce themselves and a roll call was held. (See Appendix A - Register for attendance list.) 1.5 Messages had been received from Errol Moorcroft, Jean Sinclair, Ann Burroughs and Zilla Herries-Baird. Messages of greetings were sent to Jean Sinclair, Ray and Jack Simons who would be returning to Cape Town from exile that weekend. A message of support to the family of Anton Lubowski was approved for dispatch in the light of the allegations of the Minister of Defence made under the shelter of parliamentary privilege. -

Anc Today Voice of the African National Congress

ANC TODAY VOICE OF THE AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 14 – 20 May 2021 Conversations with the President South Africa waging a struggle that puts global solidarity to the test n By President Cyril Ramaphosa WENTY years ago, South In response, representatives of massive opposition by govern- Africa was the site of vic- the pharmaceutical industry sued ment and civil society. tory in a lawsuit that pitted our government, arguing that such public good against private a move violated the Trade-Relat- As a country, we stood on princi- Tprofit. ed Aspects of Intellectual Property ple, arguing that access to life-sav- Rights (TRIPS). This is a compre- ing medication was fundamental- At the time, we were in the grip hensive multilateral agreement on ly a matter of human rights. The of the HIV/Aids pandemic, and intellectual property. case affirmed the power of trans- sought to enforce a law allowing national social solidarity. Sev- us to import and manufacture The case, dubbed ‘Big Pharma eral developing countries soon affordable generic antiretroviral vs Mandela’, drew widespread followed our lead. This included medication to treat people with international attention. The law- implementing an interpretation of HIV and save lives. suit was dropped in 2001 after the World Trade Organization’s Closing remarks by We are embracing Dear Mr President ANC President to the the future! Beware of the 12 NEC meeting wedge-driver: 4 10 Unite for Duma Nokwe 2 ANC Today CONVERSATIONS WITH THE PRESIDENT (WTO) Agreement on Trade-Re- ernment announced its support should be viewed as a global pub- lated Aspects of Intellectual Prop- for the proposal, which will give lic good. -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

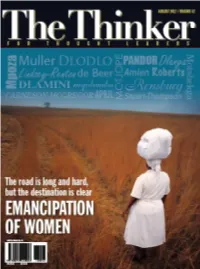

The Thinker Congratulates Dr Roots Everywhere

CONTENTS In This Issue 2 Letter from the Editor 6 Contributors to this Edition The Longest Revolution 10 Angie Motshekga Sex for sale: The State as Pimp – Decriminalising Prostitution 14 Zukiswa Mqolomba The Century of the Woman 18 Amanda Mbali Dlamini Celebrating Umkhonto we Sizwe On the Cover: 22 Ayanda Dlodlo The journey is long, but Why forsake Muslim women? there is no turning back... 26 Waheeda Amien © GreatStock / Masterfile The power of thinking women: Transformative action for a kinder 30 world Marthe Muller Young African Women who envision the African future 36 Siki Dlanga Entrepreneurship and innovation to address job creation 30 40 South African Breweries Promoting 21st century South African women from an economic 42 perspective Yazini April Investing in astronomy as a priority platform for research and 46 innovation Naledi Pandor Why is equality between women and men so important? 48 Lynn Carneson McGregor 40 Women in Engineering: What holds us back? 52 Mamosa Motjope South Africa’s women: The Untold Story 56 Jennifer Lindsey-Renton Making rights real for women: Changing conversations about 58 empowerment Ronel Rensburg and Estelle de Beer Adopt-a-River 46 62 Department of Water Affairs Community Health Workers: Changing roles, shifting thinking 64 Melanie Roberts and Nicola Stuart-Thompson South African Foreign Policy: A practitioner’s perspective 68 Petunia Mpoza Creative Lens 70 Poetry by Bridget Pitt Readers' Forum © SAWID, SAB, Department of 72 Woman of the 21st Century by Nozibele Qutu Science and Technology Volume 42 / 2012 1 LETTER FROM THE MaNagiNg EDiTOR am writing the editorial this month looks forward, with a deeply inspiring because we decided that this belief that future generations of black I issue would be written entirely South African women will continue to by women. -

Specialflash259-14-02-2017.Pdf

Issue 259 | 14 February 2017 ∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙ UBUNTU AWARDS 2017: “CELEBRATING OR TAMBO … IN HIS FOOTSTEPS” The annual awards, hosted by the Department of International Relations and Cooperation (DIRCO), are held to celebrate South African citizens who play an active role in projecting a positive image of South Africa internationally through their good work. The third annual Ubuntu Awards were on Saturday, 11 February, at the Cape Town International Convention Centre, under the theme: “Celebrating OR Tambo … In his Footsteps”. This year’s awards marked the centenary of struggle icon, Oliver Reginald Tambo, who was the longest-serving President of the African National Congress. Born in 1917, the late struggle stalwart, who passed away in 1993, would have turned 100 years old this year. Addressing guests at the glittering event, the Minister of International Relations and Cooperation, Maite Nkoana-Mashabane, said the ceremony had over the past three years proved to be an important and popular programmatic activity that followed the State of Nation Address. “It resonates well with our people and our collective desire to celebrate our very own leaders, and citizens who go beyond the call of duty in their respective industries to contribute to the betterment of this country as well as its general populace.” Reflecting on the theme of the event, Minister Nkoana-Mashabane said: “We are proud to celebrate the life and times of this national icon, a revered statesman and a gallant fighter of our liberation struggle. He worked with his generation to shape our country’s vision and constitutional value system as well as the foundations and principles of our domestic and foreign policy outlook. -

Footprints on the Sands of Time;

FOOTPRINTS IN THE SANDS OF TIME CELEBRATING EVENTS AND HEROES OF THE STRUGGLE FOR FREEDOM AND DEMOCRACY IN SOUTH AFRICA 2 3 FOOTPRINTS LABOUR OF LOVE IN THE SANDS OF TIME Unveiling the Nkosi Albert Luthuli Legacy Project in August 2004, President Thabo Mbeki reminded us that: “... as part of the efforts to liberate ourselves from apartheid and colonialism, both physically and mentally, we have to engage in the process of telling the truth about the history of our country, so that all of our people, armed with this truth, can confidently face the challenges of this day and the next. ISBN 978-1-77018-205-9 “This labour of love, of telling the true story of South Africa and Africa, has to be intensified on © Department of Education 2007 all fronts, so that as Africans we are able to write, present and interpret our history, our conditions and All rights reserved. You may copy material life circumstances, according to our knowledge and from this publication for use in non-profit experience. education programmes if you acknowledge the source. For use in publication, please Courtesy Government Communication and Information System (GCIS) obtain the written permission of the President Thabo Mbeki “It is a challenge that confronts all Africans everywhere Department of Education. - on our continent and in the Diaspora - to define ourselves, not in the image of others, or according to the dictates and Enquiries fancies of people other than ourselves ...” Directorate: Race and Values, Department of Education, Room 223, President Mbeki goes on to quote from a favourite 123 Schoeman Street, Pretoria sub·lime adj 1. -

MANDELA and APARTHEID

MANDELA and APARTHEID 0. MANDELA and APARTHEID - Story Preface 1. APARTHEID in SOUTH AFRICA 2. NELSON MANDELA 3. MANDELA and APARTHEID 4. MANDELA at ROBBEN ISLAND 5. FREE MANDELA 6. MANDELA BECOMES PRESIDENT 7. RUGBY and the SPRINGBOKS 8. FRANCOIS PIENAAR 9. ONE TEAM, ONE COUNTRY 10. PLAY FOR THESE PEOPLE 11. THE GAME THAT MADE A NATION 12. MADIBA and PIENAAR - POST-WIN Nelson Mandela strongly opposed South Africa's system of apartheid. He was willing to go to prison in exchange for his efforts to oppose the system. This image depicts letters, written by Mandela, which are included in his prison correspondence journal. The documents are part of the Google Mandela Archive. (Google donated a significant sum of money to have Mandela-related pictures and documents digitized.) As Mandela continued his education in the real world of South African life, he became more political. Indignities against blacks (don't miss this BBC video archive) existed everywhere. Why couldn't they vote? Why did they need passbooks (providing personal details) to travel inside their own country? Why weren’t black students given the same educational opportunities as white students? Why did black South Africans need separate bantustans (tribal "homelands), located in rural (not gold-and-diamond- producing) areas?" Some of the more egregious apartheid laws were these: Population Registration Act (1950). This law divided South Africa’s people into racial groups. In descending order of privilege, they were: Whites, “Coloreds,” Indians and Blacks. Group Areas Act (1950). Whites and blacks were prohibited from living in the same parts of town. -

South Africa

SOUTHERN AFRICA PROJECT SOUTH AFRICA: TIlE COUNTDOWN TO ELECTIONS Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law 1450 G Street, N.W., Suite 400 • Washington, D.C. 20005 • (202) 662-8342 Issue 5: I anuary 28, 1994 ANC ANNOUNCES NATIONAL LIST FOR NATIONAL ASSEMBLY On January 24th, the African National Congress made public its National Election List for the National Assembly. As reported in the previous issue of Countdown, names will be drawn from the list below to fill seats in the legislature in the order that they appear on the list. Prominent people not appearing on the list such as ANC Deputy Secretary General Jacob Zuma have chosen to serve at the provincial level. [See Issue 4]. Profiles of nominees and lists submitted by other parties will appear in subsequent issues of Countdown. I. Nelson R Mandela 40. Mavivi Manzini 79 . Elijah Barayi 2. Cyril M Ramaphosa 41. Philip Dexter 80. Iannie Momberg 3. Thabo Mbeki 42. Prince lames Mahlangu 81. Prince M. Zulu 4. Ioe Siovo 43. Smangaliso Mkhatshwa 82. Elias Motswaledi 5. Pallo Iordan 44. Alfred Nzo 83. Dorothy Nyembe 6. lay Naidoo 45. Alec Erwin 84. Derek Hanekom 7. Ahmed Kathrada 46. Gregory Rockman 85. Mbulelo Goniwe 8. Ronnie Kasrils 47. Gill Marcus 86. Melanie Verwoerd 9. Sydney Mufamadi 48. Ian van Eck 87. Sankie Nkondo 10. Albertina Sisulu 49. Thandi Modise 88. Pregs Govender II. Thozamile Botha 50. Shepherd Mdladlana 89 . Lydia Kompe 12. Steve Tshwete 51. Nkosazana Zuma 90. Ivy Gcina 13. Bantu Holomisa 52. Nosiviwe Maphisa 91. Ela Ghandi 14. IeffRadebe 53. R. van den Heever 92. -

New Trends and Issues Proceedings on Humanities and Social Sciences Issue 7 (2016) 01-11

New Trends and Issues Proceedings on Humanities and Social Sciences Issue 7 (2016) 01-11 Selected paper of 3rd Global Conference on Linguistics and Foreign Language Teaching (LINELT 2015) 16-18 November 2015, Istanbul University, Istanbul – Turkey Africa’s White Women Karin Ilona Paaschea *, Independent Researcher, Nairobi 00200, Kenya Suggested Citation: Paasche, K. I. (2016). Africa’s White Women. New Trends and Issues Proceedings on Humanities and Social Sciences. [Online]. 07, pp 01-11. Available from: www.prosoc.eu Selection and peer review under responsibility of Prof. Dr. Ali Rahimi, University of Bangkok ©2016 SciencePark Research, Organization & Counseling. All rights reserved. Abstract The place of Africa’s white woman is ambivalent. Often called the oppressed oppressor, she is not a protagonist in her own right. Yet history tells of her crucial contribution to Africa’s freedom struggle. Frantz Fanon says black men believe being loved by her is to be loved “like a white man” and so be white. Doris Lessing’s “poor white” man’s bored wife wants sex with the houseboy. Nadine Gordimer portrays her as a pale, insipid counterpart to African women’s vital beauty pictured in terms disturbingly similar to those characterizing noble savages. In J.M. Coetzee’s Disgrace African men inflict “corrective rape” on her. Black African writers portray her more compassionately. Ngugi wa Thiong’o speaks of “the reduction of white women to nothing.” In Peter Abrahams’s works she joins Africa’s freedom struggle yet becomes the victim of an African freedom fighter’s ruthless exploitation. Mariama Ba depicts her as mercilessly exploited by her black African husband who proves his manhood through her even as he secretly appropriates her resources for his own purposes. -

Mangosuthu Buthelezi and the Appropriation

1 Bongani Ngqulunga A MANDATE TO LEAD: Deputy Director of the Johannesburg Institute MANGOSUTHU BUTHELEZI AND for Advanced Study (JIAS), THE APPROPRIATION OF PIXLEY University of Johannesburg, Email: [email protected] KA ISAKA SEME’S LEGACY DOI: https://dx.doi. org/10.18820/24150509/ Abstract: JCH43.v2.1 This article discusses the appropriation of Seme’s name ISSN 0258-2422 (Print) and political legacy by Mangosuthu Buthelezi, the leader ISSN 2415-0509 (Online) of the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP). While Buthelezi has always invoked Seme’s name in his long political career, Journal for Contemporary the analysis in the article focuses on two periods. The first History was the 1980s when Buthelezi’s political party, Inkatha 2018 43(2):1-14 Yenkululeko Yesizwe, was involved in a fierce competitive © Creative Commons With struggle for political hegemony with the exiled African Attribution (CC-BY) National Congress (ANC) and its allies inside the country. During this period, Buthelezi used Seme’s name to serve as a shield to protect him from political attacks from his adversaries in the broad ANC alliance. After the advent of democracy in the early 1990s, the political hostilities of the 1980s between the ANC and the IFP cooled down and the two parties worked together in the Government of National Unity (GNU). It was during this period that Buthelezi gradually moved closer to the ANC, especially under the leadership of its former president, Thabo Mbeki. Although the political circumstances had changed, Buthelezi continued to use Seme’s name to advance his political interests. The purpose for appropriating Seme’s name however changed. -

Steve Biko, the Politics of Self-Writing and the Apparatus of Reading

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of the Western Cape Research Repository Incomplete Histories: Steve Biko, the Politics of Self-Writing and the Apparatus of Reading Premesh Lalu Abstract This paper gathers together deliberations surrounding Steve Biko’s I Write What I Like as it simultaneously registers the critical importance of the text as an incomplete history. Rather than presupposing the text as a form of biography or following a trend of translating Biko into a prophet of reconciliation, I argue that the text leads us towards the postcolonial problematic of self-writing. That problematic, I argue, names the encounter between self-writing and an apparatus of reading. The paper stages the encounter as a way to make explicit the text’s postcolonial interests and to mark the onset of an incomplete history. This, I argue incidentally, is where the postcolonial critic may set to work to finish the critique of apartheid. Incomplete histories call attention to how that which is unintelligible in a text makes an authoritative reading difficult. How else can one write but of those things which one doesn’t know, or knows badly? It is precisely there that we imagine having something to say. We write only at the frontiers of our knowledge, at the border that separates our knowledge from our ignorance and transforms the one into the other. Only in this manner are we resolved to write…Perhaps writing has a relation to silence altogether more threatening than that which it is supposed to entertain with death.